Learning Problems

Michael I. Reiff and Martin T. Stein

Estimates of the prevalence of learning disabilities range from 4% to 20%, depending on how they are defined.1 Problems imposed by learning disabilities and different learning styles can significantly affect a child’s early sense of mastery and competence and can have lifelong implications on occupational functioning and psychological health. Learning disabilities cannot be diagnosed at an earlier age than the skills are expected to develop, but high-risk factors can be ascertained. Learning disabilities can be identified at any time throughout the school years. They may present with difficulty in individual subjects, underachievement, behavior problems, attention problems, and, eventually, school failure. If unrecognized, a chronic lack of school success can lead to low self-esteem, behavior problems, truancy, depression, high-risk behaviors of adolescence, and school dropout.

DEFINITIONS AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

LEARNING PREFERENCES AND STYLES

LEARNING PREFERENCES AND STYLES

Learning preferences and learning styles refer to an individual’s preferred modes of and different approaches to learning based on their individual strengths and weaknesses. Although various learning styles exist, the most commonly referenced types are auditory, visual, and kinesthetic (learning by doing). Ideally, students learn effectively using a combination of these styles. Those who do not are at a strong disadvantage if their school teaches in a manner that does not match their individual learning style. The intent of identifying learning styles or preferences is to enable a student to intake and output information in ways that are most comfortable and successful.

UNDERACHIEVEMENT

UNDERACHIEVEMENT

Underachievement refers to lower academic performance than expected based on abilities (IQ). It is reflected by poor grades and school-work production. It may also be accompanied by lower than expected performance on tests of academic achievement. Possible causes of underachievement include attention deficit hyper-activity disorder (ADHD), learning style and other educational issues, emotional and behavioral disorders, family and social factors, and engagement in high-risk behaviors such as drugs and delinquency. Underachievement can lead to or reflect poor self-esteem. Unaddressed, this may lead to school failure and dropout.

LEARNING DISABILITIES

LEARNING DISABILITIES

The most common definition of a learning disability is a significant to severe (1.5–2 standard deviation) discrepancy between a child’s abilities (as measured by an individually administered IQ test) and the child’s achievement (as measured by individually administered tests of achievement in reading, written expression, and mathematics).2 This model is often used to determine who qualifies for services in schools, and in some school systems, a child needs a discrepancy of 2 standard deviations before qualifying for services. The problems with this model are that few characteristics differentiate poor readers with discrepancies from those without discrepancies.1 In addition, the amount of discrepancy is not necessarily related to the severity of the learning disability3 and does not predict the reading level of a child over time in response to a reading intervention4 or how a child will respond to a given intervention.5 Using a discrepancy model, children with low average IQs and commensurate low average achievement (both 1.5 to 2 standard deviations from the mean) would not qualify for services; and there is no evidence that they would not benefit from educational services similar to those with normal IQs.

The Individuals with Disabilities Educational Act (IDEA) defines a specific learning disability as a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language (spoken or written), which may manifest itself in an imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations. This definition of learning disabilities includes such conditions as “perceptual handicaps, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia.”6 Federal regulations recognize learning disabilities in oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, reading comprehension, mathematics calculation, and mathematics reasoning that are not caused by a sensory or motor handicap; mental retardation; emotional disturbance; or social, cultural, and economic factors.

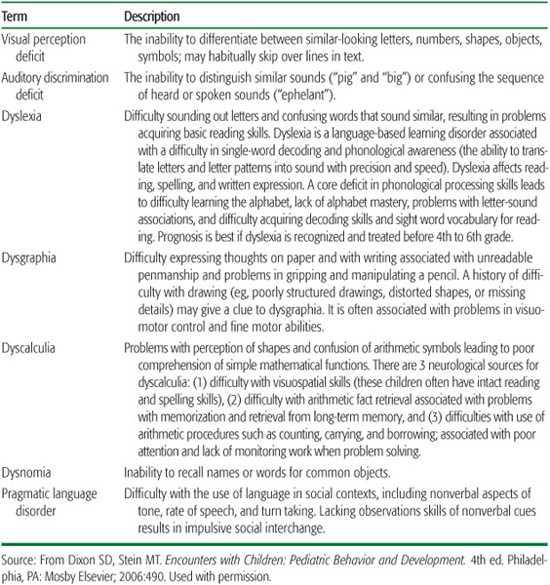

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR7 describes 4 categories of learning disabilities: reading disorder, mathematics disorder, disorder of written expression and learning disability not otherwise specified. According to the DS-MIV-TR, learning disorders are diagnosed when the individual’s achievement on individually administered, standardized tests in reading, mathematics, or written expression is substantially below expectation for age, appropriate educational experiences, and level of intelligence. The learning problems need to significantly interfere with academic achievement or activities of daily living that require reading, mathematical, or writing skills. If a sensory deficit (such as vision or hearing impairment) is present, the learning difficulties must be in excess of those usually associated with the deficit. Table 85-1 reviews a number of described learning disabilities.

Learning disorders may persist into adult life. In spite of these discrete definitions, there is a great deal of heterogeneity and overlap in learning disabilities. For example, there is little evidence for a learning disability in written expression in the absence of other learning disabilities. Coexisting conditions such as reading disability with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is more impairing than reading disability in isolation.

Table 85-1. Definitions of Learning Disabilities

NONVERBAL LEARNING DISABILITIES

NONVERBAL LEARNING DISABILITIES

Nonverbal learning disorder (NLD) is characterized by a specific pattern of relative strengths and deficits in academic skills. Reading and spelling skills may be well developed in association with weaknesses in social areas. Children with NLD make more efficient use of verbal than nonverbal information in social situations and thus have difficulty reading social cues. In some cases, it may be difficult to differentiate NLD from Asperger disorder (see Chapter 92). In children under 4 years old who have NLD, psychosocial functioning can be relatively typical or involve only mild deficits. Following this period, children with NLD may develop externalizing behavior and may present with hyper-activity and inattention. They are frequently perceived as acting out and hyperactive and are commonly identified by their teachers as over-talkative, troublemakers, or behavior problems. With advancing years, activity level can normalize and even become hypoactive. By older childhood and early adolescence, the typical pattern of psychopathology is internalizing in nature, characterized by withdrawal, anxiety, depression, atypical behaviors, and social skills deficits. Their interactions with other children are stereotypical, and their facial expressions lack affect. This stereotypical behavior is often accompanied by deficits in social perception, judgment, and interaction skills. The neuropsychological assets and deficits that characterize NLD are evident in a wide variety of pediatric neurological diseases and disorders such as Asperger disorder, early shunted hydrocephalus, velocardiofacial syndrome, and Williams syndrome. Children with NLD are particularly prone to serious psychosocial dysfunction over the course of their development compared to children whose learning disabilities are a result of phonologic processing. NLDs are less prevalent than language-based learning disorders (0.1%–1.0% of the general population).8,9

READING DISABILITY (DYSLEXIA)

NEUROBIOLOGY

NEUROBIOLOGY

Dyslexia is a neurobiologically based problem in reading in children and adults who otherwise have the intelligence and incentive necessary for accurate and fluent reading. It manifests with difficulties in word recognition and in poor spelling and word decoding (pronouncing nonsense words) abilities. Dyslexia is a persistent weakness in phonologic processing, the ability to analyze and synthesize phonemes (the smallest unit of recognized sounds). Dyslexia is persistent and does not represent simply a developmental lag in the ability to read.4 The estimated prevalence rates are 5% to 17.5% with an occurrence of 23% to 65% in children who have a parent with dyslexia. Replicated linkage studies suggest loci on chromosomes 2, 3, 6, 15, and 18.10

Speech is natural, but reading needs to be acquired and taught. To read, the beginner must be able to recognize that the letters and strings of letters represent the sounds of spoken language, that spoken words can be pulled apart into particles of speech (phonemes), and that the letters in a written word represent speech sounds. Deficits in phonologic awareness represent the most specific correlate of a reading disability.11 If phonologic awareness is impaired, then readers cannot use their higher-order cognitive abilities, such as their intelligence and other language skills, to access the meaning until the words are decoded and identified. Phonologic difficulties are independent of intelligence.

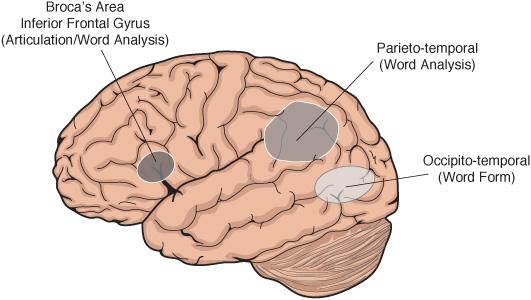

Brain anatomy and imaging studies have been employed to investigate the development of neurophysiologic processes involved in reading.12-14 These studies have shown differences in the temporoparietal-occipital brain regions between readers with dyslexia and nonimpaired readers. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of nonimpaired children demonstrate significantly greater brain activation in the left hemisphere (including the inferofrontal, superotemporal, parietotemporal, and middle temporal–middle occipital gyri) than is found in children with dyslexia. These studies demonstrate in children with dyslexia a failure of the left hemisphere posterior brain systems to function properly during reading as well as during nonreading visual-processing tasks.

The neurobiologic basis for dyslexia is a disruption of left hemisphere posterior brain systems while performing reading tasks. The evidence suggests that skilled readers use the left occipitotemporal word-identification area. The temporal lobes help distinguish sounds such as ba, ca, and da. Disruption of the posterior reading systems results in dyslexic children attempting to compensate by shifting to ancillary sites such as the Broca area inferior frontal gyrus (responsible for articulation and word analysis) and right hemisphere sites. These anterior sites are critical in articulation and thus may help children with dyslexia develop an awareness of sound structure through word formation, using lips, tongue, and vocal apparatus, and thereby enable the child to read, although more slowly and less efficiently than if the fast occipitotemporal word-identification system were functioning (Fig. 85-1). Functional imaging studies have also shown brain changes in a normalizing direction after the application of intensive phonological training of children with deficits in phonology.

Young adults with histories of childhood dyslexia may develop some accuracy in reading words; however, they remain slow readers. Others improve in accuracy, and as adults, they can be indistinguishable from nonimpaired readers on measures of reading comprehension. Persistently poor readers are more likely to have poorer cognitive/verbal abilities, attend more disadvantaged schools, and often have less linguistic stimulation at home.11

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

Risk factors for dyslexia in preschool children include a history of language delay, not attending to the sounds of words (such as trouble rhyming, confusing words that sound alike, mispronouncing words), difficulty learning to recognize letters of the alphabet, and a family history of dyslexia. A child with dyslexia in the early school years may have a history of delayed speech, not know letters by kindergarten, not begin to learn to read in first grade, and have difficulty sounding out words. Even after acquiring decoding skills (the ability to read single words in isolation), reading remains slow.15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree