Kawasaki Disease

Mary Beth Son and Jane W. Newburger

Kawasaki disease (KD), an acute febrile illness of childhood, was described in Japan in 1967 by Dr. Tomasaku Kawasaki as the mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome.1 A vasculitis of medium-sized vessels, KD has a predilection for the coronary arteries, and 20% to 25% of untreated children develop coronary artery aneurysms. Fortunately, a regimen of intravenous immunoglobulin and aspirin reduces the incidence of coronary artery abnormalities to less than 5%.2 Nonetheless, KD is a leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in North America and Japan. Furthermore, the etiology of KD remains elusive, impeding the development of targeted therapy and diagnostic testing.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND SPECIFIC POPULATIONS AT RISK

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND SPECIFIC POPULATIONS AT RISK

The Japanese Ministry of Health has collected epidemiologic data on Kawasaki disease (KD) since 1970 with nationwide surveys every 2 years. In total, over 225,000 cases of KD were reported in Japan between 1970 and 2006.3-5 The incidence of KD in Japan from 2005 to 2006 was 184.6 per 100,000 in children younger than 5 years of age.3

In the United States, Holman et al6 reported a hospitalization rate for Kawasaki disease (KD) in the United States in 2000 as 17.1 per 100,000 children less than 5 years of age, with a median age at admission of 2 years. Children of Asian and Pacific Islander heritage had the highest hospitalization rate at 39 per 100,000 children.

Risk factors for poor coronary artery outcomes have been identified in a number of studies. Young age, male sex and a number of laboratory parameters, including neutrophilia, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, elevated C reactive protein, and transaminitis have been associated with poor response to intravenous immunoglobulin or the development of coronary artery aneurysms.7-11 In short, younger, sicker children with worse systemic inflammation are at higher risk.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND GENETICS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND GENETICS

Despite years of extensive research, the etiology of Kawasaki disease (KD) remains obscure. Many aspects of the disease implicate an infectious trigger in the pathogenesis. KD is a disease of childhood, rarely seen in adults or infants less than 2 months of age. Discrete seasonal peaks with increased incidence in selected geographic areas suggest a transmittable vector.5,12 Many of the clinical features of KD resemble other childhood infections with exanthems (see below). However, no single etiologic agent has emerged as the clear culprit.

Similarities between Kawasaki disease and toxin-mediated diseases, such as toxic shock syndrome and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, led to the proposition that the features of Kawasaki disease are mediated by superantigens.

However, studies of T cells and attempts at isolating superantigen-producing bacteria in Kawasaki disease patients have yielded conflicting results.

CLINICAL FEATURES

CLINICAL FEATURES

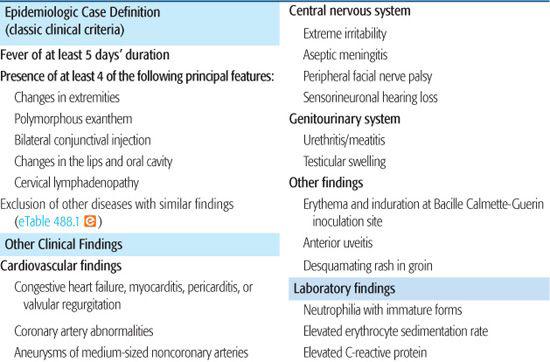

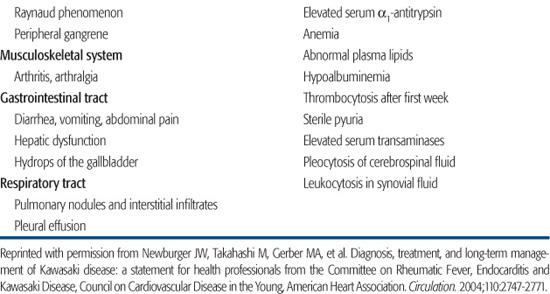

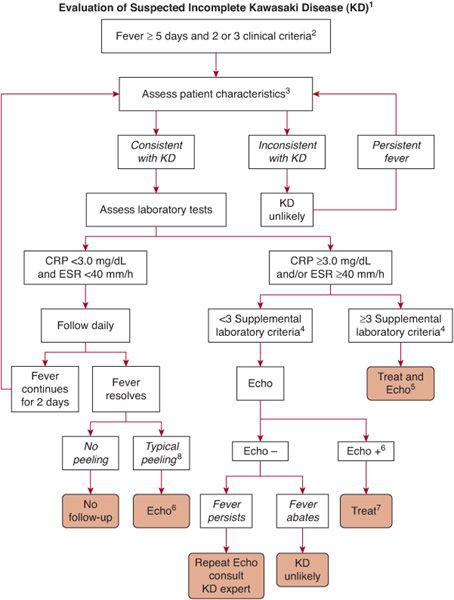

Classic clinical criteria, as well as supportive clinical and laboratory findings, are summarized in Table 488-1. In brief, the epidemiologic case definition of Kawasaki disease (KD) includes at least 4 days of fever (3 days in expert hands), together with 4 or 5 principal clinical criteria. Those with fewer than 4 principal clinical criteria may meet the case definition if they have coronary artery disease. Incomplete KD, in which fewer than 4 principal clinical criteria are evident, is associated with a rate of coronary aneurysms that is similar to that of complete disease. Because the diagnosis of incomplete KD is particularly challenging, the latest American Heart Association recommendations, endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, provide an algorithm for evaluation and treatment of suspected incomplete KD (Fig. 488-1).2

Table 488-1. Clinical and Laboratory Features of Kawasaki Disease

Fever is the hallmark of KD. Children with KD tend to have daily, high fevers (> 39°C) that are of abrupt onset. Without intravenous immunoglobulin treatment, the average duration of fever is 11 to 12 days, with rare patients remaining febrile for as long as 4 weeks. Patients who receive appropriate therapy tend to defervesce within 2 to 3 days of intravenous immunoglobulin administration. The clinical features that accompany fever in KD patients may appear and subside at differing times over the course of illness, highlighting the importance of medical history.

More than 90% of children with Kawasaki disease (KD) develop bilateral, marked conjunctival injection in a limbus-sparing pattern. Patients with KD develop mucosal changes in their oropharynx; diffuse erythema of the oropharynx, a strawberry tongue, and cracked, reddened lips are characteristic of KD, whereas exudative tonsillitis or discrete oral lesions suggest other etiologies. Typically, the rash is erythematous and begins in the perineal area with some desquamation; morbilliform and erythema multiforme lesions can also occur. Vesicular or bullous lesions suggest other diagnoses. Extremity changes in the acute phase of KD include erythema of the palms and soles, as well as edema of the hands and feet. In the convalescent phase of KD, usually 2 weeks after fever onset, periungual peeling occurs on the fingers, followed by the toes. The least common manifestation of KD is cervical lymphadenopathy, specifically a single large (> 1.5 cm) unilateral node that is usually nontender, without erythema or warmth. Diffuse lymphadenopathy is more likely explained by another diagnosis.

A variety of signs and symptoms may support the diagnosis of Kawasaki disease (KD). Patients with KD are usually irritable, perhaps reflecting central nervous system inflammation. Children with KD may complain of arthralgias; reported rates of frank arthritis range from 7.5% to 31% in KD patients.13Gastrointestinal complaints are also common and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Hydrops of the gallbladder can present with abdominal pain or jaundice or can be clinically silent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree