Fetal/Neonatal Effects:

Herpes simplex is not teratogenic. Neonatal infection is rare, but has a high mortality. Vertical transmission occurs at vaginal delivery particularly if vesicles are present. This is most likely to follow recent primary maternal infection (risk 40%), because the fetus will not have passive immunity from maternal antibodies.

Diagnosis:

This is usually clear clinically and swabs are of little use in pregnancy.

Management:

Referral to a genitourinary clinic is indicated. Caesarean section is recommended for those delivering within 6 weeks of a primary attack, and those with genital lesions from primary infection at the time of delivery. The risk is very low in women with recurrent herpes who have vesicles present at the time of labour, and caesarean delivery is not recommended. Daily aciclovir in late pregnancy may reduce the frequency of recurrences at term. Exposed neonates are given aciclovir. Screening is of little benefit.

Rubella

Pathology/Epidemiology:

The rubella virus usually affects children and causes a mild febrile illness with a macular rash, which is often called ‘German measles’. Congenital rubella is very rare in UK women because of widespread immunization: <10 affected neonates are born each year (BMJ 1999; 7186: 769). Immunity is lifelong.

Fetal/Neonatal Effects:

Maternal infection in early pregnancy frequently causes multiple fetal abnormalities, including deafness, cardiac disease, eye problems and mental retardation. The probability and severity of malformation decreases with advancing gestation: at 9 weeks the risk is 90%; after 16 weeks, the risk is very low.

Management/Screening:

If a non-immune woman develops rubella before 16 weeks’ gestation, termination of pregnancy is offered. Screening remains routine at booking to identify those in need of vaccination after the end of pregnancy. Rubella vaccine is live and contraindicated in pregnancy, although harm has not been recorded.

Toxoplasmosis

Pathology/Epidemiology:

This is due to the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. It follows contact with cat faeces, or soil, or eating infected meat. In the UK, 20% of adults have antibodies; infection in pregnancy occurs in 0.2% of women in the UK, but it is more common in mainland Europe.

Fetal/Neonatal Effects:

Fetal infection follows in under half: this is more common as pregnancy progresses, but earlier infection is more likely to result in severe sequelae. These include mental retardation, convulsions, spasticities and visual impairment (<10 per year in the UK).

Diagnosis:

Ultrasound may show hydrocephalus, but maternal infection is usually diagnosed after maternal testing for IgM is performed because of exposure or anxiety. False positives and negatives are common. Vertical transmission is diagnosed or excluded using amniocentesis performed after 20 weeks.

Management:

Health education reduces the risk of maternal infection. Spiramycin is started as soon as maternal toxoplasmosis is diagnosed. If vertical transmission is subsequently confirmed, additional combination therapy is also used, though termination may be requested. Whilst this protocol probably improves the prognosis for the neonate, this remains debated. Screening is not recommended where the prevalence is low.

Herpes Zoster

Pathology/Epidemiology:

Primary infection with this DNA herpesvirus causes chickenpox, a common childhood illness; reactivation of latent infection is shingles, which usually affects adults in one or two dermatomes. A woman who is not immune to zoster can develop chickenpox after exposure to chickenpox or shingles. Chickenpox in pregnancy is rare (0.05%), but can cause severe maternal illness.

Fetal/Neonatal Effects:

Teratogenicity is a rare (1–2%) consequence of early pregnancy infection, which is immediately treated with oral aciclovir. Maternal infection in the 4 weeks preceding delivery can cause severe neonatal infection: this is most common (up to 50%) if delivery occurs within 5 days after or 2 days before maternal symptoms.

Management:

Immunoglobulin is used to prevent, and aciclovir to treat infection. Therefore, pregnant women exposed to zoster are tested for immunity: immunoglobulin is recommended if they are non-immune, and aciclovir if infection occurs. In late pregnancy, neonates delivered 5 days after or 2 days before maternal infection are given immunoglobulin, closely monitored and given aciclovir if infection occurs. Vaccination is possible but not universal.

Infections Suitable for Screening

| Syphilis | |

| Hepatitis B | |

| Rubella | |

| Probably: | Chlamydia |

| Bacterial vaginosis | |

| β-haemolytic streptococcus | |

Teratogenic Infections

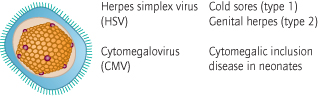

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Rubella

Toxoplasmosis

Syphilis

Herpes zoster (rare)

Parvovirus

Epidemiology:

The B19 virus infects 0.25% of pregnant women, and more during epidemics; 50% of women are immune. A ‘slapped cheek’ appearance (erythema infectiosum) is classic but many have arthralgia or are asymptomatic. Infection is usually from children.

Neonatal/Fetal Effects:

The virus suppresses fetal erythropoiesis causing anaemia. Variable degrees of thrombocytopenia also occur. Fetal death occurs in about 10% of pregnancies, usually with infection before 20 weeks’ gestation.

Diagnosis:

Where maternal exposure or symptoms have occurred, positive maternal IgM testing will prompt fetal surveillance. Anaemia is detectable on ultrasound, initially as increased blood flow velocity in the fetal middle cerebral artery [→ p.200] and subsequently as oedema (fetal hydrops [→ p.160]) from cardiac failure. Or maternal testing may follow the identification of fetal hydrops. Spontaneous resolution of anaemia and hydrops occurs in about 50%.

Management:

Mothers infected are scanned regularly to look for anaemia. Where hydrops is detected, in utero transfusion is given if this is severe. Survivors have an excellent prognosis although very severe disease has recently been associated with neurological damage (Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109: 42).

Group B Streptococcus

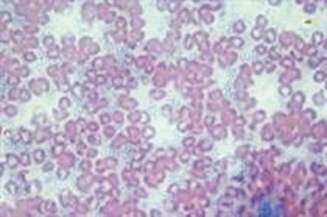

Pathology/Epidemiology:

The bacterium Streptococcus agalactiae (Fig. 19.3) is carried, without symptoms, by about 25% of pregnant women.

Neonatal Effects:

The fetus can be infected, normally during labour after the membranes have ruptured. This is most common with preterm labours, if labour is prolonged or there is a maternal fever. Early onset neonatal group B streptococcus (GBS) sepsis [→ p.252] occurs in 1 in 500 neonates. It causes severe illness and has a mortality of 6% in term infants and 18% in preterm infants. Vertical transmission can be mostly prevented by intravenous penicillin.

Management/Screening:

Policies differ in different countries: in the US (Strategy 2) universal screening is recommended; in the UK, currently, it is not. In the UK, treatment is used merely if risk factors for vertical transmission of GBS are present, or if GBS is found incidentally (Strategy 1).

Strategy 1: Current UK practice is under scrutiny and differs widely. Screening has hitherto not been recommended because of fears of anaphylaxis, and possibly cost and medicalization of labour. Treatment is usually restricted to those with risk factors: a previous affected neonate, positive urinary culture for GBS, preterm labour, rupture of the membranes for >18 h and a maternal fever in labour. In addition, treatment is usual for incidental GBS carriage.

Strategy 2: Screening is the most effective practice, reducing early onset neonatal GBS sepsis by about 80%. Cultures from both vagina and anus are taken at 35–37 weeks. Culture-positive women are given intravenous antibiotics, usually penicillin at high dose, throughout labour. Antibiotics are also given to those who have a positive urine culture for GBS, those with an infant previously affected by GBS, and those who develop clinical risk factors (see below) for GBS disease.

Prevention of Vertical Transmission of Group B Streptococcus

| Strategy 1: Risk factors | No screening |