Materials and Methods

Study setting

The current study was conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, which is a tertiary-care academic medical center. The depression screening program was implemented within the 2 largest outpatient obstetrics sites in July 2010. The current study uses data during the consequent 4 years after implementation of routine screening for depression from July 2010 through June 2014. This study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board.

Study intervention

The goal of the peripartum depression screening and linkage program was to operate within the context of existing clinical resources to minimize the impact on provider and patient clinical flow. In 2010, the state of Massachusetts mandated that providers and insurance carriers report the number of women who were screened for depression up to 6 months postpartum on an annual basis ; however, providers and institutions were given clinical discretion regarding how and when to perform screening and what follow-up care to provide. Clinical staff and mental health providers who were involved in depression screening were not mandated by the state nor were they state funded. In response to the state mandate, our institution implemented a screening program that uses the EPDS both early in the third trimester (generally at 24-28 weeks of gestation) and again in the postpartum period (generally at the 6-week postpartum visit). The current analysis was undertaken, given concerns about the feasibility of universal screening, which included patient willingness to complete the form as part of routine obstetric care and real-time scoring and entry of the EPDS into the electronic medical record (EMR).

The EPDS, a 10-item questionnaire, has established psychometric properties and is 1 of the most widely used self-reported instruments to assess depressive symptoms in pregnant and postpartum women, which includes minorities and teenagers. The cutoff point that is used to identify women as high-risk for postpartum depression varies, with most studies using a cutoff score of ≥10 or ≥12. The current study used an EPDS cut-off of ≥12 to screen positive for depression.

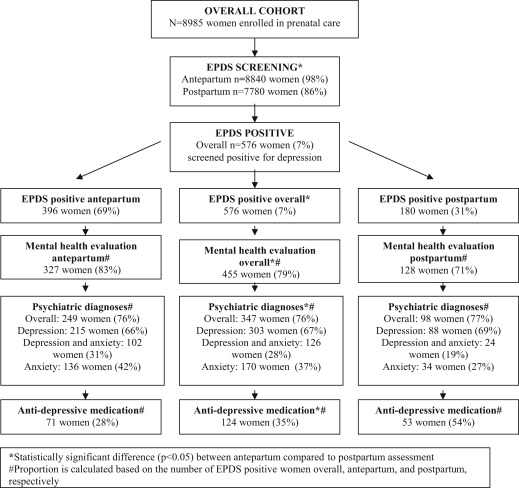

The Figure displays a flow chart that shows how women were screened, referred, and treated initially for depression in a similar manner during both the antepartum and the postpartum periods. At the time of initial obstetric intake by phone, clinic nurses asked patients if they had a history of depression and a current psychiatric diagnosis as part of their intake medical history. During antepartum and postpartum screening, the EPDS score was tabulated in real time and entered in her EMR as a total score at the time of the 24- and 28-week antepartum and 6-week postpartum visits for all women, regardless of their EPDS score. All women with an EPDS score of ≥12 were offered a prompt referral either by a licensed clinical social worker at the same clinic visit or by telephone for women who could not be triaged at their obstetric visit to an onsite mental health evaluation, which was documented in the EMR as a separate encounter note. Licensed clinical social workers who were already on staff in the obstetrics clinic were responsible for evaluating screen-positive patients and for triaging mental health referrals. Based on this initial triage (at which time a patient’s psychiatric history, current psychiatric symptoms, and goals of care were elicited), the social worker then coordinated an appointment for a mental health evaluation with a licensed social worker, a clinical psychologist, or a psychiatrist. All women who screened positive for depression had depression added to their obstetric problem list, which could be viewed by all obstetric and mental health providers in the EMR. Women who screened positive for depression before delivery were offered a 2-week postpartum visit before the standard 6-week postpartum visit that was offered to other patients.

Study variables

Data were abstracted from the EMR, which documented EPDS scores at 24-28 weeks of gestation and 6 weeks postpartum. Additional demographic and clinical data were abstracted from the maternal obstetrics EMR and included age, race, household zip code, enrollment in state public health insurance, parity, prepregnancy body mass index, and tobacco use during pregnancy. Median household income was imputed with the use of 2013 US Census Bureau data for the patient’s residential zip code. Information about referral and consequent mental health evaluation and treatment was reviewed by 2 study authors (KKV and AJK) for all women who screened positive for depression. At the time of initial mental health referral, patients who did not follow up with mental health services were categorized as either those women who declined a mental health consultation or those who transferred obstetric care. Linkage to mental health care was defined as a mental health consultation within 8 weeks of the initial referral that was documented in the EMR, which included both in-network mental health evaluations and documentation of outside mental heath providers in obstetric provider evaluations. The following psychiatric variables were abstracted from mental health evaluations in the EMR: diagnosis of major depression and/or anxiety disorder, history of a diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression, and initiation of an antidepressant medication.

Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics for the study population of women who screened positive for depression (ie, EPDS cut-off, ≥12) overall and then separately the antepartum period relative to the postpartum period. Although the goal was for all women to be screened during both the antepartum and the postpartum periods, regardless of screening positive before delivery, we did not include women who screened positive before delivery among the women who screened positive postpartum in the current analysis because they were considered already to have a positive depression screen. We compared sociodemographic, clinical, and psychiatric characteristics of women who screened positive for depression before delivery relative with postpartum using chi-square and the Student t test. Logistic regression models with adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were calculated for predictors of linking to mental health services after screening positive for depression and controlling for time of screening positive (antepartum vs postpartum periods), maternal age, parity, maternal race, and imputed median household income. All analyses used STATA software (version 10.0; STATA Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Among 8985 women who were enrolled in prenatal care at the participating clinical sites during the study period from July 2010 through June 2014, 8840 women (98%) had complete antepartum EPDS screening results, and 7780 women (86%) were screened postpartum.

Overall, 576 women (7%) screened positive for depression (ie, EPDS, ≥12; Figure ). The mean EPDS score for women who screened positive was 14.7. The mean age was 35.7 years; 52% of the women were white, and 49% of the women were multiparous. One-tenth of the women (10%) delivered preterm at <37 weeks of gestation. A total of 396 women (69%) screened positive before delivery, compared with 180 women (31%) postpartum, and 48 women (8%) screened positive during both the antepartum and the postpartum periods ( Table 1 ). Women who screened positive for depression before delivery were significantly more likely to be younger in age, parous, Latina or black, of lower household income, and enrolled in a public insurance program, compared with women who screened positive postpartum ( P < .05).

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 576), n (%) | Antepartum and postpartum periods (n = 48), n (%) | Antepartum period (n = 396), n (%) | Postpartum period (n = 180), n (%) | P value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at delivery, y | .01 | ||||

| <30 | 163 (28.3) | 12 (25.0) | 126 (31.8) | 37 (20.6) | |

| 30-35 | 206 (35.8) | 22 (45.8) | 138 (34.9) | 68 (37.8) | |

| >35 | 207 (35.9) | 14 (29.2) | 132 (33.3) | 75 (41.7) | |

| Parity b | .005 | ||||

| 0 | 293 (51.1) | 21 (43.8) | 186 (47.2) | 107 (59.8) | |

| 1+ | 280 (48.9) | 27 (56.3) | 208 (52.8) | 72 (40.2) | |

| Self-identified race/ethnicity | .01 | ||||

| White | 301 (52.3) | 25 (52.1) | 200 (50.5) | 101 (56.1) | |

| Black | 56 (9.7) | 6 (12.5) | 42 (10.6) | 14 (7.8) | |

| Latina | 38 (6.6) | 4 (8.3) | 32 (8.1) | 6 (3.3) | |

| Asian | 48 (8.3) | 3 (6.3) | 25 (6.3) | 23 (12.8) | |

| Other/unknown | 133 (23.1) | 10 (20.8) | 97 (24.5) | 36 (20.0) | |

| Median imputed household income b | .04 | ||||

| 1st Quartile (<$51,863) | 154 (26.8) | 17 (35.4) | 116 (29.4) | 38 (21.1) | |

| 2nd–3rd Quartile ($51,864-87,225) | 279 (48.6) | 23 (47.9) | 191 (48.5) | 88 (48.9) | |

| 4th Quartile (>$87,226) | 141 (24.6) | 8 (16.7) | 87 (22.1) | 54 (30.0) | |

| Enrolled in state public insurance program | 153 (26.6) | 122 (30.8) | 31 (17.2) | .001 | |

| First-trimester body mass index, kg/m 2 b | .12 | ||||

| <25 | 295 (54.6) | 22 (45.8) | 189 (51.8) | 106 (60.6) | |

| 25-30 | 140 (25.9) | 12 (25.0) | 103 (28.2) | 37 (21.1) | |

| >30 | 105 (19.4) | 14 (29.2) | 73 (20.0) | 32 (18.3) | |

| Tobacco use during pregnancy | 32 (5.6) | 2 (4.2) | 25 (6.3) | 7 (3.9) | .23 |

| Gestational age at delivery, wk b | .55 | ||||

| <37 | 51 (9.5) | 1 (2.1) | 37 (10.3) | 14 (7.9) | |

| 37-39 | 227 (42.1) | 24 (50.0) | 154 (42.7) | 73 (41.0) | |

| >39 | 261 (48.4) | 23 (47.9) | 170 (47.1) | 91 (51.1) |

a Statistically significant finding: P < .05

b Missing data on 3 women for parity, 2 women for household income, 6 women for body mass index, and 7 women for gestational age at delivery.

After initial triage with a clinic social worker, more than three-fourths of women (79%) who screened positive received an initial formal mental health evaluation, which was significantly more common before delivery compared with postpartum (83% vs 71%; P = .002; Table 2 ). A total of 121 women (21%) were not linked to mental health services, and the primary reasons for no follow-up evaluation were (1) declining a referral (30%) and (2) transferring obstetric care (12%).

| Psychiatric characteristics | Overall (n = 576) | Antepartum period (n = 396) | Postpartum period (n = 180), n (%) | P value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage to mental health services, n (%) | 455 (78.9) | 327 (82.5) | 128 (71.1) | .002 |

| Reasons for no linkage to mental health services (n = 121), n (%) | <.0001 | |||

| Transferred obstetric care | 14 (11.6) | 14 (20.3) | — | |

| Declined evaluation | 36 (29.8) | 8 (11.6) | 28 (53.9) | |

| No follow-up | 71 (58.7) | 47 (68.1) | 24 (46.2) | |

| Mean Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score, ± SD | 14.7 ± 2.95 | 14.7 ± 2.96 | 14.6 ± 2.93 | .78 |

| Evaluated by mental health services, n (%) | .002 | |||

| Psychiatrist only | 35 (6.1) | 19 (4.8) | 16 (8.9) | |

| Social worker/psychologist only | 269 (46.7) | 196 (49.5) | 73 (40.6) | |

| Both | 151 (26.2) | 112 (28.3) | 39 (21.7) | |

| Not linked to mental health services | 121 (21.1) | 69 (17.4) | 52 (28.9) | |

| History of diagnosis of depression and/or anxiety, n (%) | 201 (35.0) | 170 (43.1) | 31 (17.2) | <.0001 |

| Psychiatric diagnoses, n (%) | ||||

| Overall among screen positive women (n = 576), not mutually exclusive | ||||

| Depression or anxiety | 357 (62.0) | 258 (65.2) | 99 (55.0) | .02 |

| Depression | 307 (53.3) | 219 (55.3) | 88 (48.9) | .15 |

| Anxiety | 177 (30.7) | 142 (35.9) | 35 (19.4) | <.0001 |

| Both depression and anxiety | 126 (22.1) | 102 (26.0) | 24 (13.3) | .001 |

| Among women who linked to mental health services (n = 455), mutually exclusive | .01 | |||

| Depression only | 177 (38.9) | 113 (34.6) | 64 (50.0) | |

| Anxiety only | 44 (9.7) | 34 (10.4) | 10 (7.8) | |

| Both depression and anxiety | 126 (27.7) | 102 (31.2) | 24 (18.8) | |

| Other | 108 (23.7) | 78 (23.9) | 30 (23.4) | |

| Not mutually exclusive | ||||

| Depression or anxiety | 347 (76.2) | 249 (76.1) | 98 (76.6) | |

| Depression | 303 (66.6) | 215 (65.7) | 88 (68.8) | |

| Anxiety | 170 (37.4) | 136 (41.6) | 34 (26.6) | |

| Both depression and anxiety | 126 (27.6) | 102 (31.2) | 24 (18.8) | |

| Antidepressant medication initiation overall, n (%) | 124 (27.8) | 71 (22.7) | 53 (40.2) | <.0001 |

| Initiated antidepressant medication among women who were diagnosed with anxiety/depression (n = 358), n (%) | 125 (34.9) | 72 (27.8) | 53 (53.5) | <.0001 |

| Postpartum care: no postpartum visit, % | 12.1 | 19.1 | — | — |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree