Medication-Related Hypersomnia

Hypersomnia

Hypersomnia is defined as excessive sleepiness out of proportion for age, gender and development in any given individual. Features that may be used to describe hypersomnia include persistent sleepiness, sleep episodes that may be resistible, non-refreshing and long-lasting periods of sleep without associated sleep-onset REM periods which characterize narcolepsy. The excessive sleepiness may be associated with increased sleep time, even sleep drunkenness, or difficulty waking. That hypersomnia is a significant finding is underscored by the International Classification of Sleep Wake Disorders manual (ICSD-2), which includes a section specifically related to hypersomnia disorders which are not in context with sleep-related breathing disorders. Among the well-described categories are narcolepsy with and without cataplexy, recurrent hypersomnia and idiopathic hypersomnia.1 Sleepiness is children and adolescents is more commonly related to a multitude of factors (imposed academic, social or work-related schedules), actual sleep disorders, such as behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome, poor sleep hygiene, sleep-related breathing disorder, restless legs syndrome, or even circadian rhythm disorder, rather than a disorder of sleepiness itself.2 As such, disorders of sleepiness have been increasingly recognized by clinicians around the world, particularly over the past decade. What makes hypersomnia challenging to recognize is that children may not present clinically as adults do, and often the hypersomnia becomes a concern only when it interferes with academic performance or societal expectations of the child, adolescent or their caregivers. In addition to defined disorders of hypersomnia, hypersomnia itself can occur due to the ingestion of a drug or substance. Related to the use of medications, hypersomnia may be observed with the abrupt cessation of excessive stimulant use (abuse) or, alternatively, the sleepiness complaint may result from previous long-term use of stimulants with termination of use (chronic use). Hypersomnia may also result from use of sedatives such as benzodiazepines, barbiturates, gamma hydroxybutyrate or alcohol. Other medications that may result in sleepiness include high doses of anticonvulsant medications or even opioid analgesics. Another overlooked category are over-the-counter medications such as sedating antihistamines, or anti-emetics which are often used as sleep aids but also as agents of abuse. In addition, medications used in combination may compound the hypersomnia effects such as the combinations of alcohol mixed with sedatives. Medications used for other medical problems that may cause hypersomnia such as varenicline (Chantix), a smoking cessation medication, or some chemotherapeutic agents will not be discussed. The chapter will discuss some of the available evidence related to these medications and highlight important clinical considerations. The increasing use of medication in general has resulted, predictably, in the unintended uses of said medications, possibly increasing the incidence of sleepiness in children and especially adolescents. Many different medications have associated reports of hypersomnia as an adverse drug event related to their use. The lengthy list of potential culprits will not be reviewed here but the interested reader can search other sources such as drug monographs or drugcite.com.

Sleep–Wake Continuum: Anatomy and Its Substrates

From historical experiments involving the introduction of brain lesions in animals to facilitate the study of sleep and wake behaviors, the field of inquiry has evolved. Findings now suggest that sleep and wake states are generated by specific neurotransmitters in specific neuronal systems which together have widespread projections in the brain. Sleep and waking behavior can occur in the absence of the cortex, but the cortex is involved in coordination with the ascending reticular activating system to maintain arousal and alertness. Sleep regulatory substances (SRS) are considered to occur apart from these mechanisms and felt to be contributing factors to the sleep–wake continuum. It has been found that wakefulness increases SRS production while SRS themselves promote and alter sleep. For a substance or neurotransmitter to be considered a sleep regulatory factor it must meet the following criteria: (1) the substance and/or its receptor oscillates with sleep propensity, (2) sleep is increased or decreased with administration of the substance, (3) blocking the action or inhibiting the production of the substance changes sleep, (4) disease states, e.g., infection, associated with altered sleep also change levels of the putative SRS, and finally (5) the substance acts on known sleep regulatory circuits.3 Medications may exert their effects along various aspects of the same pathway as SRS function to inhibit or enhance sleep. The molecular basis of medications from microinjection studies are well established from various drug classes. What are less well known are the anatomic sites where different medications work to induce sleep. Just as a single EEG measure is insufficient to differentiate sleepiness, various medications uniquely affect the degrees of sleepiness in different populations. As a result of hypersomnia, manifestations of sleepiness may include hyperactivity, motor restlessness, behavioral problems and poor academic performance, particularly in children.

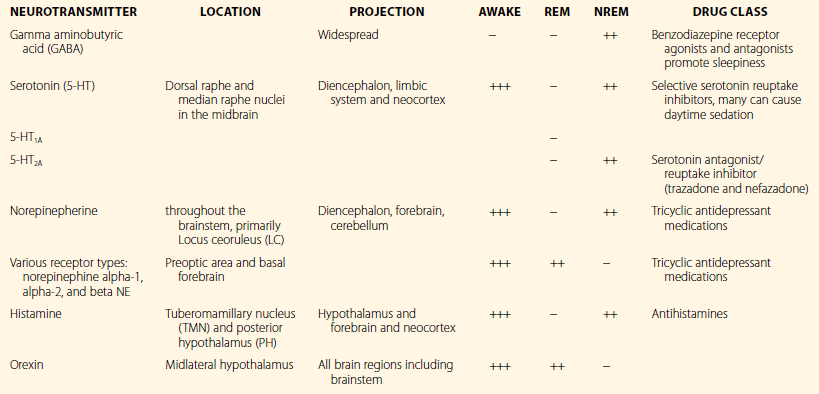

No specific structure of the brain is independently involved in the maintenance of sleep or wake states. Rather, it is unique types of neurons within the same structure which may be playing a role in maintaining the state of sleep or wakefulness. Wakefulness and alertness are maintained by neurons within the brainstem ascending reticular formation that send projections to the thalamocortical pathways via two routes, the dorsal pathway and in the posterior thalamus, and the basal forebrain in the ventral pathway.3,4 Neurons that are involved in activation and wake promotion are concentrated in certain regions of the brain including the oral pontine, midbrain tegmentum and posterior hypothalamus. In contrast, the sleep-promoting regions are in the brainstem, dorsolateral medullary reticular formation, basal forebrain, and anterior hypothalamus ventrolateral preoptic area. Sleep is promoted through the inhibitory neurotransmitters, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GABA) and galanin. Experiments in the 1950s and 1960s showed that acetylcholine is important for vigilance and cortical activation. Locus coeruleus neurons using norepinephrine project diffusely to the forebrain and brainstem to maintain cortical activation. Further studies suggest that norepinephrine and adrenergic receptors are important for stimulating and maintaining activating processes, whereas dopaminergic nuclei in the midbrain ventral tegmental areas are important in stimulating behavioral arousal. The posterior thalamic neurons have histamine, which has been long assumed to play a role in vigilance, and have widespread projections to areas of the hypothalamus and cortex. Orexin (hypocretin) also has widespread projections across the forebrain and cortex is involved in maintaining wakefulness. Serotonergic neurons from the raphe nuclei are also important in maintaining wakefulness. Adenosine is another neurotransmitter involved in sleep–wake regulation in the homeostatic process, and may promote sleep through anticholinergic activity in the basal forebrain and brainstem. There may be many other neuroactive substances such as cytokines that alone or in combination with some of these established neurotransmitters further mediate sleep and wake states. Medications may cause hypersomnia by different mechanisms, by either promoting sleep-activating neurons (GABA), or inhibiting the wake-promoting regions (antihistamines).4 Medications may cause hypersomnia if they impair wakefulness either by the sedating effect lasting longer or prolonged action lasting into waking hours. Medications that promote alertness may impair sleep continuity. Much of the available data on use of these psychoactive medications are from adults, and effects on children may not be the same.5 Table 22.1 provides a simplistic categorization of the neurotransmitter role in sleep and wake determination and primary anatomic location that is involved. Different classes of medications and the associated evidence in children and adolescents are discussed below.

Table 22.1

Neurotransmitters and Neuroanatomic Associations and their Rates of Discharge

(Data from Priniciples and Practice of Sleep Medicine.)

Abuse or Misuse of Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medications

The use of medications has climbed steadily over the years in all fields of medicine, particularly in sleep medicine, either to promote wakefulness or sleepiness, depending on the presenting problem. As a result of this, our collective desire to manipulate and regulate sleep–wake cycles as much as we dictate personal schedules is rampant across society, and children are no exception, either because of parental or societal expectations or their own in meeting all their social and personal demands. Strategic and direct marketing to consumers and prescribers has contributed to the widespread use of pharmacological agents to manipulate and treat sleep. Compounding this problem is that medications are no longer available just to those with prescribing authority. Internet access has enhanced the spread of drug information as well as the distribution of medications themselves, fuelling the phenomenon. One could also surmise that the current cultural ideation of a ‘magic pill’ or cure-all for any ailment has resulted in the development of a focused pharmaceutical industry promoting medications for actual or perceived medical conditions. According to the FDA, from 1960 to 2004, the amount spent on prescription drugs increased from $2.7 billion to over $200 billion with no expected reduction, as more sophisticated medications are developed for targeted use.6 Most importantly, the misperception, particularly in adolescents, that medications prescribed by physicians and dispensed by pharmacists are safer than illicit drugs has resulted in a widespread epidemic of misuse of prescription and over-the-counter medications.7

Society’s ever-increasing use of medications has resulted in the intentional abuse of prescribed and over-the-counter (OTC) medications to affect mood, performance, and sleep–wake state. A wide variety of classes of medications contain the potential for abuse including: sedatives, opioids and derivatives, stimulants, tranquilizers and muscle relaxants, as well as centrally acting agents. Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in 2010 showed that almost one-third of individuals over age 12 who used drugs for the first time in 2009 had begun by using a prescription drug non-medically.8 Data also showed that prescription drugs account for the second most commonly abused category of drugs after marijuana but ahead of cocaine, heroin and methamphetamines.9 The National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed in 2010, about 22.6 million Americans aged 12 and older had used illicit drugs during the past month, including prescription-type psychotherapeutics non-medically.8 When lifetime prevalence of misuse of medications is considered, the number is a staggering 52 million individuals aged 12 and older, representing 20.6% of the US population.10 The majority of these medications are obtained from friends or relatives (55%), and 17.3% from physicians, 4.4% from strangers; 0.4% reported buying the drug on the internet. Non-medicinal use of psychotherapeutics occurred in 7.0 million (2.7%) children 12 and older compared to 6.3 million in 2002.9 The types of medications used non-medicinally were: pain relievers (5.1 million), tranquilizers (2.2 million), stimulants (1.1 million), and sedatives/hypnotics (374,000). The rates of use of these medications do vary by age, with increasing prevalence of use with age (4.0% in children age 12–13 years, to 9.3% in those age 14–15 years, to 16.6% in 16–17-year-olds).9 These data suggest that use of psychoactive medications for non-medicinal purposes is common among youth. For the clinician, the challenge lies in trying to differentiate not only what the complaint of hypersomnia is as a result of the complex interplay of development, socio-cultural influence on sleep–wake regulation and a possible sleep disorder, but also being able to differentiate iatrogenic causes of sleepiness that may further compound the presenting complaint. For example, the multiple sleep latency test may be positive, not because of the true hypersomnia or associated disorder, but rather the use of the medications that are used in combination with the given youth’s circadian rhythm that may be influencing the findings. Conversely, use of stimulant medication or caffeine, either in the form of energy drinks or excessive use of other forms of caffeine, as a countermeasure may mask the true sleepiness that is present for the given adolescent. For patients on anticonvulsant medications, either as a mood stabilizer or for their epilepsy, teasing apart the true sleepiness versus the sleepiness resulting from medications or even psychiatric disorder can be quite challenging.

With increasingly rapid advances in technology, access to medical services and information has also advanced. Previously, prescriptions or medications were either prescribed or bought directly from a pharmacy. Presently, any individual with access to the internet may order a variety of prescription and over-the-counter medications, delivered straight to their home. Many sites that sell medications on the internet may or may not require a prescription, or have opportunities for individuals to gain inappropriate access to these medications. The lack of regulation also does not guarantee that the consumer is getting appropriate or the actual medication that is prescribed. There were over 340 online ‘approved pharmacies’ in 2010 and many rogue pharmacies (FDA website).11 Increased travel to countries where access to prescription medications is less diligently controlled also increases the individual’s chances of obtaining potentially harmful medications. The widespread availability of these agents not only improves access to, but provides more opportunities for those who are prone to abuse the medications, to obtain them or seek out these agents as substitutes when the drug of choice is not available.

A particular abuse of medications in adolescents, referred to as ‘pharming,’ warrants special consideration, particularly as the prescription and over-the-counter medication abuse of cough and cold preparations is becoming more common. Factors that promote the likelihood of abuse include the ease of accessibility, since most of these medications are widely available in homes, are relatively inexpensive, and decreased perception of potential harm because they are legal.12 The abuse of these drugs is strongly associated with abuse of alcohol and other illicit substances.13 Data from a self-administered study of 7300 adolescents from grade 7–12 revealed that one in five (19%) of 4.5 million reported abusing prescription medications to ‘get high’ while one in ten (10% or 2.4 million) reported abusing cough medications to ‘get high.’ These findings exceed rates of abuse from illicit substances such as methamphetamines (8%).13 In addition, a nationwide survey among 50 000 students from grade 8 revealed a higher use of narcotic pain relievers than previous years in grades 8 and 10.14 Data from the California Poison Control Center showed dexomethorphan abuse increased 10-fold from 1999 to 2004, with a 15-fold increase in adolescents aged 9–17 years.15 Many adolescents obtain these medications from their peers16 or from their social network of friends, relatives, physicians.17 These medications may be used as sleep aids or study aids. There is also less social stigma for use of these medications rather than street drugs.13 Prescription medications abused by adolescents including opioid analgesic agents, sedative hypnotics and stimulants are discussed below.