Malrotation and Volvulus

John J. Aiken

Malrotation is a term used to describe a spectrum of anatomic abnormalities resulting from incomplete rotation and fixation of the intestine during early fetal development. Variants include incomplete, nonrotation, or reversed rotation. Midgut volvulus is a devastating consequence of the lack of bowel fixation that results in ischemic infarction of much of the small and large intestine, with short gut syndrome ensuing if volvulus is not recognized and treated emergently.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Malrotation is reported to occur with a frequency of 1 in 3500 to 6000 live births, although the actual incidence of malrotation is unknown because many rotational anomalies remain asymptomatic throughout life and are therefore undiagnosed.1 Either sex can be affected, with the anomaly slightly more common in boys.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

As described in Chapter 381, the midgut normally herniates out of the peritoneal cavity into the umbilical stalk at about week 5 of development in the human fetus. As the intestine returns to the abdominal cavity between the 10th and 12th week of gestation, a process of rotation turns it around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery and fixation of the intestine occurs, culminating with localization of the duodenojejunal junction (ligament of Treitz) in the left upper abdomen and the cecum in the right lower quadrant in the full-term infant (see eFig. 381.5  ). This results in the oblique broad-based fixation of the mesentery to the posterior abdominal wall that prevents volvulus from occurring. The various forms of malrotation result from aberrant rotation and fixation of the bowel, as well as associated abnormal mesenteric bands that may obstruct the bowel (Ladd bands).

). This results in the oblique broad-based fixation of the mesentery to the posterior abdominal wall that prevents volvulus from occurring. The various forms of malrotation result from aberrant rotation and fixation of the bowel, as well as associated abnormal mesenteric bands that may obstruct the bowel (Ladd bands).

In nonrotation or incomplete rotation, the most common form of malrotation, the cecum typically resides in the upper abdomen just to the left of midline, and the duodenaljejunal segment lies anteriorly and just to the right of midline; fixation of the mesentery is absent. This anatomic derangement allows axial rotation of the midgut around the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in midgut volvulus with the potential for intestinal obstruction, ischemia, and necrosis.

Mixed rotational anomalies are a less common and highly variable group of anomalies in which the rotational process is arrested or disrupted, causing a spectrum of anatomic variations. Mesocolic (paraduodenal) hernias are a rare group of malformations that result from failure of the normal fixation of either the right or left mesocolon to the posterior body wall. The resulting spaces create the potential for intestinal obstruction due to sequestration and entrapment of the small intestine between the mesocolon and the posterior body wall.

Rare cases of familial malrotation suggest a genetic link in some cases.2

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

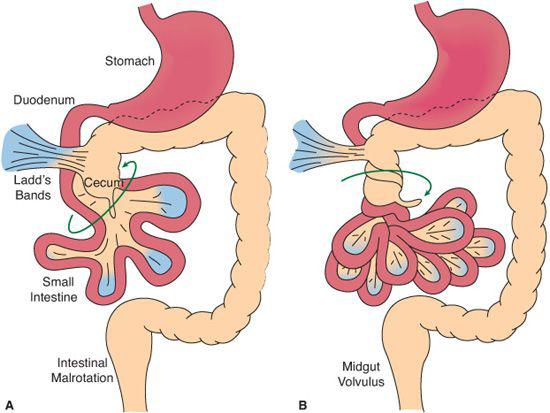

The clinical consequences of malrotation vary depending upon the length of the superior mesenteric artery pedicle and the fixation of the bowel.3 Volvulus is the most ominous and concerning presentation due to the resultant ischemia and bowel necrosis. It occurs as the bowel twists on its axis, strangling the mesenteric base (Fig. 397-1). Malrotation may also present with obstruction due to kinking of the abnormally positioned duodenum; duodenal obstruction from extrinsic compression by peritoneal bands (Ladd’s bands) that extend across the duodenum as they course from the right upper abdomen to the abnormally located cecum; and associated intrinsic duodenal atresia, or stenosis. Midgut volvulus can occur antenatally and result in proximal jejunal atresia and congenital short gut syndrome.

Malrotation may occur as an isolated abnormality, but about half of the patients with malrotation have other associated congenital anomalies, including gastrointestinal (duodenal and/or intestinal atresias), central nervous system, cardiac, respiratory, and genitourinary systems abnormalities.4 All patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), omphalocele, and gastroschisis have malrotation. In addition, pyloric stenosis, Meckel diverticulum, Hirschsprung disease, imperforate anus, esophageal atresia, biliary atresia and abnormalities of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tree, prune belly, megacystis-microcolon syndrome, situs inversus, and the aspleniapolysplenia congenital heart malformation syndrome have been described in association with malrotation.5

Patterns of clinical presentation include midgut volvulus, partial duodenal obstruction, and occasionally, chronic abdominal complaints. The onset of symptoms can be acute, intermittent, or recurrent, and the manner of presentation tends to be age dependent. The classic and most common presentation of malrotation is with gastrointestinal obstruction characterized by bilious emesis (see Chapter 389), but not all patients present with bilious emesis.6

FIGURE 397-1. A: Ladd’s bands fix the cecum near the narrow mesenteric pedicle. B: Rotation around this axis results in volvulus.

The majority (75%) of cases of malrotation with volvulus occur in the first week to month of life, and approximately 90% of cases occur prior to 1 year of age. Physical findings in infants with volvulus are variable and unreliable. The infant may be irritable, with a soft abdomen, until the intestinal ischemia leads to bowel necrosis, peritonitis, third-spacing of fluid, and signs and symptoms of septic shock. Hematemesis, melena, and anemia may result from intestinal mucosal ischemia. Midgut volvulus may be incomplete or intermittent. Typically, patients are older and have chronic nonspecific symptoms of abdominal pain, intermittent episodes of emesis (which may be nonbilious), early satiety, weight loss, failure to thrive, or malabsorption and diarrhea. With partial volvulus, the resultant mesenteric venous and lymphatic obstruction may cause chylous ascites or impair nutrient absorption and produce protein loss into the gut lumen. Melena, guaiac-positive, or grossly bloody stools may result from mucosal ischemia and may lead to anemia.

Duodenal obstruction may also occur with malrotation from kinking of the abnormally positioned and tortuous duodenum, from intermittent volvulus causing duodenal obstruction from torsion, or from extrinsic obstruction from Ladd bands. Intrinsic duodenal obstruction from atresia or stenosis must also be considered. Signs and symptoms are similar and are typical of any high intestinal obstruction. They include bilious emesis, abdominal pain, or both. Physical findings may be similar to those patients with volvulus, but the presentation is typically less acute than in midgut volvulus; thus, patients may have persistent abdominal distension, vomiting with dehydration and hypochloremic, hypokalemic, and metabolic alkalosis from vomiting. Plain abdominal radiographs are variable and may demonstrate findings suggestive of proximal intestinal obstruction (dilated proximal intestine and stomach with little distal gas) or may be nonspecific and unremarkable because proximal intestinal obstructions may be decompressed by vomiting.

Chronic nonspecific abdominal complaints may also be due to malrotation. This mode of presentation is more common in older patients. Symptoms include chronic abdominal pain, chronic pancreatitis, weight loss, failure to thrive, early satiety, intermittent diarrhea or blood by rectum and are due to chronic partial duodenal obstruction or intermittent volvulus. Presumably, symptoms result from intestinal obstruction or from intermittent occlusion of the mesenteric venous or lymphatic systems, causing edema of the bowel wall, mesentery, and mesenteric lymph nodes. Chronic arterial insufficiency caused by a partial volvulus may result in diarrhea, chronic abdominal pain, worsening pain after meals (intestinal angina), or melena as a result of intestinal mucosal ischemia.

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

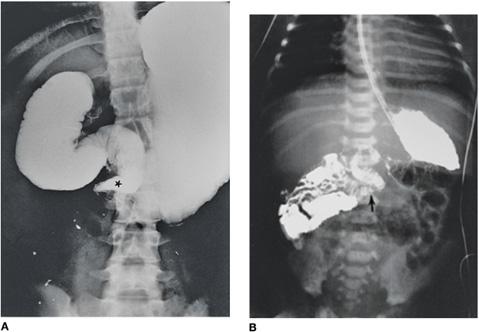

If an infant or child presents with signs of intestinal obstruction, initial diagnostic testing should not be prioritized over physiologic stabilization, which occurs concurrent with the diagnostic evaluation. Initial evaluation begins with a plain abdominal radiograph that most often demonstrates a proximal bowel obstruction with a distended stomach and proximal duodenum. Usually, there is a paucity of air in the distal small bowel, but multiple, dilated loops of bowel with air/fluid levels are also seen in malrotation with volvulus. The most worrisome radiograph demonstrates a relatively “gasless” abdomen secondary to sequestration of fluid into the bowel and abdominal cavity portending significant intestinal ischemia or necrosis. Physical and plain radiograph findings may be minimal early in presentation. Therefore, in any case of bilious vomiting the diagnosis of malrotation with volvulus should be considered, and an upper GI contrast study should be performed. The classic contrast study shows a complete obstruction in the second or third portion of the duodenum, with a tapering, funnel appearance from the proximal dilated duodenum to the point of obstruction that is reminiscent of a bird’s beak in appearance. Partial obstruction of the duodenum shows a spiral or corkscrew (coiled spring) appearance of the duodenum, with the proximal small bowel to the right of midline (Fig. 397-2A).

In patients with malrotation but without volvulus, the diagnosis of malrotation is made based on the position of the duodenaljejunal junction (ligament of Treitz) (see Fig. 397-2B). The normal position of the duodenaljejunal junction is to the left of the spine at the level of the gastric antrum, fixed tightly to the posterior body wall. In patients with malrotation, the duodenaljejunal junction is typically found on the right side of the spine, inferior to the duodenal bulb, and more anterior than expected. The lateral view is very useful in assessing the anterior and posterior relations of the duodenaljejunal junction. In addition, often all of the loops of the proximal jejunum are found on the right side of the abdomen. Contrast enema (barium or water-soluble contrast) is often the initial study used in evaluating infants with more general concerns of neonatal intestinal obstruction, and this study may suggest malrotation when there is an abnormal position of the colon, with the entire colon on the left side of the abdomen and the cecum in the upper abdomen either midline or just to the left of midline. This finding is suggestive but not definitive for malrotation because a high-riding or mobile cecum is found in up to 15% of normal infants. In addition, duodenal obstruction caused by malrotation may occur in the presence of a normally positioned cecum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree