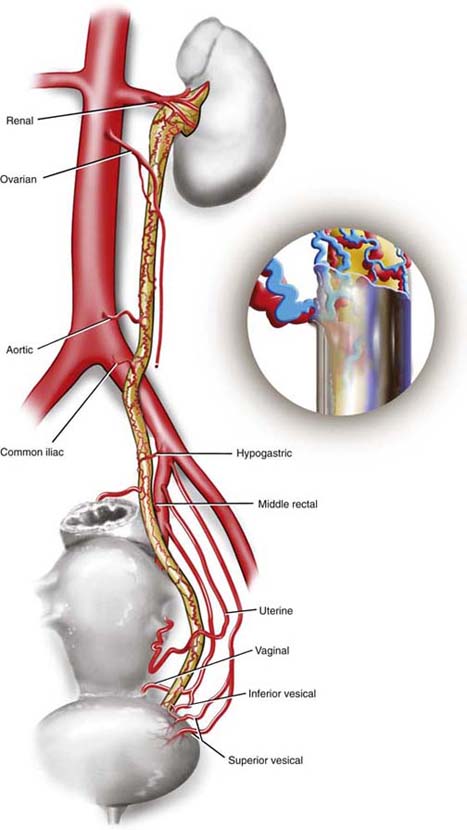

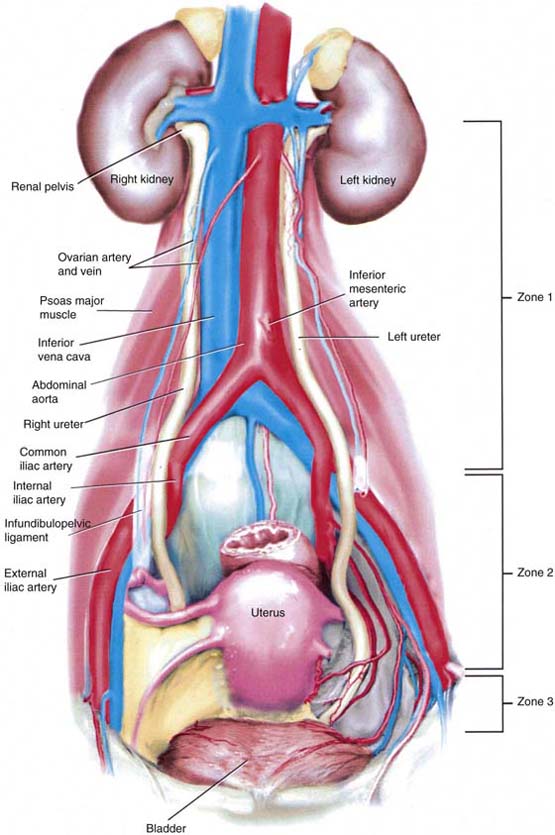

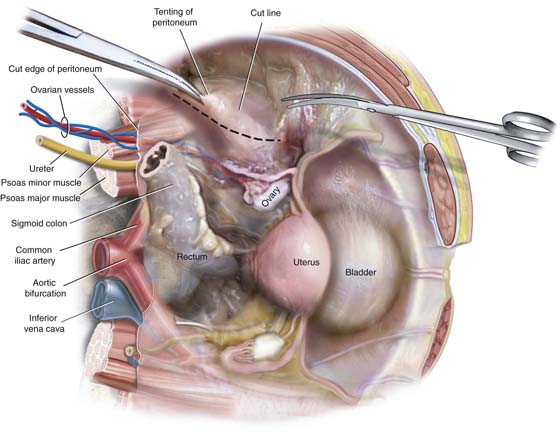

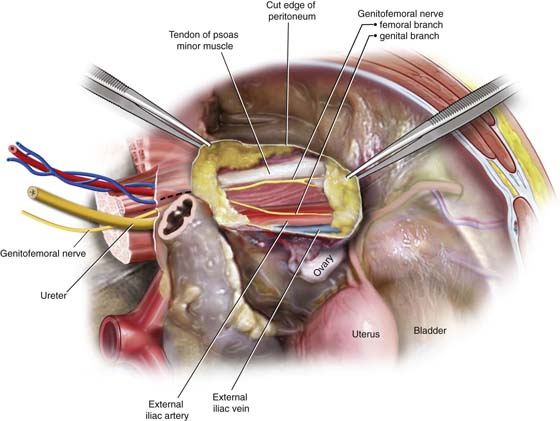

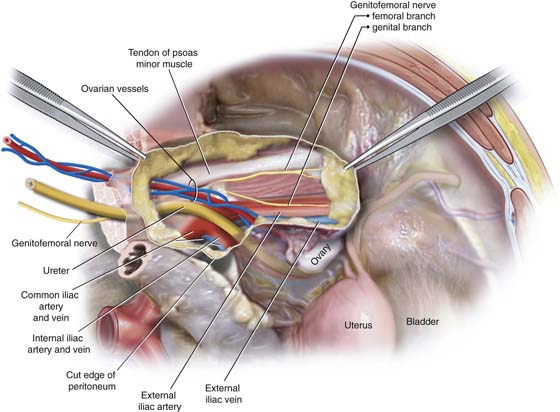

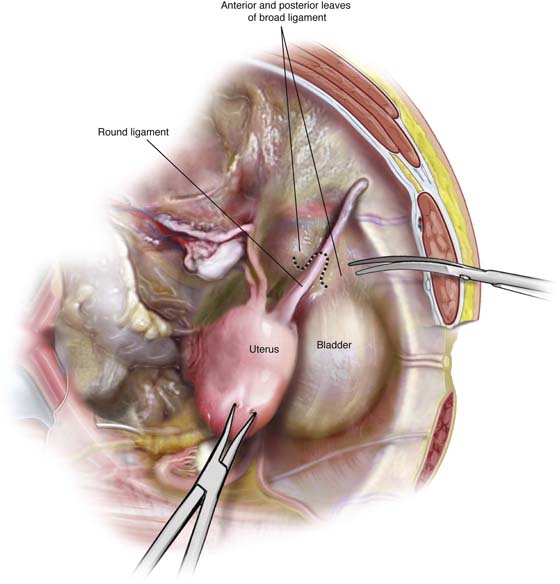

CHAPTER 37 The ureter is covered by an anastomotic network of small arteries and veins. Several larger vessels feed and drain this network. Generally, above the ureteral crossover of the common iliac vessels, the arterial blood supply emanates from the medial aspect (e.g., aortic, ovarian, renal). Within the pelvis, the arterial supply to the ureter enters from the lateral direction (e.g., hypogastric, uterine, vesical, vaginal) (Fig. 37–1). Although circulation is good, stripping the ureter of its adventitial sheath where its anastomotic network is located will result in segmental devitalization. Ureteral length ranges between 22 and 30 cm and extends from the renal pelvis to the ureteral orifice located at either extremity of the trigonal, ureteric ridge. The lumen of the muscular ureter is approximately 3.0 to 4.0 mm in diameter (9- to 12-French). The course of the ureter may be divided into three anatomic zones (Fig. 37–2). Zone 1: Between the renal pelvis and iliac arteries Zone 2: Between the ureteral crossover of the iliac arteries and the point where the uterine arteries cross over the ureter Zone 3: Between the uterine artery crossover of the ureter and the point where the ureters enter the urinary bladder The ureter is naturally narrowed at the ureteropelvic junction, at the iliac vessel crossover, and at the ureterovesical junction. The ureter is narrowed in its intramural passage through the bladder wall. During pregnancy, hypertrophied ovarian vessels may create obstruction of the ureter above the point where they cross it. The resulting hydroureter and hydronephrosis may cause pain and urinary infection. The right ureter is more frequently and more significantly obstructed than the left. Three techniques may be used to directly expose the pelvic ureter. These procedures require the surgeon to gain entry into the retroperitoneal space. The first and most direct entry point is reached by grasping the posterior parietal peritoneum overlying the psoas major muscle (lateral to the external iliac artery) and cutting the peritoneum in a parallel direction to the external iliac artery (Fig. 37–3). The latter artery is easily palpated at the medial edge of the psoas major muscle (Fig. 37–4). The external iliac artery is dissected cranially to the iliac bifurcation, where the ureter crosses into the pelvis superficial to the common iliac vessels and medial to the hypogastric vessels (Fig. 37–5). The ureter is smaller in diameter and is lighter (white) in color than the iliac artery. The ureter does not pulsate; however, it does demonstrate peristaltic activity. The second approach divides the round ligament so as to gain entry into the interior of the broad ligament (Fig. 37–6). The loose areolar tissue between the anterior and posterior leaves of the ligament is easily dissected with the tip of the Metzenbaum scissors or via a long tonsil clamp. As the dissection progresses deep to the floor of the broad ligament (i.e., passes the external iliac artery and vein), a white tubular structure comes into view, clinging to the medial leaf of the peritoneal edge. This is the ureter, which can be observed to undergo peristalsis (Fig. 37–7). The third approach requires the surgeon to grasp the right or left adnexa and gently create traction by stretching the infundibulopelvic ligament. This is accomplished by pulling the ovary and tube anteriorly and in a slightly caudal direction. The surgeon follows the infundibulopelvic ligament to the point where it enters the retroperitoneum (Fig. 37–8A). The peritoneum is picked up with a bayonet or other suitable toothed forceps and incised in a parallel direction to the ovarian vessels (Fig. 37–8B). The ureter lies posterior and medial to the ovarian vascular pedicle and in fact is attached to the ovarian vessels (one artery; two veins) at this location (Fig. 37–9). As in the other instances the ureter tends to be paler that the ovarian vessels and will be seen to undergo peristaltic activity. FIGURE 37–1 The ureter has its own vascular supply, which emanates from several neighboring vessels. These vessels include renal, ovarian, aortic, iliac, rectal, uterine, and vaginal. The network of anastomotic vessels supplies the ureter from the renal pelvis to the bladder and lies in the adventitia of the ureter. FIGURE 37–2 The three zones of ureteral anatomy. Although the shortest zone is zone 3, this is where most injuries occur. Note the anatomic differences between the right and left ureters. The left ureter is a bit more lateral in zones 1 and 2 and is lateral and to the left of the blood supply of the sigmoid colon (see Fig. 37–5). FIGURE 37–3 The parietal peritoneum overlying the psoas major muscle is grasped with forceps and opened by cutting with Metzenbaum scissors. The cut is linear and parallel to the course of the muscle. FIGURE 37–4 The tendon of the psoas minor muscle and the genitofemoral nerve is identified. At the medial margin of the psoas major muscle, the pulsations of the external iliac artery may be felt. The external iliac vein is immediately posterior and slightly medial to the artery. FIGURE 37–5 Following the external iliac artery cephalad will lead the surgeon to the ureter, where it courses superficial to the common iliac vessels. Note that the ovarian vessels are anterior and slightly lateral to the ureter. FIGURE 37–6

Identifying and Avoiding Ureteral Injury

Exposing the Ureter

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree