Introduction

Medical management for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) infected pregnant women encompasses both prevention of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV-1 and contemporary standards for evaluation and treatment of HIV-infected adults. This chapter will present an overview of HIV disease including its diagnosis and treatment in adults, discuss counseling for HIV-infected women of reproductive age, and outline specifics of the obstetric, medical, anesthetic, and postpartum management of HIV-infected pregnant women.

Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus infection in women

Over half of the 39.5 million people living with HIV in 2006 were women. In sub-Saharan Africa, 60% of the 25 million HIV-infected adults are women. The number of HIV-infected females continues to rise, with the greatest increases in Eastern Europe, Asia, and Latin America. In North America an estimated 350,000 women are living with HIV, an increase of 50,000 from 2004 to 2006 [1]. The primary mode of transmission among women is heterosexual transmission.

In the United States, HIV disproportionately affects women of color. In 2004, HIV was the leading cause of death among African American women aged 25–34 and the third and fourth leading cause among ages 35–44 and 45–54 years respectively. The incidence of AIDS for African American women (49.9/100,000) is 24 times and four times higher than for white women (2.1/100,000) and Hispanic women (12.2/100,000), respectively [2]. Lack of perception of risk and relationship dynamics, including inability to negotiate condom use and fear of violence, contribute to growing rates of HIV infection among young women.

Screening for human immunodeficiency virus infection in pregnancy

Human immunodeficiency virus testing of all pregnant women is recommended [3]. Recommendations are for testing to be performed unless declined (“opt out”), without separate written informed consent unless required by specific law. Testing should be done early in pregnancy, and repeated in the third trimester if early testing was not done or was initially negative in “at-risk” women. Risk factors include high-prevalence geographic areas or healthcare facilities, and personal factors, including injection drug use, exchanging sex for money or drugs, sex partners of HIV-infected persons or drug users, and a new or more than one sex partner during this pregnancy. Rapid HIV testing at the time of labor is recommended if HIV infection status has not previously been documented during the index pregnancy.

Diagnostic tests for human immunodeficiency virus infection

The diagnosis of HIV infection is made by detecting either antibodies to HIV or HIV viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) in blood by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing (HIV RNA-PCR). The standard antibody assay is the enzyme-linked immunoassay (EIA, also known as ELISA) performed on serum. In addition, there are several different rapid EIA tests that utilize blood, and the Oraquick test can be performed on oral fluid samples. An initial positive EIA test must be confirmed with a second, more specific test: a Western blot, immunoflorescence assay or HIV RNA-PCR [3,4]. The Western blot detects antibodies to specific HIV antigens; positivity requires the presence of antibodies to two of the following: p 24, gp 41, and gp 120/160. Testing is indeterminate if the EIA is positive and the Western blot shows antibody to only a single HIV antigen. Negative confirmatory testing should be repeated in the third trimester in “at-risk” women, and indeterminate testing should prompt both repeat testing and referral to a specialist.

Causes of indeterminate results include partial seroconversion, advanced acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) with decreased antibody titers, blood transfusions, organ transplantation, autoimmune disease and experimental HIV vaccines. Risk factors must be assessed when evaluating an indeterminate test. HIV infection is unlikely in low-risk patients with repeat indeterminate testing in 3 months. Patients in the process of seroconversion will usually have a positive Western blot within 1 month.

Gestational age must be considered in making decisions about treatment in the case of indeterminate testing [5]. Waiting 1 and 3 months to repeat testing is reasonable in early pregnancy. Viral testing can be used and if negative, treatment can be deferred pending follow-up antibody testing. Close to delivery, indeterminate tests should prompt antiretroviral treatment, as should any positive antibody testing at the time of labor and delivery.

Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection

Principles of therapy are based on the pathogenesis of HIV infection. The clinical features and pathogenesis of primary infection have been recently reviewed [6,7]. Primary HIV infection is followed by a dramatic increase in plasma viremia, sometimes accompanied by a distinct clinical syndrome consisting of fever, adenopathy, malaise, myalgia, pharyngitis, rash and in some cases aseptic meningitis. Cells with CD4+ receptors become infected and viral replication begins within them. Infected cells release virions by surface budding or lysis, leading to infection of additional cells. HIV-directed sequences become incorporated into host DNA during replication and remain so until cell death. A reservoir of long-lived, infected resting T-cells is established early on and persists for many years, even in the presence of treatment. This reservoir can harbor drug-resistant virus when patients are exposed to suboptimal treatment regimens.

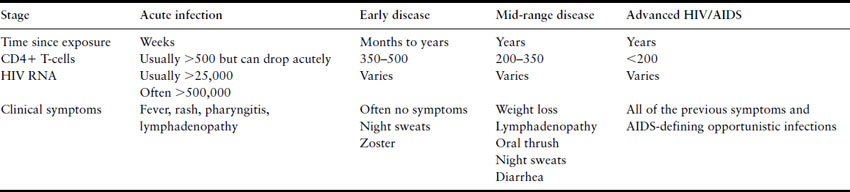

The number of CD4+ T-lymphocytes declines acutely, stabilizes, and then rebounds as the immune system, CD8+ T-lymphocytes in particular, works to control viral replication. After a new equilibrium is reached in which the rate of production of new CD4+ T-cells equals the rate of destruction, a person may remain asymptomatic for a number of years. Viral replication continues, and over time the plasma viral load increases and the number of CD4 + T-lymphocytes declines. Monitoring the CD4+ cell count helps to establish the stage of HIV disease. Mild symptoms such as weight loss, lymphadenopathy, and a variety of skin problems (mucocutaneous ulcers and/or rash with the initial seroconversion and oral hairy leukoplakia, thrush, persistent vaginal candidiasis with early symptomatic disease) often occur early in the course of symptomatic HIV disease. Most AIDS-related opportunistic infections do not occur until the CD4+ cell count falls below 200 cells/mm3. This typically develops 10 or more years after infection [8]. The risk of disease progression increases with time and is thought to ultimately be very high without treatment.

Although mild symptoms can occur early in the course of HIV disease, patients can remain completely asymptomatic for a long period of time. The absence of symptoms should not preclude HIV testing.

Human immunodeficiency virus mutates readily and several viral variants emerge over time in an individual, some of which are capable of immune control. Chronic immune system activation is thought to contribute to CD4+ cell loss and reduced efficacy of B-cell responses to bacterial pathogens.

More severe symptoms and development of AIDS-defining illnesses occur when a significant number of CD4+ T-lymphocytes has been destroyed and production cannot match destruction (Table 18.1). PCP pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci remains the most common initial opportunistic infection (OI), although with PCP prophylaxis the incidence has decreased. Other OI occurring early in the course of AIDS include cryptococcal meningitis, cerebral toxoplasmosis, recurrent bacterial infections, including bacteremia and pneumococcal pneumonia, and severe herpes simplex infection. Later complications include disseminated cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection.

Table 18.1 Time course of HIV infection without treatment

Several cohort studies have contributed to understanding the natural history and outcomes of women with HIV infection [9–11]. Kaposi’s sarcoma is more common in men, and esophageal candidiasis and bacterial infections may be more common in women, but otherwise HIV-related complications are similar in men and women [12,13]. There is no indication that women have a different course once OI have occurred or that they respond differently to commonly used therapies. Women have lower HIV-1 RNA levels than do men, especially early in disease [14]. Early studies suggested that HIV-infected women had a more rapid rate of disease progression and shortened survival after diagnosis compared to men [15]. Other studies have not found gender differences in survival or attribute survival differences to stage of disease when diagnosed, or differential utilization of healthcare resources including antiretroviral therapy (ART) [16,17].

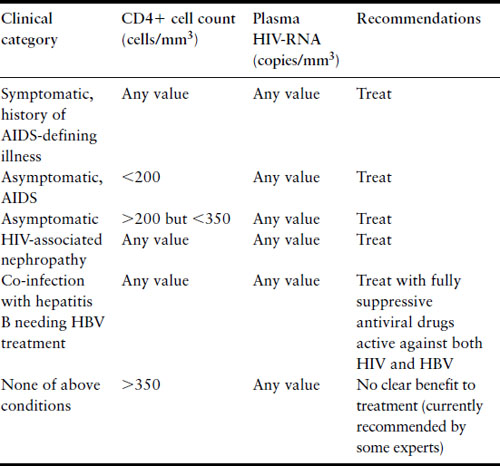

Table 18.2 Current recommendations for initiation of antiretroviral therapy for nonpregnant patients [20]

Antiretroviral therapy prolongs life and extends disease-free survival in HIV infection [18,19]. Efficacy is judged by clinical criteria, improvement in CD4+ cell count, and suppression or decrease in viral load. Current recommendations for ART initiation balance efficacy, long-term ART toxicity and development of drug resistance (Table 18.2). Combinations of at least three separate highly active antiretroviral agents (HAART) are associated with the greatest efficacy and least development of resistance. The major classes of agents include nucleoside and nucleotide analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI), and protease inhibitors (PI), although drugs with other modes of actions have entered into the armamentarium. Combination regimens for initial ART typically consist of two separate NRTI and either an NNRTI or a PI. US Public Health Service guidelines for treatment of HIV-infected adults are published, posted online, and continually updated [20].

With the advent of HAART, HIV-infected women are living longer and healthier lives. Attitudes towards having children are more positive. All HIV-infected women of reproductive age should receive preconception counseling, starting early during HIV care. Preconception counseling should include information about MTCT, the importance of maximizing health and minimizing viral load surrounding pregnancy, utilization of ART, and potential short- and long-term implications of HIV treatments during pregnancy for women and their infants.

Preconception counseling also offers the opportunity to advise on safe sex practices and discuss methods to prevent unintended pregnancies. HIV testing of sex partners should be encouraged. For discordant couples, options such as intravaginal or intrauterine insemination and other assisted reproductive technologies to achieve pregnancy should be discussed. Counseling and referrals for cessation of smoking and illicit drug use are also appropriate.

A substantial number of women are identified as HIV infected during prenatal testing. These women need to receive the same information about MTCT, ART, their own health, and long-term follow-up as provided during preconception counseling.

Without ART, the MTCT rate centers around 25%. Transmission occurs antepartum, intrapartum, and postnatally through breastfeeding. Two-thirds to three-quarters occurs during or close to the intrapartum period [21]. In resource-limited settings, breastfeeding accounts for approximately 40% of peripartum/postnatal HIV transmission [22].

Maternal factors associated with MTCT include advanced HIV disease, high plasma viral load, low CD4+ cell count, poor maternal nutrition, and maternal illicit drug use, smoking, and sexually transmitted diseases [23–26]. Obstetric factors include prolonged rupture of membranes, chorio-amnionitis, and route of delivery [25,27,28]. Fetal factors include low birthweight, prematurity, and genetic susceptibility [25,29]. Viral phenotype and genotype may also affect transmission rates [30]. The two most important factors affecting MTCT are maternal viral load and ART use during pregnancy.

Viral load near term correlates with risk of MTCT among both untreated women and women treated with ART during pregnancy. Women with HIV RNA levels <1000 copies have very low rates of MTCT [24,26]. However, HIV transmission has been documented even with low or undetectable maternal viral levels [31]. Although plasma and genital tract HIV levels correlate well, discordance between these two compartments [32,33] may explain some cases of MTCT despite low peripheral blood virus concentrations.

Since 1994, recommendations for ART for HIV-infected pregnant women have evolved in parallel with evolving standards for other adults. Combinations of three or more antiretroviral (ARV) agents maximally decrease MTCT compared with no ARV or zidovudine (ZDV, AZT) alone, and viral load and ART independently affect MTCT risk [34]. Current guidelines recommend antepartum, intrapartum, and postnatal infant ARV for fetal and neonatal protection regardless of viral load [35]. Finally, breastfeeding is not recommended in resource-rich countries to prevent postnatal HIV transmission.

Women should be told of the most common side effects of ARV, and informed of safety concerns, described in detail later in this chapter. They should be informed of the need for short- and long-term monitoring of both women and infants for potential effects of exposure to ARV during pregnancy.

Pregnancy does not accelerate immunologic decline or affect disease progression and survival among HIV-infected women [36,37]. There are reports of postpartum increases in HIV-1 RNA regardless of continuation of ART after delivery [38,39]. Decreased adherence or changes in ART postpartum may explain some of this increase.

Basic care for HIV infected pregnant women consists of:

- evaluation and therapy for maternal HIV disease

- ART for fetal protection and as appropriate for maternal health

- monitoring for ART toxicities

- PERIPARTUM management, including selection of route of delivery

- neonatal ART

- arrangements for long-term healthcare for both mother and infant.

Comprehensive care entails a team approach with co-ordinated efforts by multiple service providers (Box 18.1). Community-based obstetric care should be supplemented by consultation with specialists in maternal-fetal medicine or infectious diseases; alternatively care may be transferred to referral centers with expertise in HIV/AIDS. Management issues include:

- HIV education and counseling

- HIV testing of sexual partners and family members

- psychologic assessment and ongoing counseling

- drug abuse management

- supportive services

- adherence strategies for healthcare visits and ART.

Box 18.1 Referrals for HIV-infected pregnant women

- Maternal-fetal medicine specialist with expertise in perinatal HIV

- HIV specialist (internist or ID physician)

- Case manager/care co-ordinator

- Psychiatric/social services

- Drug treatment program

- Pediatrics

If a woman is receiving HIV care prior to pregnancy, results of recent laboratory evaluations and the currently prescribed ART should be confirmed. If a woman has not been receiving medical care or was recently diagnosed, the obstetric provider must initiate evaluations for HIV disease staging, and frequently co-existing conditions including OI, sexually transmitted diseases, illicit drug use, alcohol use, and both smoking and respiratory tract complications. Initial laboratory assessment of HIV-infected pregnant women is outlined in Box 18.2.

Antiretrovirals: choice of agents and initiation of therapy

Comprehensive guidelines for the use of ARV during pregnancy have been published and are posted online and continually updated [35]. All women should receive combination regimens of at least three ARV agents during pregnancy for fetal protection, regardless of the necessity of ART for maternal health. The exact ARV regimen should be individualized based on stage of maternal HIV disease, prior history of ART, and genotypic resistance to ARV. Regimens recommended for women who have not previously received ART are those recommended as initial therapy for HIV-infected adults. If possible, zidovudine should be included.

If a woman is on stable ART that has achieved good virologic control and immunologic effect, this should not be stopped during pregnancy. Discontinuation of ART can lead to viral rebound with the possibility of in utero fetal infection and emergence of resistant virus. No major teratogenic effects of commonly used ARV agents have been demonstrated [40]. The exception to this is the drug efavirenz (Sustiva), classified by the FDA as category D. Efavirenz is associated with neural tube defects in primates and four reported cases of significant CNS defects in infants exposed in utero to efavirenz during the first trimester, including three neural tube defects and one Dandy–Walker syndrome [41]. Other agents should be substituted for efavirenz during preconception counseling or as early as possible once pregnancy has been documented.

Box 18.2 Initial laboratory assessment of HIV-infected pregnant women

Staging/antiretroviral management

- CD4 + cell count

- Viral load (HIV RNA-PCR)

- HIV genotype

Co-existing conditions

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (if positive, hepatitis B DNA-PCR)

- Hepatitis C antibody (if positive, hepatitis C RNA-PCR)

- Serologic test for syphilis

- Toxoplasmosis IgG

- Cytomegalovirus IgG

- Gonorrhea, Chlamydia lower genital tract assessments

- Pap smear

Baseline laboratory tests for ARV toxicity monitoring

- CBC – platelet count

- Liver function tests

- BUN, creatinine

- Electrolytes

- Amylase

- G6PD

The timing of initiation of ART during pregnancy is determined by indication for use. If maternal viral load is low, immunologic suppression minimal, and the indication is fetal protection, ARV can be started after the first trimester. If indicated for maternal health, ART should be started as soon as possible.

Effectiveness and safety of ART are influenced by adherence to drug regimens as prescribed [42,43]. Inconsistent use with time periods of subtherapeutic drug levels promotes the development of genotypic resistance and virologic failure. In the case of hyperemesis gravidarum, all ARV should be stopped, or not instituted, until the medications can be taken as prescribed. If initiation of ART is associated with nausea and vomiting, antiemetics should be utilized. A variety of strategies to otherwise promote adherence have been suggested, including financial assistance, drug abuse services, and management of psychiatric issues. Hospitalization for directly observed therapy (DOT) and treatment of side effects may also be an effective strategy to maximize adherence.

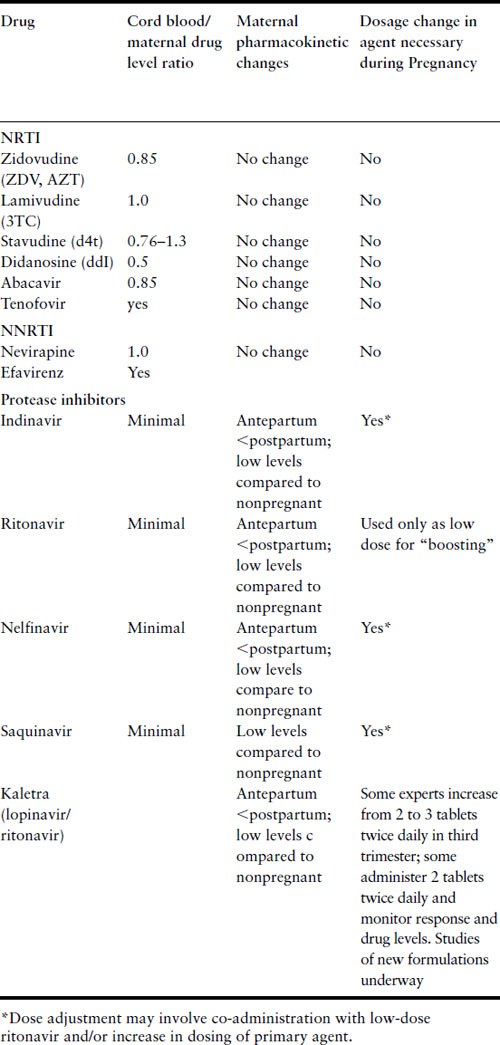

The pharmacokinetics during pregnancy of many of the ARV agents currently in use have been elucidated [35]. A summary of results of pharmacokinetics studies is presented in Table 18.3. In general, the pharmacokinetics of NRTI and NNRTI agents are not affected by pregnancy, and dose alterations are not necessary. There are substantial differences during pregnancy in the pharmacokinetic profiles of the PI that have been studied, with lower drug levels observed, often requiring dose modifications. Negligible levels of PI in cord blood have also been noted. The PI are metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 system; pharmacokinetic changes are likely due to alterations in hepatic metabolism during pregnancy as well as placental protein synthesis and drug metabolism.

Table 18.3 Pharmacokinetic properties of antiretroviral agents during pregnancy

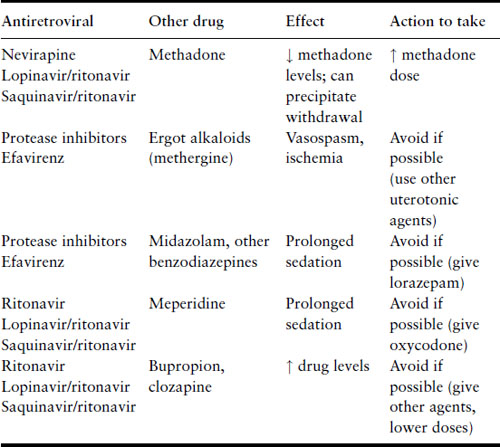

Some of the PI and the NNRTI efavirenz can induce or inhibit the hepatic metabolism of other medications, thereby altering drug levels or enhancing toxicities (Table 18.4). Of particular note, the concomitant use of ergotamines and PI or efavirenz has been associated with exaggerated vasoconstrictive responses. If a woman on PI develops uterine atony and bleeding, methergine should be used only if absolutely necessary.

Table 18.4 Drug–drug interactions, antiretrovirals and commonly used drugs

HIV viral load and CD4+ cell counts are checked within 2–4 weeks after initiating or changing ART. Once an effective regimen has been established, CD4+ cell counts are checked every 3 months and HIV viral loads are checked every 2 months and between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation in order to assist in determination of mode of delivery. The goal is to achieve a nondetectable viral load prior to delivery.

Laboratory monitoring for common hematologic, renal, hepatic, and metabolic side effects of ARV should occur periodically antepartum (see Table 18.5) and whenever suggestive signs or symptoms occur. Many experts recommend third-trimester monitoring for fetal growth and well-being, if women are receiving an ARV that has not been commonly used during pregnancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree