Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Young Women

Cathryn L. Samples

Introduction

Young people and, particularly, young women worldwide continue to be impacted by the HIV/AIDS pandemic, with 40% of the 2.3 million new annual infections in adults age 15 and older occurring in youth under the age of 25, and half of all HIV infections starting before age 25 (1,2). Half of the 31.3 million adults (age 15 and older) living with HIV worldwide are female (3), and in the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa, 53% and 59% are female, respectively (2). Access to needed antiretroviral treatment has increased in recent years, from 7% in 2003 to 42% in 2008, while the proportion of women able to access treatment for the prevention of maternal-to-child transmission (PMTCT) has grown from 10% in 2004 to 45% in 2008. Still, 430,000 children younger than age 15 and 920,000 15- to 24-year-olds are newly infected annually. Worldwide, HIV is spread primarily as a sexually transmitted disease. Not surprisingly, for women, community prevalence and access to primary care, treatment and diagnosis of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and reproductive health services including family planning and prenatal care are all closely related to HIV transmission risk, and to the likelihood of HIV testing and HIV care and treatment access. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that there are 56,300 new cases annually, with no recent decline in new infections (4). Young people (ages 13 to 29) accounted for 34% of those new infections over the past several years. There were an estimated 1.1 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States in 2006, 280,000 of them women, 61% of those black (5). In the past decade, there have been major advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis and natural history of HIV in children and adolescents and breakthroughs in antiretroviral treatment leading to improved morbidity and mortality and decreased perinatal transmission. With adolescents and young adults continuing to develop HIV, and youth born with HIV increasingly surviving to and beyond adolescence, the clinician caring for young women will need to be able to assess risk factors for acquisition; offer both routine screening for HIV and targeted HIV counseling, testing, and risk reduction advice; and consider HIV as part of the differential diagnosis for many signs and symptoms. Those providing health and reproductive health services to young women should be prepared to inform and provide initial care and referral resources for young women who test positive for HIV infection, to provide appropriate reproductive health care and counseling to girls and young women born with HIV, and to manage the routine and episodic health care and reproductive health care of adolescents and young adults with HIV infection acquired during or after puberty. This chapter updates current epidemiologic information, reviews new recommendations for HIV testing, describes the characteristics of AIDS and HIV infection in young women, and reviews recent developments in treatment and care. It also reviews recent guidelines impacting the treatment of women with or at risk of HIV. We discuss the clinician’s role in case finding, prevention, diagnosis, and management, and review the impact of HIV and its treatment on reproductive health, contraception, and pregnancy options. Recent developments and guidelines in antiretroviral treatment, primary care follow-up, and prevention of maternal-to-child and discordant partner transmission are discussed.

Epidemiology

Description of the HIV epidemic in adolescents in the United States relies on information from several sources: AIDS and HIV case reports, seroprevalence studies, surveys of risk behavior and of indicator diseases, mortality data, and voluntary testing data. AIDS case reporting was introduced in 1981, and HIV case reporting was introduced in 1985. After a CDC recommendation for universal name-based HIV reporting in 1994, all 50 states were reporting as of 2008, but only 37 states and 5 dependent areas had sufficient name-based data for accurate projections of new diagnoses by 2008. Data from those areas are used to estimate the number of people living with HIV (PLWH) or newly infected with HIV (incidence), as well as prevalence rates of HIV for particular populations. In 22 states, specialized blood assays (Serologic Testing Algorithm for Determining Recent HIV Seroconversion, STARHS) are used to identify recent infection, to aid annual incidence estimates. Back-calculation, serosurveillance, tests for new infection, measures of late diagnosis, and household surveys have been used to estimate the impact of health disparities and to better describe both new cases and the number of people living with HIV infection in the United States. All 50 states and 5 dependent areas will be counted in future surveillance reports (6).

AIDS Case Reports

A 1995 review of the first 500,000 cases of AIDS in the United States revealed an increase in the proportions of persons with AIDS who were female, persons of color, injection drug users, and alive at the time of the report (7). Since 1996, dramatic declines in both AIDS incidence and deaths have been reported. New AIDS cases have leveled at about 40,000 per year since 1999, with 39,202 cases reported in 2008 (5,8). Of the cumulative 45,683 individuals ages 13 to 24 years diagnosed with AIDS through 2007 in the United States, 10,887 were reported between 2003 and 2007, 32% of them female, and 28% of those young women were ages 13 to 19 years. Of cases reported in 2007, 40% of 13- to 19-year-old cases were female, and 25% of 20- to 24-year-old cases were female. Because the time from infection with HIV to the development of AIDS-defining conditions

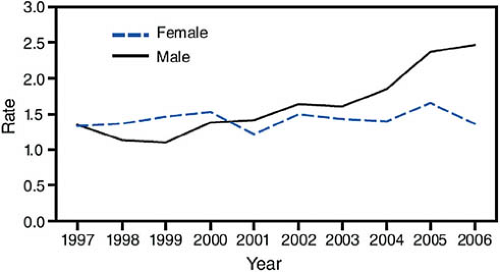

or criteria averages 5 to 10 years, even without treatment, almost all 20- to 24-year-olds with AIDS acquired their infection at birth or during childhood or adolescence, and most of the 13- to 19-year-olds reported with AIDS had perinatal infection. In the past 14 years, the advent of antiretroviral treatments and improved understanding of their use have produced marked decreases in mortality and improved survival and quality of life. Thus, AIDS case reporting gives little insight to current prevalence or recent trends in the spread of the virus among youth. Figure 19-1 maps the AIDS prevalence rates for 10- to 24-year-olds in the United States, and Fig. 19-2 shows the trends in new diagnosis rates by gender over time for 15- to 19-year-olds.

or criteria averages 5 to 10 years, even without treatment, almost all 20- to 24-year-olds with AIDS acquired their infection at birth or during childhood or adolescence, and most of the 13- to 19-year-olds reported with AIDS had perinatal infection. In the past 14 years, the advent of antiretroviral treatments and improved understanding of their use have produced marked decreases in mortality and improved survival and quality of life. Thus, AIDS case reporting gives little insight to current prevalence or recent trends in the spread of the virus among youth. Figure 19-1 maps the AIDS prevalence rates for 10- to 24-year-olds in the United States, and Fig. 19-2 shows the trends in new diagnosis rates by gender over time for 15- to 19-year-olds.

HIV and AIDS Diagnoses and Prevalence in Selected Areas

A somewhat more helpful picture of girls and young women known to have HIV can be obtained by examining data from recent reporting of new HIV diagnoses in the states and areas with name-based reporting by January 2005, which CDC uses for projecting new diagnoses. These states reflected 66% of all new AIDS diagnoses in 2007, when 6651 youth ages 13 to 24 years were diagnosed and reported with HIV/AIDS, 25% of them female (31% of the 13- to 19-year-olds, and 23% of the 20- to 24-year-olds). Most youth diagnosed with HIV were black (72% of 13- to 19-year-olds, and 61% of 20- to 24-year-olds) or Latino (13% and 18%, respectively). Between 2003 and 2007, 88% of teen girls and 87% of young adult women diagnosed with HIV/AIDS were in the high-risk heterosexual transmission category (9).

In 2006, 36% of all persons newly diagnosed and reported with HIV had AIDS at or within 12 months of their diagnosis, reflecting late diagnosis. Youth were more likely to be diagnosed early, with just 11% of children younger than 13 years, 20% of 13- to 14-year-olds, 14% of 15- to 19-year-olds, and 18% of 20- to 24-year-olds diagnosed late. These data, along with estimates of actual incidence, have been used to infer that 25% of the estimated 1.1 million adults and adolescents living with HIV in the United States do not know their diagnosis, and that a higher proportion of newly diagnosed youth have recent infection (10).

Estimates of HIV/AIDS Incidence and Prevalence in Youth/Young Women

A recent review of the sexual and reproductive health of 10- to 24-year-olds in the United States, which gathers HIV/AIDS point estimates from case reporting, vital statistics, surveys, and surveillance systems, estimated there were 22,000 10- to 24-year-olds living with HIV in the 38 areas with established surveillance systems as of 2006, 41% of them female (11). The annual AIDS diagnosis rate per 100,000 for all 50 states was 0.5 for 10- to 14-year-old girls, 0.8 for 15- to 17-year-old girls, 2 for 18- to 19-year-old young women, and 4.6 for 20- to 24-year-old young women, but lower than the rate among young men in all but the youngest age groups. CDC estimates that 31% of all new HIV infections in the United States occur in youth and young adults (age 13–29 years) (12). AIDS and HIV prevalence rates among youth are highest in the northeast and southern regions of the United States. Diagnosis and prevalence rates demonstrate persistent significant health disparities. Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to be diagnosed with HIV or living with HIV than whites in all youth age groups (11,13). Among young women ages 15 to 19 years, blacks were 17.3 times and Hispanics 5.4 times more

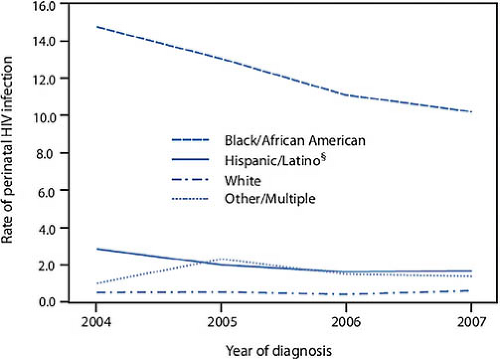

likely to be living with HIV, and 16.4 and 4.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than whites. Table 19-1 delineates these disparities for young women by age and ethnicity (12). The literature suggests that this increased risk of acquisition of HIV is separate from any behavioral risk. Similarly, the annual rate of perinatal infection in the United States, while declining, still reflects a disproportionate burden of HIV among black women (Fig. 19-3) (14).

likely to be living with HIV, and 16.4 and 4.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than whites. Table 19-1 delineates these disparities for young women by age and ethnicity (12). The literature suggests that this increased risk of acquisition of HIV is separate from any behavioral risk. Similarly, the annual rate of perinatal infection in the United States, while declining, still reflects a disproportionate burden of HIV among black women (Fig. 19-3) (14).

Table 19-1 Disparities in HIV/AIDS Rates per 100,000 Females by Race/Ethnicity: AIDS Rates for United States; HIV Rates for 38 Areas with Established Name Reporting, 2006 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

HIV Seroprevalence and Behavioral Risk Factor Studies

Early in the HIV epidemic, serosurveys using unlinked, blinded samples of blood obtained for surveillance or other reasons, or results of routine linked testing in special populations such as the military and Job Corps, helped to determine the prevalence of HIV among youth (15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30). Studies of homeless youth have shown seroprevalence rates ranging from 0.41% to 7.4% (16,19,20). Few studies have documented the rate of HIV in healthy adolescents, but the addition of HIV serosurveillance to the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health (Add Health) study’s third wave has produced exciting new information on seroprevalence (19). That study showed a seroprevalence of 1.0 per 1000 in the cohort of 13,184 eligible youth. Black non-Hispanic youth had significantly higher prevalence rates compared to youth of other races/ethnicities (4.9 vs. 0.22 per 1000). The study predicted that 15% to 30% of adult HIV prevalence had its origin before the age of 25.

Significant racial disparities in HIV incidence are seen in women, and a recent review suggests that the increased risk of HIV (20:1 for black vs. white women, and 4:1 for black vs. Hispanic women) is more related to race ethnicity and STI history of the woman and behavior of her male partner than to number of sexual partners and condom use (31).

Assessment

HIV Screening, Testing, and Risk Assessment

Specific HIV prevention counseling and offering of testing are essential components of both routine health care and reproductive health care for adolescents and young adults. Clinicians caring for young women should ask routinely about HIV status and be prepared to offer routine HIV screening to those who have not been tested, and target retesting to those at increased risk. In 2006, new CDC guidelines recommended opt-out screening for HIV as part of routine health care for all persons ages 13 to 64 years in U.S. communities with a seroprevalence of >1 per 1000 (10). Testing for HIV only in people who are symptomatic or members of previously defined risk groups is inadequate for both prevention and access to care and support, especially for

young women and for youth of color. Prior to 2006, CDC recommended that HIV testing should include informed consent, assessment of sexual behavior, substance use and abuse, and psychosocial issues, as well as attention to the skills needed for risk reduction and personal protection. Guidelines and recommendations were developed to address these issues in adolescents and adults (32,33,34). The 2006 guidelines grew out of concern that unlike maternal-to-child transmission and transmission by blood, blood products, and injection drug use, sexual transmission of HIV has not declined in the United States. CDC estimates that more than 50% of new sexually transmitted HIV is transmitted by the 252,000 to 312,000 people (20% of persons living with HIV in the United States) who do not yet know their status (35,36). When people are unaware of their status, they not only lack needed care (including treatment to lower viral load) but also are more likely to have unprotected sex and to inadvertently transmit HIV to partners (35,37). Antiretroviral therapy has produced dramatic declines in morbidity and mortality, and perinatal transmission has been dramatically reduced by identification and treatment of pregnant women and their infants. Transmission of HIV can also be reduced by testing and risk reduction counseling, especially among youth with recent infection, and new technologies have improved the ease of testing and the proportion of youth receiving their results (38). A 2003 CDC initiative focused prevention efforts on (a) the identification of people with HIV (by both routine offering of testing in clinical settings and outreach using rapid testing and other new technologies among those at high risk) and (b) increased efforts to promote reduced transmission risk by behavioral interventions for infected persons and prenatal screening (34,38,39). In the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), pregnant women were more likely to test than nonpregnant women (54% vs. 15%), but the National Health Interview Survey showed stagnant rates of lifetime and past-year testing among adults despite the 2003 recommendations (40). A 2009 survey showed no change in the proportion of 18- to 64-year-olds ever testing from 1997 to 2009, but 30% of 18- to 29-year-olds and nearly 50% of young adult African Americans reported testing in the past year (Fig. 19-4). The proportion of adults (17%) who report that an HIV test was ever suggested by their doctor increased for African Americans and Latinos (29% and 28%, respectively), but not for whites (14%) (41). Special efforts are still needed to promote a sense of risk and vulnerability and to aid access to care and testing among youth, and to target youth at increased risk for repeated testing and risk reduction effort, with the goal of earlier knowledge of status and access to treatment. In 2005, 40% of newly diagnosed persons had AIDS within a year of testing positive for HIV, suggesting delayed testing and access to care (36). Primary prevention and the universal provision in schools and health promotion programs of concrete skill-based prevention education, risk reduction, and access to effective contraception, as well as sexual health and substance abuse services, remain critical to prevention of new infections among youth.

young women and for youth of color. Prior to 2006, CDC recommended that HIV testing should include informed consent, assessment of sexual behavior, substance use and abuse, and psychosocial issues, as well as attention to the skills needed for risk reduction and personal protection. Guidelines and recommendations were developed to address these issues in adolescents and adults (32,33,34). The 2006 guidelines grew out of concern that unlike maternal-to-child transmission and transmission by blood, blood products, and injection drug use, sexual transmission of HIV has not declined in the United States. CDC estimates that more than 50% of new sexually transmitted HIV is transmitted by the 252,000 to 312,000 people (20% of persons living with HIV in the United States) who do not yet know their status (35,36). When people are unaware of their status, they not only lack needed care (including treatment to lower viral load) but also are more likely to have unprotected sex and to inadvertently transmit HIV to partners (35,37). Antiretroviral therapy has produced dramatic declines in morbidity and mortality, and perinatal transmission has been dramatically reduced by identification and treatment of pregnant women and their infants. Transmission of HIV can also be reduced by testing and risk reduction counseling, especially among youth with recent infection, and new technologies have improved the ease of testing and the proportion of youth receiving their results (38). A 2003 CDC initiative focused prevention efforts on (a) the identification of people with HIV (by both routine offering of testing in clinical settings and outreach using rapid testing and other new technologies among those at high risk) and (b) increased efforts to promote reduced transmission risk by behavioral interventions for infected persons and prenatal screening (34,38,39). In the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), pregnant women were more likely to test than nonpregnant women (54% vs. 15%), but the National Health Interview Survey showed stagnant rates of lifetime and past-year testing among adults despite the 2003 recommendations (40). A 2009 survey showed no change in the proportion of 18- to 64-year-olds ever testing from 1997 to 2009, but 30% of 18- to 29-year-olds and nearly 50% of young adult African Americans reported testing in the past year (Fig. 19-4). The proportion of adults (17%) who report that an HIV test was ever suggested by their doctor increased for African Americans and Latinos (29% and 28%, respectively), but not for whites (14%) (41). Special efforts are still needed to promote a sense of risk and vulnerability and to aid access to care and testing among youth, and to target youth at increased risk for repeated testing and risk reduction effort, with the goal of earlier knowledge of status and access to treatment. In 2005, 40% of newly diagnosed persons had AIDS within a year of testing positive for HIV, suggesting delayed testing and access to care (36). Primary prevention and the universal provision in schools and health promotion programs of concrete skill-based prevention education, risk reduction, and access to effective contraception, as well as sexual health and substance abuse services, remain critical to prevention of new infections among youth.

Indications for Testing

Beginning in 1995, the CDC issued and updated guidelines recommending routine HIV counseling and voluntary testing for all pregnant women, and the Institute of Medicine issued a strong 1999 report urging prenatal testing (10,42,43,44). Many states now mandate testing (some in both the first and third trimesters) for pregnant women or children born to women without recent HIV testing or lacking prenatal care. A compendium of state laws regarding prenatal, labor and delivery, and newborn screening is available online from the National HIV/AIDS Clinician Consultation Center (NCCC) (45). The same compendium is a valuable reference for state laws on informed consent for HIV testing and other HIV testing legislation. Written informed consent may be a barrier to testing according to one BRFSS study assessing testing rates in states with and without written informed consent requirements (46). Several states have modified their laws since the 2006 CDC guidelines recommended routine screening of 13- to 64-year-olds without the burden of counseling and written informed consent other than the general consent for care (opt-out screening). The CDC also recommended repeated targeted HIV screening or repeat testing in several other circumstances—high-risk behavior (retest at least annually), need for tuberculosis treatment, STI diagnosis and treatment or attendance at an STI clinic, pregnancy, and preconceptual care—and recommended offering testing to couples beginning a new

relationship, as well as targeted outreach and facilitated testing to communities with high prevalence or risk (10). The 2007 USPSTF guidelines recommended strongly that clinicians screen for HIV in all adolescents and adults at increased risk and all pregnant women, but made no recommendation for or against screening persons without increased risk (47). The American College of Physicians and the HIV Medicine Association published a clinical guidance statement on this issue after review of both CDC and USPSTF guidelines and cost-effectiveness studies in 2009. They recommended that all clinicians (a) adopt routine screening for HIV and encourage patients to be tested and (b) determine the need for repeat screening on an individual basis (48). Other organizations endorsing routine screening of all patients aged 13 to 64 years since 2006 include the American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Midwives, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Medical Association, and National Medical Association (49). The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine recommended the offering of testing and effective risk reduction counseling to all sexually active youth as part of routine health care, with protections to ensure confidentiality and minimize structural and financial barriers (50).

relationship, as well as targeted outreach and facilitated testing to communities with high prevalence or risk (10). The 2007 USPSTF guidelines recommended strongly that clinicians screen for HIV in all adolescents and adults at increased risk and all pregnant women, but made no recommendation for or against screening persons without increased risk (47). The American College of Physicians and the HIV Medicine Association published a clinical guidance statement on this issue after review of both CDC and USPSTF guidelines and cost-effectiveness studies in 2009. They recommended that all clinicians (a) adopt routine screening for HIV and encourage patients to be tested and (b) determine the need for repeat screening on an individual basis (48). Other organizations endorsing routine screening of all patients aged 13 to 64 years since 2006 include the American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Midwives, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Medical Association, and National Medical Association (49). The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine recommended the offering of testing and effective risk reduction counseling to all sexually active youth as part of routine health care, with protections to ensure confidentiality and minimize structural and financial barriers (50).

When new relationships, STIs, pregnancy, or preconception counseling prompt testing, HIV testing of sex partners should be encouraged and available on site or by referral. It is important to assess the timing of potential risk exposure and to recommend consistent condom use for both partners, as well as repeat testing if an initial test is negative and there was significant recent risk. The care provider must be aware of applicable state laws regarding HIV testing, consent, confidentiality, release of information, and reporting, as well as available sources of anonymous and/or free testing (45). Most states either have specific laws or policies allowing adolescents to access testing without parental or guardian consent or the right to testing is assumed to be part of a youth’s right to confidential STI diagnosis and treatment. Testing of children younger than age 13 usually requires parent or guardian consent, but assent and education may be needed for the pubertal child.

Screening and Testing for HIV: Barriers and Facilitators

Young women are more likely to accept or seek HIV testing if encouraged by their clinician (51). The CDC recommends screening of all youth at least 13 years of age, but if resources and privacy limit this practice, at a minimum all sexually active adolescents should routinely be asked their HIV status, and that of their partner(s), and receive information about HIV testing from their health care providers (50). If there is no documentation of maternal HIV status, youth who are adopted or orphaned or have a history of sexual assault or abuse can also be offered routine testing. In practice, the offering and provision of routine testing by clinicians is sometimes impaired by concerns about confidentiality, billing codes, lack of health insurance coverage, documentation, and stigma, as well as by the ever-present limitation of time to provide the information needed. The American Medical Association and American Academy of HIV Medicine have collaborated to compile useful Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for routine HIV testing, rapid testing, and related visits in health care settings. The guide is available online, along with links to care resources (52).

The presence of a parent or guardian in the room at the visit of a teen or young adult may also pose a significant barrier to privacy for the patient; this can be addressed by ensuring each young woman has time alone with the clinician during the visit and that her parents understand practice confidentiality protocols. The care provider must be aware of applicable state laws regarding HIV testing, consent, confidentiality, release of information, and reporting, as well as available sources of anonymous and/or free testing that are appropriate and accessible for youth. Most states either have specific laws or policies allowing minor adolescents to access testing without parental or guardian consent or the right to testing is assumed to be part of a youth’s right to confidential STI diagnosis and treatment; a compendium of state HIV testing Laws, available at http://www.nccc.ucsf.edu/, addresses state-specific variations (45). The Web site http://www.HIVTest.org can readily help youth and their clinicians to identify local testing resources by allowing them to plug in the zip code of the residence, school, or practice, and resources can also be found by text messaging. Some offices train nursing or family planning or health educators to assist in this task or offer rapid or noninvasive testing in clinics and nonmedical settings for at-risk youth. Partnership with local health departments or other publicly funded testing programs may also aid in referrals for testing for youth hesitant to access testing at their primary care site.

For routine HIV testing, results of a reactive or positive standard HIV enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody test (blood or oral mucosal transudate [OMT], OraSure) should not be given until the result of the confirmatory test (usually a Western blot done on the same specimen) returns, as a positive ELISA with negative Western blot is a negative test. OMT testing is noninvasive and accurate, has sensitivity (99.9%) and specificity (>99.9%) comparable to serum testing, and has proved to be a useful technique for youth with needle phobia or in nonclinical settings, but like regular HIV testing it is limited in scope in non–primary care settings as the proportion of youth returning for results may be inadequate. Rapid screening for HIV antibody has recently become widely available. Several rapid tests now have a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) waiver as a point-of-care test, and may be done on venous, fingerstick, or oral samples in 10 to 30 minutes. Rapid tests are preliminary (ELISA only) and require prompt confirmation by a standard blood HIV test if reactive or positive. In the developing world, a second rapid test technology is often used to confirm a reactive rapid test, given the high sensitivity and specificity of these tests in high-prevalence populations (53). Rapid tests are increasingly being used in labor and delivery (when a pregnant women has no documentation of HIV testing), emergency rooms, urgent care, family planning, obstetric and STI programs, and dental practices, as well as in juvenile justice and correctional detention programs, homeless shelters, adolescent clinics, and mobile health vans and other community-based venues promoting knowledge of status in high-prevalence areas (54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63). Although rapid, these point-of-care tests require staff training and rigorous quality control in compliance with local public health and CLIA waiver standards. Our own large urban adolescent clinic began rapid testing for both patients and others walking into our publicly funded testing site in 2008. We found that more than 90% of youth preferred the rapid fingerstick option over both venous and OMT tests, with a 5- to 14-day wait for test results, especially if they otherwise did not require phlebotomy, and both the number of test clients and the number

and proportion learning their HIV status increased (64). Testing in health settings should always be voluntary, even if state laws allow the opt-out approach, with verbal informed consent by the adolescent or young adult patient documented in the medical record if written consent is not required. Recommendations for pre- and post-test counseling have been dramatically simplified in the context of routine screening, with variable state interpretations. Young women presenting initially with a parent may require extra time or a separate visit to address HIV screening confidentially, once made aware it is available. Patients agreeing to testing should be informed of what will happen or what you will advise if their result is positive, negative, or indeterminate; how the test will (or will not) be documented; and the HIV name reporting and any partner or parental notification requirements in the practice jurisdiction. Although risk assessment prior to each HIV test is not required by the CDC recommendations, risk assessment and preventive counseling are an important component of routine and urgent care for young women. Indeed, the USPSTF recommends intensive behavioral counseling (within the primary care practice or by referral) of all sexually active adolescents (and adults at increased risk) as an important and effective component of STI prevention in clinical care (65,66). Brief counseling around either rapid or routine HIV testing can be an effective prevention intervention for all STIs, including HIV. If testing is also encouraged or available to partners, it creates an additional incentive for negotiating safer sexual relationships. A modular “Advise, Consent, Test, Support” tool kit for training staff and implementing brief, office-based testing for adolescents is available online at http://www.adolescentaids.org/healthcare/acts.html (67).

and proportion learning their HIV status increased (64). Testing in health settings should always be voluntary, even if state laws allow the opt-out approach, with verbal informed consent by the adolescent or young adult patient documented in the medical record if written consent is not required. Recommendations for pre- and post-test counseling have been dramatically simplified in the context of routine screening, with variable state interpretations. Young women presenting initially with a parent may require extra time or a separate visit to address HIV screening confidentially, once made aware it is available. Patients agreeing to testing should be informed of what will happen or what you will advise if their result is positive, negative, or indeterminate; how the test will (or will not) be documented; and the HIV name reporting and any partner or parental notification requirements in the practice jurisdiction. Although risk assessment prior to each HIV test is not required by the CDC recommendations, risk assessment and preventive counseling are an important component of routine and urgent care for young women. Indeed, the USPSTF recommends intensive behavioral counseling (within the primary care practice or by referral) of all sexually active adolescents (and adults at increased risk) as an important and effective component of STI prevention in clinical care (65,66). Brief counseling around either rapid or routine HIV testing can be an effective prevention intervention for all STIs, including HIV. If testing is also encouraged or available to partners, it creates an additional incentive for negotiating safer sexual relationships. A modular “Advise, Consent, Test, Support” tool kit for training staff and implementing brief, office-based testing for adolescents is available online at http://www.adolescentaids.org/healthcare/acts.html (67).

Giving positive or indeterminate HIV test results may have a serious impact and requires face-to-face counseling time, in addition to clear instructions on future risk reduction and future testing. Information and support may need to be provided over several visits. Many HIV-positive youth go through a period of denial during which they are unable or unwilling to seek care. Discussion of treatment and care options as part of the routine or diagnostic testing process and involvement in ongoing medical care may promote the decision to test, the receipt of results, and rapid baseline evaluations to assess prognosis and assist entry to ongoing HIV care.

Prenatal Screening for HIV

CDC guidelines recommending testing of all pregnant women for HIV infection were developed in response to the 1994 results of Protocol 076 of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (42,68). In this trial, treatment of asymptomatic pregnant women with zidovudine beginning in the second trimester as well as intrapartum intravenously, and 6-week treatment of the newborn with oral drug resulted in a highly significant drop in transmission rates to the infants of the treated mothers (from 25.5% to 8.3%). Routine prenatal testing as early as possible in pregnancy, usually as part of the prenatal panel at the initial visit, should now be a standard approach, with repeat testing or rapid testing in the third trimester recommended (or in some cases required by law) in high-prevalence locations and circumstances (10). Rapid test offering increases compliance with prenatal outpatient testing (10,57,62). In addition, rapid testing should be available to be offered at labor and delivery to any woman lacking documentation of prenatal HIV status conforming to state law (56,69). Identification of HIV infection in women during or prior to pregnancy is critical to Prevention of Maternal to Child Transmission (PMTCT) globally. Breastfeeding is currently contraindicated in HIV-positive women in developed countries, and should also be discouraged if the young woman and her partner(s) have not been HIV tested. The use of antenatal zidovudine and the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and combination therapy to improve effective viral suppression, combined with treatment of the exposed infant, has dramatically reduced perinatal infection and led to rapid reduction in the incidence of perinatal transmission to <2% in the United States, lower if the viral load can be effectively controlled, although racial and ethnic disparities still exist (Fig. 19-3) (70). Current principles and guidelines for PMTCT and scenarios for treatment of newly diagnosed pregnant women and their offspring are discussed in Tables 19-2a and 19-2b. In the United States, even women not requiring antiretroviral therapy are treated with HAART combination therapy including or one or more NRTIs with good placental passage, but zidovudine monotherapy is not recommended (89). Care of young women who are pregnant or seeking pregnancy (or not using effective contraception) and their partners should incorporate this information about PMTCT. Preconceptual care and counseling of women living with HIV or HIV discordant or concordant couples is also addressed in the Perinatal Guidelines (89).

A negative HIV test early in pregnancy does not eliminate the possibility of recent or future antenatal infection, so partner testing is important, and repeat testing of the pregnant woman and/or continued condom use is recommended if the partner’s serostatus is positive or unknown or his risk high, or if recommended or required by specific states. Young women presenting in labor with no prenatal care or no prenatal HIV test can receive HIV testing by a rapid point-of-care testing method, and then receive intrapartum treatment to prevent transmission if it is reactive, while awaiting confirmatory testing results.

Diagnosis

The goal of HIV screening as well as testing based on risk is to enable early diagnosis of HIV infection, to prevent development

of opportunistic infections and immunodeficiency characterizing AIDS. However, there are many opportunities in the care of young women for diagnosing new or established HIV infection or AIDS. Routine health care, urgent care, immunization updates, family planning and reproductive health services, gynecologic care, emergency department visits, hospitalization, and diagnosis and treatment of STIs all offer opportunities for testing, as well as for risk assessment and preventive counseling. Young people diagnosed with HIV are often quite recently infected, as shown in an Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) study using a sensitive/less sensitive detuned assay to differentiate recent (<180 days) from established infection. In that study, 33% of 12- to 24-year-old youth presenting to care had recent infection (71). Regardless of duration of infection, some youth are tested and diagnosed because of a clinical history or presentation suggesting acute retroviral syndrome. Some may have symptoms suggesting established HIV or immunodeficiency, while others may be well but have concerning histories or risk, or be screened as part of routine care.

of opportunistic infections and immunodeficiency characterizing AIDS. However, there are many opportunities in the care of young women for diagnosing new or established HIV infection or AIDS. Routine health care, urgent care, immunization updates, family planning and reproductive health services, gynecologic care, emergency department visits, hospitalization, and diagnosis and treatment of STIs all offer opportunities for testing, as well as for risk assessment and preventive counseling. Young people diagnosed with HIV are often quite recently infected, as shown in an Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) study using a sensitive/less sensitive detuned assay to differentiate recent (<180 days) from established infection. In that study, 33% of 12- to 24-year-old youth presenting to care had recent infection (71). Regardless of duration of infection, some youth are tested and diagnosed because of a clinical history or presentation suggesting acute retroviral syndrome. Some may have symptoms suggesting established HIV or immunodeficiency, while others may be well but have concerning histories or risk, or be screened as part of routine care.

Table 19-2a Recommendation for Elimination of Perinatal Transmission | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 19-2b Clinical Scenario Summary Recommendations for Antiretroviral Drug Use by Pregnant HIV-Infected Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission of HIV-1 in the United States | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|