Infections of the Liver

M. Kyle Jensen and Grzegorz Telega

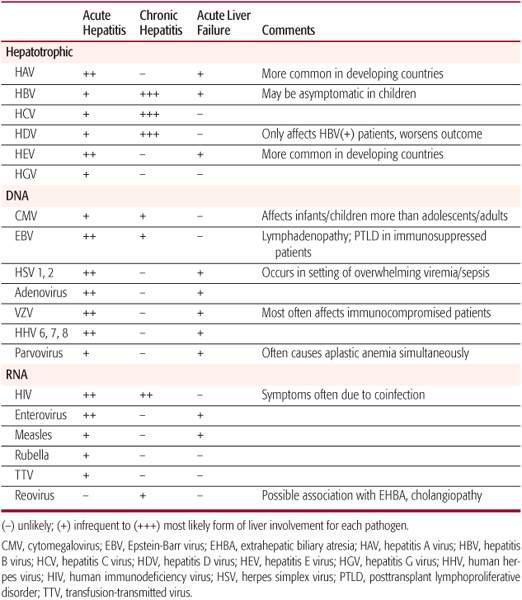

Patients with infections of the liver generally present with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, fatigue, or weight loss. The abdominal pain may be diffuse, be confined to the right upper quadrant, or radiate to the shoulder or back. Other symptoms may include adenopathy, arthralgias, and headache. The initial history should focus on travel, unprotected sex or drug use, anatomical anomalies or surgery that may affect the biliary tracts, a need for hemodialysis or blood products, and family history of hepatitis. Physical exam is often normal; some patients will have right upper quadrant or diffuse abdominal tenderness and hepatomegaly. Jaundice or stigmata of chronic liver disease is infrequent.1 For additional details regarding viral hepatitis, please refer to Table 237-1 and Chapter 308. Details regarding diagnosis and treatment of other organisms that infect the liver are provided in the relevant chapter in Section 17.

Laboratory findings of liver infections often consist of leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) with variable elevation of bilirubin, aminotransferases (ALT/AST), alkaline phosphatase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase. Diagnosis of liver infections requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and should be considered in the context of patient age, chronicity of symptoms, disease epidemiology including geographic location or travel history, and associated conditions such as immune status. Liver ultrasound is useful in initial evaluation of the patient with suspected liver infection because it can screen for liver abscess or bile duct anomalies.

Table 237–1. Common Viral Infections of the Liver and Presentation

BACTERIAL CHOLANGITIS

Cholangitis is an infection of the biliary tracts and is seen most commonly in patients with abnormal biliary tracts such as post-Kasai (portoenterostomy) for biliary atresia. Nearly 60% of patients have one or more episodes of cholangitis after portoenterostomy, with decreasing frequency over time.2 Other conditions that cause functional or mechanical obstruction of the bile ducts such as gallstones, congenital hepatic fibrosis, choledochal cysts, and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) also increase the risk of cholangitis. When these patients present with fever and no obvious other source of infection, they should be evaluated for possible cholangitis. Cholangitis classically presents with jaundice, fever, and right upper quadrant pain (the Charcot triad); however, in children not all symptoms may be present. In patient status post-Kasai, fever is seen in nearly 100% of patients with cholangitis, usually with increased bilirubin or acholic stools and laboratory values showing either leukocytosis or leukopenia.2 Evaluation of cholangitis should include aspartate amino-transferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and blood and urine cultures, although blood cultures will be positive in less than 50% of cases.2-4 Imaging should also be undertaken by either ultrasound or CT scan to rule out the presence of abscess, calculi, ductal dilatation, or other anatomical lesions.3 If concern persists over the presence of a stone, a magnetic resonance cholangiogram (MRI) may be helpful in delineating the location, while endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) provides therapeutic options in cases of obstruction. Liver biopsy can be used to support the diagnosis; however, the diagnostic value of the biopsy should be balanced with the risk of the procedure.

Therapy for cholangitis begins with ensuring that the patient is hemodynamically stable, with fluid resuscitation as needed. The patient may require nasogastric suction if an ileus is present. Antibiotics are given parenterally and should cover the most likely pathogens, based on local sensitivities, and have adequate biliary penetration. Cholangitis is most commonly caused by enteric pathogens such as E coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Enterococcus3; thus antibiotic coverage often involves a cephalosporin or broad-spectrum penicillin such as ampicillinsulbactam in addition to an aminoglycoside. At times coverage should be expanded to include anaerobic bacteria, with a drug such as metro-nidazole. If the patient remains febrile, with evidence of obstruction, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography may be required to relieve the blockage;5 percutaneous drainage or surgical intervention is rarely needed. Patients should demonstrate response with defervescence and corresponding decrease in bilirubin, aminotransferases, and white blood cell count. Treatment should continue for 14 to 21 days.

LIVER ABSCESS

Liver abscesses are usually classified as pyogenic (PLA) or amoebic based on etiology. The distinction is important because treatment varies substantially.

PYOGENIC LIVER ABSCESS

PYOGENIC LIVER ABSCESS

Pyogenic abscesses are commonly associated with trauma to the biliary tract6 or hematogenously spread through the portal vein in conditions such as appendicitis or inflammatory bowel disease.7 Other risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease and altered immune status such as chronic granulomatous disease or leukemia. Important aspects of the patient’s history that suggest amoebic rather than pyogenic abscess include bloody diarrhea or travel to tropical areas preceding the illness. Signs and symptoms are usually nonspecific but commonly include fever, abdominal pain, right upper quadrant tenderness, weight loss, and hepatomegaly. A more fulminant presentation associated with septic shock may occur when multiple abscesses or a ruptured abscess occurs. Laboratory findings often demonstrate leukocytosis and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, but liver enzymes, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin may be normal or only mildly elevated. Diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion and appropriate imaging.

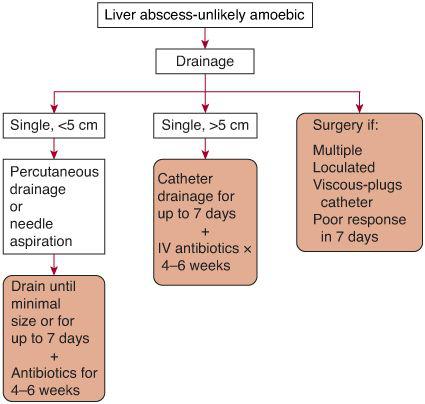

Ultrasound or abdominal CT scans are the first line of imaging and may demonstrate abscesses as small as 1 cm. Abscesses appear as areas of hypoattenuation, with surrounding edema. Pyogenic abscesses are frequently multifocal. A solid appearance should suggest tumor. These findings are enhanced through the use of intravenous contrast. Amoebic abscesses, on the other hand, are usually single, most often in the right lobe, near the diaphragm; these tests, however, do not reliably distinguish between pyogenic abscess and amoebic abscess. As CT scans more accurately delineate abscess size, they allow further therapeutic guidance (see Fig. 237-1). The fluid should be obtained by either needle aspiration or placement of a drainage catheter, with specimens sent for gram stain and culture. Gram-positive bacteria are most common in children, although Gram-negatives and anaerobes are frequently involved and the specimen may grow more than one pathogen. Antibiotic therapy is aimed at covering the most likely pathogens and then refined based on culture susceptibilities. Treatment of 4 to 6 weeks is generally recommended.

AMOEBIC ABSCESS

AMOEBIC ABSCESS

Amoebic abscess presents similarly to pyogenic liver abscess but is caused by Entamoeba histolytica, which is reported to cause hepatic abscesses in up to 7% of invasive cases8 (see Chapter 341). Younger children and those living in or traveling from tropical regions such as Southeast Asia or Central or South America are most commonly affected. Jaundice is infrequently seen and diarrhea may be seen in less than half of patients at the time of presentation; however, a history of dysentery should raise the suspicion for this disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree