Background

Measures of contraceptive effectiveness combine technology and user-related factors. Observational studies show higher effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception compared with short-acting reversible contraception. Women who choose long-acting reversible contraception may differ in key ways from women who choose short-acting reversible contraception, and it may be these differences that are responsible for the high effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. Wider use of long-acting reversible contraception is recommended, but scientific evidence of acceptability and successful use is lacking in a population that typically opts for short-acting methods.

Objective

The objective of the study was to reduce bias in measuring contraceptive effectiveness and better isolate the independent role that long-acting reversible contraception has in preventing unintended pregnancy relative to short-acting reversible contraception.

Study Design

We conducted a partially randomized patient preference trial and recruited women aged 18–29 years who were seeking a short-acting method (pills or injectable). Participants who agreed to randomization were assigned to 1 of 2 categories: long-acting reversible contraception or short-acting reversible contraception. Women who declined randomization but agreed to follow-up in the observational cohort chose their preferred method. Under randomization, participants chose a specific method in the category and received it for free, whereas participants in the preference cohort paid for the contraception in their usual fashion. Participants were followed up prospectively to measure primary outcomes of method continuation and unintended pregnancy at 12 months. Kaplan-Meier techniques were used to estimate method continuation probabilities. Intent-to-treat principles were applied after method initiation for comparing incidence of unintended pregnancy. We also measured acceptability in terms of level of happiness with the products.

Results

Of the 916 participants, 43% chose randomization and 57% chose the preference option. Complete loss to follow-up at 12 months was <2%. The 12-month method continuation probabilities were 63.3% (95% confidence interval, 58.9–67.3) (preference short-acting reversible contraception), 53.0% (95% confidence interval, 45.7–59.8) (randomized short-acting reversible contraception), and 77.8% (95% confidence interval, 71.0–83.2) (randomized long-acting reversible contraception) ( P < .001 in the primary comparison involving randomized groups). The 12-month cumulative unintended pregnancy probabilities were 6.4% (95% confidence interval, 4.1–8.7) (preference short-acting reversible contraception), 7.7% (95% confidence interval, 3.3–12.1) (randomized short-acting reversible contraception), and 0.7% (95% confidence interval, 0.0–4.7) (randomized long-acting reversible contraception) ( P = .01 when comparing randomized groups). In the secondary comparisons involving only short-acting reversible contraception users, the continuation probability was higher in the preference group compared with the randomized group ( P = .04). However, the short-acting reversible contraception randomized group and short-acting reversible contraception preference group had statistically equivalent rates of unintended pregnancy ( P = .77). Seventy-eight percent of randomized long-acting reversible contraception users were happy/neutral with their initial method, compared with 89% of randomized short-acting reversible contraception users ( P < .05). However, among method continuers at 12 months, all groups were equally happy/neutral (>90%).

Conclusion

Even in a typical population of women who presented to initiate or continue short-acting reversible contraception, long-acting reversible contraception proved highly acceptable. One year after initiation, women randomized to long-acting reversible contraception had high continuation rates and consequently experienced superior protection from unintended pregnancy compared with women using short-acting reversible contraception; these findings are attributable to the initial technology and not underlying factors that often bias observational estimates of effectiveness. The similarly patterned experiences of the 2 short-acting reversible contraception cohorts provide a bridge of generalizability between the randomized group and usual-care preference group. Benefits of increased voluntary uptake of long-acting reversible contraception may extend to wider populations than previously thought.

Related editorial, page 98 .

One of the most startling reproductive health statistics in the United States is that 48% of unintended pregnancies occur in the same month when contraception is used. Poor adherence, incorrect use, and/or technology failures are to blame. Although short-acting methods such as oral contraceptives provide tremendous reproductive health benefit when used consistently and correctly, they can be unforgiving. Lapses in use occur because of side effects, temporary sexual inactivity, inconvenience of resupply/redosing, and other reasons.

The largest and longest contemporary contraceptive cohort study in the United States has shown superior effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). The 2 types of LARC are intrauterine devices and subdermal implants; once inserted, LARC provides at least 3 years of continuous pregnancy protection. LARC is highly effective (>99%) because it is not subject to errors in use that often reduce effectiveness of short-acting methods.

Whereas observational comparisons of effectiveness show superiority of LARC, on average, women who choose LARC may have priorities and needs vastly different from users of short-acting methods. These factors (eg, absolute and unwavering longer-term contraceptive needs) may draw women to LARC and may be the same factors determining contraceptive success, regardless of technology.

General measures of contraceptive effectiveness do not separate the independent roles that technology and user-related factors may have; nevertheless, it is common to attribute effectiveness solely to the technology. Widely cited economic analyses show higher cost savings with LARC compared with the short-acting methods. However, an important cost saving is from the reduction in unintended pregnancy, which can be explained in part by user characteristics and needs, not necessarily just the contraceptive technology.

Newly released prevalence data in the United States show use of short-acting methods is about 4 times higher than LARC use. A voluntary decision to try LARC (in lieu of using short-acting methods) could result in high satisfaction, avert unintended pregnancy, decrease the number of elective abortions, and provide substantial public health benefit.

Scientific evidence of LARC acceptability and successful use is lacking in a population that typically opts for short-acting methods. The objective of this study is to isolate the role that LARC may have in preventing unintended pregnancy in a high-risk population and to assess general satisfaction with the products.

Materials and Methods

We described the background, rationale, and enrollment results of this study in a previous publication. Briefly, from December 2011 to December 2013, we enrolled participants in an open-label, partially randomized patient preference trial to compare the effectiveness of short-acting reversible contraception (SARC) and LARC. The study was conducted at 3 health centers in North Carolina owned and operated by Planned Parenthood South Atlantic. The study was approved by the federally registered Institutional Review Board of FHI 360, the Protection of Human Subjects Committee.

Only women seeking oral contraceptives or the injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate were invited to participate (both new and continuing users), in order to draw from a population that often experiences unintended pregnancy and to measure the potential benefit of LARC uptake with more scientific rigor. (We specifically excluded women who came to Planned Parenthood South Atlantic for LARC).

Potential participants also had to meet the following eligibility criteria: 18–29 years of age, sexually active, no previous use of an intrauterine device, no previous use of a subdermal implant, not currently pregnant or seeking a pregnancy termination on the day of screening, and good follow-up prospects (participants had to provide an e-mail address and a currently working cell phone number, and be willing to be contacted).

Clients presenting for pregnancy termination were excluded for a variety of reasons, including insufficient space to conduct study procedures on abortion clinic days and concerns from Planned Parenthood South Atlantic medical leadership that the study would make a client’s visit very long and complicated and thus more stressful.

Study staff tested the e-mail address and cell phone number with potential participants during screening to verify that they worked. Women agreed to participate by signing the informed consent document. Participants received standard contraceptive information on the methods available and the out-of-pocket costs of using them.

To better estimate typical patterns of contraceptive use, we did not require any minimum duration of product use, and participants were free to switch methods or stop entirely and continue under observation. Also, we did not have mandatory follow-up clinic visits because such visits might artificially influence contraceptive use patterns.

In this trial, women started on their preferred form of contraception or elected to be randomized to either SARC or LARC. Randomized participants received a free LARC method or free SARC product for a year. Women in the preference group paid out of pocket for their contraception, had their contraception covered by private insurance, Medicaid, or the Medicaid Be Smart Family Planning Program or were able to use Title X funds (available only at 1 of 3 health centers) to cover some or all of their costs.

If randomly assigned to SARC, participants chose either oral contraceptives or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate paid injection fees to Planned Parenthood South Atlantic). If assigned to LARC, participants chose 1 of the following: subdermal implant, levonorgestrel intrauterine system, or a copper intrauterine device. LARC participants were informed they could have the product removed without charge at any time and for any reason.

If participants wanted to change their contraceptives after starting the first dose, the replacement methods were no longer supplied by the project. For those who chose randomization and after revealing the assignment, we asked whether they had hoped for SARC, LARC, or assignment did not matter as long as the product was free.

For randomization, we used opaque, sealed, and sequentially ordered envelopes for each health center. Block sizes of 2, 4, and 6 were randomly assigned and within each block, equal numbers of SARC and LARC assignments were generated in random order. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic staff proceeded to the randomization phase if the participant did not have further questions, agreed to be randomized, and requested that the envelope be opened. No blinding was used for any aspect of the trial.

This trial offered products currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and routinely available at Planned Parenthood South Atlantic:

- •

Intrauterine device marketed in the United States as ParaGard (a T-shaped plastic device containing 380 mm 2 of copper surface) with approved duration of 10 years.

- •

Subdermal contraceptive implant, marketed in the United States as Implanon or Nexplanon (containing 68 mg of etonogestrel) with approved duration of 3 years.

- •

Intrauterine system, marketed in the United States as Mirena (containing 52 mg of levonorgestrel) with approved duration of 5 years.

- •

Oral contraceptives (a variety of formulations were available) requiring daily dosing.

- •

Injectable contraceptive, containing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) with approved duration of 3 months.

Study size

To measure and compare discontinuation rates of LARC and SARC in different arms of the trial, we used published estimates and assumed 38% of SARC users and 19% of LARC users would stop using their product within a year. Based on our desire for 90% power to detect a 2-fold difference in the 12-month continuation rate, a 2-sided log rank test (α = .05), and an estimated 10% loss to follow-up, we estimated that each arm (preference SARC, randomized SARC, randomized LARC) needed 150 participants. Because we had no prior experience with partially randomized patient preference trials and did not know what proportion of women would agree to randomization, we proceeded with an abundance of caution and budgeted for 900 participants.

Follow-up data collection

If a participant returned for services, we recorded the reason for the visit and any contraceptive method provision, method switching, or LARC removal. Users randomized to SARC who chose oral contraceptives received 3 packs at each visit; quantities taken home by women in the preference group varied according to their individual plans and needs.

We collected data at 6 and 12 months through an online questionnaire to record contraceptive use patterns. Each participant received a $25 gift card for completing each questionnaire. Women were asked about the main reason for any method switching/discontinuation, incident pregnancies, and pregnancy plans. In the 12-month questionnaire, we asked participants about overall happiness with their initial method, whether they would ever use the method again, and whether they recommended that a friend/relative try the method; these questions were asked, even if the initial method was no longer being used.

Analysis

The primary comparisons for endpoint analyses involved the randomized cohorts: SARC vs LARC. Secondary comparisons examined whether SARC users’ experiences (preference vs randomized cohorts) were different. We defined contraceptive discontinuation as the first significant interruption in the use of the original short-acting or long-acting product.

For oral contraceptive users, we relied primarily on self-reports. Women who stated they were no longer using pills were classified as discontinuers, as of 1 day after the self-reported last dose. Some women stated that they were still using oral contraceptives, despite long lapses in use. In these situations, we defined them as discontinuers only if 14 or more days elapsed since taking the last pill; otherwise, they were considered active users.

For depot medroxyprogesterone acetate users, we considered 106 or more days without an injection as a discontinuation event. We relied on evidence of last injection, as documented in clinic visits at Planned Parenthood South Atlantic. For participants who claimed to receive an injection outside Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, we used the self-reported date of that injection. For LARC users, we used data from clinic visits and self-reports of product removal; in discrepant situations, we used Planned Parenthood South Atlantic clinic records for establishing the correct date.

We classified pregnancies as intended if the participant wanted the pregnancy at that time or sooner. Unintended pregnancies were those in which the participant stated she did not want a pregnancy at that time or ever. Pregnancies resulting in an induced abortion were classified as unintended. In most cases we used the self-reported estimated date of pregnancy; however, sometimes clinic visits provided more accurate information. This information was also used for contraceptive discontinuation events.

We used the product limit method to estimate the 12-month cumulative probabilities of method discontinuation and unintended pregnancy for the cohorts and for specific contraceptive choices within those cohorts. In addition, we used Cox’s proportional hazards regression as a supporting analysis to control for the potential confounding effects that participants’ background factors may have had on the endpoints.

Proportional hazards modeling was used for the following: (1) to explore whether LARC and SARC differences in risks of discontinuation and unintended pregnancy were maintained in the randomized cohort and (2) to determine whether the SARC experiences in the preference vs randomized cohort were indeed similar.

In the modeling exercise, we included only variables that were at least moderately associated with the cohorts ( P ≤ .1). We used Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests, Fisher exact tests, or χ 2 tests of association to identify any significant differences of subjects’ characteristics between the cohorts. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

For the pregnancy analysis, we applied intent-to-treat principles once the first dose was administered; thus, any unintended pregnancies after method switching or discontinuation were tallied against the first-used method. In routine care, insertion of a long-acting reversible contraceptive and oral/injectable medications SARC are not equivalent options from a patient’s perspective; thus, pure intent-to-treat principles (ie, including those who never initiated the assigned regimen) for data analysis are not applicable in this context.

In our study, trying (initiating) a randomly assigned method tests how the contraceptive technologies fend off a variety of threats to subsequent adherence; such factors often have direct bearing on reproductive health. Our desire to measure satisfaction with LARC (in a population that self-selected to SARC) is also consistent with this analytical approach. Intention-to-treat analytical decisions vary considerably in published reports.

Results

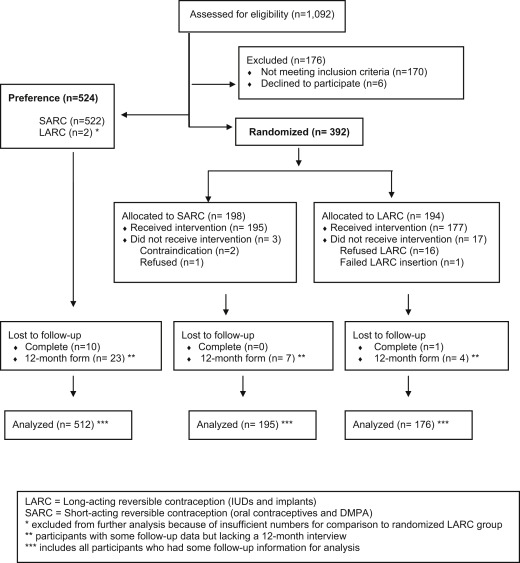

Staff at Planned Parenthood South Atlantic screened 1092 women for eligibility ( Figure 1 ). A total of 176 subjects were excluded, mostly because of ineligibility (n = 170): poor follow-up potential (n = 46), initial stated preferences for a method other than oral contraceptives or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (n = 36), previous LARC use (n = 24), not being sexually active (n = 20), and other reasons (n = 44). Of the 916 participants who remained eligible, 57% (n = 524) chose to be in the preference cohort of the study and 43% (n = 392) asked for random assignment.

We achieved our goal of recruiting at least 150 participants in the 3 study groups (preference SARC, randomized SARC, and randomized LARC).

A total of 896 participants started the contraceptive regimen and formed the cohort. Those who refused to start the randomized assignment (16 of 194 in the LARC group and 1 of 198 in the SARC group) were discontinued from the study, and no further contact was permitted. Ninety-five percent of the cohort completed a 12-month interview. Eleven participants (1.2%) were completely lost to follow-up. Two participants chose LARC in the preference cohort, but this quantity was insufficient for further analysis.

Cohort participants in the preference SARC, randomized SARC, and randomized LARC groups were similar in terms of age, marital status, race, ethnicity, education, pregnancy history, and other variables; approximately 25% had a previous abortion ( Table 1 ).

| Characteristic | Preference SARC (n = 522) n, %, or median (Q1–Q3) | Randomized SARC (n = 195) n, %, or median (Q1–Q3) | Randomized LARC (n = 177) n, %, or median (Q1–Q3) | P value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized groups | SARC groups | ||||

| Age | 23 (21–26) | 23 (21–26) | 23 (21–26) | .45 | .26 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 443 (84.9) | 168 (86.2) | 149 (84.2) | .85 | .37 |

| Married | 63 (12.1) | 18 (9.2) | 18 (10.2) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 16 (3.1) | 9 (4.6) | 10 (5.6) | ||

| Months with current partner | 15 (6–36) | 11 (3–25) | 12 (4–36) | .24 | < .01 |

| Race/ethnicity b | |||||

| Hispanic | 68 (13.1) | 30 (15.4) | 14 (7.9) | .09 | .58 |

| Non-Hispanic, white | 269 (51.8) | 105 (53.8) | 111 (62.7) | ||

| Non-Hispanic, black | 124 (23.9) | 44 (22.6) | 34 (19.2) | ||

| All other single and multiple race (non-Hispanic only) | 58 (11.2) | 16 (8.2) | 18 (10.2) | ||

| Education attainment | |||||

| Not complete high school | 20 (3.8) | 7 (3.6) | 9 (5.1) | .65 | .34 |

| High school | 199 (38.1) | 82 (42.1) | 73 (41.2) | ||

| Post-high school | 102 (19.5) | 26 (13.3) | 30 (16.9) | ||

| College | 157 (30.1) | 66 (33.8) | 57 (32.2) | ||

| Graduate school | 44 (8.4) | 14 (7.2) | 8 (4.5) | ||

| Currently working | 361 (69.2) | 148 (75.9) | 136 (76.8) | .83 | .08 |

| Health insurance | |||||

| None | 189 (36.2) | 93 (47.7) | 84 (47.5) | .93 | .01 |

| Private | 266 (51) | 87 (44.6) | 76 (42.9) | ||

| Medicaid | 45 (8.6) | 7 (3.6) | 8 (4.5) | ||

| Other | 22 (4.2) | 8 (4.1) | 9 (5.1) | ||

| Reproductive health | |||||

| Previous unintended pregnancy | 134 (25.7) | 59 (30.3) | 59 (33.3) | .52 | .22 |

| Ever had an abortion | 122 (23.4) | 53 (27.2) | 53 (29.9) | .45 | .45 |

| Number of previous pregnancies | |||||

| 0 | 366 (70.1) | 123 (63.1) | 110 (62.1) | .70 | .10 |

| 1 | 95 (18.2) | 47 (24.1) | 38 (21.5) | ||

| 2 | 33 (6.3) | 14 (7.2) | 18 (10.2) | ||

| 3 or more | 28 (5.4) | 11 (5.6) | 11 (6.2) | ||

| Months since last pregnancy ended | 15 (3–37) | 9 (1–23) | 10 (1–31) | .99 | .04 |

| Currently menstruating | 98 (18.8) | 34 (17.4) | 35 (19.8) | .56 | .68 |

| Wants more children | 440 (84.3) | 170 (87.2) | 136 (76.8) | < .01 | .33 |

| Months from today when pregnancy is desired | 60 (36–96) | 60 (48–96) | 60 (48–98) | .77 | .11 |

| Motivation to opt for randomization | |||||

| To receive free SARC | NA | 32 (16.4) | 9 (5.1) | < .01 | NA |

| To receive free LARC | 41 (21.0) | 67 (37.9) | |||

| To receive any free method | 122 (62.6) | 101 (57.0) | |||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree