7.1 Imaging

Introduction

Radiation protection is provided by the following measures:

1. Limiting examinations to those that are likely to provide diagnostic help and influence treatment decisions

2. Using optimal technical factors in order to provide the lowest dose of X-rays for a diagnostic study

3. Limiting fluoroscopic time and using ‘last image hold’ techniques when possible

Every person is exposed to background radiation from the world around them and from cosmic rays. Radon gas provides the major source of background dose. Total annual background dose, per person, therefore depends heavily on the geographical location, and is estimated to be 2–3 mSv (Table 7.1.1). This does not include medical exposure, predominantly from CT, which in the USA has recently doubled the average per person background dose to 4–6 mSv. For comparison, two radiographs of the chest give 0.02–0.08 mSv – less radiation than received on a round trip by air across the Pacific Ocean.

Table 7.1.1 Estimated equivalent background radiation for various imaging procedures

| Study | Estimated equivalent background assuming background of 2.5 mSv/year |

|---|---|

| Chest X-ray, 2 views | 3 days |

| Abdominal X-ray, 2 views | 1 week |

| Extremity X-ray, 2–3 views | 5 hours |

| Skull series X-ray, 3 views* | 3 weeks |

| Upper gastrointestinal series* | 6–12 months |

| Barium enema* | 8–16 months |

| MCU (VCUG) | 1–7 weeks |

| Chest CT | 12–18 months |

| Abdominal CT | 2 years |

| Cranial CT | 8–12 months |

CT, computed tomography; MCU, micturating cystourethrography; VCUG, voiding cystourethrography.

• Find out whether there are clinical guidelines for your department/institution. They may include guidelines for imaging.

• Generally, in a complicated case, it is best to begin with uncomplicated imaging, such as plain radiographs. They may provide the diagnosis; if not, they can help point the way to other studies.

• Provide relevant clinical information to the radiologist when requesting examinations.

• Consult a paediatric radiologist, or one experienced in paediatric diagnosis, when you have questions about the imaging of a specific clinical problem.

• Be prepared to answer questions from parents regarding ionizing radiation and know whom to ask for more information.

• Be familiar with the preparation, immediate complications and sequelae of invasive imaging procedures.

Neurology

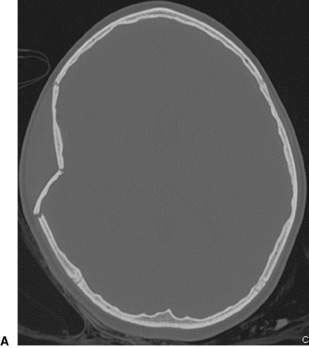

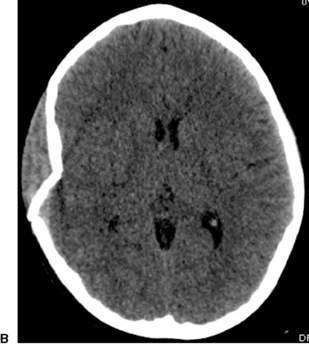

Acute head trauma, all ages

• CT of the brain following the CHALICE (Children’s Head injury ALgorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events) rule (Fig. 7.1.1).

• Use NEXUS clinical prediction rule (altered neurological function, intoxication, midline posterior spinal tenderness, and/or distracting injury) to identify which children and adolescents should have imaging of the cervical spine.

• MRI when CT findings are negative in an infant or child with persisting abnormal neurological signs.

Newborn

• Portable ultrasonography when screening for germinal matrix/intraventricular and intraparenchymal haemorrhage in the premature infant.

• CT for suspected acute extra-axial collections (bleeding, infection).

• MRI for suspected non-haemorrhagic parenchymal disease (e.g. hypoxic–ischaemic insult, neuronal migrational disorders).

Seizures

For acute non-febrile seizure:

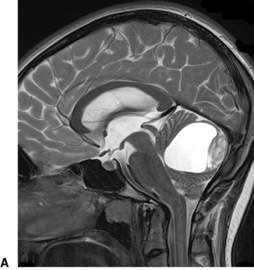

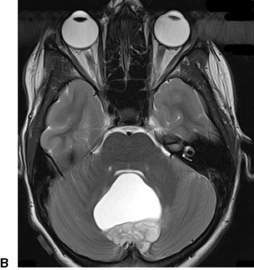

Altered conscious state, suspected tumour and stroke

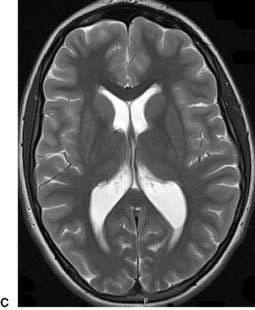

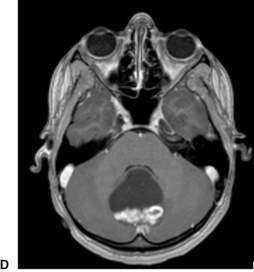

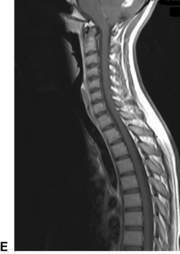

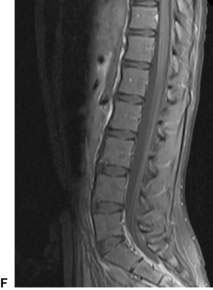

MRI is the preferred diagnostic test for a child presenting with acute neurological signs (Fig. 7.1.2). If MRI is not available, CT can diagnose established infarction, haemorrhage and most tumours. MRI is the preferred test as it detects infarction earlier, can provide perfusion imaging in the setting of stroke and angiographic sequences in the setting of vascular disease. It also provides more detailed imaging (in multiple planes) for surgical planning in the setting of tumour.

Cardiology

Suspected congenital heart disease

(E.g. abnormal prenatal ultrasonography, cyanosis, murmur, unexplained oxygen requirement.)

• Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiographs to include upper abdomen (Fig. 7.1.3)

• CT or MRI for anatomical detail of vascular rings as necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree