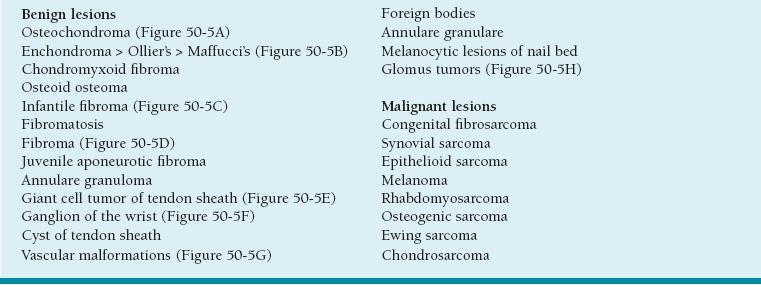

FIGURE 50-1 Photograph of dorsal hand mass centered between ring and small finger metacarpals.

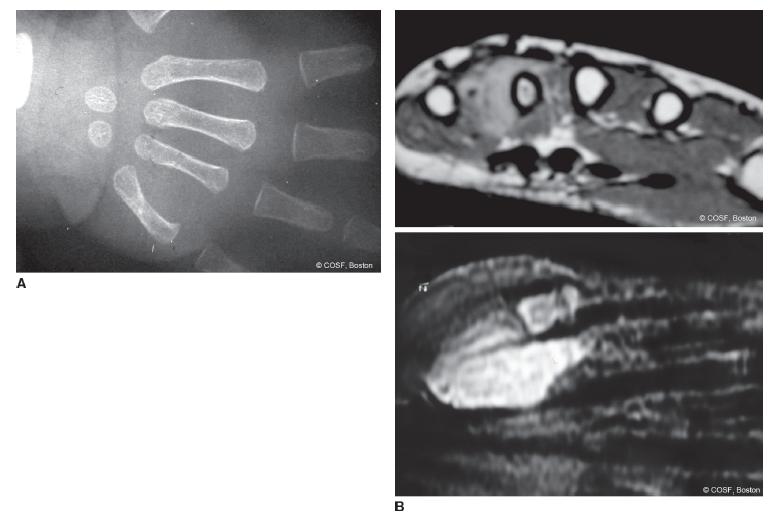

FIGURE 50-2 A: Radiograph revealing soft tissue mass effect on ring metacarpal. Unfortunately, this was initially interpreted as fracture callus. B: MRI scans of lesion confirming malignancy.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

- What are the common tumors of the pediatric upper limb?

- What differentiates a benign from a malignant tumor on physical exam and radiologic evaluation?

- What are the indications for CT scan, MRI scan, bone scan, and ultrasound in a diagnostic workup of a suspected tumor of the hand and upper limb?

- When is biopsy alone the appropriate first surgical treatment?

- When is excisional biopsy the preferred treatment?

- What are the indications for terminal segment resection versus ray resection?

- When is limb salvage an appropriate surgical treatment?

- What are the surgical options for limb salvage?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Etiology and Epidemiology

It’s not the disability that defines you, it’s how you deal with the challenges the disability presents you with. We have an obligation to the abilities we DO have, not the disability.

—Jim Abbott

Soft tissue and bony masses of the hand and upper limb in children almost always raise serious concerns among parents and primary caregivers about malignant potential. Fortunately, malignancies of the hand are exceedingly rare in children and uncommon in the upper limb. Benign lesions predominate, but malignancies do occur. Differentiation between benign and malignant lesions requires careful attention to detail on physical exam, radiologic evaluation and interpretation, and surgical decision making. It is necessary to keep a high awareness of the very real possibility of malignancy when assessing all palpable masses and radiographic lesions (Figure 50-3). Inappropriate reassurance can be disastrous for one and all.

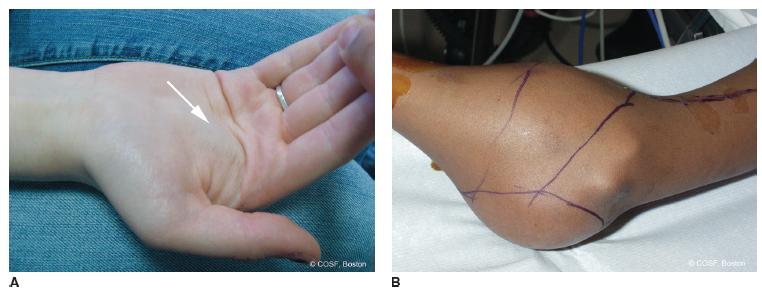

FIGURE 50-3 A: Accessory lumbrical muscle presenting as a mass in the palm, a worrisome anatomic area for possible malignancy. B: A very late presentation for a massive lesion about the elbow of obvious concern for malignancy. This case was a synovial sarcoma.

Common primary malignancies of bone include osteogenic sarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. Chemotherapeutic advances improved 5-year survival significantly and led to limb salvage rather than amputation as the orthopaedic surgery treatment of choice in most tertiary medical centers.1,2 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can lessen the surgical resection and improve limb salvage options. A positive response to preoperative chemotherapy is a clear positive prognostic factor.3 Metastatic and recurrent disease have a poor prognosis. Thoracotomies and tumor resection of pulmonary metastases can improve survival.

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare in children and adolescents. Infantile fibrosarcoma is the most common sarcoma in children <1 year of age but represents <1% of all childhood cancers. Survival of infantile fibrosarcoma with a combination of surgery and chemotherapy is better than adolescent or adult fibrosarcomas.4,5 Rhabdomyosarcoma (embryonal is the most frequent type in children, but alveolar type occurs most often in limbs), primary neuroectodermal tumors, synovial sarcoma, and neurofibrosarcomas are the most common of the rare soft tissue sarcomas in children and adolescents.6,7 Radiation therapy is frequently used in the treatment for pediatric and adolescent sarcomas, particularly in cases of limited marginal resections.8 Long-term consequences of the radiation therapy in survivors include poor bony growth, pathologic fracture, and secondary malignancy.9,10 Defining the biologic behavior of a pediatric sarcoma includes the his-tologic response to chemotherapy and chromosomal analysis for specific translocations and resultant fusion genes.11

Clinical Evaluation

In general but not always, lesions of bone and soft tissues play by the following rules: (1) benign soft tissue lesions are well circumscribed, often encapsulated, grow slowly, and do not metastasize and (2) malignant lesions are expansile, have poorly defined borders, grow rapidly, and can spread to other anatomic sites. Size is not a reliable diagnostic discriminator (i.e., ganglions can be gigantic; malignancies can be barely palpable), nor are symptoms always helpful (not every malignancy hurts in the nighttime; some benign lesions are very painful). Thus, physical exam is useful but not perfectly precise in distinguishing benign from malignant lesions.

In the evaluation of an upper limb mass in a child, fractures, infections, and their sequelae are important parts of the differential diagnosis. So too are metabolic bone disease, systemic disorders, and inflammatory processes. Laboratory testing with complete blood count and differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, serum calcium, phosphate, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, and Lyme titers is commonly indicated to help discriminate among diagnoses.

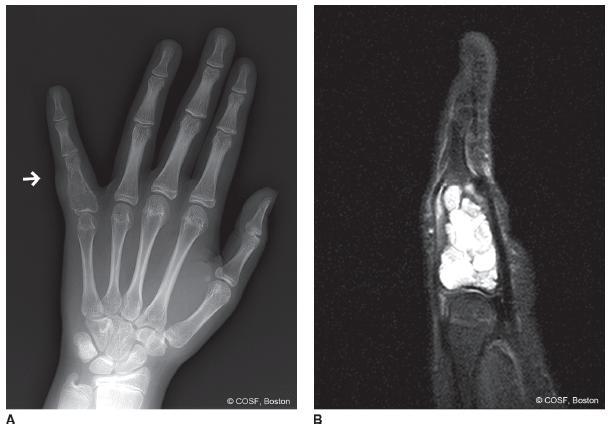

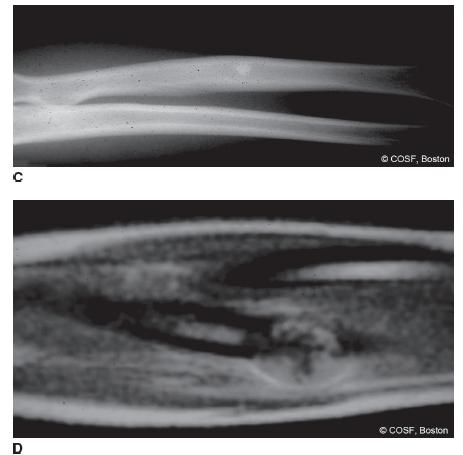

Musculoskeletal imaging is critical. Short of biopsy and histologic exam, imaging can usually differentiate benign from malignant lesions and lead to an accurate diagnosis. Plain radiographs provide excellent anatomic information about the degree and type of bony involvement (Figure 50-4A). All concerning soft tissue and musculoskeletal lesions should have at least two perpendicular plain radiographs to define size, what the lesion is doing to the bone, how the bone is reacting to the lesion, and if there is soft tissue involvement. High-resolution ultrasounds are relatively inexpensive and easy compared to computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Ultrasounds can distinguish cystic from solid lesions, and, in some cases (e.g., unclear ganglion), this may be all that is necessary. CT scans allow visualization of intramedullary canal, cortical and soft tissue involvement, and usually provide an accurate diagnosis of the lesion. MRI scans better define soft tissue extension and intramedullary skip lesions (Figure 50-4B). These scans are used not only for diagnosis but also for staging and surgical resection decisions.12

FIGURE 50-4 A: Expansile lesion of proximal phalanx consistent with an aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC). B: MRI scan of same lesion with fluid-fluid level consistent with ABC. C: Plain radiograph of forearm with sclerosis and periosteal reaction of diaphyseal radius. D: MRI scan revealing primary bone malignancy, which by biopsy was Ewing sarcoma.

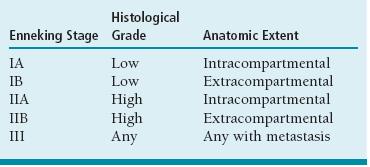

If the diagnosis is still unclear or worrisome for malignancy, biopsy is indicated. The biopsy incision needs to be judiciously created so as not to jeopardize later limb salvage or segmental resection options. Consultation with, or transfer of care to, an orthopaedic oncologist is often appropriate and wise. Surgical staging is now standardized (grades I to II) by Enneking criteria13 (Table 50.1) for grade low (G1), high (G2), regional or distant metastases (M), and compartment involvement (intra- [T1] or extra[T2]). In the end, the pediatric hand and upper limb surgeon needs to be aware of and provide appropriate care and consultation for, among others, any of the lesions noted in Table 50.2. Depending on your situation, your oncology practice may be limited to diagnosis, workup, and referral to the appropriate subspecialist, or you may participate in surgical care and patient management. For us, upper limb and hand malignancies are managed using a team approach, with our surgical expertise being utilized for the surgical access and complex reconstructions. Benign lesions often receive complete care by us.

Table 50.1 Modification of Enneking criteria

Adapted from Enneking W F. Staging of musculoskeletal neoplasms. In: Uhthoff UK SE, ed. Current Concepts of Diagnosis and Treatment of Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 1984:1–21.

FIGURE 50-5 Various benign masses of the hand that need to be distinguished from malignant masses. A: Large distal ulna osteochondroma in a 2 year old. B: Multiple enchondromas from Ollier disease. C: Infantile fibroma. D: Fibroma of the hypothenar eminence. E: Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath. F: Ganglion of the wrist G: Vascular malformation of the wrist preoperatively (G1) and intraoperatively (G2). H: Glomus tumor of nail bed prior to and during excision.

Surgical Indications

Biopsy of potential malignant lesions needs to occur after completion of the medical oncology evaluation and diagnostic laboratory and radiographic workup. The biopsy is performed in conjunction with the surgical pathologist to plan frozen section microscopy (often with pathologist, oncologist, and surgeon reviewing together), permanent histology, and tissue typing studies. Remember to always obtain cultures because infection is a great mimicker. If there is any question about the ability to safely obtain the proper specimen and accurately diagnose the patient’s condition, referral for biopsy is strongly advised.

Timing and planning for surgical reconstruction is done once an unequivocal diagnosis is made. Tumor board conferences aid the entire team, with medical oncologists, radiation therapists, musculoskeletal radiologists and pathologists, and surgical subspecialists discussing each case. Protocols are reviewed; plans and timing for chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery are made.

Biopsy

Biopsy

In the 8th inning you can’t hear the roar of the 9th, all you can do to hold yourself together, and trust.

—Jim Abbott

Planning the biopsy incision is critical. Poorly planned or executed incisions can prevent limb salvage due to compartment contamination of malignant cells. The name of the game is to avoid surprises. Needle biopsies are rarely performed in the upper limb and hand. Open biopsies are the norm. Longitudinal incisions that can be excised completely with definitive tumor resection and reconstruction are mandatory. Biopsies need to be performed under tourniquet control but not with compressive exsanguination, as this will spread tumor cells. Elevation of the limb for a few minutes before tourniquet inflation is recommended. Dissection to the tumor is done within the compartment of the tumor, so later en bloc resection of the entire biopsy path from skin to lesion can be performed. Dissection through muscle rather than with muscle elevation or retraction reduces contamination. Multiple specimens are obtained for frozen section biopsy. Microscopic sampling and preliminary analysis while the patient is still under anesthesia will determine the adequacy of the specimens obtained for diagnosis and special tissue typing. Frozen section microscopy does not determine final diagnosis but usually does distinguish malignant from benign. Most biopsies for malignancy are incisional biopsies, with planned definitive excision and reconstruction occurring later after all the information gathering, subspecialty consultation, and family discussions are complete. Excisional biopsy is performed for benign lesions. Excisional biopsies can be intralesional (curettage of enchondroma) (Figure 50-6) or marginal (fibromatosis). Wide excision is required for all malignancies and may include vital structures (nerves, tendons, bones, joints, arteries) that need complex reconstruction. Prereconstruction chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy can often shrink the size of the lesion, allowing for less radical wide margins and more potential for functional limb salvage rather than amputation. Ultimately, preservation of life always trumps preservation of limb, but if you and your team of experts can get both, the more satisfying is the work you do.

FIGURE 50-6 Ollier disease with multiple enchondromas and pain from recurrent pathologic fractures treated with curettage and bone grafting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree