General Considerations

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that primarily infects cells of the immune system, including helper T lymphocytes (CD4 T lymphocytes), monocytes, and macrophages. The function and number of CD4 T lymphocytes and other affected cells are diminished by HIV infection, resulting in profound effects on both humoral and cell-mediated immunity. In the absence of treatment, HIV infection causes generalized immune incompetence, leading to conditions that meet the definition of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and, eventually, death. The clinical diagnosis of AIDS is made when an HIV-infected child develops any of the opportunistic infections, malignancies, or conditions listed in category C (Table 41–1). In adults and adolescents, the criteria for a diagnosis of AIDS also include an absolute CD4 T-lymphocyte count of 200 cells/μL or less.

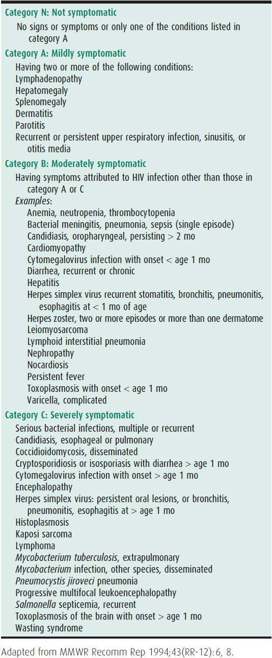

Table 41–1. Centers for disease control and prevention clinical categories of children with human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) can forestall disease progression for many years (≥ 20 years) if taken consistently. However, current treatment fails to eradicate the virus and treatment must be lifelong. The full duration of the favorable outcome of therapy is not yet defined, and it is not known whether adverse effects due to medications and incomplete immune restoration will limit use or impact mortality. Nevertheless, HIV infection can be considered a chronic disease for people with access to treatment rather than an acutely terminal disease.

Early diagnosis offers the opportunity to optimize treatment outcomes for children, adolescents, and adults. Treatment reduces the risk of transmission to others and thus has a public health benefit as well. In an effort to improve early diagnosis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that HIV screening tests be conducted in routine health care settings with patient knowledge and right to refuse for patients aged 13–64 years and that all adults should be tested at least once for HIV during their lives. In 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended at least one-time testing for 16- to 18-year-old adolescents, irrespective of risk factors, living in areas of high (≥ 0.1%) or unknown seroprevalence. In areas of lower seroprevalence, testing is encouraged for all sexually active adolescents and those with other risk factors for HIV infection.

American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement: Adolescents and HIV infection: the pediatrician’s role in promoting routine testing. Pediatrics 2011;128:1023–1029 [PMID: 22042816].

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated in 2012 that there were 32 million adults and 3.3 million children living with HIV (http://www.who.int/hiv/data/2012_epi_core_en.png). Over 90% live in low- and middle-income countries, primarily sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia. Although the number of new infections is estimated to have peaked globally in 1997, infection and mortality rates remain high. Among children younger than 15 years, there were 260,000 new infections and 210,000 deaths in 2012. High rates of new pediatric infections are the result of ongoing mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) in resource-limited settings where access to preventative measures is often not accessible; fewer than 60% of pregnant women received recommend treatment in 2011.

MTCT rates are 20%–40%, overall, if there is no intervention. Transmission occurs in utero, at the time of labor and delivery (peripartum), or during breast-feeding (postnatal transmission). However, MTCT can be reduced to less than 1%–2% with prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal interventions (see Prevention section). The successful implementation of these interventions in the United States has made new vertically acquired HIV cases rare (< 200 cases annually). In the United States, the number of children younger than 13 years living with HIV was estimated at 2936 in 2011. As a result of effective antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, perinatally infected children who receive treatment are surviving into adolescence and young adulthood. In the United States, perinatally infected individuals comprised 22% of those living with HIV in the 13- to 24-year-old age group.

After puberty, infections result primarily from sexual contact (men having sex with men [MSM] and heterosexual), with a smaller proportion resulting from injecting drug use. In 2011, there were approximately 50,000 new infections in the United States among which youth are overrepresented, since the proportion of new infections among young people aged 13–29 years exceeds this age group’s proportion in the total population (39% of new HIV infections vs 21% in the total population). Young adults, age 20–24 years, had the highest rates of new HIV infections (36.9/100,000 people) in 2009. Most at risk are young black MSM, in whom new infections increased 48% between 2006 and 2009.

Occupational exposure resulting from accidental needle sticks or, rarely, mucosal exposure to blood may occur. As a result of careful donor screening and testing of donated blood, HIV transmission resulting from blood products is now extremely rare in the United States (1:2,000,000 transfusions). Casual, classroom, or household contact with an HIV-infected person poses no risk of transmission.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HIV/AIDS, Statistics and Surveillance, Statistics Center: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/index.htm. Accessed January 25, 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV/AIDS Statistics and Surveillance, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD & TB prevention, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Epidemiology of HIV infection (through 2011) slide set: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/general/slides/Epi-HIV-infection.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HIV/AIDS, Topics, HIV among youth: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/youth/index.htm. Accessed April 19, 2013.

World Health Organization (WHO) HIV/AIDS Data and Statistics, Global epidemic and health care response (PowerPoint slides): http://www.who.int/hiv/data/en/. Accessed January 25, 2014.

Mode of Transmission and Pathogenesis

Mode of Transmission and Pathogenesis

In most cases, HIV infection occurs via mucosal exposure. Information on the early events of HIV infection is based on nonhuman primate models and studies in adults infected by sexual transmission; the events in MTCT are less well studied. At the time of exposure, virus breaches the mucosal barrier, is transported to regional lymph nodes, replicates, and spreads throughout all lymphoid tissues. Based on nonhuman primate models, replicating virus is found throughout the lymphoid tissue by 48 hours postinfection. During the first days after infection, there is a massive loss of mature CD4 T-helper lymphocytes, especially in the gut mucosa. Approximately 2 weeks after exposure, high levels of HIV are detected in the bloodstream. In adults, the level of viremia declines, without therapy, concurrent with the appearance of an HIV-specific host immune response, and plasma viremia usually reaches a steady-state level about 6 months after primary infection. The amount of virus present in the plasma at that point, known as the “set point,” and thereafter is predictive of the rate of disease progression for the individual. A period of clinical latency usually occurs, lasting from 1 year to more than 12 years, during which the infected person is asymptomatic. However, ongoing viremia and immune activation causes subclinical injury to the immune and other organ systems. The virus and anti-HIV immune responses are in a steady state such that CD4 T-lymphocyte parameters may be stable. Eventually, the balance favors the virus, and the viral burden increases as the CD4 T-lymphocyte count declines, at which time the individual becomes susceptible to opportunistic infections.

Infants with in utero HIV infection have virus detectable in the blood at birth. Those infected peripartum test negative for virus at birth but have virus detected by 2–4 weeks of age. Infant viremia rises steeply, as is also seen in adults reaching a peak at age 1–2 months. In contrast with adults, infants will have only a very gradual decline in plasma viremia that extends to age 4–5 years. Up to 50% of infants will have rapid disease progression to AIDS or death by age 2 years. Although this rapid progression is associated with high-level viremia, measurement of plasma virus and/or CD4 T-lymphocyte parameters do not identify all infants at risk for rapid progression.

Siewe B, Landay A: Key Concepts in the early immunology of HIV-1 infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2012 Feb;14(1):102–1029. doi: 10.1007/s11908-011-0235-3 [PMID: 22203492].

PERINATALLY HIV-EXPOSED INFANT

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Newborns with perinatal HIV infection are rarely symptomatic at birth, and there is no recognized primary infection syndrome in these infants. Physical features are not different from uninfected neonates. However, 30%–80% of infected infants have symptoms within the first year of life. Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, parotitis, and recurrent respiratory tract infections are signs associated with slow progression. Severe bacterial infections, progressive neurologic disease, anemia, and fever are associated with rapid progression. Early ARV therapy can slow or prevent disease progression. Hence, early diagnosis is critical and can be accomplished using laboratory testing during the first months of life.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Laboratory Diagnosis

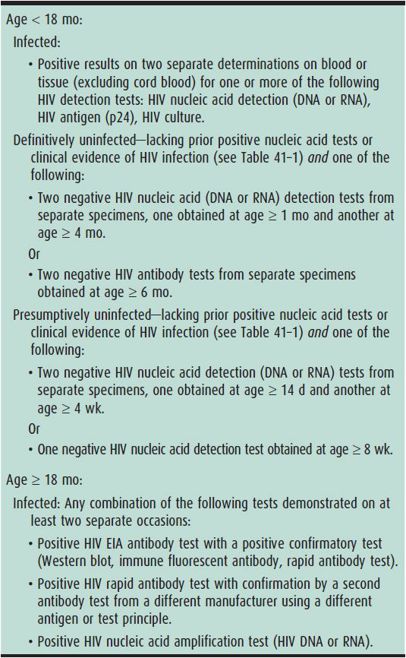

Infants born to HIV-infected mothers will have HIV antibody until 6–18 months of age, regardless of infection status, owing to transplacental passage of maternal antibody. Therefore, diagnosis must be made by direct detection of virus. Age-specific laboratory criteria defining infection status are outlined in Table 41–2. The preferred test for infant diagnosis is detection of HIV DNA or RNA in blood, collectively referred to as nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT). Positive HIV NAT at any age requires repeat testing for confirmation since false positives may occur. Positive HIV NAT on two occasions indicates HIV infection.

Table 41–2. Age-specific laboratory criteria defining infection status.

HIV NAT is positive in blood at birth for the fraction of infants infected in utero but negative for infants who acquire infection at birth. Almost all infected infants, with either in utero or peripartum acquisition, will have detectable HIV by 2 weeks of life and over 95% will have detectable virus by 4 weeks, allowing for early diagnosis. Thus, infection can be “presumptively” excluded by negative HIV NAT at age 2 and 4 weeks, in the absence of breast-feeding. Definitive evidence of absence of infection is defined by negative HIV NAT at greater than 1 and 4 months. After 12–18 months of age, for infants with negative HIV NAT, many clinicians will obtain HIV antibody testing to demonstrate reversion to seronegative status, thereby confirming the absence of infection.

Breast-fed infants may acquire HIV at any time until they are fully weaned, and virus may not be detected until as long as 6 weeks after the exposure. Therefore, breast milk–exposed infants should be retested at 6 weeks after their last exposure to identify or presumptively exclude infection.

Management and Outcome of the Perinatally HIV-Exposed Infant

Management and Outcome of the Perinatally HIV-Exposed Infant

HIV-infected infants have a high risk of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP), with the peak incidence at age 2–6 months. Thus, prophylaxis for P jiroveci pneumonia is given to infants born to HIV-infected mothers beginning at age 4–6 weeks. PCP prophylaxis may be deferred for infants who are demonstrated to be presumptively HIV-uninfected by age 6 weeks. Infants with ongoing HIV exposure via breast-feeding are recommended to continue PCP prophylaxis until HIV infection has been excluded after cessation of breast-feeding.

During the period of postnatal ARV prophylaxis, some infants have reversible anemia or neutropenia that is usually not clinically significant. Subsequently, children who have been exposed to HIV and to ARV drug prophylaxis (but who remain uninfected) are generally healthy. Ongoing studies have found alterations in some growth, neurocognitive development, immune, and organ function parameters, but their clinical significance is not yet known. Some studies have found symptoms consistent with mitochondrial toxicity; other studies have failed to confirm the findings. There is biological plausibility for this toxicity because the nucleoside analogue drugs used during pregnancy and postnatally to prevent transmission may cause mitochondrial toxicity. The issue remains controversial, but at present it is clear that the benefit of prenatal and postnatal treatment to prevent HIV transmission outweighs the potential risk. Ongoing studies are important to elucidate the affects of in utero and perinatal HIV and ARV exposure.

Burgard M et al: Performance of HIV-1 DNA or HIV-1 RNA tests for early diagnosis of perinatal HIV-1 infection during anti-retroviral prophylaxis. J Pediatr 2012;160(1):60–66 [PMID: 21868029].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Revised surveillance case definitions for HIV infection among adults, adolescents, and children aged < 18 months and for HIV infection and AIDS among children aged 18 months to < 13 years—United States, 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep 2008;57(RR-10):1–9 [PMID: 19052530].

Havens PL, Mofenson LM: Committee on Pediatric AIDS. Evaluation and management of the infant exposed to HIV-1 in the United States. Pediatrics 2009;123:175–187 [PMID: 19117880].

Nielsen-Saines K et al: ACTG 5190/PACTG 1054 Study Team: Infant outcomes after maternal antiretroviral exposure in resource-limited settings. Pediatrics 2012;129(6):e1525–1532. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2340 [PMID: 22585772].

ACUTE RETROVIRAL SYNDROME

Among adolescents and adults with primary acute HIV infection, nonspecific symptoms (eg, flu- or mild mononucleosis-like illness) beginning 2–4 weeks after exposure occur in 30%–90%, but they are frequently not severe enough to be brought to medical attention. This acute retroviral syndrome, with symptoms of fever, malaise, and pharyngitis, is often indistinguishable from other similar viral illnesses. Less common but more distinguishing features are generalized lymphadenopathy, rash, oral and genital ulcerations, aseptic meningitis, and thrush. In the early weeks after acute, behaviorally acquired infection, HIV antibody may be absent. Most patients will seroconvert by 6 weeks after exposure, but occasionally seroconversion does not occur for 3–6 months. When acute HIV infection is suspected, nucleic acid amplification tests will detect HIV infection. Additional information on behaviorally acquired HIV is found in Chapter 44.

Hecht FM et al: Use of laboratory tests and clinical symptoms for identification of primary HIV infection. AIDS 2002;16(8): 1119–1129 [PMID: 12004270].

Kinloch-de Loes S et al: Symptomatic primary infection due to human immunodeficiency virus type 1: review of 31 cases. Clin Infect Dis 1993;17(1):59–65 [PMID: 8353247].

PROGRESSIVE HIV DISEASE

A. Clinical Findings

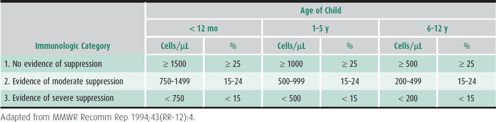

1. Disease staging—The CDC has developed disease staging criteria for HIV-infected children (Table 41–3; see Tables 41–1). The criteria incorporate clinical symptoms ranging from no symptoms to mild, moderate, and severe symptoms (categories N, A, B, and C, respectively) and immunologic categories 1, 2, or 3 (defined by age-adjusted CD4 T-lymphocyte counts) corresponding to no, moderate, or severe immune suppression, respectively. Each child’s disease stage is classified both by clinical and CD4 T-lymphocyte category. The WHO has established a similar clinical staging system that is used widely outside the United States (Table 41–4). Staging criteria characterize the degree of disease progression and are predictive of mortality risk for children older than 2 years who are not receiving ARV therapy. Disease stage is used in determining when to initiate ARV therapy.

Table 41–3. Immunologic categories based on age-specific CD4 T-lymphocyte counts and percentages of total lymphocytes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree