Intestinal and Multivisceral Transplant

Simon Horslen

Intestine transplantation is now an established treatment for irreversible intestinal failure, allowing affected children the possibility to eat and drink normally while having an improved survival with good growth, development, and quality of life. Specific challenges in intestine transplantation include the technical considerations of graft procurement and implantation, ischemia and reperfusion injury to the graft, bacterial colonization of the intestine, and the complexity of the gut’s mucosal immune system.

Immunosuppression is critical to preventing cellular rejection and yet diminishes immuno-protective mechanisms.  Mucosal barrier function may be impaired because of ischemia or rejection, allowing increased bacterial translocation and increased risk of infection. Management of immunosuppression to balance infection risk versus rejection risk is especially narrow in intestine transplantation.

Mucosal barrier function may be impaired because of ischemia or rejection, allowing increased bacterial translocation and increased risk of infection. Management of immunosuppression to balance infection risk versus rejection risk is especially narrow in intestine transplantation.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Over the past 20 years, as the success of the procedure has improved, the number of intestine transplants has increased steadily to the current figure of about 200 intestine transplants per year worldwide. More widespread application is limited by: (1) the shortage of suitable size-matched, deceased donor organs and (2) the continued high rates of late graft and patient loss as a result of infection and rejection.2-6 The first of these factors mean that even if listed the mortality on the waiting list for intestine transplantation is the highest for any group of patients awaiting solid organ transplantation and is especially significant for the young children in need of composite intestine and liver allografts where pretransplant mortality has been reported as high as 60% of candidates.

INDICATIONS

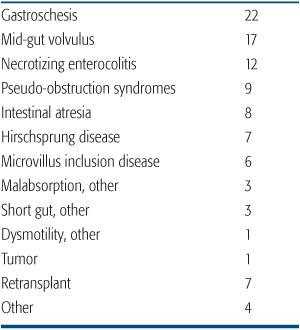

Intestinal failure, the inability of the gut to support one’s nutritional requirements, may result from a significant surgical resection, such as short bowel syndrome, disorders of intestinal motility, particularly pseudo-obstructive syndromes, and severe enteric mucosal dysfunction, for example, microvillus inclusion disease. All children with irreversible intestinal failure or complications of intestinal failure should be offered the opportunity for evaluation at an experienced pediatric intestinal failure program. This assessment assures optimization of the management of intestinal failure, including attempts to limit the complications associated with long-term parenteral nutrition. Causes of intestinal failure leading to intestinal transplantation are shown in Table 131-1.

Table 131-1. Indications for Intestine Transplantation in Children (% of total performed in the USA)

Long-term parenteral nutrition can be administered on an outpatient basis at home. This is commonly associated with good quality of life and adequate growth and development particularly for older children and adults. Therefore, uncomplicated intestinal failure is not in itself sufficient reason to contemplate intestinal transplantation.2 The fundamental indication for intestinal transplantation is irreversible intestinal failure with life-threatening complications. Such complications include progressive liver disease, recurrent severe infection, particularly fungemia, loss of central venous access sites, or uncontrollable enteral losses leading to metabolic or fluid instability.

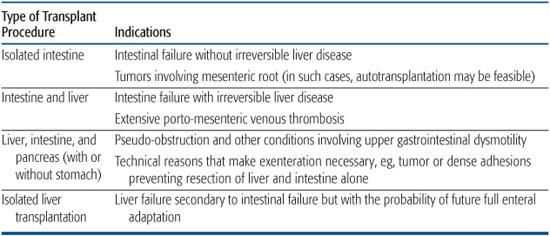

Types of organ transplants for intestinal failure are shown in Table 131-2, with general indications listed for intestine, liver, and composite transplantation.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Contraindications include active systemic infection, multisystem organ failure, severe congenital or acquired immunodeficiency, metastatic tumor, and severe cardiopulmonary or neurodevelopmental disease. Psychosocial issues such as inadequate family support, active drug abuse, or a history of noncompliance may make the transplant process untenable.

EVALUATION

The purpose of a multidisciplinary transplant evaluation is to determine if transplantation is an appropriate option for a given patient and, if so, which organs should be transplanted. The diagnosis should be confirmed and all treatment options short of transplantation must be considered. Relative contraindications should be considered. Comorbidities and other potential complicating factors need to be identified. The family needs to be informed about the procedure, the relative risks and benefits, treatment alternatives, outcomes including survival, and associated financial implications.3 A psychosocial assessment is imperative to identify family dynamics, coping strategies, and other emotional stressors.

The tests, consultations, and assessments are then discussed in detail at a multidisciplinary selection meeting to determine if transplantation is recommended and if the patient should be placed on the waiting list for transplant.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Donors are matched to recipients on the basis of blood group and size; typically, a donor smaller than the recipient is preferred, especially for recipients with short gut syndrome because of loss of peritoneal domain. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) matching is preferred, although not essential.

The transplant operation includes the removal of the failed organs and exposure of the vascular anatomy. Intra-abdominal adhesions and portal hypertension frequently complicate this step.

Vascular conduits may be required to provide optimal arterial inflow and venous drainage of the allograft. Intestinal venous drainage may be via the portal system or the systemic circulation. Intestinal continuity is established proximally, and an ileostomy created. Gastrostomy and jejunostomy access is frequently established to provide enteral access for feeding.

Primary abdominal closure may not be possible without undue tension because of large organs, allograft edema, or loss of peritoneal domain and may be facilitated by a temporary patch or silo closure.

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Intensive care admission is required following intestine transplant. Recipients of composite allografts tend to require more prolonged intensive care than those only undergoing intestinal transplant.

IMMUNOSUPPRESSION

IMMUNOSUPPRESSION

The common immunosuppressive regimens employed currently include an induction agent, either an anti-IL2 receptor antibody (basiliximab or daclizumab) or a lympholytic preparation (thymoglobulin or alemtuzimab), and maintenance therapy with tacrolimus with or without the routine use of steroids. Sirolimus may also be used as maintenance therapy in certain centers, but its use should be delayed until wound healing is assured.

INFECTION PREVENTION AND SURVEILLANCE

INFECTION PREVENTION AND SURVEILLANCE

Infection is common following intestine transplantation and is the leading cause of death in intestinal transplant recipients. Bacterial and fungal infections are the greatest risk in the first 4 to 6 weeks. Viral pathogens typically cause problems later post transplant. Routine surveillance for cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is common practice.

Table 131-2. Types of Transplants for Intestine Failure and Specific Indications

Postsurgical bacterial and fungal prophylaxis for the first 7 to 14 days is used. Long-term prophylactic regimens should include coverage for pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci and cytomegalovirus.4

FLUID, ELECTROLYTE AND NUTRITIONAL MANAGEMENT

FLUID, ELECTROLYTE AND NUTRITIONAL MANAGEMENT

Fluid and electrolyte management must address large postoperative fluid shifts and the need to optimize perfusion of the graft. Volume status, pulmonary function, and renal function also require active consideration. Additional fluid replacement is usually required to compensate for losses from gastric and abdominal drainage and wound losses. Following resolution of allograft ileus in the first week, secretory diarrhea usually occurs. Stomal losses of greater than 35 mL/kg/day are replaced with intravenous saline (0.45–0.9%), often with additional bicarbonate to avoid electrolyte imbalance. Once full feeds are tolerated, excessive stool losses can usually be managed with enteral replacement fluids.

Parenteral nutrition is required until full enteral feeding is possible, usually by 3 to 4 weeks post transplant. Continuous enteral tube feeding, using an elemental formula that is diluted to 15 kcal/oz, is started when intestinal motility returns, and oral intake can be introduced when gastric emptying has sufficiently recovered.

MONITORING ALLOGRAFT FUNCTION

MONITORING ALLOGRAFT FUNCTION

Clinical monitoring of allograft function includes assessing the appearance and perfusion of the stoma and daily stool volumes. Doppler ultrasound of the allograft is used to assess vascular patency, and in some programs to assess stomal perfusion. The mainstay of graft monitoring is endoscopy and mucosal biopsy. Routine surveillance ileoscopy and biopsy is performed at least once a week early posttrans-plant and whenever there is an unexplained change in intestinal function, primarily to rule out rejection. In the stable postintestinal transplant patient the frequency of endoscopic surveillance decreases over time.

POSTTRANSPLANT COMPLICATIONS

SURGICAL COMPLICATIONS

SURGICAL COMPLICATIONS

A high incidence of surgical complications can be seen following intestine transplantation due to the complexity and duration of the procedure, the history of previous abdominal operations, and advanced liver disease and suboptimal nutritional status. Complications include, but are not limited to, intestinal perfo-ration or obstruction, intra-abdominal bleeding or abscess, wound dehiscence or infection, vascular thromboses, and stomal prolapse. Allograft volvulus and internal hernia are important causes of graft obstruction and carry a high risk for graft loss resulting from ischemia. Reoperation in intestine transplant recipients ranges from 60% to 90% of cases.

INFECTION

INFECTION

Infection is not only the leading cause of death in intestine transplant recipients, but is also the primary diagnosis for readmission during all periods post transplant. Bacteremia or fungemia often has its source either intra-abdominally or in relation to long-term vascular access. In addition to appropriate antimicrobial therapy management should include the drainage of intra-abdominal collections, or removal of infected catheters.

Infectious enteritis may occur in almost 40% of intestinal transplant recipients; two thirds of the cases being attributable to viral agents. Adenovirus infections are common and caliciviruses can also be significant pathogens in this population. Viral pathogens may cause prolonged but ultimately self-limiting gastroenteritis but can also cause severe allograft dysfunction post intestinal transplant. Epstein Barr virus (EBV) is an important cause of viral illness presenting either as acute infection or as EBV-induced posttrans-plant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) occurs in about 10% of patients. Treatment for PTLD in intestinal transplant recipients follows the general steps outlined in other solid organ transplant recipients; however, the reduction in immunosuppression has to be done cautiously and with close allograft monitoring as devastating rejection, even in the face of active EBV, may occur.

GRAFT DYSFUNCTION

GRAFT DYSFUNCTION

Causes of acute graft dysfunction include acute cellular rejection, systemic or abdominal sepsis, infective enteritis, PTLD, and surgical complications such as intestinal perforation and obstruction. Clinical manifestations of graft dysfunction include irritability, fever, vomiting, abdominal distension, and changes in the appearance of the stoma. Stomal output may be increased, decreased, or bloody depending on the cause and severity of graft injury. Blood and stool cultures, viral studies, endoscopy with mucosal biopsy, and radiologic studies may all be required for exclusion of other causes for symptoms. Differentiation between viral enteritits and mild acute cellular rejection may be difficult and experienced pathological interpretation of the biopsy specimens is essential (see http://tpis.upmc.com). Viral culture, immunohistochemisty, and in situ PCR may assist with the diagnosis. A lack of precision with the diagnosis of graft dysfunction can lead to inappropriate changes in immunosuppression potentially exacerbating graft injury.

Acute Rejection

A standardized system for grading the histo-logic changes associated with acute rejection of an intestinal allograft has gained wide acceptance.5 Changes seen in mild rejection include multiple apoptic crypt epithelial cells with lymphocytic infiltration. More severe grades include increased inflammatory cell infiltration, crypt damage, mucosal architectural alteration, and, ultimately mucosal loss. The treatment of acute rejection is with intravenous methylprednisolone boluses (10–20 mg/kg/day) usually for 3 days and an increase in the background immunosuppression either by increasing the goal serum levels of tacrolimus or by the addition of another immuno-suppression agent. Endoscopy and biopsy are repeated to ensure adequate treatment and to document histological improvement. Antilymphocyte preparations are reserved for severe or steroid resistant rejection. Severe rejection with loss of mucosa may necessitate graft enterectomy, particularly if no regeneration is seen.

Chronic Rejection

The pathological lesion of chronic rejection is an obliterative arteriopathy of medium-sized vessels within the transplant mesentery and deeper layers of the bowel wall. Mucosal changes, if present, are nonspecific. Diagnosis requires full thickness biopsy that is usually available only after enterectomy, when graft failure is established. Clinical signs of chronic rejection may include gradually deteriorating allograft function with increased stool outputs or allograft stricture with extensive submucosal fibrosis. Currently there are no markers of the early stages of this disease process, and once established, chronic intestinal allograft rejection does not respond to increased immunosuppression.

OUTCOME

SURVIVAL

SURVIVAL

Short-term survival has improved with a number of centers reporting 1-year survival approaching 90% in their most recent cohorts.7 Late graft loss, however, results in 5-year survival of 50% to 60%, according to the international Intestinal Transplant Registry (ITR). Survival is significantly influenced by era of transplantation, experience of the transplant program, pretrans-plant status (home versus hospital), retransplantation, and induction immunotherapy.1,8

In patients surviving more than 6 months, greater than 70% have excellent graft function and ultimately 90% of surviving recipients do not require intravenous feeding. After intestinal transplantation, patients are generally able to achieve linear growth, maintain adequate muscle and fat stores and transition to an oral diet. Many children are able to achieve positive growth velocity, although catch-up growth sufficient to compensate for significant pretransplant stunting is uncommon.

QUALITY OF LIFE

QUALITY OF LIFE

Quality of life is considered to be good for survivors of intestine transplantation with the large majority returning to normal daily activities however formal assessments of quality of life in children have only recently been published. A study of long-terms survivors of intestine transplantation in childhood showed that children perceived their physical and psychosocial functioning to be equivalent to the normal control population, although their parents rated their children’s general health somewhat below that of other children.9

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree