Early-Onset Sepsis

EVALUATION

Septic neonates can have dramatic clinical presentations characterized by respiratory failure, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), hypotension, or multiorgan failure. More challenging for health care providers, however, are more commonly encountered patients with subtle and nonspecific signs and symptoms or risk factors for sepsis. Considering the deleterious consequences of a missed or delayed diagnosis, a high index of suspicion is warranted when undertaking evaluation of neonates for potential sepsis.

Maternal History

Careful history is essential for determining key risk factors associated with early-onset sepsis (EOS). Clinicians should confirm the following:

1. Maternal group B streptococci (GBS) status.

2. Use of GBS-specific intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis vs broad-spectrum intrapartum antibiotic use.

3. Duration of time between rupture of membranes and birth.

4. Length of time of intrapartum antibiotic administration (>4 hours).

5. Intrapartum maternal fever.

6. Gestational age of the newborn.

Labor and Delivery

The clinical presentation of a septic infant can start as early as labor and delivery. Signs and symptoms may include the following:

1. Intrapartum fetal tachycardia.

2. Meconium staining of amniotic fluid.1

3. Low Apgar scores (newborns with an Apgar score ≤ 6 at 5 minutes had a 36-fold higher likelihood of sepsis than those with Apgar scores ≥ 7).2

Clinical Signs and Physical Findings

After birth, clinical signs of sepsis present in a range from nonspecific and subtle to severe multisystem dysfunction. More commonly presenting signs include the following:

1. Neurological: Temperature instability (fever or hypothermia, with fever more common in term newborns and hypothermia more likely in preterm neonates3); apnea; lethargy or irritability; hypotonia; weak cry; poor suck; seizures.

2. Respiratory: Tachypnea; respiratory distress (flaring, grunting, retractions, or decreased breath sounds); and pulmonary hemorrhage.

3. Cardiovascular: Tachycardia or bradycardia; cyanosis; hypotension; prolonged capillary refill time; mottled appearance; cool and clammy skin.

4. Hematological: Jaundice, petechiae, purpura, and pallor.

5. Gastrointestinal: Abdominal distension, feeding intolerance, emesis, diarrhea, bloody stools, and hepatomegaly.

6. Renal: Oliguria, anuria.

Diagnostic Tests/Laboratory Testing

Several tests are almost universally obtained for the evaluation of EOS; others are still limited by the lack of evidence to support widespread use:

1. Blood culture: This remains the gold standard for diagnosis of EOS. Although there is a considerably high incidence of false-negative cultures4,5 obtained from neonates, a culture absent of bacterial growth at 36–48 hours from a newborn with no other signs of EOS is reassuring. One small prospective cohort study has also examined utilizing cord blood for blood culture sampling in asymptomatic term newborns evaluated for sepsis based on the presence of risk factors.6 The authors concluded it may be a reasonable consideration, but additional studies are needed before a practice recommendation can be made. For those neonates who fail to demonstrate improvement after initiating empiric antibiotic therapy, repeating blood cultures is recommended, with expansion to other sites (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF], respiratory, and urine). If the initial blood culture is positive, blood culture(s) should be repeated 24 hours after antibiotics were initiated.5

2. CSF culture/studies: Meningitis in the newborn can be difficult to diagnose clinically. Although the decision to perform a lumbar puncture (LP) remains controversial, guidelines have been provided by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Fetus and Newborn for obtaining LP and CSF studies in a clinically unstable newborn or a newborn with a positive blood culture.7 Consideration for “holding” CSF stored in the laboratory in case additional studies are later needed should always be included in the discussion for performing the procedure. Serial LPs in the absence of an initial positive culture are not recommended because they are unlikely to yield additional benefit that outweighs potential risks and complications.

3. Complete blood cell count (CBC) with (manual) differential count: A CBC is the most readily available and commonly utilized test for EOS. It is typically done as a screening tool between 2 and 12 hours of life. However, values may range widely and be influenced by the timing of the sample acquisition. Serial studies at 6-, 12-, or 24-hour intervals are useful and, in conjunction with other laboratory results and clinical findings, can be recommended to influence the decision to discontinue antibiotic therapy.8,9 In sick neonates, thrombocytopenia is frequently observed, but it has no consistent predictive value. For a subset of patients, development of (worsening) thrombocytopenia may signal progression to septic shock or invasive gram-negative or fungal infection (premature infants).

4. Immature neutrophils (band cells + myelocytes + metamyelocytes) to total neutrophils ratio (I/T) 70.20 warrants a greater level of suspicion for EOS, especially in conjunction with other abnormal findings.10 Values less than 0.2 are usually considered within normal limits. An I:T ratio that “normalizes” within 24–48 hours, particularly in an otherwise-asymptomatic infant, can be considered a reassuring laboratory finding.

5. C-reactive protein (CRP): As an acute phase reactant, any inflammatory condition can elevate CRP. However, abnormally elevated CRPs obtained serially after birth can support a diagnosis of EOS. Furthermore, serial CRP values within normal range, particularly in the absence of other signs of EOS, may provide reassurance for discontinuing empiric antibiotic therapy.11 Serial CRP values are used by some centers to guide duration of empiric antibiotic therapy. Such protocols typically require at least two CRP levels, obtained 24 hours apart, with results below the laboratory’s designated cutoff to identify infants unlikely to be infected.12,13 We would caution against using this as a singular approach because there are still many unanswered questions about the value of CRP in managing neonatal sepsis. Research is ongoing and includes the intriguing possibility for point-of-care testing.14

6. Neutrophil CD64: Neutrophils have been shown to express CD64 when activated. Several studies have found CD64 determination to have high sensitivity and specificity for the determination of EOS when an appropriate cutoff value is selected. Advantages include small blood volume for sampling and rapid results. It is also considered advantageous when used in conjunction with CRP testing for EOS laboratory evaluations.15–17

7. Blood gas monitoring: Patients with sepsis often have metabolic or respiratory acidosis, hypoxemia (especially in PPHN), and hypercarbia. Frequent blood gas monitoring can alert the clinician to acute changes in the patient’s status that warrant urgent intervention. Arterial blood gas sampling is preferred for its accuracy.

8. Imaging studies: Imaging is helpful when respiratory symptoms predominate (chest x-ray) or there is a concern for intracranial bleeding as a complication of sepsis (cranial ultrasound). An echocardiogram is useful for ruling out congenital cardiac disease, assessing myocardial dysfunction, or determining the presence and severity of PPHN.

9. Electroencephalogram (EEG): For infants with an abnormal neurological status, including persistent lethargy, hypotonia, and seizure activity, in addition to a LP, an EEG evaluation in consultation with pediatric neurology may be warranted because neonates may have significant subclinical seizure activity requiring anticonvulsant therapy.

Differential Diagnosis/Diagnostic Algorithms

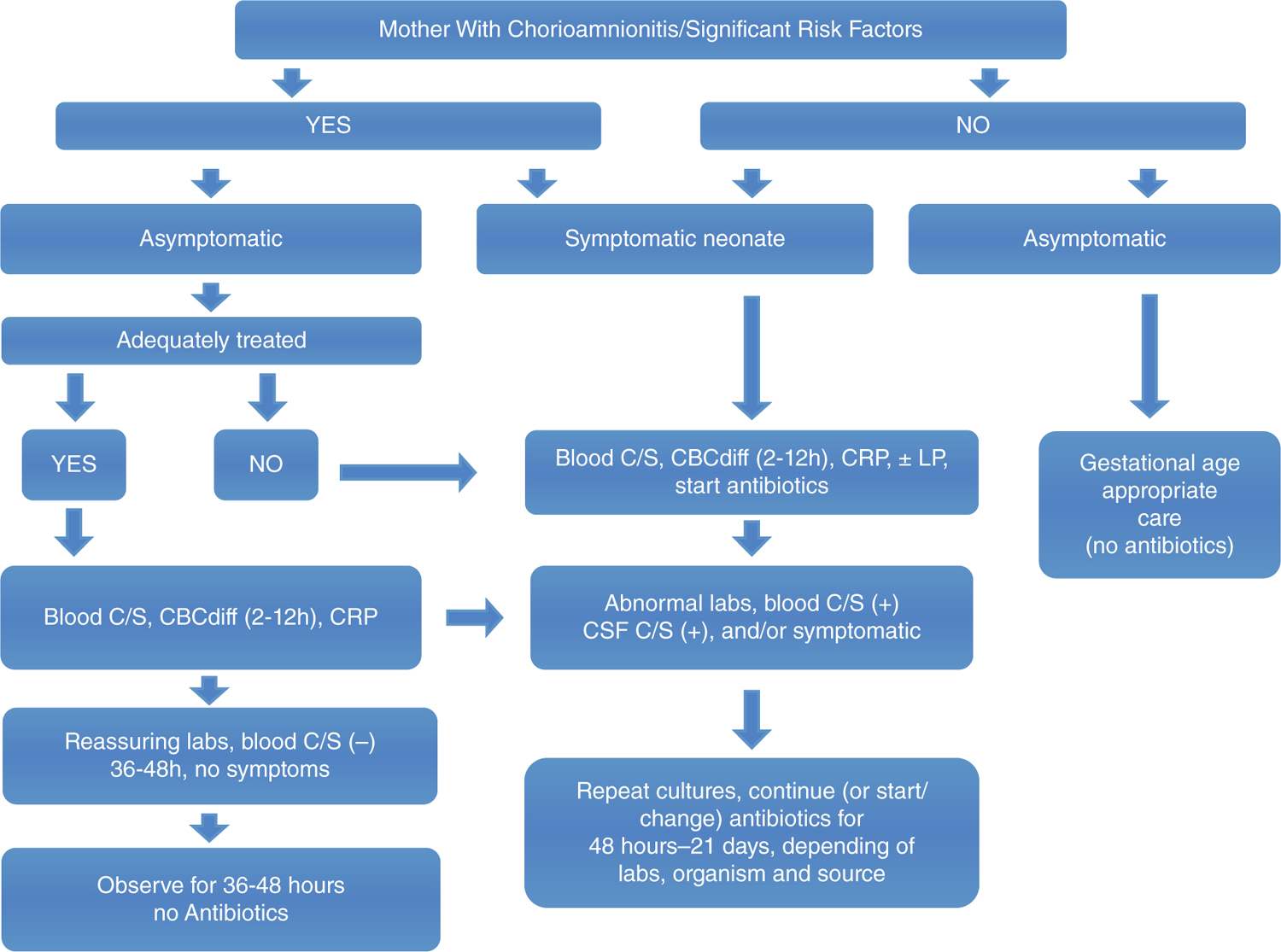

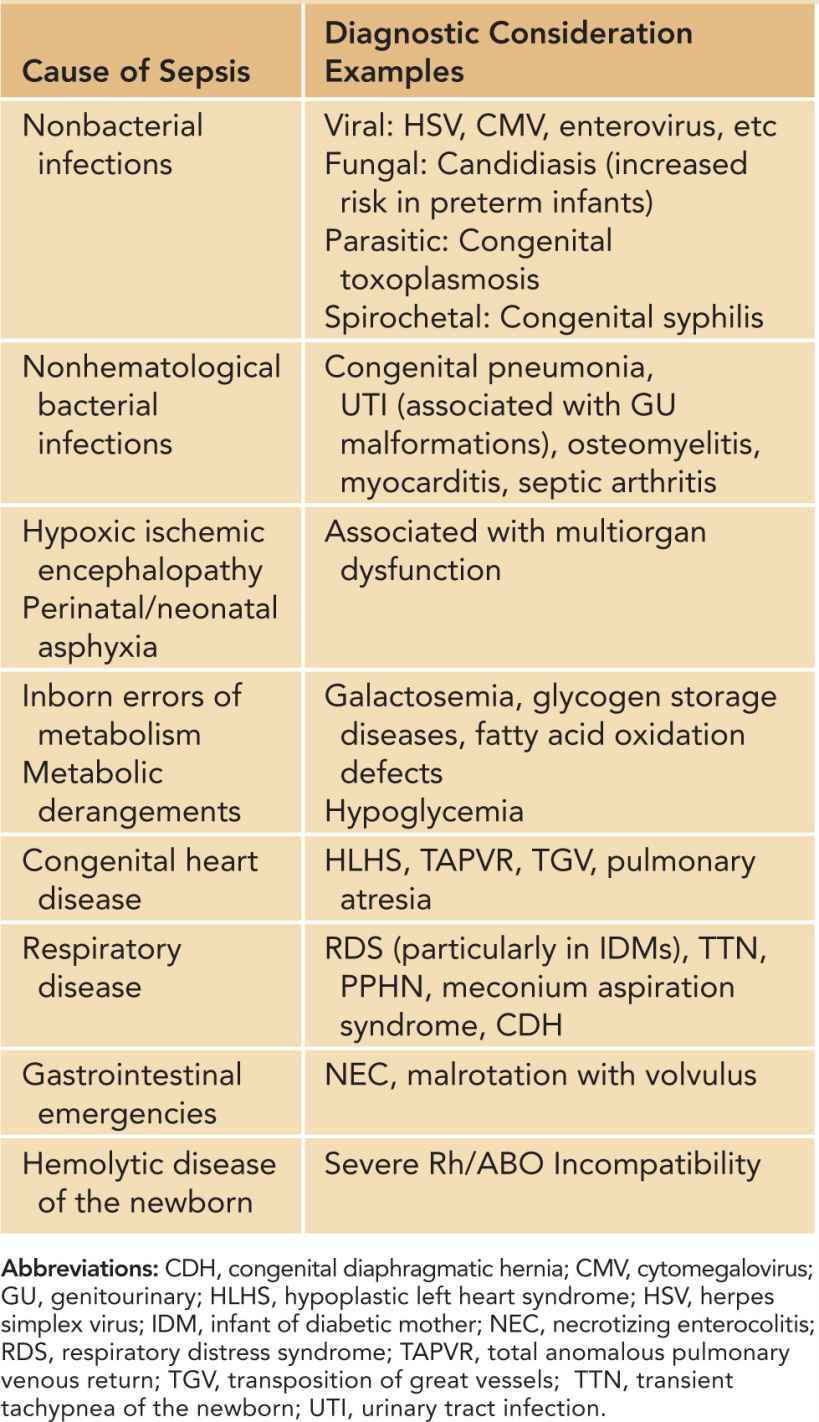

The differential diagnosis for EOS is broad (Table 113-1). However, given that EOS can mimic the presentation of other severe diagnoses, it is important to keep a complete differential in mind when evaluating a newborn. Figure 113-1 represents a diagnostic algorithm for EOS.

Table 113-1 Differential Diagnostic Considerations for Early-Onset Sepsis

FIGURE 113-1 Diagnostic algorithm for early-onset sepsis. CBCdiff, complete blood cell count with differential; CRP, C-reactive protein; C/S, culture and sensitivity; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree