Induced Abortion

Sabrina Holmquist

Melissa Gilliam

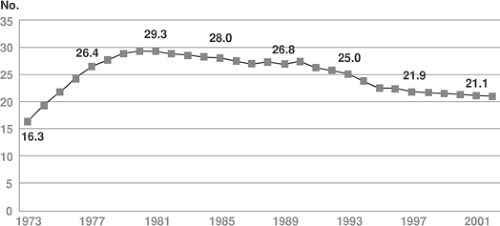

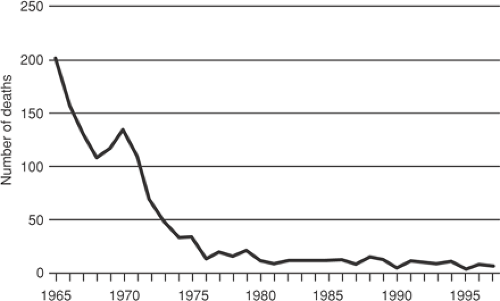

Recent estimates find that approximately 1.29 million abortions were performed in the United States in 2003, a 2% decrease from 1.31 million in 2000. Each year in the United States, 2% of women of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) terminate a pregnancy legally. Given the current rate, it is estimated that over one third of women in the United States will have had an abortion by age 45. The abortion rate in 2000 was about 21.3 per 1,000 women. This rate has decreased from 27.4 abortions per 1,000 women in 1990 (Fig. 33.1). While nearly all women in the United States have used some form of contraceptive at some point in their lives and contraceptive use has increased considerably since the legalization of abortion, about half of the 6 million pregnancies occurring each year are reportedly unplanned. Roughly half of these unplanned pregnancies, one in five pregnancies overall, are terminated by induced abortion. Women who opt for abortion tend to be never married, in their 20s, live below the federal poverty level, and are mothers of at least one child. Over half of women who have had an abortion used some form of contraception during the month that they became pregnant. Since legalization in 1973, abortion in the United States has become very safe (Fig. 33.2). Yet, worldwide, 19 of the 46 million abortions performed annually are done so illegally. Illegal abortion remains very unsafe and account for some 68,000 deaths globally each year.

Legalization

The landmark 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade effectively legalized abortion in the United States. Since that time, federal and state legislators have proposed or enacted hundreds of pieces of legislation aimed at restricting access to abortion or challenging the Court’s Roe decision, making induced abortion the most actively litigated and highly publicized area in medicine. As early as 1976, the Hyde Amendment prohibited the use of federal Medicaid funding for abortions. In 1992, the Supreme Court’s decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey reaffirmed a woman’s right to an abortion “before viability” but at the same time opened the door for states to impose additional restrictions that would not impose an “undue burden” on the woman.

Antiabortion legislation seeks to chip away at access to abortion through a variety of means. The federal so-called “partial-birth abortion” ban of 2003 attempted to abolish certain late-second-trimester abortion procedures, but due to its vague language, it could have further reaching effects; at the time of this writing, a Supreme Court case challenging the ban awaits a decision. A number of states have mandated parental notification or consent before a minor is able to obtain an abortion. In some states, women seeking abortions must undergo a waiting period of at least 24 hours or receive state-sanctioned counseling beforehand; in some cases, this counseling contains ideologically charged or scientifically disputed information that is meant to discourage women from ultimately choosing abortion. A handful of states, most notably South Dakota in 2006, have attempted to pass bans on almost all abortions with the express purpose of challenging Roe.

Abortion Counseling

Pregnancy options counseling is an essential element of abortion provision, whether in a dedicated abortion clinic, a private office, or an inpatient setting. This type of counseling has three primary goals: helping the patient make an informed decision about her pregnancy, increasing the patient’s knowledge and comfort with the abortion procedure, and alleviating anxiety and pain during the procedure while providing emotional support for her decision. Pregnancy options counseling can be performed by nursing staff, physicians, or dedicated counselors but is most effective when performed by an experienced options counselor

with knowledge of local laws governing consent procedures and state-mandated counseling requirements.

with knowledge of local laws governing consent procedures and state-mandated counseling requirements.

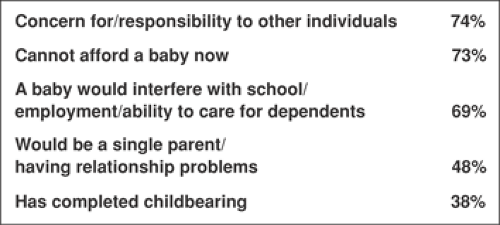

Preprocedure counseling has two primary components: pregnancy options counseling and decision making and preprocedure counseling and informed consent for women who choose to have an abortion. The initial part of the counseling session should center on exploring feelings about the pregnancy, including when and under what circumstances the patient became pregnant, how she feels about that pregnancy, and what options she has considered regarding its outcome. Women choose to have an abortion for a variety of reasons (Fig. 33.3) and have a wide variety of emotional responses to unplanned pregnancy, ranging from acceptance to ambivalence to anger, shame, and fear. Maintaining an open, nonjudgmental atmosphere is essential in allowing women to explore their feelings regarding their pregnancy and options that are open to them. The full range of pregnancy options should be discussed, including parenting, adoption, and abortion. Women should be encouraged to consider how each of these options would impact her life personally, financially, and emotionally as well as how they mesh with her values and those of her partner and family, if applicable. Any misconceptions regarding pregnancy options should be corrected, and the provider should assure that she is not being coerced into a decision.

For women who choose abortion as their best option, the next step is helping them select an appropriate procedure. Before 9 weeks gestation, women can choose a medication or surgical abortion. Medication abortion is a process by which a pregnancy is terminated by use of medication without surgical intervention. It generally requires two visits, and patients must be willing to administer medication at home and be prepared for cramping, bleeding, and passage of tissue outside of a medical setting. For women without contraindications to medication abortion (allergy to mifepristone or misoprostol, bleeding dyscrasias, severe anemia) who are able to come for one follow-up visit, medication abortion provides a nonsurgical alternative to traditional dilation and curettage (D&C). For women who choose a surgical procedure, there are two options for first-trimester abortion: manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) and suction D&C. The characteristics of each of these modalities are listed in Table 33.1. Acceptability studies reveal that patients are highly satisfied with any of these procedures as long as they are able to make their own choice. The specifics of each procedure are covered in subsequent sections of this chapter as well as

informed consent for each. Women presenting after the first trimester also have the option of undergoing a medication or surgical procedure; these procedures are discussed in subsequent sections.

informed consent for each. Women presenting after the first trimester also have the option of undergoing a medication or surgical procedure; these procedures are discussed in subsequent sections.

Preprocedure Assessment

Prior to providing an abortion procedure, whether medication or surgical, each patient requires a preoperative assessment. Obstetric, medical, and surgical history should be recorded, emphasizing sexually transmitted disease history, contraception, menstrual history, the outcomes of previous pregnancies, previous uterine or cervical surgery, and any medication allergies. Previous anesthetic complications, bleeding problems, or transfusions also should be noted. Special attention should be paid to any conditions that may affect minor surgical procedures, including asthma, current medications, alcohol or drug abuse, chronic steroid use, HIV disease, coagulopathies, heart disease, or seizure disorders. Vital signs as well as a brief heart, lung, abdominal and thorough pelvic exam should be performed, including ascertainment of uterine size and position and abnormal or mucopurulent cervicovaginal discharge. Screening for cervical gonorrhea and chlamydial organisms prior to performing an abortion procedure can be employed universally, in at-risk patients only (based on clinical history and risk factors), or not at all depending on the practice setting. Because untreated chlamydial infection at the time of a transcervical procedure is associated with a 19% rate of postoperative salpingitis, prophylactic periabortal antibiotics should be administered to all patients regardless of preprocedure cervical screening. While Pap testing can be done for women who are due for their annual screening, it is not a necessary part of abortion care.

TABLE 33.1 Characteristics of Medication and Surgical Abortion in the First Trimester | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Accurate estimation of gestational age is key to both procedure selection and ascertainment of surgical risk; incorrect estimation of gestational age is an important cause of abortion complications. In the absence of a certain last menstrual period and clinical correlation of uterine size by an experienced provider, ultrasound examination is a highly accurate way of confirming and dating an intrauterine pregnancy as well as a means for ruling out an ectopic or anembryonic gestation. In the absence of an intrauterine gestation, comprehensive pelvic ultrasound and serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) testing should be employed to locate the pregnancy prior to attempted termination either by medication or surgical means. If the patient is too early in gestation to detect a gestational sac, the procedure should be delayed until a sac is visible. Absolute hCG levels at which an intrauterine gestation should be visible vary depending on ultrasound resolution and the skill of the sonographer; however, a hCG discriminatory threshold of 1,500 mIU/mL typically is accompanied by a gestational sac detectable by transvaginal ultrasound. Laboratory tests should include Rh(D) typing, with administration of Rh immune globulin to Rh-negative patients immediately after their procedure as well as hemoglobin/hematocrit to assess for anemia.

Most generally healthy women can safely obtain abortion procedures in the outpatient setting. Patients with severe medical or psychiatric conditions requiring intraoperative monitoring as well as those with pregnancy complications requiring pre- or postoperative monitoring or administration of intravenous antibiotics are best served in the inpatient operative setting. Induction termination procedures generally are performed in a hospital setting.

Surgical Abortion in the First Trimester

Surgical abortion in the first trimester can be performed between approximately 5 and 13 completed weeks gestation (depending on when an intrauterine sac is visible). Considered the gold standard for pregnancy termination,

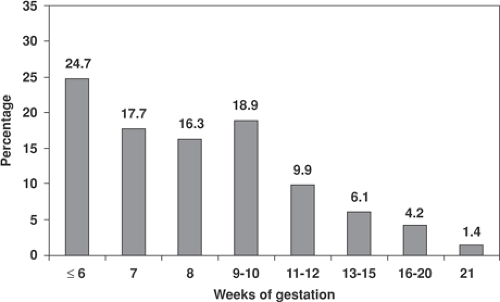

a first-trimester surgical procedure is very effective (99.0% efficacy rate), very safe (major complication rate of 0.5%), and very common—89.0% of abortions provided in the United States occur before 13 completed weeks gestation; more than half occur before 8 weeks (Fig. 33.4). The D&C procedure includes both dilation of the cervix, which can be achieved chemically, mechanically, or a combination of the two, and emptying of the uterine contents, which is most commonly achieved by suction curettage either by using a traditional electric suction aspirator or via MVA.

a first-trimester surgical procedure is very effective (99.0% efficacy rate), very safe (major complication rate of 0.5%), and very common—89.0% of abortions provided in the United States occur before 13 completed weeks gestation; more than half occur before 8 weeks (Fig. 33.4). The D&C procedure includes both dilation of the cervix, which can be achieved chemically, mechanically, or a combination of the two, and emptying of the uterine contents, which is most commonly achieved by suction curettage either by using a traditional electric suction aspirator or via MVA.

Anesthesia for first-trimester procedures typically is achieved by using deep paracervical infiltration with lidocaine—6 cc at the 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions, respectively, in tandem with oral analgesics such as ibuprofen (400 to 800 mg) and an oral anxiolytic, usually a benzodiazepine such as lorazepam 1 to 2 mg. A support person to calm and help focus the patient during the procedure is another vital component to providing comfortable procedures under local anesthesia. Approximately 58% of women receive only local anesthesia for early surgical abortion. Many providers also offer the option of light to moderate intravenous sedation, typically employing a short-acting anxiolytic such as midazolam and a short-acting narcotic such as fentanyl. Preoperative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often employed as well. Satisfaction surveys reveal that patients are highly satisfied with either anesthesia option as long as they are given a choice. Providers who wish to offer conscious sedation must have appropriate perioperative monitoring equipment available, including pulse oximetry, a continuous supply of oxygen, reversing medications, and resuscitation equipment, as well as adequate staff to provide postoperative monitoring.

Cervical Dilation

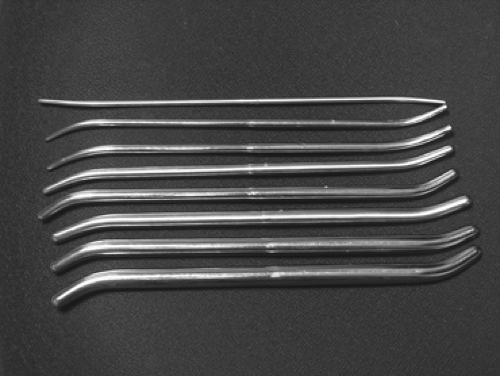

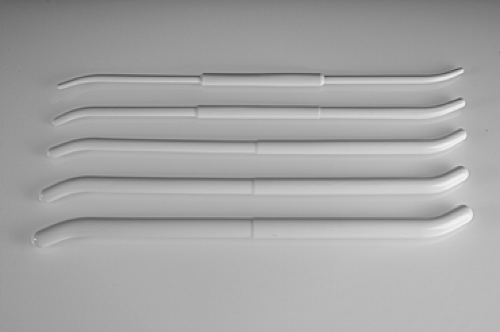

Cervical dilation is one of the most important aspects of abortion care, as it confers safety to the procedure. Inadequate or forced dilation is the primary cause of surgical complications in the first trimester. Dilation can be achieved chemically with the use of cervical ripening agents such as misoprostol or mechanically by using rigid cervical dilators. A mixed approach is employed most often, particularly after 10 weeks gestation. Mechanical dilation is accomplished with progressive use of graduated cervical dilators to serially enlarge the cervical canal; tapered dilators such as the Pratt (Fig. 33.5) or Denniston (Fig. 33.6) are easiest to pass through the internal cervical os. After administration of local anesthetic, the provider should don sterile gloves; grasp the anterior lip of the cervix with a single-tooth tenaculum, ring forceps or similar stabilizing instrument; and gently and progressively dilate the cervix to a diameter roughly equal to the gestational age in weeks (i.e., an 8-week pregnancy should be dilated to 8 mm, or 23 to 25 French. To decrease the risk of infection, particularly in a nonsterile environment, a “no-touch” technique is employed by which no part of an instrument that enters the uterine cavity is touched by the provider during the dilation process. This includes both mechanical dilator tips and the suction cannula. Use of a uterine sound to measure uterine

size prior to dilation is discouraged, as uterine size can be estimated in other ways and the uterine sound is the most common instrument responsible for uterine perforation.

size prior to dilation is discouraged, as uterine size can be estimated in other ways and the uterine sound is the most common instrument responsible for uterine perforation.

Figure 33.5 Pratt dilators. (From MedGyn website. Available at: http://www.medgyn.com/picprattdilator.htm.) |

Figure 33.6 Denniston dilators. (From Ipas website. Available at: http://www.ipas.org/products/Ipas_Denniston_Dilators.aspx.) |

Mechanical dilation should never be forced. If a dilator does not pass easily, allow the dilator that is one size smaller to remain in the cervix for a few minutes before advancing the next. Forcing mechanical dilation can lead to cervical fracture, uterine perforation, or creation of a false passage within the cervix. Ultrasound guidance can be employed in patients with a tortuous cervical canal or other anatomic abnormality. For nulliparous patients or those with cervical stenosis or higher gestational ages, preoperative misoprostol can be used from 20 minutes to 24 hours prior to the procedure. Patients can be given a low (200 to 400 mcg) dose orally the night before the procedure; alternately, 400 to 800 mcg of misoprostol can be administered vaginally 40- to 90-minutes preprocedure or 400 mcg buccally or sublingually 20 to 40 minutes prior. Some providers use premedication with misoprostol with all patients regardless of gestational age to aid with speed and comfort of dilation. Many patients at <8 weeks gestation may require no mechanical dilation at all following misoprostol administration. However, patients given a preoperative dose the night before their procedure should be aware that misoprostol causes uterine activity that could result in bleeding and possible expulsion of the pregnancy at home.

Suction Aspiration

Once the cervix has been adequately dilated, a suction cannula is advanced gently to the uterine fundus. Suction cannulas range in size from 5 to 16 mm (corresponding to their diameter in millimeters); the cannula should be roughly equal in diameter to the gestational age (i.e., an 8-week pregnancy is most easily evacuated with a no. 8 suction cannula). Suction can then be generated either with a mechanical suction aspirator or traditional electric suction aspirator. Both techniques are equally safe and efficacious; MVA confers the extra benefits of being portable, not requiring electricity, and eliminating the expense and noise of a traditional electric aspiration machine. Equal and high patient satisfaction has been documented for both techniques.

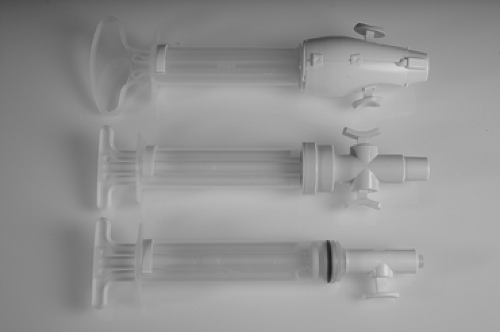

A mechanical vacuum aspirator consists of a 60-cc locking syringe with a single or double value system that generates approximately 60 to 70 mm Hg of pressure (equivalent to an electric suction aspirator). This handheld device, which may be disposable or reusable depending on the manufacturer, is attached to a flexible suction cannula. The cannula is introduced into the uterine cavity to the fundus by using a no-touch technique. Suction is then activated by release of the double-valve system (Fig. 33.7) or pulling back on the plunger, and the entire syringe unit is rotated, shearing the products of conception from the walls of the uterus and into the collection syringe. A gentle curetting motion also can be employed, with careful attention to not advancing the cannula past the posterior uterine wall or fundus. Complete emptying is detected by cessation of the flow of tissue into the syringe and the characteristic gritty texture palpated in all four quadrants of the uterine cavity. Loss of suction can occur due to a clogged cannula or a full syringe; the cannula may be removed and unblocked and the syringe emptied and reloaded. This procedure may be repeated until the uterus is completely evacuated. MVA is most often employed before 9 weeks gestation (as more advanced gestations require serial emptying and reloading of the syringe) but can be used for later gestations, including dilation and evacuation (D&E) up to 16 weeks gestation.

For gestations >8–9 weeks, many providers prefer electric suction aspiration, which has the advantage of providing continuous suction without reloading of the collection chamber and more commonly employs rigid suction cannulas (Fig. 33.8). Larger tubing and cannulas that are up to 16 mm in diameter also can be employed. Rigid suction cannulas may be straight or curved; a curved cannula will conform more anatomically with the position of the uterus and consequently may be easier to pass to the fundus. The technique for electric suction aspiration is

identical to MVA; signs of complete uterine evacuation include bubbles in the suction tubing and the characteristic gritty texture of the empty uterine cavity.

identical to MVA; signs of complete uterine evacuation include bubbles in the suction tubing and the characteristic gritty texture of the empty uterine cavity.

Figure 33.7 MVA Plus mechanical vacuum aspirator. (From Ipas website: Available at: http://www.ipas.org/products/Ipas_MVA_Plus_Aspirator.aspx?ht) |

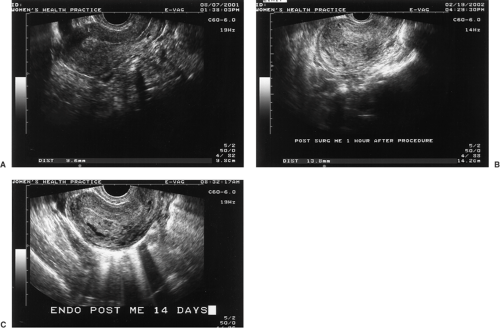

Meticulous examination of the uterine aspirate is essential in confirming complete uterine emptying. The uterine aspirate can be washed with water or saline and examined with backlighting though a clear receptacle (such as a glass pie plate and a light box) (Fig. 33.9). Identification of the gestational sac in early pregnancy is essential in preventing an incomplete or failed procedure. At later gestational ages, all fetal parts should be identified. If there is any question regarding completeness of the procedure, transvaginal ultrasound can be performed to confirm and document complete uterine emptying (Fig. 33.10).

Pathologic examination of tissue is indicated for suspected abnormal pregnancies (i.e., hydatidiform mole), and cytogenetic examination can be employed in the cases of miscarriage or known or suspected genetic abnormality. Otherwise, pathologic confirmation is not mandatory, provided all products of conception are examined and villi identified. Blood loss should be minimal, at 15 to 30 cc. Aftercare should include perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis as detailed previously, NSAIDs for analgesia, and commencement of a contraceptive method before resuming sexual activity. Placement of an intrauterine device (IUD) immediately after first-trimester surgical termination is safe and convenient and has not been associated with an increased rate of expulsion. Cervical cultures should be obtained in all patients who are planning to receive a postabortal IUD.

Pathologic examination of tissue is indicated for suspected abnormal pregnancies (i.e., hydatidiform mole), and cytogenetic examination can be employed in the cases of miscarriage or known or suspected genetic abnormality. Otherwise, pathologic confirmation is not mandatory, provided all products of conception are examined and villi identified. Blood loss should be minimal, at 15 to 30 cc. Aftercare should include perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis as detailed previously, NSAIDs for analgesia, and commencement of a contraceptive method before resuming sexual activity. Placement of an intrauterine device (IUD) immediately after first-trimester surgical termination is safe and convenient and has not been associated with an increased rate of expulsion. Cervical cultures should be obtained in all patients who are planning to receive a postabortal IUD.

Figure 33.9 Transillumination of villi floating in saline allows visualization for placental tissue confirmation after pregnancy termination. |

Second-trimester Abortion

Approximately 12% of abortions performed in the United States occur after 12 completed weeks gestation. More than 95% of these are performed surgically by D&E. More second-trimester abortion procedures are performed in the United States than in any other country worldwide, which likely is due to the higher abortion numbers in the United States overall, better record keeping, and the relative delay in accessing services in the United States in comparison to countries with socialized medicine where abortion care is widely available and provided under national health care policies (Table 33.2). Abortion after the first trimester is a riskier procedure than earlier procedures; while the major complication rate is still <1%, the overall risk of mortality is ten times that of suction D&C in the first trimester.

Dilation and Evacuation

D&E is the most common method of second-trimester abortion. Dilation in the second trimester is both more involved and extremely important, as the cervix must be dilated to a sufficient diameter to allow a larger fetus to be removed safely without trauma to the cervical canal or uterus while still maintaining adequate cervical patency to carry a future pregnancy to term. This is achieved with osmotic dilators and often augmented with pharmacologic

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree