Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Michael C. Stephens, Subra Kugathasan, and Thomas T. Sato

Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), collectively known as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), are idiopathic, lifelong, chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract which typically manifest during late childhood to young adulthood. The physical and psychological burden of these chronic relapsing diseases and their devastating effects imposed on affected children and teenagers may be considerable. Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are grouped together in view of many similarities in their epidemiologic, genetic, immunologic, and clinical features. Diagnostic approaches are similar, but treatment approaches and prognosis differ.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is unevenly distributed throughout the world with the highest disease rates occurring in industrialized countries of Europe, North America, and Australia.1,2 However, the incidence of IBD is rapidly increasing in other emerging industrialized countries. European studies have suggested that the incidence of IBD in children and adolescents has significantly increased over the last 35 years.3 Although population-based studies are difficult to perform in North America, an epidemiological population-based study in Wisconsin found the incidence of IBD to be 7 per 100,000 in children under 18 years of age.4 In children, about two thirds of IBD cases are Crohn disease (CD), and one half are ulcerative colitis (UC), and in the adult population the prevalence CD and UC are equal.5 The geographical and chronological variation of IBD since its description early in the 20th century is represented in eFigure 410.1  .

.

Onset of disease has a bimodal distribution, with the greatest incidence being adolescents and young adults, with a second peak in the fifth to sixth decade of life. Median age of onset of disease is between 10 and 11 years and is not different from CD. However, significant IBD cohorts have been described under 5 years of age.6 Population-based studies have not demonstrated an altered risk of IBD associated with gender, ethnicity, or urban versus rural setting.4 In adults, exposure to tobacco smoke is associated with a lower incidence of UC, but the opposite effect has been seen in CD.7,8 A prospective cohort study of childhood exposure to smoke (active or passive) showed an increased risk with smoke exposure for both CD and UC in adulthood.9 Appendectomy is associated with a decreased incidence of UC but appears to increase the risk for CD, especially for worsening of disease for the first year following surgery.10,11

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND GENETICS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND GENETICS

Inflammatory bowel disease was recognized as a disease entity during the early 20th century, and the pathogenesis has been linked to a combination of genetic, environmental, and microbial factors.14 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a disease of chronic gut inflammation. The most widely accepted theory of pathogenesis is that in genetically susceptible individuals, an environmental trigger promotes a chronic, dysregulated immune response. The environmental trigger may be an infectious agent such as a commensal organism of the normal gut flora or possibly a ubiquitous environmental agent.15 Following activation of the response, it appears that the mechanisms that attenuate the response may be defective in some individuals with IBD.

Crohn disease is heritable with specific genes associated with an increased risk of IBD.16 The comparative risk for Crohn disease (CD) in first-degree relatives of patients with CD is increased by up to 35 times, but the comparative risk for those of first-degree relatives of ulcerative colitis patients is approximately 3 times. Family history of IBD is present in less than 15% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).4,17,18 Sib-pair-based genome-wide linkage analyses showed a non-MHC association at the NOD2 gene on chromosome 16.19 More recently, the application of genome-wide association scanning (GWAS) has identified 30 confirmed loci to date.20

Several genetic susceptibility loci for UC have been identified, some in common with CD and others unrelated to CD. Loci common to both UC and CD include IL23R, IL12B, HLA, NKX2-3, MST1, CCNY, and 3p21.31. However, ECM1, PTPN2, HERC2, and STAT3 are associated with UC but not CD.22,23

CLINICAL FEATURES

CLINICAL FEATURES

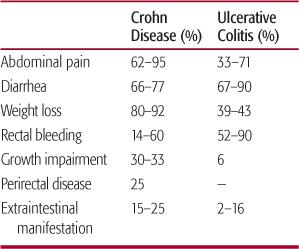

The clinical features of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) disease vary widely and depend upon the anatomic location(s) of involvement, extent of disease, and presence of extraintestinal manifestations.14,24 The frequency of common clinical features in pediatric patients with IBD is shown in Table 410-1. The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is classically based on a suggestive history of bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain, which may be associated with fever, whereas in Crohn disease the presentation is often more enigmatic. Up to 50% of children and adolescents with IBD present with mild symptoms, characterized by fewer than four stools per day and only minimal intermittent hematochezia. Children may also present without GI symptoms and only extraintestinal manifestations of IBD.

Common symptoms and signs include abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, rectal bleeding, growth impairment, perirectal disease, and extraintestinal manifestations. Fulminant colitis can occur at initial presentation or later. Patients with fulminant colitis are extremely ill, and often present with fever, chills, abdominal distention, nausea and vomiting, leukocytosis, significant anemia, dehydration, and deranged electrolyte balance. These patients are at risk for the development of toxic megacolon or perforation and require prompt treatment and intervention as detailed below.

Table 410-1. Presenting Clinical Features of Crohn Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Children

Abdominal pain is the most common symptom at presentation.25 The pain may not be localized, so differentiating pain caused by IBD from other causes of abdominal pain, such as functional abdominal pain, may be difficult. The pain is more likely to be chronic in nature, with a persistant location and severity. Terminal ileal or ileocecal Crohn disease is associated with a chronic history of right lower quadrant discomfort or pain. In contrast, the acute development of right lower quadrant pain without a past history of pain would more likely suggest a diagnosis of appendicitis.

The majority of children with IBD also present with diarrhea. Because the intestinal inflammation in ulcerative colitis (UC) is limited to the colon, a change in stool pattern is the most common presenting symptom for UC. Diarrhea in IBD is often nocturnal, and when the distal colon is involved, it can be associated with urgency and tenesmus. Rectal bleeding may vary in severity at presentation. Although gross blood is seen in most of the cases of UC, or in Crohn disease (CD) with colonic involvement, both UC and CD can present with diarrhea alone. Adolescents with CD are less likely to present with rectal bleeding than those with UC.

Weight loss, anorexia, and fatigue also herald the onset of UC or CD. Classically, most children had weight loss prior to the diagnosis of CD. However, more recent studies indicate that most children with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have a normal body mass index (BMI) at diagnosis.26 Less than 10% of children with UC have a BMI less than the fifth percentile at diagnosis compared to approximately 25% in CD. Twenty percent to 34% of children with UC have a BMI in the at-risk for overweight or overweight range at diagnosis (approximately 10% in CD). Growth failure is seen in between 13% and 58% of children with IBD28.

Delayed onset of puberty is common in Crohn disease (CD) and occurs less frequently in ulcerative colitis.30 This may have a substantial effect on linear growth because inflammatory bowel disease often presents in young adolescence.

Perirectal disease is common in CD and is not seen in ulcerative colitis. Approximately 25% to 30% of affected children with CD will have nonhealing deep anal fissures, fistulas, perirectal abscesses, or large, multiple anal tags.31 Surprisingly, perirectal pain is unusual unless there is actual abscess formation that may require prompt drainage. Enterocutaneous fistulas, such as perianal and perirectal fistulization (see eFig. 410.2  ), are the most common, compromising about 80% of the fistulas seen in CD.

), are the most common, compromising about 80% of the fistulas seen in CD.

A palpable abdominal mass (typically in the right lower quadrant) is not uncommon in patients presenting with CD. The mass may be inflamed intestine, or on occasion may represent abscess.

Rheumatologic, dermatologic, ocular, and hepatobiliary extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (listed in Table 410-2) are seen in up to 25% to 35% of patients with long-standing IBD. These may also be the sole presenting feature in pediatric IBD with no associated gastrointestinal symptoms. Axial arthritis (ankylosing spondylitis or sacroilitis) and peripheral arthropathy (knees, ankle, hips, wrists, and elbows) may precede the development of intestinal inflammation in IBD. Joint disease activity often corresponds with clinical bowel activity, but in a minority of cases, the course of joint inflammation is independent of any bowel disease. Finger clubbing, a form of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, can be seen in children with CD, particularly when the small intestine is involved. Erythema nodosum lesions (eFig. 410.3  ) appear as raised, erythematous, and painful nodules that occur over the tibia, lower leg ankle, or extensor surfaces of the arm. Pyoderma gangrenosum (eFig. 410.4

) appear as raised, erythematous, and painful nodules that occur over the tibia, lower leg ankle, or extensor surfaces of the arm. Pyoderma gangrenosum (eFig. 410.4  ) appears as a small, painful, sterile pustule that coalesces into a larger abscess, ultimately forming a deep, necrotic ulcer. Extensive small bowel involvement in CD may cause zinc deficiency with characteristic rashes.

) appears as a small, painful, sterile pustule that coalesces into a larger abscess, ultimately forming a deep, necrotic ulcer. Extensive small bowel involvement in CD may cause zinc deficiency with characteristic rashes.

Table 410-2. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Growth failure |

Dermatological: Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, sweet syndrome |

Eye: Episcleritis, uveitis |

Musculoskeletal: Sacroilitis, spondyloarthritis, axial arthritis, osteoporosis/osteopenia, finger clubbing |

Hepatobiliary: Sclerosing cholangitis, chronic active hepatitis, fatty liver, gallstones |

Hematologic: Anemia of chronic disease, thrombocytosis |

Vascular: Thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis |

Pancreatic: idiopathic pancreatitis |

Renal: Reanl caliculi (oxalate or uric acid), amoyloidosis |

Pulmonary: Granulomatous lung disease, reactive airway disease (rare) |

Cardiac: Myopericarditis and pleuropericarditis (rare) |

FIGURE 410-1. Large canker sores (Apthous ulcerations in the mouth) in a patient with Crohn disease.

Oral ulcers may be seen in many patients with IBD with varying severity (Fig. 410-1). Granulomatous inflammation involving the orofacial structures such as lips, gums, and face, have been reported to occur in a minority of patients at presentation (eFig. 410.5  ). Aphthous ulcerations involving the mouth and gums can be seen in many adolescents if a careful systemic evaluation is undertaken. Although rare, uveitis, episcleritis (eFig. 410.6

). Aphthous ulcerations involving the mouth and gums can be seen in many adolescents if a careful systemic evaluation is undertaken. Although rare, uveitis, episcleritis (eFig. 410.6  ), and iritis may be seen either as an existing presentation or a sole presenting manifestation of IBD in children. A slit lamp examination by an ophthalmologist is necessary to make such a diagnosis. Liver abnormalities including sclerosing cholangitis (see eFig. 410.7

), and iritis may be seen either as an existing presentation or a sole presenting manifestation of IBD in children. A slit lamp examination by an ophthalmologist is necessary to make such a diagnosis. Liver abnormalities including sclerosing cholangitis (see eFig. 410.7  ) or chronic hepatitis occur in both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease (CD). Several reports of idiopathic pancreatitis in patients with IBD, and as the presenting manifestation of CD, suggest that pancreatitis could be an extraintestinal manifestation of IBD. Pancreatitis can also be seen as a result of duodenal disease in CD. Urethral tract abnormalities or urinary obstruction may result secondary to ileocecal inflammation or a mass that involves the right ureter. Iron deficiency anemia secondary to chronic blood loss (either occult or overt) is more common during the initial presentation of CD than UC. When iron deficiency is seen in an older child or in an adolescent without any obvious source of blood loss such as menorrhagia, the suspicion for gastrointestinal blood loss and underlying IBD should be high.

) or chronic hepatitis occur in both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease (CD). Several reports of idiopathic pancreatitis in patients with IBD, and as the presenting manifestation of CD, suggest that pancreatitis could be an extraintestinal manifestation of IBD. Pancreatitis can also be seen as a result of duodenal disease in CD. Urethral tract abnormalities or urinary obstruction may result secondary to ileocecal inflammation or a mass that involves the right ureter. Iron deficiency anemia secondary to chronic blood loss (either occult or overt) is more common during the initial presentation of CD than UC. When iron deficiency is seen in an older child or in an adolescent without any obvious source of blood loss such as menorrhagia, the suspicion for gastrointestinal blood loss and underlying IBD should be high.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be based on clinical suspicion and subsequent screening laboratory workup that can lead to the definitive endoscopic or radiologic procedures.25 A detailed history and physical examination remain the most important aspects in the evaluation of a child with abdominal pain or symptoms suggestive of IBD. The indicators (“red flags”) in the history and examination that make a clinician suspect IBD in a child are listed in Table 410-3. Disorders that may present similarly to IBD are listed in eTable 410.1  . Exclusion of intestinal infections that can cause rectal bleeding such as enteric pathogens (Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, and E coli 0157/H7) and C difficile is imperative. Other considerations in children with abdominal pain and rectal bleeding include Henoch-Schonlein purpura, Behcet disease, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, tuberculosis, or vasculitis. When an abdominal abscess is found during the investigation of abdominal pain, in addition to CD, a perforated appendix, trauma, and gynecologic diseases must be considered.

. Exclusion of intestinal infections that can cause rectal bleeding such as enteric pathogens (Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, and E coli 0157/H7) and C difficile is imperative. Other considerations in children with abdominal pain and rectal bleeding include Henoch-Schonlein purpura, Behcet disease, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, tuberculosis, or vasculitis. When an abdominal abscess is found during the investigation of abdominal pain, in addition to CD, a perforated appendix, trauma, and gynecologic diseases must be considered.

Table 410-3. Clinical Indicators (“Red Flags”) in the History and Examination That Are Suspicious for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) in Children

History |

Abdominal pain |

Pain distant from the umbilicus |

Pain that interferes with normal sleep patterns |

Discrete episodes of pain which are of acute onset |

Pain precipitated by eating |

Dysphagia, odynophagia |

Involuntary weight loss |

Rectal bleeding |

Extraintestinal symptoms |

Unexplained low-grade fever |

Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum |

Joint pain, joint swelling |

Jaundice |

Severe eye pain or persistent conjunctivitis |

Growth problems, failure to thrive |

Strong family history of IBD |

Physical examination |

Paleness/anemia |

Decreased growth velocity |

Delayed sexual maturation |

Finger clubbing |

Oral ulcerations |

Abdominal tenderness, mainly right lower quadrant |

Abdominal mass |

Perianal fistula, fissures |

Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum |

Hemoccult positive stool |