Hydrocephalus and Pseudotumor Cerebri

Nicole J. Ullrich

HYDROCEPHALUS

Hydrocephalus is a condition in which there is an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the ventricles, leading to increased intracranial pressure. Hydrocephalus may be caused by increased production, decreased absorption, or obstruction to flow of CSF. By contrast, ventricular dilatation due to loss of brain tissue or atrophy is not considered to be hydrocephalus.

CEREBROSPINAL FLUID DYNAMICS

CEREBROSPINAL FLUID DYNAMICS

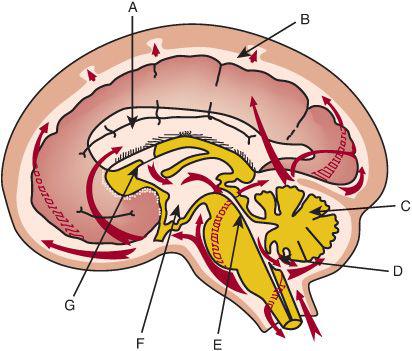

Typically, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is produced at a volume of 20 mL/hour, or more than 500 mL per day, in the adult. Total CSF volume in infants is approximately 50 mL, as compared to approximately 150 mL in normal adults. Cerebrospinal fluid is produced by active secretion and diffusion predominantly in the choroid plexus, located in the lateral ventricles and the roof of the fourth ventricle. Cerebrospinal fluid passes from the lateral ventricles into the paired foramina of Monro to reach the third ventricle and then along the cerebral aqueduct into the fourth ventricle. Once in the fourth ventricle, CSF flows through the midline foramen of Magendie or laterally through the paired foramina of Luschka into focally enlarged areas of subarachnoid space known as the basal cisterns, which connect the spinal and intracranial subarachnoid spaces (Fig. 553-1). Cerebrospinal fluid is in continual flow around the brain and spinal cord and within the ventricles in a cephalad direction. Production of CSF is regulated by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, and reabsorption occurs within the arachnoid villi in the meninges into the venous channels of the sagittal sinus. Smaller amounts of CSF absorption also occurs across the ependymal lining of the ventricles. Typically, there is a delicate balance between CSF production and reabsorption; hydrocephalus results when that balance is disrupted. However, CSF production rarely fluctuates in normal circumstances and even in the face of rising intracranial pressure, unless extremely elevated pressures are reached.

POTENTIAL ETIOLOGIES

POTENTIAL ETIOLOGIES

Hydrocephalus is generally classified as communicating, obstructive, and external, depending on the underlying etiology.1 Communicating hydrocephalus refers to a situation in which cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flows freely into the subarachnoid space, but the total volume of CSF is increased secondary to either impaired reabsorption or overproduction. Impaired reuptake of CSF may result from blood within the ventricular system (as occurs with subarachnoid hemorrhage) increased protein content (resulting from meningitis) or an increased cell content from malignant cells such as leukemia. Some tumors, such as choroid plexus tumors, may increase CSF production thereby contributing to hydrocephalus (Fig. 553-2).2

Obstructive, or noncommunicating hydrocephalus, results from obstruction to the outflow of CSF. Aqueductal stenosis is the most frequent cause, accounting for about 20% of cases, with an incidence of 0.5 to 1 per 1000 births.3 Anatomically, the cerebral aqueduct is vulnerable to external compression because of its long, narrow tract connecting the third and fourth ventricles. Stenosis may be congenital, often associated with spina bifida, or may result from inflammatory or neoplastic processes. The Chiari malformation describes a condition in which the inferior poles of the cerebellum protrude caudally into the foramen magnum, resulting in compression of the medulla (Fig. 553-3). These malformations, either alone or in combination with other congenital abnormalities, account for 40% of cases of hydrocephalus.4,5

Any decrease in cerebral venous drainage (and resultant increase in cerebral venous pressure), as seen with cerebral or jugular vein thromboses, can result in increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and hydrocephalus. In addition, superior mediastinal obstruction compromising superior vena cava flow has been reported as a cause of increased ICP.6,7

FIGURE 553-1. Schematic diagram of a sagittal section of the brain with arrows that trace the flow of cerebrospinal fluid. Cerebrospinal fluid flows out of the ventricular system through the fourth ventricle outlets into the basal cisterns, and then through the tentorium over the cerebral hemispheres toward the arachnoid granulations in the superior sagittal sinus. There is bidirectional flow of CSF in the spinal canal. A, lateral ventricle; B, subarachnoid space; C, cerebellum; D, foramen of Magendie; E, aqueduct of Sylvius; F, third ventricle; G, foramen of Monro.

Benign enlargement of the subarachnoid space, otherwise referred to as benign extra-axial fluid, external hydrocephalus, idiopathic external hydrocephalus, or extraventricular hydrocephalus, is relatively common, occurring in approximately 16% of infants.8,9 Head circumference typically increases to greater than the 90th percentile and then parallels the normal curve. The head growth velocity then slows to normal by the age of 6 months. Typically these children experience normal development and have normal neurologic examination; nonetheless, their development should be monitored closely.10 This benign increase in the size of the subarachnoid space should be contrasted with the extra-axial fluid collections that are observed in children who spent extensive periods of time in the neonatal intensive care unit or on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. In these circumstances, the increased head size and fluid collections may be associated with adverse neurologic sequelae and/or poor developmental outcomes.11

CLINICAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

CLINICAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The clinical signs and symptoms of hydrocephalus are nonspecific and independent of underlying etiology. In young children, the most obvious sign of hydrocephalus is a rapid increase in head size, often accompanied by a bulging, enlarged anterior fontanel, conspicuous scalp veins, and/or frontal bossing.3 Other symptoms may include irritability, increased sleepiness, vomiting, seizures, and downward eye deviation—the “setting sun sign”—in which the sclerae are visible above the iris.12 In older children, symptoms of hydrocephalus reflect the increased intracranial pressure and include headaches, nausea, vomiting, and, occasionally, changes in vision with double vision and/or blurry vision. Headaches that are the result of increased intracranial pressure often occur early in the morning and may be associated with nausea and vomiting. Prolonged increases in intracranial pressure (ICP) may be accompanied by changes on ophthalmological examination, such as papilledema, as well as changes in balance or walking and increased sleepiness. Physical examination may also demonstrate palsies of the third or sixth cranial nerves.

EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF HYDROCEPHALUS: CEREBROSPINAL FLUID DIVERSION

EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF HYDROCEPHALUS: CEREBROSPINAL FLUID DIVERSION

Evaluation for hydrocephalus includes imaging studies to assess the ventricular size and to assess for signs of anatomical obstruction, the presence of mass lesions, or signs of impending herniation. In young infants, ultrasonography is the preferred imaging modality, because it is portable and avoids ionizing radiation. In older children, computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed.13 In addition, direct ophthalmoscopy is useful to evaluate for signs of papilledema, reflecting increased intracranial pressure (Fig. 553-4).12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree