Interviewing Techniques

Christopher F. Bolling

The medical history represents the single-most important opportunity to obtain individualized medical information. Since it is an opportunity and not a guaranteed source of information, the caregiver or patient during the interview may unknowingly miss critical data. Language proficiency, patient and caregiver cognitive abilities, readiness to change behavior, interest in seeking health care, and personal comfort with the practitioner are only a few factors that may influence the ability to obtain vital information. The information in this chapter can enhance the health care provider’s ability to obtain patient information and to delve more deeply into patient motivation and understanding than the classically structured patient history. It assumes that it is a caregiver of a patient that is being interviewed, but the principles described apply to interviewing patients when developmentally appropriate. A more detailed discussion of communication approaches is provided in Chapter 3.

THE CLASSIC HISTORY

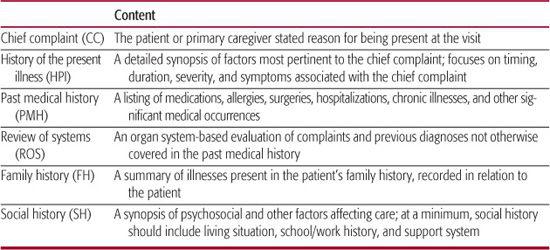

Table 4-1 describes the traditional patient history. The typical history focuses on gathering a variety of specific information in a brief period of time. The very important information recorded in the traditional history is an organized synopsis and a necessary summary of medications, surgeries, and major medical events. The degree of detail present in the various components is highly variable and should be tailored in response to the purpose and duration of the visit. The traditional history provides early valuable insight into factors influencing a patient’s motivation for seeking care.

Table 4-1. Components of the Classic Patient History

The challenge of the medical history is to not lose sight of the patient and caregiver’s often unstated goals. A significant hazard of the traditional medical history is losing valuable information that may not present itself if the patient feels overwhelmed with a long list of simple closed-ended questions.1 Approaching the medical history as a “laundry list” of simple questions with simple, 1-word, or yes/no answers, the health care provider will often prevent patients and caregivers from expressing pertinent concerns and from identifying barriers to care. Often, large parts of the medical history can be obtained from patients and caregivers in the form of surveys or questionnaires completed either independently or with the assistance of trained staff. Additionally, the first two components of the history, the chief complaint and history of the present illness, may be adequately addressed in some of the less directive techniques discussed in this chapter. Questions that necessarily lend themselves to simple answers can be “sandwiched” between more evocative and collaborative questions.2

WHY IS A COLLABORATIVE ARRANGEMENT BENEFICIAL?

Interviewing techniques represent far more than an information-gathering technique. Talking with caregivers lays the groundwork for later therapeutic intervention. Considering that the health status of adults in the United States is 50% determined by behavior and that the leading attributable causes of death are dominated by conditions modified by behaviors such as diet, smoking, and safety, provider ability to assist productive behaviors for health maintenance are highly desirable.3,4

The hierarchical nature of the doctor-patient relationship is long standing and established in a variety of disciplines.5 Rogers, in response to a culture of therapist-directed counseling, in the 1940s and 1950s described how therapists may be more effective in helping patients by forming a more collaborative relationship.6 In the 1970s, Prochaska and DiClemente7 introduced the transtheoretical model as a construct emphasizing the importance of patient readiness to accept prescribed treatment. They described a linear progression of patient readiness to change from a precontemplative state to contemplative, preparative, action and ultimately maintenance stages regarding specific behaviors.8 Miller and Rollnick further posited in the 1980s that physicians, counselors, dietitians, and other care providers in advice-giving professions may actually be harming their ability to modify patient behavior in a positive fashion.

Motivational interviewing, developed by Miller and Rollnick, provides a useful framework to improve the depth of data collected by the provider and can provide deeper insight into patient behavior. Motivational interviewing follows the patient centeredness of Rogerian theory, but unlike stricter interpretations of Rogerian practice, motivational interviewing is a directive technique. Providers may have identified harmful behaviors, but they hypothesized that consistent and repeated advice giving may actually engender patient resistance to behavior change.9 Current research by Resnicow10 goes further in describing the role of the provider as that of facilitator who helps set the stage for behavior change. The provider can increase the likelihood of behavior change by various actions and statements, but ultimate responsibility lies with patient and caregiver. Motivational interviewing suggests that the path to behavior adoption is not linear, as proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente, but rather is chaotic, progresses forward and back in readiness, and is fraught with expected relapses, failures, and false starts.

USING MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING

Miller and Rollnick described the “Spirit of Motivational Interviewing” as being based on 3 principles: collaboration, evocation, and autonomy. In a collaborative environment, health counseling involves a partnership that honors patient and caregiver expertise and perspectives. The atmosphere is conducive rather than coercive. Evocation implies that the motivation for behavior resides within the patient or caregiver. The provider can enhance pursuit of healthy behaviors by drawing on the caregiver’s own perception, values, and goals. Autonomy presumes the caregiver’s right and capacity for self-direction. The provider facilitates informed choices. Often a suggested course of action is met with a caregiver response of ambivalence. The provider should not be defensive but rather should recognize that the caregiver needs to further assess the costs and benefits of any particular action.

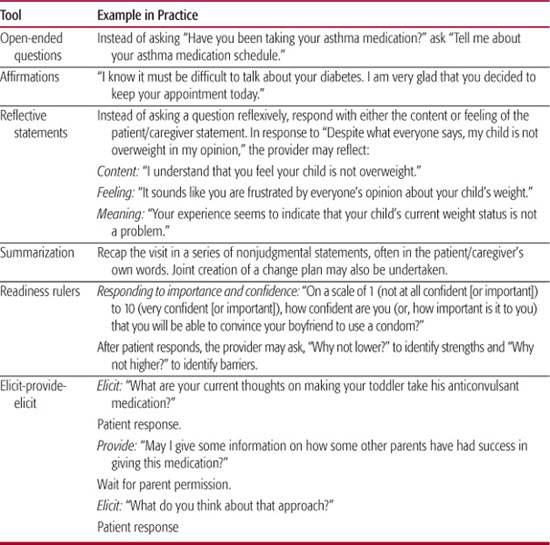

Tools for resolving ambivalence include increased use of open-ended questions, affirming statements, reflective listening, summarizing statements, readiness rulers, and a technique known as elicit-provide-elicit.11 Examples of these tools are given in Table 4-2.

Open-ended questions are questions that do not allow 1-word, simple, or yes/no answers. Furthermore, they are not leading or suggestive on the part of the provider. When discussing behavior, experts recommend 4 open-ended questions to every 1 closed-ended question. Open-ended questions are structured to require an engagement with the provider. They encourage caregivers to discuss their thoughts and to reflect on their own impression. They also indicate the provider’s desire to know more about the caregivers’ experiences.

Affirming statements are often simple acknowledgments of the caregiver’s struggles. Providers may enhance the collaborative environment by acknowledging the caregiver’s struggles without judging. Focusing on positive progress or simply seeking assistance can augment confidence, leading to an improved therapeutic relationship and a greater willingness to discuss sensitive topics.

The central skill in motivational interviewing is reflective listening. Reflective statements may reflect the content of what was just said, the underlying feelings the caregiver is expressing, or the conjectured meaning of the patient’s statement. Providers may be reluctant to attempt reflecting the meaning or feeling of a statement for fear of conjecturing incorrectly. Motivational interviewing encourages this attempt knowing that it will result either in affirmation that the provider understands the caregiver or an opportunity for the caregiver to clarify the feeling or meaning. Reflective statements should be phrased in such a way as to not imply a desired answer. Skilled motivational interviewing providers do not exhibit an “upward” concluding tone to declarative statements that will often elicit a confirmatory “yes” response. The desired intonation is a “downward” declarative tone that stimulates a conversational response. It is critical for motivational interviewing providers to be comfortable with periods of silence that sometimes follow in the normal course of conversation. Resisting the temptation to fill the vacuum is critical.

Table 4-2. Typical Motivational Interviewing Tools for Use in Brief Clinical Encounters

Summarizing statements are commonly used by providers and caregiver in collaborative relationships. They are effective as a tool to affirm the provider’s understanding and to clarify agreed-upon goals. Summarization provides an opportunity to formulate a collaborative care plan and incorporate other patient-tracking tools. In these ways, summarization can help keep a provider-caregiver interaction moving in a positive direction.

Readiness rulers or scales can help providers to assess the importance a caregiver attributes to a particular behavior and to assess a caregiver’s confidence in his or her ability to carry out that behavior. Caregivers may be asked to rate a behavior on a scale of 1 (low importance or confidence) to 10 (high confidence). The provider can then help the caregiver identify strengths that will help carry out a behavior by asking why the score was not lower and can identify barriers by asking why the score was not higher.

Elicit-provide-elicit is a summative strategy guiding a provider through a motivational inter-viewing–based sequence that seeks the caregiver’s thoughts (elicit), allows the exchange of information (provide), and follows the exchange with a further exposition of the caregiver’s thoughts (elicit). Central to elicit-provide-elicit are safeguards to avoid returning to unsolicited advice giving. Knowledge is often not the central deficit when detrimental behaviors are being followed. In the interest of providing a collaborative environment that respects the caregiver’s autonomy, permission must be granted by the caregiver before the provider supplies factual knowledge or expert opinion. Bracketing this specific information with reflective statements and open-ended questions promotes evocation powered by the caregiver’s inherent values, perceptions, and goals.

THE CHALLENGE OF AGE

A particularly vexing problem in pediatrics is deciding when a behavior is in the domain of an adult caregiver and when that behavior is in the domain of the pediatric patient. The preverbal 1 year old is clearly primarily influenced by the decisions of his caregiver. Conversely, the 18-year-old adolescent is making the transition to adulthood and is often not heavily influenced by parents on daily decisions. No comprehensive studies have been performed to definitively say when these collaborative techniques should be transitioned from caregiver to patient in pediatric settings. Providers should consider patient cognition, family dynamics, school situation, and age in making this transition. For most children reaching typical developmental milestones, 8 years of age generally represents a transition point from primary parental control to patient decision making. Providers are well-served by engaging both parties from 6 years of age on.

GOING FORWARD

Collaborative interviewing techniques such as motivational interviewing show great promise and are currently incorporated into a variety of clinical settings. The realm of self-management stresses collaborative techniques such as care planning and decisional aids. Within this context, extension of the collaborative environment to early information gathering is highly consistent.

Motivational interviewing and collaborative techniques are an increasingly sophisticated discipline. Experiential training in motivational interviewing can occur in a variety of workshops. The assessment of the effectiveness of motivational interviewing is ongoing and encouraging but, as of this publication, incomplete. Providers interested in these techniques are encouraged to participate in ongoing evaluation of training validity and fidelity and to evaluate for clinical effectiveness. Further information on these techniques and training opportunities are available at http://www.motivationalinterviewing.org  .

.

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree