Chapter 36

Hypertensive Disorders

Brian T. Bateman MD, MSc, Linda S. Polley MD

Chapter Outline

Hypertension is the most common medical disorder of pregnancy, affecting 6% to 10% of pregnancies.1–4 It is a leading cause of maternal mortality, accounting for approximately 26% of maternal deaths in Latin America and the Caribbean, 9% of deaths in Africa and Asia, and 16% of deaths in the developed world.5 Hypertensive disorders are an important risk factor for fetal complications, including preterm birth, fetal growth restriction (also known as intrauterine growth restriction), and fetal/neonatal death.4,6–7

Classification of Hypertensive Disorders

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy encompass a range of conditions—chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension, and eclampsia—that can be difficult to diagnose because the clinical presentation is often similar despite complex differences in their underlying pathophysiologies and prognoses. Adding to the challenges for clinicians and researchers alike was a long-standing absence of consensus guidelines for categorizing hypertensive disorders. This lack resulted in the use of conflicting definitions that confounded attempts to compare and interpret data from many older clinical studies. This problem was resolved in 2000, when the National High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP) Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy3 published a classification scheme establishing definitions that subsequently gained wide international acceptance (Box 36-1). This classification was updated in 2013 when the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Taskforce on Hypertension in Pregnancy reviewed available literature and published a summary of current knowledge and recommendations.4

Gestational hypertension is the most frequent cause of hypertension during pregnancy, affecting approximately 5% of parturients.2,8,9 When mild, it results in outcomes that are generally similar to those of normotensive pregnancies,10,11 but when severe, it can result in rates of adverse pregnancy outcome that approximate those observed in preeclamptic women.12 Gestational hypertension presents as elevated blood pressure after 20 weeks’ gestation without proteinuria (in the absence of chronic hypertension) that resolves by 12 weeks postpartum.13,14 Most cases of gestational hypertension develop after 37 weeks’ gestation. Approximately one fourth of patients diagnosed with gestational hypertension will develop preeclampsia. A definitive diagnosis of gestational hypertension can be made only in retrospect after delivery when the diagnosis of chronic hypertension can be excluded based on a return to a normotensive state.

Preeclampsia is defined as the new onset of hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks’ gestation (Box 36-2). The NHBPEP recommends that clinicians also consider the diagnosis of preeclampsia in the absence of proteinuria when any of the following signs or symptoms of end-organ involvement are present: (1) persistent epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, (2) persistent cerebral symptoms, (3) fetal growth restriction, (4) thrombocytopenia, or (5) elevated serum liver enzymes.3 The term eclampsia is used when central nervous system (CNS) involvement results in the new onset of seizures in a woman with preeclampsia. HELLP syndrome refers to the development of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and a low platelet count in a woman with preeclampsia. This condition may be a variant of severe preeclampsia, but this classification is controversial because the disease may represent a pathophysiologically distinct entity.

Chronic hypertension involves either (1) prepregnancy systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher and/or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher or (2) elevated blood pressure that fails to resolve after delivery. Chronic hypertension develops into preeclampsia in approximately one fifth to one fourth of affected patients. However, even in the absence of preeclampsia, chronic hypertension is an important risk factor for adverse maternal and fetal pregnancy outcomes.6,15

Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia occurs when preeclampsia develops in a woman with chronic hypertension before pregnancy. The diagnosis is made in the presence of a new onset of proteinuria or a sudden increase in proteinuria or hypertension or both, or when other manifestations of severe preeclampsia appear. Morbidity is increased for both mother and fetus compared with preeclampsia alone.16

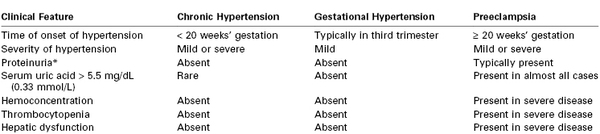

The clinical findings in chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia are compared in Table 36-1.

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is a multisystem disease unique to human pregnancy. It is characterized by diffuse endothelial dysfunction with maternal complications including placental abruption, pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, liver failure, stroke, and neonatal complications, including indicated preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, hypoxic-neurologic injury, and perinatal death.17 Although significant advances have been made in the understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease, the specific proximal cause remains unknown. Management is supportive; delivery of the infant and placenta remains the only definitive cure.

The clinical syndrome of preeclampsia is defined as the new onset of hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks’ gestation. Previous definitions included edema, but edema is no longer part of the diagnostic criteria because it lacks specificity and occurs in many healthy pregnant women. Preeclampsia is classified as preeclampsia without severe features or severe (see Box 36-2). The ACOG now discourages use of the term “mild” for preeclampsia without severe features because preeclampsia is progressive, and appropriate management involves frequent reevaluation for severe features.4

Some authors suggest classifying preeclampsia into the early form (type I), with symptom onset before 34 weeks’ gestation, or the late form (type II), with symptom onset after 34 weeks’ gestation (Table 36-2).18 Early-onset preeclampsia begins with abnormal placentation, has a high rate of recurrence, and has a strong genetic component.19–21 In contrast, late-onset preeclampsia generally occurs in women metabolically predisposed to the disease, and abnormal placentation may feature less prominently in the pathogenesis. These women, who often have long-standing hypertension, obesity, diabetes, or other forms of microvascular disease, are challenged to meet the demands of the growing fetoplacental unit and decompensate near term. Decompensation manifests as late-onset or, less frequently, postpartum preeclampsia.18

TABLE 36-2

Differences between Early- and Late-Onset Preeclampsia

| Early Onset | Late Onset | |

| Onset of clinical symptoms | < 34 weeks’ gestation | > 34 weeks’ gestation |

| Relative frequency | 20% of cases | 80% of cases |

| Risk for adverse outcome | High | Negligible |

| Association with fetal growth restriction | Yes | No |

| Clear familial component* | Yes | No |

| Placental morphology | Abnormal† | Normal† |

| Etiology | Primarily placental‡ | Primarily maternal§ |

| Risk factor (relative risk) | Family history (2.9) | Diabetes (3.56) Multiple pregnancy (2.93) Increased blood pressure at registration (1.38) Increased body mass index (2.47) Maternal age ≥ 40 years (1.96) Cardiovascular disorders (3.84) |

* Defined as recurrence across generations and occurrence within families.

† From Egbor M, Ansari T, Morris N, et al. Morphometric placental villous and vascular abnormalities in early- and late-onset preeclampsia with and without fetal growth restriction. BJOG 2006; 113:580-9.

‡ Reduced extravillous trophoblast invasion.

§ Predisposed maternal constitution reflecting microvascular disease or predisposed genetic constitution with cis– or trans-acting genomic variations subject to interaction.

From Oudejans CB, van Dijk M, Oosterkamp M, et al. Genetics of preeclampsia: paradigm shifts. Hum Genet 2007; 120:607-12.

Epidemiology

Preeclampsia occurs in 3% to 4% of pregnancies in the United States.2,9 Delivery of the infant and placenta is the only definitive treatment; thus, preeclampsia is a leading cause of indicated preterm delivery in developed countries.22 Low-birth-weight and preterm infants born to preeclamptic mothers present major medical, social, and economic burdens to families and societies.23 Preterm delivery is the most common indication for admission to the neonatal intensive care unit.24 Preeclampsia is also a leading indication for maternal peripartum admission to an intensive care unit.25,26

The clinical findings of preeclampsia can manifest as a maternal syndrome (e.g., hypertension and proteinuria with or without other systemic abnormalities) with or without an accompanying fetal syndrome (e.g., fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios, abnormal oxygen exchange).3,17 In approximately 75% of cases, preeclampsia occurs without severe features near term or during the intrapartum period.17 In contrast, disease onset prior to 34 weeks’ gestation correlates with increased disease severity and worse outcomes for both mother and fetus.

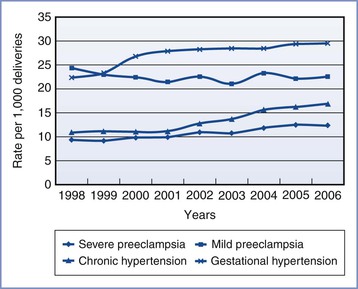

A significant increase in the incidence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy has occurred over the past decade (Figure 36-1), including an alarming 30% increase in severe preeclampsia/eclampsia.2 These increases are at least partially explained by major shifts in the demographics and clinical conditions of pregnant women in the United States and other developed countries. Average maternal age is increasing; advanced maternal age is a recognized risk factor for preeclampsia. Both the growing epidemic of obesity and the increased prevalence of diabetes and chronic hypertension in the developed world may also contribute to this trend. An increase in the use of assisted reproductive techniques and the use of donated gametes is contributory; these techniques increase risk for the disease by altering the maternal-fetal immune reaction27 and by increasing the incidence of multiple gestation. Last, improvements in record-keeping and the use of consistent disease definitions since 2000 may have contributed to the increased number of reported cases.3

FIGURE 36-1 Age-adjusted prevalence of hypertensive disorders during delivery hospitalization in the United States. (From Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113:1299-306.)

Numerous preconception and pregnancy-related risk factors associated with the development of preeclampsia have been identified (Box 36-3). Risk factors for preeclampsia can be divided into maternal demographic factors, genetic factors, medical conditions, obstetric conditions, behavioral factors, and partner-related factors.

Risk Factors

Demographic Factors.

Advanced maternal age has consistently been shown to be a risk factor for preeclampsia, with women who are 40 years or older having an approximately twofold increase in risk compared with women between 20 and 29 years of age.28,29 This risk may be independent of the increased prevalence of medical conditions and obesity that accompany advancing age.28 Teenage pregnancy may also be a risk factor for preeclampsia,30–32 but data are mixed.33

Black women constitute a high-risk group, with increased rates of chronic hypertension,34,35 obesity,35,36 and preeclampsia.37–40 Black women with severe preeclampsia demonstrate more extreme hypertension, require more antihypertensive therapy,41 and are more likely to die of the condition, compared with women of other racial backgrounds.42 Hispanic ethnicity may also confer increased risk for developing preeclampsia.43,44

Genetic Factors.

Maternal genetic factors are known to be important risk factors for the development of preeclampsia. Pregnant women with a family history of preeclampsia are approximately twice as likely to develop the disorder.45,46 It is estimated that about one third of the variance in liability to preeclampsia is caused by maternal genetic factors.47

In a study of 1.7 million births in the Medical Birth Registry of Norway, men who fathered one preeclamptic pregnancy were found to be nearly twice as likely to father a preeclamptic pregnancy in a different woman, irrespective of her previous obstetric history.48 Therefore, paternal genes (in the fetus) contribute significantly to a pregnant woman’s risk for preeclampsia. It is estimated that approximately one fifth of the variance in liability for preeclampsia is conferred through the fetal genes.47

Women with a history of preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy are at increased risk for preeclampsia in a subsequent pregnancy,29,49 particularly if the preeclampsia was of early-onset in the previous pregnancy.50 Risk for recurrence increases with multiple affected pregnancies.50 In addition, women with a history of previous placental abruption and fetal growth restriction are at increased risk for preeclampsia in a subsequent pregnancy,51 and women with a history of preeclampsia are at risk for these outcomes even in the absence of recurrent preeclampsia.52 These associations suggest that some women harbor a susceptibility (potentially genetically mediated) to obstetric conditions caused by placental dysfunction, which manifests differently in different pregnancies.

Medical and Obstetric Conditions.

Obesity is an important risk factor for preeclampsia, and risk escalates with increasing body mass index (BMI).53,54 A systematic review found that an increase in BMI of 5 to 7 kg/m2 was associated with a twofold increased risk for preeclampsia.53 Obesity is strongly associated with insulin resistance, another risk factor for preeclampsia. As the prevalence of obesity continues to increase worldwide, it is likely that the incidence of preeclamptic pregnancies will increase as well.

Women with chronic hypertension are also at increased risk for preeclampsia. A 2012 population-based study found that primary hypertension increased the odds of developing preeclampsia 10-fold and that secondary hypertension increased the odds nearly 12-fold.6 Chronic hypertension in association with other risk factors, including diabetes, renal disease, and collagen vascular disease, confers particularly elevated risk.6 As women in developed countries delay childbirth, the impact of chronic hypertension will increase because of the increased prevalence of hypertension with advancing age.55 Indeed, recent data from the United States show a substantial increase in the prevalence of chronic hypertension during pregnancy.2,6

Diabetes mellitus is associated with the development of preeclampsia.6,29 In a study of 334 diabetic pregnancies, the incidence of preeclampsia was 9.9%, compared with 4.3% in nondiabetic control pregnancies. The incidence of preeclampsia also increased with the severity of diabetes as determined by the White classification.56

The metabolic syndrome, which occurs in 7% of women of childbearing age in the United States, is characterized by the presence of obesity, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension.57 The metabolic syndrome increases risk for preeclampsia.58 The insulin resistance and microvascular dysfunction observed in this condition have been implicated as a common factor in both preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease; these conditions may partially mediate the association of preeclampsia and increased risk for cardiovascular disease later in life.59–61

Additional maternal medical conditions that are well recognized risk factors for preeclampsia include chronic renal disease,62,63 antiphospholipid antibody syndrome,29 and systemic lupus erythematosus.6,64 Pregnancy-related conditions that increase placental mass, including multifetal gestation29,65 and hydatidiform mole,66 are associated with higher rates of preeclampsia as well.

Behavioral Factors.

Paradoxically, cigarette smoking during pregnancy has been associated with a decreased risk for preeclampsia,67,68 an effect consistently observed across studies in various countries. Women who smoke during pregnancy have a 30% to 40% lower risk for developing preeclampsia compared with women who do not smoke. The protective effect is dose related67; heavier smokers have a lower incidence of preeclampsia than those who smoke fewer cigarettes.

The duration of this protective effect after smoking cessation has been studied with conflicting results. Its biologic mechanism remains unknown, but it is believed that the mechanism may include nicotine inhibition of thromboxane A2 synthesis,69 simulation of nitric oxide release,70 or a combination of these factors. Further research of this protective mechanism may help elucidate the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Recreational Physical Activity.

Recreational physical activity during pregnancy has been associated with a decrease in the risk for preeclampsia,71,72 particularly in nonobese women.73 Mechanistically, this may occur through exercise promoting placenta growth, decreasing oxidative stress, enhancing endothelial function, and modulating the immune and inflammatory response.72

Partner-Related Risk Factors.

The unifying theme among partner-related risk factors is limited maternal exposure to paternal sperm antigens before conception, which suggests an immunologic role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. A leading risk factor for preeclampsia is nulliparity; the incidence is approximately threefold higher compared with parous women.29 Long considered a disease of primigravid women, preeclampsia is also more common in (1) parous women who have conceived with a new partner, (2) women who have used barrier methods of contraception prior to conception, and (3) women who have conceived with donated sperm.74,75 Long-term sperm exposure with the same partner appears to be protective; this protective effect is lost in a pregnancy conceived with a new partner.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenic mechanisms responsible for the initiation and progression of preeclampsia are not known. The placenta is the focus of hypotheses regarding disease pathogenesis; delivery of the placenta results in the resolution of disease, and the disease can occur in the absence of a fetus (e.g., a molar pregnancy).76

Preeclampsia as a Two-Stage Disorder

Contemporary hypotheses generally conceptualize preeclampsia as a two-stage disorder.77 The asymptomatic first stage occurs early in pregnancy with impaired remodeling of the spiral arteries (the end branches of the uterine artery that supply the placenta).76 In normal pregnancy, embryo-derived cytotrophoblasts invade the decidual and myometrial segments of the spiral arteries, replacing endothelium and causing remodeling of vascular smooth muscle and the inner elastic lamina (Figure 36-2).78,79

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree