12.1 Infectious diseases

Infectious diseases presenting with fever and rash

Infectious diseases of childhood are a significant cause of illness in children, especially in the first years of life. Globally, infection is responsible for the majority of the more than 10 million childhood deaths that occur each year. Many of these infections are preventable by immunization and the high mortality rate is compounded by malnutrition and low birth weight (see Chapter 11.2). In resource-rich countries such as Australia, infectious diseases are the commonest cause of admission to hospital and amongst the commonest reasons for a child to consult a general practitioner. The burden of infectious diseases falls mainly on infants and the preschool child and disproportionately on Indigenous children.

Many infections and related conditions manifest as fever and rash, and a timely and accurate diagnosis is important. This chapter discusses some of the more important and common of these conditions, highlighting the epidemiological and clinical features that may point to a specific diagnosis, as well as the complications, treatment and prevention. Other causes of fever and rash include drug reactions, toxins and autoimmune diseases and these are discussed in related chapters (see Chapters 13 and 21).

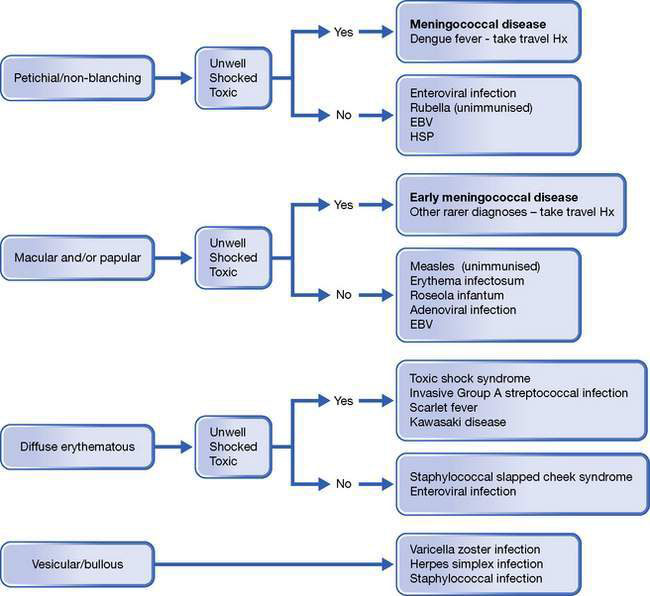

The child with rash and fever needs careful assessment. The most important aspect is identifying potentially life-threatening conditions, of which meningococcal septicaemia (also known as meningococcaemia; see Chapter 12.3) is the most common and important. Meningococcal septicaemia may occur in isolation or together with meningococcal meningitis. It progresses rapidly, has a high mortality, and requires prompt identification and aggressive treatment. Meningococcal disease should be considered in any febrile child with signs of shock even if there is no rash. Other indicators of severe illness include pallor, meningism, abnormal cry, lack of eye contact and failure to respond to normal social clues. Early in the illness, the typical non-blanching rash may be absent in up to a third of cases, may be difficult to find (so undress the child fully and remember to look at the conjunctivae and palate), or initially may be maculopapular with subtle petechial elements. The meningococcus replicates rapidly in the bloodstream and the rash may evolve very quickly. A non-blanching petechial rash is not specific for meningococcal infection; only about 10% of children with a petechial rash have meningococcal disease and the remainder have viral infections, other bacterial infections, or have suffered minor trauma. Early treatment is potentially life-saving; intravenous or intramuscular antibiotics should be given immediately if the diagnosis is suspected and prior to urgent transfer to hospital (Fig. 12.1.1).

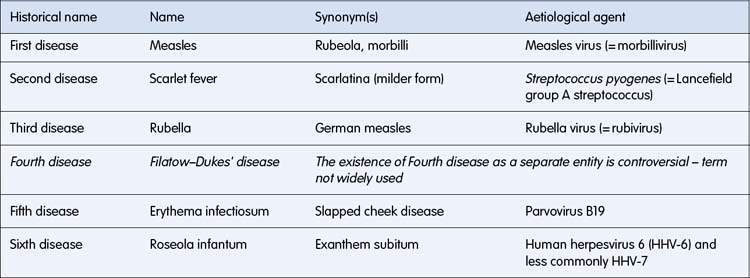

The terminology used to describe infections causing fever and rash can be confusing and some terms are largely of historical interest. An exanthem (from the Greek exanthema, ‘a breaking out’) usually refers to a widespread rash, often of viral origin. An enanthem refers to small spots on the mucous membranes, such as Koplik’s spots seen in measles. In the early 20th century, prior to immunization, six common exanthems of childhood were categorized. Historically these were known as ‘the six diseases of childhood’ (Table 12.1.1). This numerical terminology is still used occasionally, although the existence of the ‘fourth disease’ is questionable.

Measles (rubeola, morbilli)

Epidemiology

• Humans are the only known host.

• Infants and young children are the most susceptible to severe infection.

• Respiratory droplet or airborne spread, highly infectious, causing outbreaks every 2 years in unimmunized populations.

• Incubation period is 8–14 days from the exposure to onset of symptoms.

• Measles is highly contagious and over 98% of adults in unimmunized communities are seropositive.

• Infected individuals are infectious for 4 days before until 4 days after the rash appears (but immunocompromised patients are infectious for the duration of the illness).

• Measles virus may survive in air and on inanimate surfaces for some hours.

• In developing countries, the high mortality rate is due mainly to pneumonia, often with bacterial (staphylococcal or pneumococcal) superinfection.

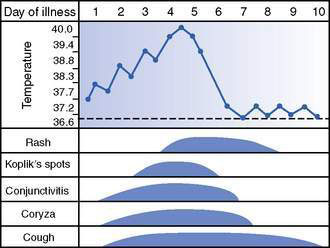

Clinical features (Figs 12.1.2, 12.1.3)

• Prodromal period (symptoms before rash) 3–5 days, with sudden onset of high fever, irritability, brassy or hacking cough, exudative conjunctivitis, rhinorrhoea, otitis media, and a characteristic enanthem on buccal mucosa (Koplik’s spots).

• Rash starts behind ears and spreads caudally. It is a blotchy, raised rash, confluent in places. The more confluent the rash, the more severe the illness.

• Child is miserable and febrile when rash is present but fever resolves rapidly after a few days; persistent fever suggests bacterial superinfection.

• Immunocompromised patients may have minimal rash (showing that T cells are important in the aetiology of measles rash) and may develop fulminant giant cell pneumonia.

Complications

• Acute complications reflect the intense inflammatory response to measles infection, possibly with associated immune suppression.

• Otitis media is the commonest acute complication, followed by lower respiratory tract infection.

• Encephalitis is a rarer but more serious complication, possibly related to the host immune response. It may be fatal (15%) or result in neurological sequelae (25%).

• In resource-poor countries, mastoiditis and diarrhoea are common and life-threatening complications.

• Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a rare (1 in 100 000), devastating, invariably fatal, neurological condition that occurs about 7–8 years after wild-type measles infection (but not vaccination), especially in children infected in infancy. It is characterized by developmental regression with deteriorating intellectual function, seizures, coma and death.

Differential diagnosis

• In roseola infantum (see below) the rash may be identical to measles but appears as the fever subsides, and the child looks well when the rash appears, in contrast to children with measles who are unwell with the rash.

• Other viruses causing morbilliform (measles-like) rash on occasions: enteroviruses, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), adenoviruses, influenza and parainfluenza viruses.

• Antibiotics, especially amoxicillin or ampicillin, may cause a rash, particularly if given to a child with EBV infection.

Prevention

• Measles is a vaccine-preventable disease; it should be possible to eradicate measles from the world by immunization, because humans are the only host.

• Measles vaccine is a live, attenuated vaccine, that can be given alone (monovalent) or in combination with mumps and rubella (MMR) and also varicella vaccines (MMRV). It is not immunogenic if significant maternal measles IgG antibodies are present or if children have received recent intravenous immunoglobulin.

• In Australia, measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccine is given at 1 year of age and a second dose at 4–5 years of age (note that maternal antibody is generally protective before 1 year and interferes with immunogenicity if vaccine is given earlier).

• Live vaccines are generally contraindicated in those with significant immunodeficiency. If exposed to measles, intramuscular or intravenous immunoglobulin gives ‘passive’ protection.

The following are features typical of measles infection:

• Incubation period 8–14 days (1)

• Infectious during the prodromal period, which lasts 3–5 days (2)

• Immunization over 95% protective (3)

• Bronchitis (4), exudative conjunctivitis (5) and otitis media (6) are almost invariable features

• Enanthem called Koplik’s spots (7)

• Rash is classically descending, blotchy to confluent (8), may be papular (raised) and may desquamate, often more marked in children from developing countries (9).

Roseola infantum (exanthem subitum, sixth disease)

Epidemiology

• Caused by infection with human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) and occasionally HHV-7, both DNA viruses.

• Many HHV-6 and HHV-7 infections are asymptomatic or have non-specific symptoms (e.g. fever).

• Mainly affects infants aged 3–18 months.

• Infants usually infected by asymptomatic shedding of virus from family member.

Clinical features and complications

• High fever, irritability, lymphadenopathy, upper respiratory tract signs with inflamed tympanic membranes and diarrhoea are common but non-specific features.

• Morbilliform (measles-like) rash appears as high fever subsides in classical roseola infantum, although pattern is less predictable in many HHV infections.

• Bulging fontanelle and febrile convulsions in acute phase are more common than with other viral infections.

• Virus persists in host (herpesvirus latency) and may reactivate, especially if immunocompromised.

Prevention and treatment

The following are features typical of classical roseola infantum:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree