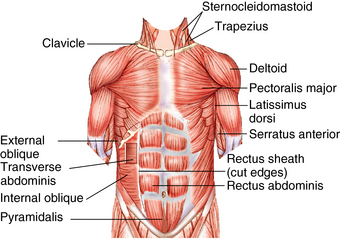

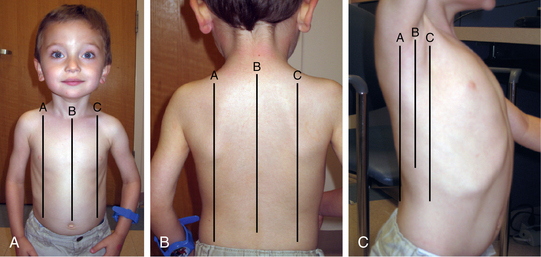

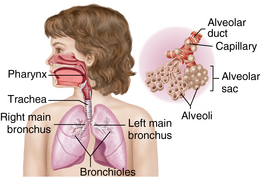

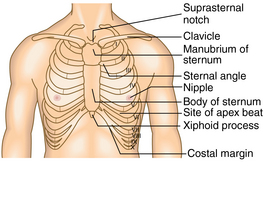

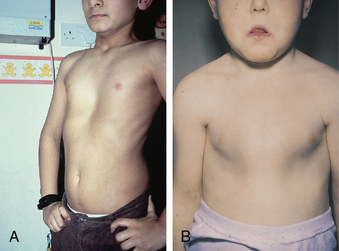

CHAPTER 8 Lung development begins in utero at approximately 4 weeks’ gestation. It occurs in five stages: embryonic, pseudoglandular, canalicular, saccular, and alveolar. During the embryonic phase, the lungs form from a sac on the ventral wall of the alimentary canal. Right and left branches form through budding and dividing. During the pseudoglandular stage, branching of the lung bud occurs, as the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles are formed by 16 to 17 weeks’ gestation. During the canalicular stage, branching of the bronchioles continues and alveoli begin to form. By approximately 25 weeks, the number of bronchial generations with cartilage is the same as the adult lung. Growth of the pulmonary parenchyma and surfactant system occurs during the saccular phase. Maturation and expansion of the alveoli occur during the alveolar period and persist through early childhood.1,2 Breathing movements occur in utero. The movements are irregular, range from 30 to 70 breaths per minute, and become more frequent as gestation progresses. These movements are thought to train the respiratory muscles and promote lung development.2 Fetal gas exchange occurs via the placenta. At birth, the lungs fill with air for the first time and take on the role of ventilation and oxygenation. The fluid in the lungs moves into the tissues surrounding the alveoli and is absorbed into the lymphatic system. At this point, gas exchange occurs via diffusion across the alveolar-pulmonary capillary membranes.1,2 The thorax is the bony cage that surrounds the heart, great vessels, lungs, major airways, and esophagus.3 It is composed of the sternum and ribs (Figure 8-1). The sternum is a flat, narrow bone made up of three parts, the manubrium, the body, and the xiphoid process.4 The manubrium is roughly triangular and attaches to the body of the sternum; the angle at which the manubrium and body meet is termed the manubriosternal angle or the angle of Louis. This angle is in line with the second rib and therefore serves as an important landmark. The xiphoid process is the small, thin, cartilaginous end of the sternum, which varies greatly in shape and prominence in infants and children because of the influence of heredity, intrauterine environment, and nutrition. It sits at the level of T9.4,5 Pectus carinatum, pigeon breast, is the abnormal protrusion of the xiphoid process and sternum, and pectus excavatum, funnel chest, is the abnormal depression of the sternum6,7 (Figure 8-2). The chest cavity is divided, with the middle portion known as the mediastinum. FIGURE 8-1 Anatomy of the rib cage and thorax. (From Revest P: Medical sciences, Edinburgh, 2009, Saunders Ltd.) FIGURE 8-2 A, Pectus excavatum. B, Pectus carinatum. (A, From Chaudry B, Harvey D: Mosby’s color atlas and text of pediatrics and child health, St. Louis, 2001, Mosby. B, From Lissauer T, Clayden G: Illustrated textbook of paediatrics, ed 2, St. Louis, 2001, Mosby.) There are 12 pairs of ribs; the first 7 pairs attach anteriorly via their corresponding costal cartilages to the sternum. Ribs 8, 9, and 10 are attached to the costal cartilage on the rib above them; ribs 11 and 12 do not attach anteriorly and are known as floating ribs. All 12 pairs of ribs attach posteriorly to the thoracic vertebrae. The diaphragm sits at the bottom of the rib cage and is the major muscle of respiration. There are 11 intercostal muscles anteriorly and posteriorly and 8 thoracic muscles, all of which help to increase the volume of the rib cage with inspiration and decrease the thoracic volume with expiration3–5 (Figure 8-3). The following landmarks are often used in describing the location of physical findings of the chest: the midsternal line (MSL), which runs down the middle of the sternum; the midclavicular line (MCL), located on the right and left sides of the chest, runs parallel to the MSL and through the middle of the clavicles (midway between the jugular notch and acromion) bilaterally. Laterally, there are three lines on each side, the anterior axillary line (AAL), the midaxillary line (MAL), and the posterior axillary line (PAL). The AAL begins at the anterior axillary folds, the MAL begins at the middle of the axilla, and the PAL begins at the posterior axillary folds. Posteriorly is the vertebral line that runs down the middle of the spine and the scapular line, which runs down the inferior angle of each scapula4,5 (Figure 8-4). The respiratory system is divided into two parts, the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract. The upper respiratory tract consists of the nasal cavity, pharynx, and larynx and is reviewed in Chapter 13. The lower respiratory tract consists of the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveolar ducts and sacs, and alveoli (Figure 8-5). The trachea is a tube that lies anterior to the esophagus. The distal end of the trachea splits into the right and left mainstem/primary bronchi. This bifurcation occurs at the level of T3 during infancy and childhood. By the time the child is an adult, this bifurcation occurs at T4 or T5. The right mainstem bronchus is shorter and more vertical than the left and, therefore, more susceptible to aspiration of foreign bodies in the young child. Beyond the bifurcation, the bronchi continue to branch into lobar/secondary bronchi. There are three branches on the right and two on the left; each branch supplies one of the lung lobes. These branches further divide into segmental/tertiary smaller bronchi to supply each segment of the lungs and finally the terminal bronchioles. Ultimately, the respiratory tract terminates with the alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs, and alveoli where gas exchange takes place. The bronchial arteries branch from the aorta and supply blood to the lung parenchyma. The blood supply is returned primarily by the pulmonary veins.1,3,5 The lungs are positioned in the lateral aspects of the thorax, separated by the heart and the mediastinal structures. The right lung has three lobes (upper, middle, and lower), and the left lung has two lobes (upper and lower). The apex is the top portion of the upper lobes, which extends above the clavicles. On the right side, the minor or horizontal fissure, located at the fourth rib, divides the right upper lobe (RUL) from the right middle lobe (RML). On the left side, there is a tongue-shaped projection that extends from the left upper lobe (LUL), called the lingula. Laterally, the right lower lobe (RLL) and the left lower lobe (LLL) occupy most of the lower lateral chest area. Only a small portion of the RML extends to the midaxillary line, and it does not go beyond that point. Posteriorly, the vertebral column helps in identifying the underlying lung lobes. T4 marks the inferior portion of the upper lobes and the superior portion of the lower lobes. The base is the bottom portion of the lower lobes and is marked by T10 or T12 depending on the phase of respiration.4 The principle function of the lungs is gas exchange between the atmosphere and the blood. Oxygen is carried into the lungs and carbon dioxide is eliminated. The lungs play a significant role in acid-base balance. Table 8-1 presents variations in growth and development that impact the function of the respiratory system in the infant and young child. TABLE 8-1 Physiological Variations of the Chest and Lungs Complete and accurate information gathering is essential when assessing an infant, child, or adolescent with respiratory symptoms (see the Information Gathering table). Questions should be open-ended and age-specific to allow the parent or caregiver the opportunity to give a full explanation of past and present concerns. In addition, always obtain information directly from the older child or adolescent when possible. Table 8-2 presents a symptom-focused assessment of respiratory conditions for children and adolescents. TABLE 8-2 Symptom-Focused Assessment of Respiratory Conditions Information Gathering for Chest and Lung Assessment at Key Developmental Stages When auscultating breath sounds, use the diaphragm of the stethoscope. The size of the stethoscope being used is extremely important when evaluating respiratory sounds. Stethoscopes with a smaller diaphragm should be used on infants and toddlers. Isolating cardiac and respiratory sounds is difficult in small children with too large a diaphragm, and using a diaphragm that is too small on adolescents or on children who are overweight or obese causes practitioners to miss findings of cardiac and respiratory sounds on auscultation.

Chest and respiratory system

Embryological development

Anatomy and physiology

Thorax

Lower respiratory tract

Lungs

Physiological variations

Age-Group

Physiological Variation

Preterm infant

Respiratory muscles are weak, poorly adapted for extrauterine life; periodic breathing occurs that is similar to fetal breathing; preterm infants become easily hypoxic and apnea occurs

Newborn

Diaphragm is flatter, more compliant; paradoxical breathing occurs in the neonate with inward movement of chest during inspiration; predominantly nose breathers until 4 weeks of age; chest circumference very close in size to head circumference at birth

Infancy

Smaller airways with increased resistance to airflow; rapid respiratory rate; minimal nasal mucus causes mild to moderate upper airway obstruction

Early childhood (1 year to 4 years of age)

Rapid growth and maturation of alveoli improve ventilation; respiratory rate decreases dramatically from newborn period

Middle childhood (5 years to 10 years of age)

Alveoli continue to increase in number; lung development is complete by 5-6 years of age

Adolescence

Alveolar size matures to adult capacity

System-specific history

Symptom

Questions to Ask

Cough

History: Onset of cough symptoms? Was onset sudden or gradual? Coughing for how long? Is cough worsening or changing character? Is cough wet, dry, hacking, barking, whooping? Worse during day or at night? Worse with feeding, sleeping, running? Any other symptoms: Shortness of breath, chest pain/tightness, or wheeze? Choking episodes? History of aspiration (small toy, food, etc.)? Rhinorrhea or nasal congestion? In older child/adolescent: Is cough productive with sputum or nonproductive?

Pattern: Occasional, persistent, or coughing spasms?

Wheeze

History: Onset of wheezing? Was onset sudden or gradually worsening? Any other symptoms: Cough? Shortness of breath? Chest pain/tightness? History of aspiration (small toy, food, etc.)?

Pattern: Occasional, increase with exercise?

Shortness of breath

History: Onset of shortness of breath? Was onset sudden or gradual? Does it occur with activity or rest? Is it difficult to get air in, out, both? History of aspiration (small toy, food, etc.)? Accompanying symptoms of cough, wheezing? History of breath-holding spells, seizures?

Chest pain

History: Onset of chest pain? Was onset sudden or gradual? Is it difficult to get air in, out, or both? Chest pain occurs with movement or rest? Type of pain (sharp, dull)? Ask verbal child to point to area of pain. History of trauma or recent sports injury or weight lifting? Any other symptoms: Cough, wheezing, shortness of breath?

Pattern: Occasional with respirations or persistent?

Age-Group

Questions to Ask

Preterm infant

How many weeks’ gestation? Admitted to newborn intensive care unit? Length of stay? Any episodes of apnea or tachypnea? Need for oxygen? Need for ventilation? For how long? Infant discharged to home on a ventilator/on oxygen? Infant discharged home on any medications? Any maternal substance abuse?

Newborn

How many weeks’ gestation? Birth weight? Any birth complications? Meconium aspiration? Breathing problems at birth? Any episodes of apnea or tachypnea?

Infancy

History of respiratory infections as infant (respiratory syncytial virus [RSV], rhinovirus, etc.)? Frequent upper respiratory infections (URIs)? History of wheezing? Hospitalizations? History of intubations? History of eczema/skin allergy? In daycare? Immunization status? Frequent vomiting after feeds/“choking” episodes? Arches back after feeding?

Early childhood

History of apnea/breath-holding spells? Does child’s speech have a nasal or congested sound? History of nasal congestion, chronic URIs, allergy symptoms, tonsillitis, frequent ear infections? In daycare or preschool? Does child frequently put objects in mouth/nose? Exposure to group A streptococcal infection? Does child snore at night? Exposure to ill contacts? Foreign travel/recent immigrant?

Middle childhood

History of nasal congestion, chronic rhinorrhea, sinusitis, tonsillitis, chronic URIs, recurrent pneumonia? Does child snore at night? Exposure to group A streptococcal infection? History of asthma? Exposure to ill contacts? Foreign travel or recent immigrant?

Adolescence

History of chronic URIs, allergic rhinitis/asthma, recurrent tonsillitis? History of oral sex? Tobacco use? How many cigarettes per day? Marijuana use? Any oral piercings?

Environmental risks

Year home was built? Location (inner city, suburb, rural, near highway/high traffic areas)? Is there a basement? Number of people in home? Anyone smoke in home? Pets in home? Type of heating system? Wood burning stove? Humidifier? Mold? Carpets? Drapes? Mice or roaches? Presence of chemicals/fumes in home or near home?

Physical assessment

Equipment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chest and respiratory system

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue