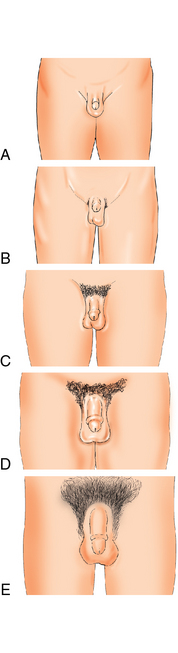

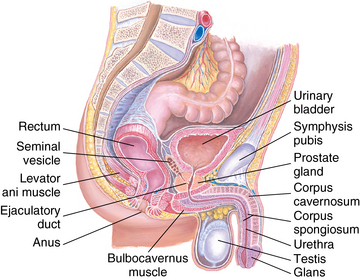

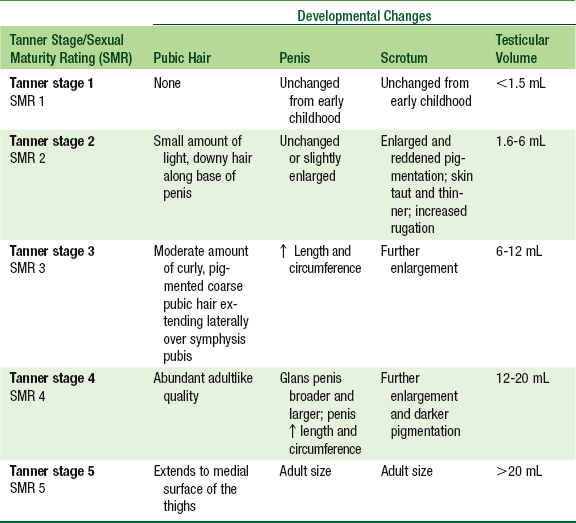

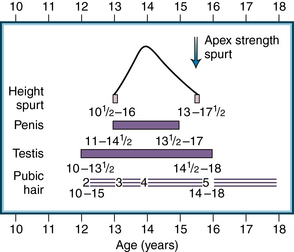

CHAPTER 15 The differentiation of the sexual organs begins as early as the third week of embryonic development, dictated by the sex chromosomes at the time of fertilization.1 The mesoderm is the embryonic layer that becomes smooth and striated muscle tissue, connective tissue, blood vessels, bone marrow, skeletal tissue, and the reproductive and excretory organs. As proliferation of the embryonic layers continues, maturation of the external genitalia in the fetus is established by the twelfth week.1 The sex-determining region of the Y chromosome (SRY gene) activates the differentiation of the embryonic gonad into a testis, without which the gonad would become an ovary. The antimüllerian hormone (AMH) prevents development of the uterus and fallopian tubes, whereas testosterone stimulates the wolffian ducts to develop into the male reproductive structures, including the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicles. Testosterone is also the precursor to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which stimulates the formation of the male urethra, prostate, and external genitalia.1 Urine production begins between the ninth and twelfth weeks and is excreted into the amniotic cavity through the urethral meatus. During development, the fetus continues the production and excretion of urine, which forms the amniotic fluid. Between the seventeenth and twentieth weeks, the testes, which develop in the abdominal cavity, begin to descend along the inguinal canal into the scrotum, bringing the arteries, veins, lymphatics, and nerves that are encased within the cremaster muscle and spermatic cord.1 The inguinal canal closes after testicular descent. Incomplete or abnormal embryonic development of the inguinal canal predisposes the newborn to the formation of hydroceles or hernias. Preterm infants are at increased risk for these conditions. At birth, the infant’s genitourinary system is functionally immature with limited bladder capacity, inability to concentrate urine sufficiently and frequent voiding. Growth of the fetus and differentiation of the sexual organs can be affected by placental function, the hormonal environment during pregnancy, maternal nutrition, maternal infection, and genetic factors or chromosomal abnormalities. A fetal insult from intrinsic or extrinsic factors during the eighth or ninth week of gestation may lead to major abnormalities of the developing external genitalia. The impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on the development of the endocrine and genitourinary system is reviewed in Chapter 5. The penis consists of the shaft, glans, corona, meatus, and prepuce. The shaft is composed of erectile tissue called corpora cavernosa (two lateral columns) and corpus spongiosum (ventral column). The anterior portion of the corpus spongiosum forms the glans penis, the border or edge of which is called the corona. The urethra is within the corpus spongiosum, and the orifice, or urethral meatus, is the slitlike opening just ventral to the tip of the penis (Figure 15-1). FIGURE 15-1 Internal and external genitalia. (From Seidel HM et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 7, St. Louis, 2011, Mosby.) The prepuce, or foreskin, is the fold of skin at the tip of the penis that covers the glans penis in the uncircumcised male and forms the secondary fold of skin from the urethral meatus to the coronal region of the penis called the frenulum. The skin of the penis is thin, does not contain subcutaneous fat, and is loosely tied to the deeper layer of the dermis and fascia. Often, the skin of the shaft is more darkly pigmented, particularly in children or adolescents with darker pigmentation or darker skin. The skin of the glans penis does not contain hair follicles, but does have small glands and papillae that form in the epithelial cells to produce smegma, the white oily material made up of desquamated epithelial cells trapped under the foreskin, which is normal and often mistaken as pathological2 (Figure 15-2). The foreskin is generally nonretractable at birth, because of adherence of the inner epithelial lining of the foreskin and glans.2,3 Desquamation of the tissue layers continues until the separation of the prepuce and glans penis is complete secondary to intermittent erections and keratinization of the inner epithelium, generally by 5 to 6 years of age. Partial adhesions of the foreskin to the prepuce may produce smegma along the coronal region, which often persists throughout childhood. The scrotum is made up of a thin layer of skin that forms rugae (folds) and contains the testes. The epididymis is the thin palpable structure along the lateral edge of the posterior side of the testes. Sperm production occurs within the seminiferous tubules in the testes, which connect to the epididymis. The vas deferens is the cordlike structure that is continuous with the base of the epididymis and stores sperm. The spermatic cord extends from the testes to the inguinal ring and is felt only on deep palpation of the testicular sac. The right spermatic cord is shorter in some males, which causes the right testis to hang higher than the left. Table 15-1 presents the physiological variations of the male genitalia in the pediatric age-group from infancy to early childhood. TABLE 15-1 Physiological Variations of the Male Genitalia *Data from Thureen PJ, Hall D, Deacon J, Hernandez JA: Assessment and care of the well newborn, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders. Puberty has a gradual onset and although it is marked by a growth spurt, it may be difficult to ascertain when the first changes in the male begin in the transition to secondary sexual characteristics (Figure 15-3). In males, sexual development, or true gonadal activation, begins with an increase in size of the testicles, which is often difficult to determine. Testicular volume should be evaluated and is the most accurate measurement of the progression of puberty in the developing male. In some boys, this begins around 10 years of age and is complete in about 3 years, with the normal range extending to 5 years.4 The sexual maturity rating (SMR) scale, also known as Tanner stages, helps to classify physical pubertal maturation4 (Figure 15-4 and Table 15-2). Genital development and pubic hair may develop at different rates. Ejaculation usually occurs at SMR 3 during the midpoint of sexual development. Fertility is established by SMR 4, although sperm are present in some quantity with ejaculation during SMR 3. TABLE 15-2 Developmental Changes in Puberty Data from Neinstein LS: Handbook of adolescent care, Philadelphia, 2009, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. FIGURE 15-3 Pubertal changes. (From Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys, Arch Dis Child 45:13-23, 1970.) In male adolescents, it is the tempo of growth and maturation that is distinctly different than that in females. At mid-puberty, with rising testosterone concentrations, most of the rapid linear growth occurs. Recent studies have provided evidence of earlier onset puberty in males, particularly in African-Americans.4 The trend is an overall earlier start of puberty but prolonged progression to genital maturity. Understanding and respecting cultural differences is an important part of the role of the health care provider, particularly in relation to the assessment of the genitourinary system. Identifying which family members may be a part of the discussion and/or be present during the examination of the genitalia and how to approach the exam are the first steps in developing a trusting relationship with the family. Parental and family attitudes about sexuality vary widely both within cultures and among cultures. Sexual awakening first occurs in the young child with the discovery of the genitalia as a sensual organ. This initial experience and the parental attitude toward normal fondling and exploration may set the stage for either normal sexual development in a child or a feeling of shamefulness and an attitude in the child that fosters abnormal functioning throughout life. Often, cultural attitudes concerning sexuality and reproduction form the basis of conflict between the parent and young child or maturing adolescent. Mediating this difference between the adolescent and the parent may be the most important and challenging role for the health care provider. Additionally, documentation in the health care record provides opportunity to communicate these attitudes to the next provider to ensure consistent delivery of care. Before the start of the genitourinary exam, the provider should discuss the rationale for performing this exam as well as what to expect during the exam. Anticipatory guidance is of utmost importance for all age groups beyond the infant and young child. Parents of adolescents should be prepared to leave the exam room for the physical examination of the genitalia after bringing up any concerns during the health history. This gives the provider an opportunity to discuss with the adolescent the consent to confidential reproductive health services and the limits to confidentiality, which differ from state to state (see Chapter 4).

Male genitalia

Embryological development

Anatomy and physiology

Penis

Scrotum and testes

Physiological variations

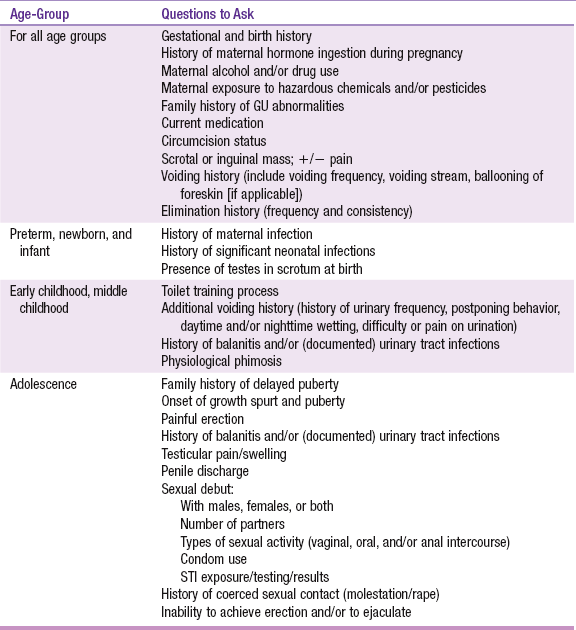

Age-Group

Variation

Preterm infant

Rugae absent on scrotum in low birth weight infant

Testes undescended in ∼20% of infants weighing <2500 g*

Newborn

Rugae present from 37 weeks’ gestation

Note and evaluate any discoloration of scrotum at birth

Testis: volume 1 to 2 ml

Length of penis in term infant: 2.5 to 3.5 cm; size should be palpated during exam

Shaft may appear short or retracted in infants with significant suprapubic fat pad

Infancy/early childhood

Foreskin partially retractable over glans penis

Testes present in scrotal sac

Initial sexual arousal and erection occur with normal sexual exploration or exposure of genitalia

Physiological changes in puberty

Family, cultural, racial, and ethnic considerations

Physical assessment

Preparation

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Male genitalia

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue