11.2 Low birth weight, prematurity and jaundice in infancy

Principles of care

• Keep the baby pink. Initial resuscitation should follow the usual ABC guidelines (see Chapters 5.15.2 and 11.1). After that, many babies will maintain breathing with supplemental oxygen until more sophisticated respiratory support is available. If an oxygen saturation monitor is available, give only enough oxygen to keep a preterm baby’s oxygen saturations between 86% and 94%, and a term baby’s saturations above 95%.

• Keep the baby warm. Cooling increases the baby’s oxygen and glucose requirements and is associated with increased mortality. Dry the baby and put a hat on to reduce heat loss while you are assessing other problems. Use a radiant heater, electric blanket or incubator if available.

• Keep the baby fed. Sick babies are at risk of hypoglycaemia, which can cause brain damage. If milk feeds are not possible, give intravenous 10% dextrose 60 mL/kg daily (2.5 mL/kg hourly).

• Consider infection. Almost any signs and symptoms of illness in the newborn can be caused by infection, and untreated septicaemia can cause death within hours. If specialized care is likely to be delayed by more than an hour or two, take blood cultures if possible and give intravenous or intramuscular antibiotics.

Definitions

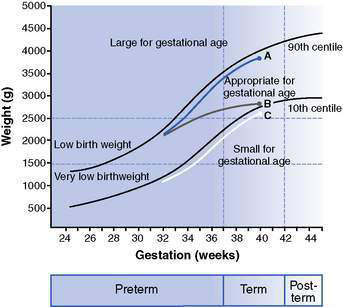

Babies are commonly classified into groups associated with different disease patterns and different outcomes (Fig. 11.2.1). These include:

The premature infant

Causes of preterm birth

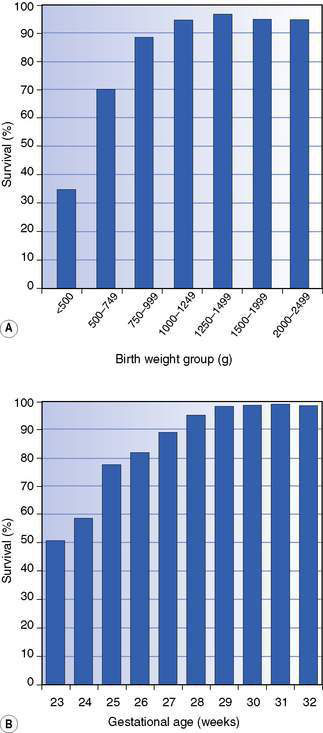

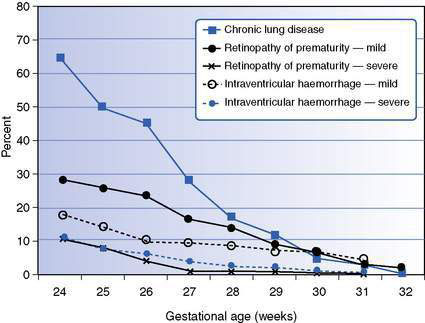

Although there are many risk factors for preterm birth (Box 11.2.1), approximately half of preterm births occur in the absence of recognized risk factors. Survival rates increase and the incidence and severity of complications all decrease with increasing gestational age and birth weight (Figs 11.2.2, 11.2.3, Table 11.2.1).

Fig. 11.2.3 Frequency of complications of prematurity in babies admitted to neonatal units according to gestational age.

(Source of data: Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network (ANZNN) 2009 Report of the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network 2006. ANZNN, Sydney.)

Table 11.2.1 Complications of preterm birth

| Common | Rare except in very low birth weight | |

|---|---|---|

| Early | ||

| Respiratory | Respiratory distress syndrome | |

| Apnoea | ||

| Cardiac | Patent ductus arteriosus | |

| Neurological | Periventricular haemorrhage | |

| Periventricular leukomalacia | ||

| Hepatic | Hypoglycaemia | Hyperglycaemia |

| Hyperbilirubinaemia | ||

| Renal | Hyponatraemia | Hyperkalaemia |

| Metabolic acidosis | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Feeding problems | Necrotizing enterocolitis |

| Other | Anaemia | |

| Infection | ||

| Poor thermoregulation | ||

| Late | Delayed growth | Retinopathy of prematurity |

| Chronic lung disease | ||

| Neurodevelopmental delay |