Intestinal Obstruction

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Intestinal obstruction is a common condition in the neonatal period. Although precise data are not available, it is estimated to occur in approximately 1 in 2000 live births.1 Esophageal obstruction generally presents with respiratory symptoms and is not discussed here. Intestinal obstruction is frequently complete, as in intestinal atresia, or incomplete, as in duodenal stenosis. While the majority of obstructions are mechanical, others are functional, such as Hirschprung disease or meconium ileus. The ileus associated with septic or metabolic conditions may mimic intestinal obstruction and must be distinguished from obstruction, as it does not require operative intervention.

Associated conditions include genetic abnormalities or associated malformations. Trisomy 21 and duodenal atresia are associated2; meconium ileus is associated with cystic fibrosis (CF) and familial forms of Hirschprung disease. Imperforate anus is associated with esophageal atresia and renal or musculoskeletal anomalies, as in the VACTERL (vertebral, anal, cardiac, tracheoesophageal, renal, and limb) association.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The symptoms of intestinal obstruction may be catastrophic (eg, malrotation with midgut volvulus with ischemia or infarction) or relatively benign (eg, atresia of the duodenum or small intestine). The bowel proximal to the obstruction becomes dilated, presumably due to the effect of peristalsis against the obstruction, and the degree of dilation is considered to be related to the duration of the obstruction. The secretions of the intestine proximal to the obstruction accumulate in the dilated proximal bowel and result in vomiting or polyhydramnios. The vomitus is bilious in the majority of instances but will be nonbilious if the obstruction is proximal to the ampulla of Vater. If the vomiting is prolonged, the infant will become volume depleted and have electrolyte abnormalities.

Abdominal distension develops as the obstruction continues and is more prominent the more distal the obstruction is. Proximal obstructions (pyloric, duodenal, high jejunal) will have little or no distension. Distal obstructions, such as imperforate anus, Hirschprung disease, or distal ileal obstruction, will develop significant abdominal distension. Malrotation with volvulus will have no distension early in the process but once the bowel has become ischemic may have significant distension and abdominal tenderness. Abdominal tenderness and erythema are not associated with intestinal obstruction unless it is complicated by ischemia or perforation.

Failure to pass meconium or delayed passage may be associated with intestinal obstruction. Ninety-five percent of term infants will pass meconium during the first 24 hours of life.3 Of infants with Hirschprung disease, 60% to 95% will pass meconium after 24 hours following birth.4 Newborn boys with apparent imperforate anus are usually observed for up to 24 hours to identify passage of meconium through small openings on the perineum. The appearance of meconium or of white “pearls” on the perineum will identify a fistulous opening that can be probed to identify a low imperforate anus that is covered by an epithelial membrane as opposed to a high imperforate anus that will need either a colostomy or a primary pull-through procedure.

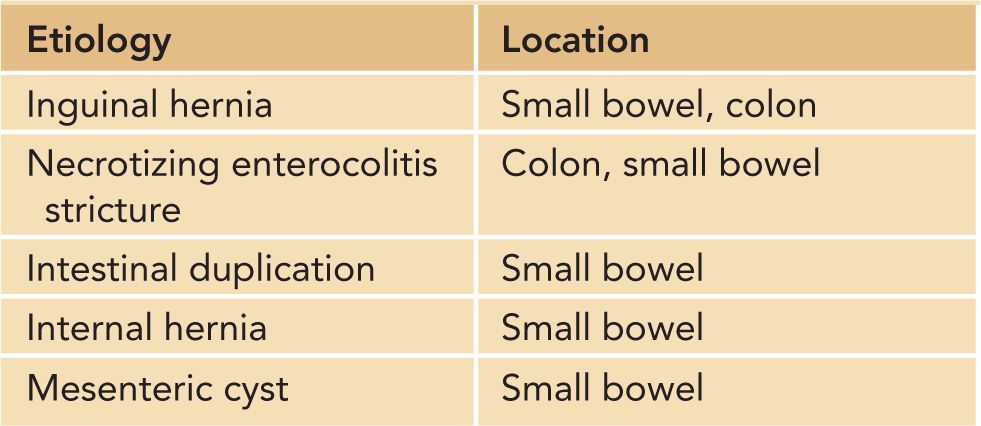

Other causes of obstruction are presented in Table 36-1.

Table 36-1 Other Causes of Neonatal Obstruction

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of intestinal obstruction depends on the symptom of obstruction that is being evaluated: polyhydramnios, vomiting, abdominal distension, or delayed passage of meconium.

Polyhydramnios is an infrequent complication of pregnancy (1%) and is determined by qualitative or quantitative criteria. The majority (60%) of cases are classified as idiopathic. Other causes include fetal malformations and genetic conditions (8%–45%), maternal diabetes mellitus (5%–26%), multiple gestations (8%–10%), and fetal anemia (1%–11%).5

Vomiting is a common symptom in newborns and is classified as bilious vs nonbilious and projectile or effortless. The most common causes of vomiting in neonates are gastroesophageal (GE) reflux, overfeeding, and gastric dysfunction due to prematurity, gastritis, or metabolic conditions. The emesis in obstructions that are proximal to the ampulla of Vater will be nonbilious. The vomitus in newborns with gastritis is typically brown, “coffee grounds,” or blood tinged. Infants with gastritis are also typically irritable due to the ongoing inflammation.

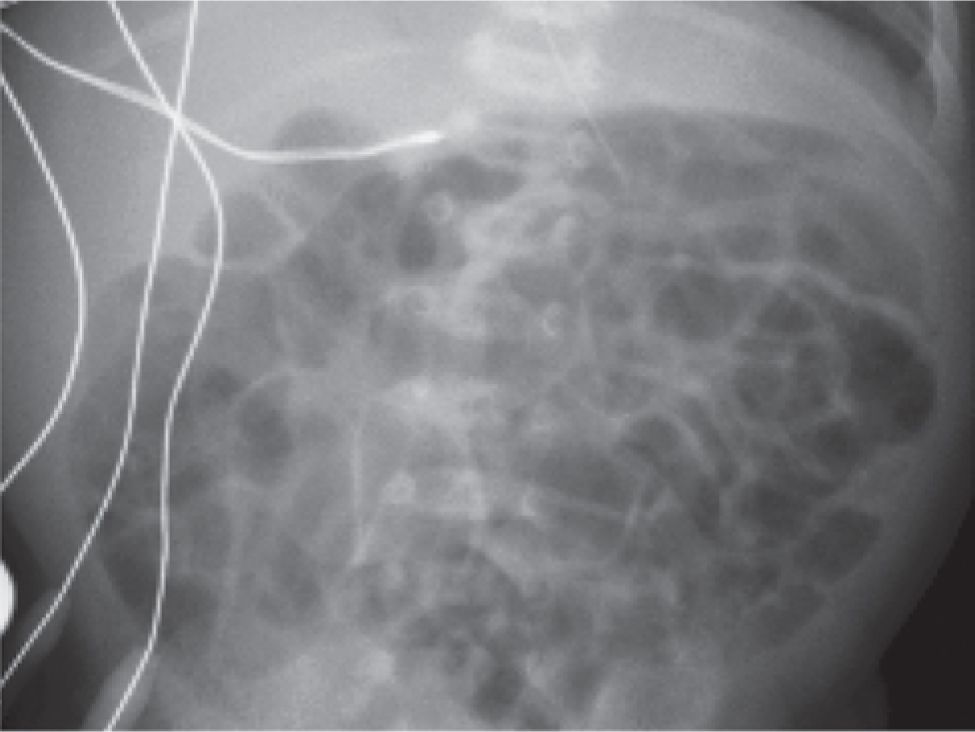

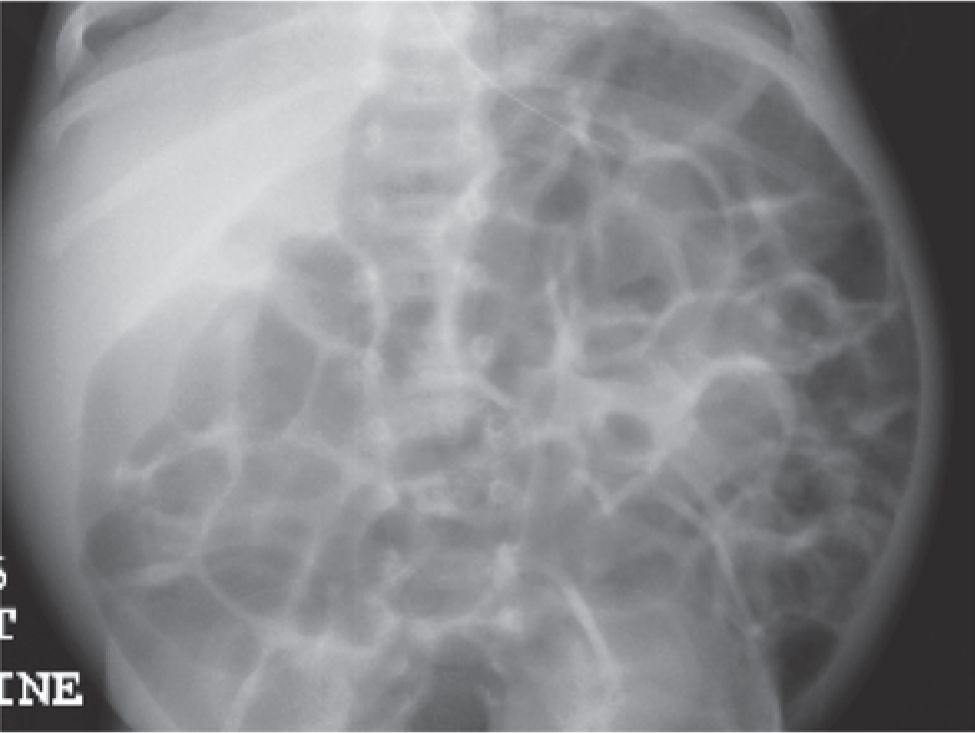

Abdominal distension (see Figures 36-1 and 36-2) is also common in newborns, particularly premature infants. Generalized abdominal distension may be due to ascites, gaseous or liquid accumulation in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, or rarely, large masses in the liver, GI or genitourinary tract, or retroperitoneum. Gaseous distension of the entire GI tract is typical of the ileus due to sepsis, metabolic conditions such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia, or the dysmaturity of the GI tract in premature infants. This last condition, characterized by repeated episodes of abdominal distension and feeding intolerance, results in frequent interruptions in enteral feeding and diagnostic investigations that may be unnecessary or associated with risk. These episodes are usually self-limited and eventually resolve as the infant approaches term.

FIGURE 36-1 Abdominal x-ray of premature infant with normal gas pattern.

FIGURE 36-2 Same infant with diffuse distension.

Delayed passage of meconium is a characteristic symptom of Hirschprung disease, with reports of 95% of affected infants passing their first meconium after 24 hours of age. Paradoxically, infants with complete obstructions of the GI tract may pass meconium or mucous stools as they are evacuating material that accumulated before the obstruction became complete or are emptying distal intestinal secretions to the point of obstruction.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

The diagnosis of intestinal obstruction can be suspected or defined during the prenatal period with ultrasound or fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). On ultrasound, obstruction is suggested by dilation of the bowel and vigorous peristalsis. Accuracy of ultrasound in this setting is low (34%), with greater accuracy for proximal obstructions such as those of the duodenum (52%) and small intestine (40%). The sensitivity for anal atresia is low, %8–10%.6,7 The sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting fetal obstruction is further compromised given that the routine timing for ultrasound anatomic survey is 20 weeks and that many of the obstructions may occur after this date.

Fetal bowel is well visualized by MRI, but the usefulness of MRI in diagnosing fetal obstructions appears limited as the majority of cases are identified by ultrasound; MRI has not been more accurate in the case of anal atresia.

After birth, most obstructions can be diagnosed accurately with the combination of history, physical examination, plain films of the abdomen, and contrast study of either the upper or lower GI tract. Ultrasound is useful in identifying ascites, abdominal mass, and malrotation. Ultrasound has also been used to evaluate malrotation.

MANAGEMENT

Stomach

Antral Web/Pyloric Atresia

Obstructions of the distal stomach and pylorus are rare, accounting for 1% or less of neonatal obstructions. Antral web was described in the 1970s as a mucosa-lined membrane near the pylorus that produces partial or high-grade obstruction. Recent reports have described more fibrous bands. The radiographic diagnosis consists of a thin band in the distal antrum. While operative resection of the web is the described treatment, there have been reports of responses to treatments directed at gastritis, such as acid blockers.

Pyloric atresia is extremely rare, with an incidence of 1:100,000 to 1:1 million live births. Approximately half of the cases are associated with epidermolysis bullosa,8 which should be assumed until excluded with careful attention to wound care. Diagnosis is suspected by air contrast films and can be confirmed with contrast if needed. Operative correction has been described as pyloroplasty or gastroduodenostomy.

Pyloric Stenosis

Pyloric stenosis is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in infants and frequently occurs during the neonatal period. The vast majority of cases occur in term infants who have developed nonbilious vomiting at home after an initial asymptomatic period of days to weeks. The emesis is frequently described as forceful or projectile, and the infants are typically hungry and happy between feeds, in contrast to infants with gastritis, who are frequently irritable.

Ultrasound is the preferred method of diagnosis and has high reliability. Wall thickness greater than 3 mm and pyloric length greater than 12 mm are considered abnormal, especially if combined with failure to identify fluid passing through the pylorus during the examination.9 The study must be performed systematically and with care to measure the wall thickness in a true perpendicular image. If the measurements are equivocal (2- to 3-mm wall thickness), a period of observation or repeat ultrasound is a reasonable strategy.

Once diagnosis is established, normalizing intravascular volume and electrolyte balance are the prime priority. Infants with pyloric stenosis may be 10%–15% dehydrated and suffer from hypochloremic alkalosis. This must be corrected before attempts at operative intervention to prevent arrhythmias associated with anesthesia. Fracture of the anterior wall of the pyloric muscle (pyloromyotomy) performed laparoscopically or by open approach has been the standard therapy for over 50 years. Recovery is rapid, with most centers allowing feedings beginning 4 to 6 hours following the operation and discharge at approximately 24 hours. In the days following operation, most infants continue to have emesis that is less severe and does not compromise hydration or electrolyte balance.

Gastric Volvulus

Rotation or twisting of the stomach along its long axis (organoaxial) or its short axis (mesenteroaxial) is a rare condition due to the normally extensive fixation of the stomach by its attachments to the diaphragm, spleen, and the anchoring effect of the immobile GE junction and the duodenum. Conditions such as malrotation, especially in the situation of asplenia or polysplenia, may predispose to gastric volvulus. This condition is marked by the sudden onset of severe vomiting or retching and rapid progression to cardiovascular collapse. Diagnosis is suspected from the unusual gastric bubble on plain films and confirmed by contrast studies that demonstrate obstruction at the GE junction or pylorus and elevation of the pylorus at times more cranial than the GE junction.

The treatment of gastric volvulus is operative anchoring of the stomach either by anterior gastropexy or gastrostomy. The procedure may be performed laparoscopically or open. Fixation of the stomach has been recommended at the time of correction of malrotation in the setting of poly- or asplenia and when the stomach is unusually mobile.

Duodenum

Atresia, Stenosis, Annular Pancreas, or Web

Atresia or stenosis of the duodenum occurs in 1:5000 to 1:10,000 live births, making it the most common intestinal atresia.10,11 The duodenum is the only

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree