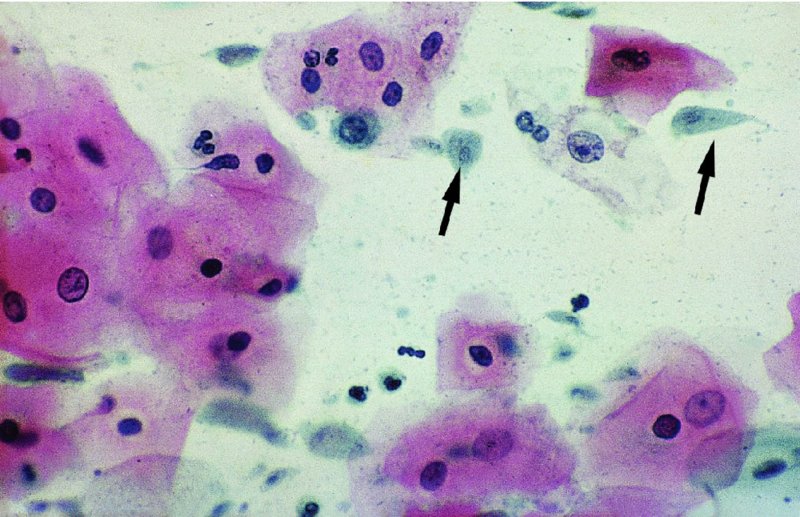

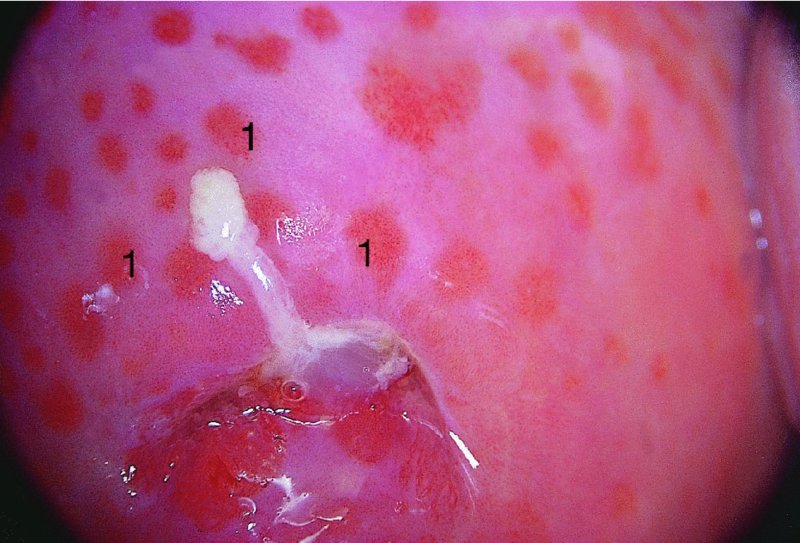

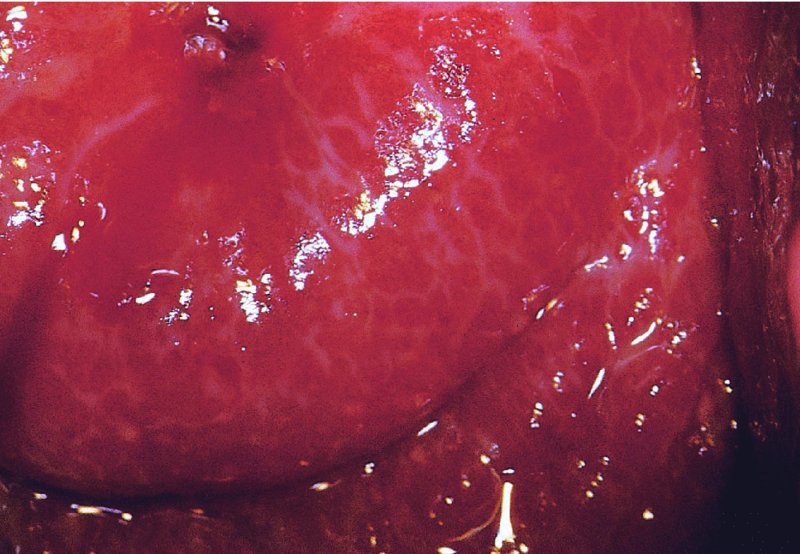

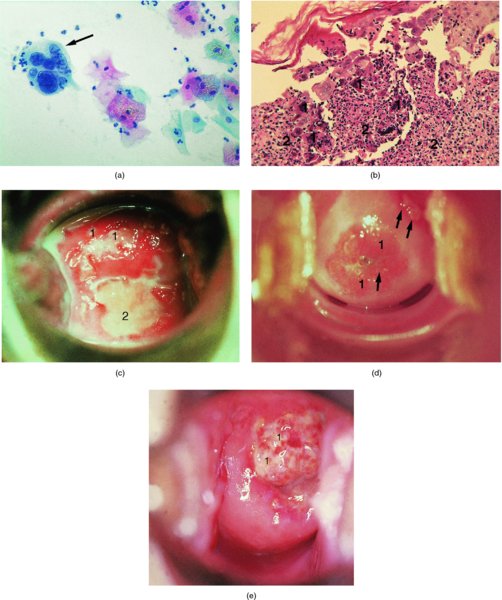

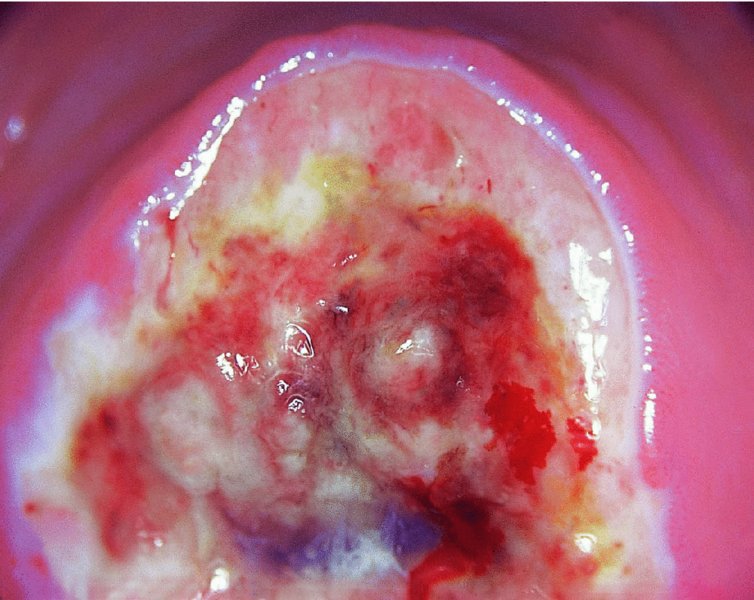

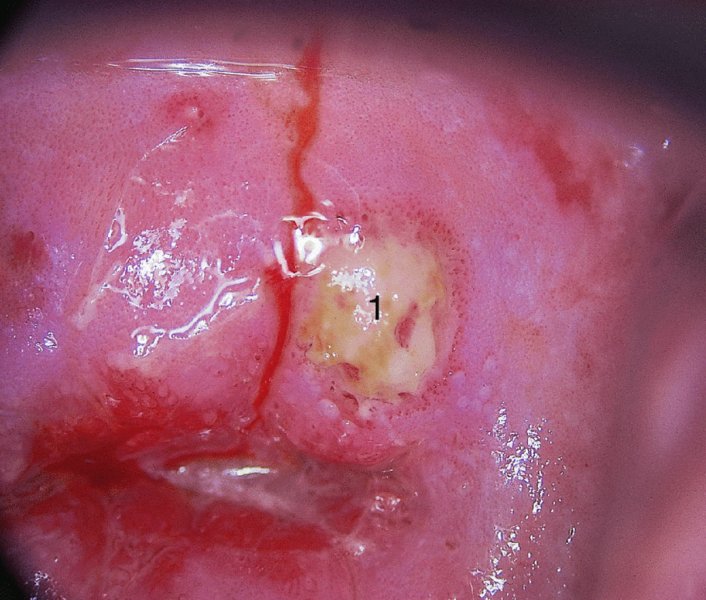

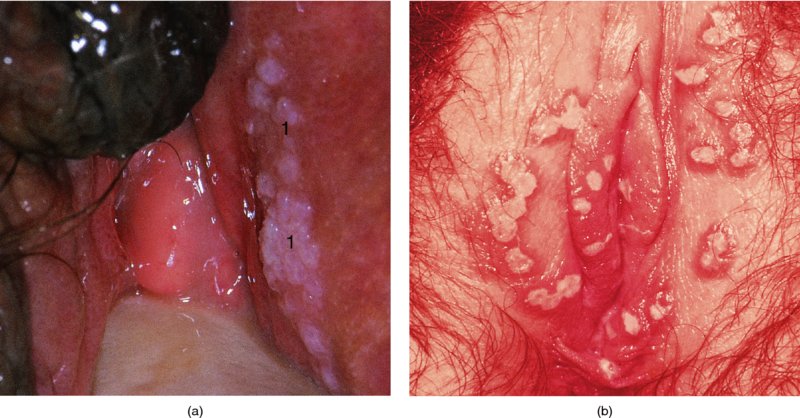

CHAPTER 12 There are many infective and other conditions that cause confusion in the diagnosis of genital tract precancer and cancer. The infective conditions can be of either a protozoan, fungal, or bacterial nature, and they cause widespread inflammation to the genital tract. Viral infections, especially by human papillomavirus (HPV), have already been discussed in detail, but it is important to recognize that they, in common with other infective agents, may well present diagnostic difficulties. The development of polypoid lesions and of the specific condition of cervical vaginal adenosis in pregnancy also cause problems, and all these have been considered. This common unicellular flagellate protozoan infects the lower genital tract in both men and women and is the most common sexually transmitted disease. Non-sexual transmission is uncommon because large numbers of organisms are needed to produce symptoms. Infection is not infrequently identified in cervical smears, with the characteristic appearance (Figure 12.1) of a small, blue–gray, ill-defined body with an elongated nucleus (arrowed). It is important to differentiate the Trichomonas from mucus and other cell debris on the smear. Although the Trichomonas protozoan is easily seen on a Papanicolaou stained slide, it is probably best identified using a wet mount preparation where the active Trichomonas can be easily seen. This is the most reliable method of diagnosis, although the sensitivity of the test is between 60% and 70%. More recent developments in diagnosis have consisted of the use of immunochromatographic capillary flow dipstick technology and nucleic acid probing. The sensitivity of the former test has been reported to be 83% with a specificity of 97%; results are available in 10 minutes in the former test and in 45 minutes in the latter test. These tests are valuable to the clinician when there is doubt about the status of the cervix; however, both cancer and this infective condition frequently coexist. Some women may be carriers of the disease and, under these circumstances, there is no active infection. The clinical and colposcopic appearances of the cervix are shown in Figure 12.2, where the characteristic strawberry patches can be seen. These strawberry patches (1) of cervicitis or vaginitis are characterized by a multitude of tiny red dots, each of which is the tip of a subepithelial capillary that reaches almost to the surface. In the worst cases, the infection is so intense that even minor trauma, such as taking a smear, produces intense bleeding. It is important that when a cervix is infected with Trichomonas, lesions such as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) should not be treated until the infection has been cleared, because gross bleeding can occur at this time. The infection is best treated using metronidazole or tinidazole. It is now accepted management that both partners are treated simultaneously with intercourse avoided and condom use encouraged until treatment has finished. Figure 12.3 illustrates a difficulty that can occur when a naked eye examination is made of the cervix and severe trichomonal cervicitis exists. Examination with the naked eye reveals a bleeding cervix that could be misinterpreted as bearing early invasive carcinoma. However, a colposcopic examination reveals the small, multiple subepithelial capillaries that have produced the generalized bleeding across the ectocervix. There is no evidence of invasive cancer This condition, previously called Gardnerella vaginitis, Haemophilus vaginitis, or non-specific vaginitis, is exceedingly common in reproductive women and its effect on the appearance of the cervix is similar to that produced by trichomonal vaginitis with both a strawberry spotted or a generalized inflammatory appearance (Figure 12.3). Because of these appearances a naked eye examination may raise the suspicion of a cervical malignancy which needs to be excluded. There is an alteration in the normal vaginal flora with the hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus decreasing in concentration, leading to an overgrowth of the Gardnerella vaginalis, anaerobic Gram-negative rods, and the Mobiluncus organisms. This leads to the production of a homogeneous vaginal discharge which has a characteristic fishy odor with a pH greater than 4.5. The homogeneous frothy discharge will produce this odor when potassium hydroxide solution is added. Microscopic examination of the vaginal secretions reveals the presence of clue cells which are more than 20% of epithelial cells with decreased numbers of lactobacilli and the presence of small Gram-negative rods. Candidiasis is the result of an overgrowth of the naturally occurring Candida albicans that is present in the mouth, throat, large bowel, and vagina. The condition tends to develop when there has been a change in the milieu or environment of the vagina. It is common in pregnancy and in association with diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), obesity, and drug therapy including oral contraceptives, corticosteroids, and antibiotics that kill the natural bacteria in the vagina that normally render the vaginal epithelium acidic. The spores and the pseudohyphae (filaments) of Candida albicans can be easily seen as thin red lines in cervical smears (Figure 12.4). They are also well demonstrated by a microscopic examination of the characteristic white creamy discharge both in a saline preparation or mixed with a potassium hydroxide (10%) solution. The vaginal secretions may also be cultured. The pseudohyphae may occasionally be colorless or pale blue, but are more commonly orange or red. The Candida produces an intense inflammatory response, and the epithelium of the cervix and vagina becomes thickened and covered with a creamy, curdy, white discharge (Figure 12.5). This must be differentiated from changes of leukoplakia or early malignancy on the cervix and vagina, and is best demonstrated by wiping away the lesions with a swab stick. If doubt exists, then saline should be used to wash the surface, after which a colposcopic examination will reveal a normal epithelial surface. Treatment of the condition is by the use of local agents, such as nystatin, clotrimazole, terconazole, and miconazole, in the form of a pessary or cream, or a systemic agent, such as fluconazole or itraconazole. These agents will commonly remove the infection completely. Again, male partners should be treated if evidence of symptomatic balanitis exist. Herpes genitalis is caused by infection with the herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV2). The disease is characterized by painful ulcers on the vulva and lower vagina, but when the lesion affects the cervix the infection is usually painless and is only found upon examination or colposcopy. When a patient presents with vulval or lower vaginal herpes, it is important to make a simultaneous and careful assessment of the cervix, and to advise about the high risk of transference of the virus to sexual partners. In the pregnant patient there is also a significant risk of transfer of the virus to the fetus during vaginal delivery. This risk is markedly increased during the patient’s first infection with the virus but it would appear that with subsequent infections the risk is markedly reduced. In extreme cases of very active upper vaginal and cervical infection, it is recommended that a Cesarean section should be carried out. The cytologic appearance of HSV infection is easily recognized. Figure 12.6a shows the cytologic changes in which the cells are characterized by large multiple nuclei that are molded together (arrowed) and show margination of chromatic and generally empty nuclei. Large intranuclear inclusions are also commonly seen. It is important to differentiate such cells from the binucleate cells that are commonly found in association with HPV infection, and from the bizarre appearances that may be associated with an invasive carcinoma and that are commonly generated following radiotherapeutic treatment of the cervix. Figure 12.6 (a–e) The cytologic changes of early infection are characterized by large intranuclear inclusions, and, as the infection progresses, a non-specific acute necrotizing cervicitis develops; this is represented cytologically by the appearance of degenerate and necrotic cells in which the ghosts of the nuclei can just be recognized. These necrotic cellular appearances have to be differentiated from those that are sometimes associated with clinical invasive squamous cell carcinoma or, indeed, occasionally with the intraepithelial stages of disease. The epithelial changes that occur with herpetic infection can all be recognized colposcopically; indeed, the early stages are best studied with the magnified illumination provided by colposcopy. The infection starts in the parabasal cells of the squamous epithelium; there is nuclear enlargement and the development of multinucleate cells, as described above. Vesicle formation and ulceration follow within approximately 36 hours, by which time a histologic examination of the vesicles (Figure 12.6b) shows them to be composed of giant cells at the edge (1) and in the base; polymorphonuclear leukocytes (2) are present in the surrounding epithelium. There may also be some basal cell hyperplasia present in the surrounding epithelium. Figure 12.6c,d shows the colposcopic changes of this early infection with vesicles (arrowed) and epithelial “congestion” (1) caused by cellular infiltration that occurs just before ulceration. The ulceration (Figure 12.6e) is usually associated with some secondary infection and this then leads to the non-specific acute necrotizing cervicitis, as shown in Figure 12.7. Not surprisingly, the stroma is infiltrated with a very dense collection of acute and chronic inflammatory cells that permeate the granulation tissue at the base of the ulcer. The acute inflammatory changes surround the ulcer and generate a marked increase in blood supply; minor trauma to the ulcer commonly produces significant bleeding. The tiny vesicles seen in the initial infection do not last as long on the cervix as on the vulva (1) (Figure 12.8), and they rapidly coalesce, producing the appearance of a single herpetic ulcer. Again, it is important to differentiate this appearance from that of an invasive carcinoma, and at times of doubt it may be necessary, although it is generally not advised, to take a biopsy in order to confirm or refute the diagnosis of invasion. Usually, observation of the lesion over a period of 10–14 days will show the healing changes that occur during this time. It is normally advised not to actively treat the lesions, and, although Zovirax (aciclovir) has been used, it is not so simple to apply to cervical as to vulval or other lesions, and the results have not been consistent. The ulcer heals spontaneously and with minimal residual damage to the cervix, as shown in Figure 12.8 where the healed ulcer is seen at (1). Besides HSV, another cause of necrotizing ulceration is retention of foreign materials, such as tampons and other foreign bodies, in the vagina. Usually, local cleansing will see a rapid healing of such lesions but, once more, differentiation of these lesions from invasive ulcerating carcinomas must be made. Traumatic ulceration and the healing following cervical treatment and biopsy may also give a similar appearance, but can usually be excluded by the history. The vulval lesions caused by herpes can be exquisitely painful and tender (Figure 12.9a,b). The multiple shallow ulcers that coalesce (Figure 12.9b) and develop serpiginous red borders and pale yellow centers are a classic indication of vulval herpes. Extensive involvement with secondary labial edema and tender inguinal lymph glands are associated with this primary lesion. Sometimes there may be less symptomatic lesions that appear more localized (Figure 12.10) and these are frequently seen in recurrent attacks. Figure 12.9 (a,b) The initial stages of the attack are characterized by a prodromal illness that includes malaise, fever, and swelling of the inguinal lymph glands. The vulval lesions are characterized by small vesicles (1), as can be seen in Figure 12.9a. These vesicles very quickly enlarge and become surrounded by an erythematous skin reaction (Figure 12.11). They subsequently rupture and develop into shallow ulcerative lesions that are multiple, painful, and typical of the next stage. Some ulcers within the urethra, or those that are within the vestibule, may cause much distress and even lead to urinary retention. The insertion of a suprapubic catheter in these women is mandatory. The cervix and vagina are also involved in over 50% of cases in which vulval ulcers are seen, and, owing to the lack of free nerve endings in these areas, the condition may be asymptomatic. Differentiation from malignant disease of the vulva can sometimes be difficult to determine. A single large atypical lesion may have the appearance of an early squamous cell carcinoma. Other conditions, such as secondary syphilis and Behçet’s disease, should also be considered (see Figures 9.49, 9.50a). Diagnosis is helped by obtaining smears from the ulcers; Papanicolaou staining will show the characteristic large multinucleate cells. Some will also show emargination of the chromatin and empty nuclei. Viral culture on fibroblasts is the most important diagnostic test. Vesicle fluid or scrapings from an erosion or an acute-phase ulcer provide the best way to procure viral material. It is not possible to culture the virus after the primary lesion has healed and this usually occurs within 2 weeks Serologic tests will also be helpful. They depend on the infected individual developing immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies to HSV2 virus within 21 days of exposure. Approximately 85% of infected persons will develop this antibody in this time. Differentiation between HSV types 1 and 2, which both share 80% of their antigens, is dependent on the IgG and IgM antibodies of the type-specific glycoprotein G-based assay being detected. Approximately 60% of primary genital infections are by HSV type 1 and the remainder by type 2. Indeed, isolation of the virus by culture and smears is most accurate during the first 3 days of infection. When the condition is seen later with the established ulcer, negative results do not rule out herpes and it may be necessary to wait for a further episode before final confirmation can be obtained. At this stage, serologic tests will be helpful. As herpes is a very common sexually transmitted infection, other associated infections, such as syphilis and gonorrhea, must be excluded.

Infective and other conditions causing confusion in diagnosis of lower genital tract precancer

12.1 Introduction

12.2 Trichomonas vaginalis

12.3 Bacterial vaginosis

12.4 Candidiasis

12.5 Herpes genitalis infection

Clinical presentations

Herpes simplex cytology

Colposcopic and histologic appearances of infection

Vulval lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree