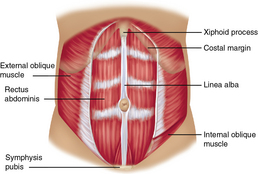

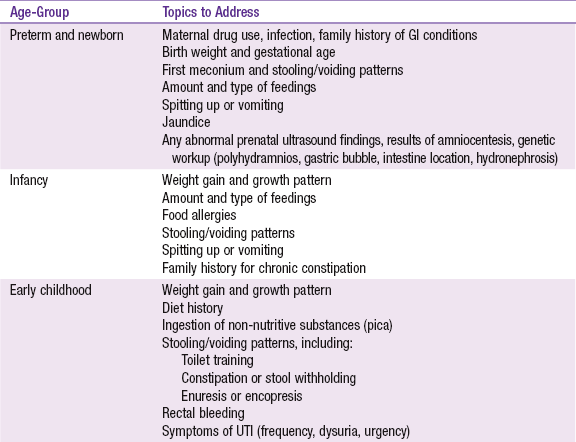

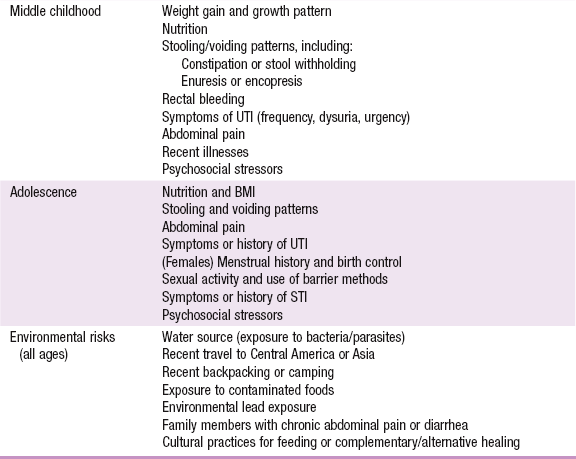

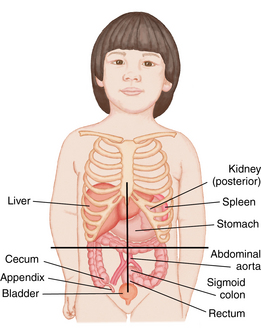

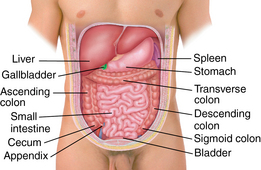

CHAPTER 14 Development of the kidney begins with a primitive, transitory structure called the pronephros, or forekidney, which arises near the segments of the spinal cord. These segments appear early in the fourth week of gestation on either side of the nephrogenic cord. The pronephros itself soon degenerates but leaves behind its ducts for the next kidney formation, the mesonephros, or midkidney, to utilize. In the fifth week, the metanephros, or hindkidney, begins to develop and becomes the permanent kidney. By the eighth week, the hindkidney begins to produce urine and continues to do so throughout the fetal period. The abdomen is the area of the torso from the diaphragm to the pelvic floor and is lined by the peritoneum, a serous membrane covering the abdominal viscera (Figure 14-1). The membrane of the peritoneum creates a smooth, moist surface that allows the abdominal viscera to glide freely within the confines of the abdominal wall. FIGURE 14-1 Abdominal structures. (From James SR, Nelson KA, Ashwill JW: Nursing care of children, ed 4, St. Louis, 2013, Elsevier.) Below the left diaphragm, from posterior to anterior respectively, lie the spleen, pancreas, and stomach. The spleen is a concave organ made mostly of lymphoid tissue that lies around the posterior fundus of the stomach. The spleen filters and breaks down red blood cells and produces white blood cells (lymphocytes and monocytes). It also stores blood that can be released into the vascular system during an acute blood loss. The pancreas is nestled between the spleen and stomach and crosses the midline over the major vessels. The pancreatic head extends to the duodenum and the tail reaches almost to the spleen. It is responsible for production of enzymes needed for the metabolism of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates; these enzymes are excreted into the duodenum via the pancreatic duct. The pancreas also produces insulin and glucagon, which are secreted directly into the bloodstream to help regulate blood glucose levels. The stomach is the most anterior organ in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. It is connected proximally to the esophagus, which enters through the diaphragm at the esophageal hiatus. The stomach receives food from the esophagus through the lower esophageal sphincter. It secretes hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes used to metabolize proteins and fats. When the stomach is distended, it is stimulated to contract and expel its contents through the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum, the first portion of the small intestine. The duodenum is C-shaped and curls around the head of the pancreas. The pancreatic and bile ducts empty into the upper portion of the duodenum. The duodenum then transitions to the jejunum, which is responsible for the majority of the absorption of water, proteins, carbohydrates, and vitamins. The ileum composes the last and longest part of the small intestine and absorbs bile salts, vitamins C and B12, and chloride. The intestinal contents leave the ileum through the ileocecal valve and empty into the cecum, located in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, which is the beginning of the large intestine. The appendix, a long, narrow tubular structure, arises from the base of the cecum. The large intestine lies anteriorly over the small intestine, ascends along the right anterior abdominal wall and forms the ascending colon, traverses across the abdomen to the splenic flexure forming the transverse colon, and descends along the left lateral abdomen wall as the descending colon (Figure 14-2). At the level of the iliac crest, the colon becomes the S-shaped sigmoid colon. It descends into the pelvic cavity and turns medially to form a loop at the level of the midsacrum. The sigmoid colon connects to the rectum, which lies behind the bladder in males and the uterus in females. It stores feces until it is expelled through the anal canal and out the anus, which is located within a ring of nerves and muscle fibers midway between the tip of the coccyx and the scrotum or vaginal fourchette. The anal canal and anus remain closed involuntarily by way of a ring of smooth muscle, the internal anal sphincter, and voluntarily by a ring of skeletal muscle, the external anal sphincter. FIGURE 14-2 Anatomical structures of the abdominal cavity in an adolescent male. (From Seidel HM, Ball JW, Dains JE, et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 7, St. Louis, 2011, Mosby.) The kidneys lie on either side of the vertebral column in the retroperitoneal space below the liver and spleen. The right kidney tends to be lower than the left because it lies below the right lobe of the liver. Kidneys have a lobulated appearance at birth, which disappears with the development of the glomeruli and tubules in the first year of life. The kidneys are perfused by the renal arteries and filter and reabsorb water, electrolytes, glucose, and some proteins. They regulate blood pressure, electrolytes, and the acid-base composition of blood and other body fluids; actively excrete metabolic waste products; and produce urine. The kidneys are capped by the adrenal glands, pyramid-shaped organs that synthesize, store, and secrete epinephrine and norepinephrine in response to stress. The adrenals also produce the corticosteroids, which affect glucose metabolism, electrolyte and fluid balance, and immune system function. Finally, a layer of fascia and then muscle cover the anterior abdomen. The rectus abdominis muscle extends the entire length of the front of the abdomen and is separated by the linea alba in the midline. The transverse abdominis and internal and external oblique muscles cover the lateral abdomen. The umbilicus lies in the midline usually below the midpoint of the abdomen (Figure 14-3). Information gathering for the assessment of the abdomen should include questions regarding diet, elimination, medications, environmental exposures and a thorough psychosocial history (see Information Gathering table). An assessment of the menstrual cycle in the female and history of sexual activity in adolescents is also essential (see Chapter 17). When a complaint of abdominal pain is reported, the examiner must elicit a detailed history of the pain. Information regarding the character and severity of the pain, onset and duration, location or radiation, position of comfort, things that alleviate or worsen the pain, history of trauma, and any associated symptoms of fever, vomiting, anorexia, constipation, or diarrhea is important in narrowing the scope of the differential diagnosis. A detailed history can help in determining whether the abdominal pain is acute or chronic. Remember that abdominal pain can be referred from an extra-abdominal source or can be a condition associated with systemic disease. For example, abdominal pain is common in children with beta-streptococcal pharyngitis, lower lobe pneumonia, sickle-cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and many other conditions. See Box 14-2 for differential diagnosis of symptoms or conditions related to different abdominal regions.

Abdomen and rectum

Embryological development

Anatomy and physiology

System-specific history

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Abdomen and rectum

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue