Hospice and Palliative Care

Julie Hauer, Barbara L. Jones, and Joanne Wolfe

Palliative care is a model of interdisciplinary care that seeks to improve the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness. This care includes the prevention and relief of suffering by promptly identifying and treating pain and other problems, whether they are physical, psychosocial, or spiritual.1,2 To assist in identifying and addressing these sources of suffering, interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care teams often include a palliative care physician, advanced practice nurse, chaplain, social worker, and child life specialist. Hospice and Palliative Medicine is now a recognized medical subspecialty with trained medical experts. The preceding chapter (Chapter 125) discusses many of the principles of communication and care employed during hospice and palliative care. This chapter is more focused on the practice aspects of the development of a care plan.

PLANNING CARE

DISEASE TRAJECTORY AS A GUIDE TO TIMING OF PALLIATIVE CARE

Different illness trajectories (or expected life trajectories) guide the timing of incorporating the principles of palliative care into clinical management.3,4

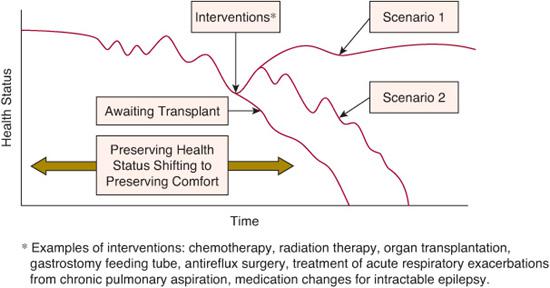

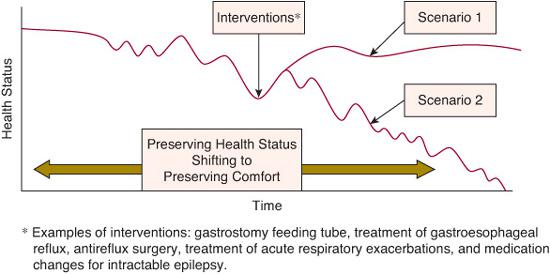

Life trajectory categories appropriate for palliative care consultation include the following: (1) Those where treatment is possible but may fail such as neoplasms not responding to conventional protocols, stem cell transplant, organ transplantation (see Fig. 126-1). (2) Those requiring intensive long-term treatment aimed at maintaining the quality of life such as progressive respiratory failure (eg, muscular dystrophy or cystic fibrosis), requiring assisted ventilation (see Fig. 126-2). (3) Those with a severe disability causing vulnerability to health complications and characterized by recurrent illness, hospitalizations, and decline in health and function.

FIGURE 126-1. Children with cancer awaiting organ transplant, or with severe developmental impairment.

Palliative care consultation can be useful for counseling and symptom management at any time in such children’s life trajectory. Specific symptom management strategies are discussed later in this chapter.

BENEFIT OF EARLY INTEGRATION

Uncertainty of prognosis has been identified as the most common barrier to palliative care and optimal end-of-life care for seriously ill children.10 Growing evidence demonstrates that families of children with cancer benefit from palliative care at these times of uncertainty.11-15 Earlier introduction of palliative care assures use of interventions to address physical and emotional suffering11 and is considered helpful by parents even when that information is upsetting.12 Though medical teams often worry that families are not ready, evidence demonstrates that integration of palliative care does not lessen parents’ hope.13

It is often challenging for physicians to initiate conversations about poor prognosis. Yet the majority of parents of children with cancer say they want prognostic information.12 Components identified by families as high-quality medical care included physician communication about what to expect in the end-of-life care period and well-prepared parents for whatever the outcome may be.14 Discussions that allow parents to prepare provides positive benefit to later bereavement.15 Patients and families who are poorly prepared tend to choose more aggressive care at the end of life.11,16 Half of bereaved family members of adult cancer patients indicated that palliative care was provided too late in the disease course, whereas fewer than 5% thought palliative care referrals occurred too early.17

PALLIATIVE CARE TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

Defining goals of care is a critical part of guiding decision making by identifying interventions and care that meet identified goals rather than treat a medical problem in isolation. Palliative care recognizes that it is distressing for parents and physicians to encounter the limits of medicine. At such times, physicians and families often do more out of a sense that they need to do something. Palliative care identifies other care options such as symptom management. Medical treatment and palliative care are ideally integrated together for children with serious illness.6,27,28 Areas of assessment in palliative care include eliciting a patient and families understanding of the disease course and searching for unmet emotional, psychosocial, and spiritual needs.29Chapter 126 discusses many of the concepts and tools used to engage with a family in the creation of a plan of care. A systematic approach to this process is described below. Communication tools used for this purpose are reviewed in eTable 126.1  .

.

FIGURE 126-2. Children with severe developmental impairment prognosis and uncertainty: Hope for the best, prepare for the rest.

PALLIATIVE CARE REQUIRES AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

PALLIATIVE CARE REQUIRES AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

Palliative care is only possible with an interdisciplinary team.6,29 Individual areas of expertise are critical to managing the multidimensional needs encountered by children and families.

• Social workers provide psychosocial assessment and supportive counseling for the child and family adjusting to changes along with identifying community services.

• Child life specialists provide skills in facilitating communication with children through activities that assist with emotional distress.

• Chaplains support faith traditions and spiritual values that promote healing and hope and support families as they face change, loss, or grief.

• Physicians and advanced practice nurses bring expertise in symptom management and serve as mediators between the medical teams and families.

CREATING A PLAN OF CARE

CREATING A PLAN OF CARE

Identifying shared goals is a beneficial place to start. For parents of children with serious illness at a time of uncertainty, this can include acknowledgment that everyone continues to hope for the best outcome possible. From there, parents can often guide physicians and team members by sharing their story. Team members can then reflect on what has been communicated and ask for clarification if necessary:

• Please share with me what the past few weeks or months have been like and what you understand about your child’s health status.

• What are you anticipating? What are you worrying about?

• Can you share what this has been like for you?

Parents often feel they need to focus on how well their child will do so they do not appear to be giving up. This can give the impression of not understanding how serious things are. However, parents often understand what the physicians are saying but find it hard to talk about the possibility of ongoing decline or death.

The best guide to future decisions includes defining what can be expected from current treatment available and a reflection on the benefit of past treatment. It allows physicians to consider what is likely to happen (probable) and what may happen (possible). Questions to consider and review to assist with this reflection include:

• Have goals of care been identified as a guide to decisions?

• Have options that meet these goals been offered or have medical interventions been presented as “needed,” “recommended,” or “necessary” for the problem identified?

• Will the intervention benefit the whole patient or manage a problem in isolation?

• How will the course look with or without the treatment available?

• Will an intervention bridge to the identified goals, such as maintaining or improving comfort and quality of life?

• Will an intervention provide sufficient recovery or prolong a process?

• Do we continue to see a benefit from chronic and acute treatment options with maintenance or return of health and functional status?

• Are we seeing less benefit from chronic and acute treatment over time with less return to prior baseline, longer periods of illness, or a shorter time between each illness?

• What percent of each day or week is “good” or “quality” time, and how does that compare to 1 year ago, 6 months ago, 1 month ago, and today?

• What percent of each day or week is there suffering?

• Will the interventions being considered maintain or improve health or will they prolong a process of decline or suffering?

• How much is the child able to enjoy relationships and activities and engage with loved ones?

In the process of decision making and defining a care plan, certain steps can help determine next steps if the benefit hoped for from an intervention does not occur:

• Define with the family the goals that you intend to meet.

• Identify the likelihood of an intervention meeting these goals.

• Know the evidence for the possible benefit and harm for the interventions available.

• Define a time period in which the intervention would be expected to meet the goal.

• Discuss a plan if the hoped for benefit does not occur in this time period or if increased suffering occurs (defining end points and anticipating an “exit strategy”).

Examples applying these strategies in the setting of an oncology patient and a child with severe developmental disability are provided in the electronic content.

RESUSCITATION STATUS AND OTHER ASPECTS OF ADVANCE CARE PLANNING

RESUSCITATION STATUS AND OTHER ASPECTS OF ADVANCE CARE PLANNING

When discussing resuscitation, it is important to assume responsibility for this assessment and not to imply parental responsibility for any outcome. It is helpful to discuss anticipated life-threatening events and to consider whether an intervention will reverse the primary problem or whether the event is a result of a problem that cannot be reversed or improved. This is in contrast to asking parents if they wish their child to be resuscitated; asking implies offering something that would benefit the child and shifts the decision-making burden to the parents.

DOCUMENTING, COMMUNICATING, AND COORDINATING PLANS OF CARE

DOCUMENTING, COMMUNICATING, AND COORDINATING PLANS OF CARE

Great care is only possible when critical information is determined, documented, and communicated to those involved in the child’s care. Areas of need discussed throughout this chapter that are an important part of this process include:

• Locations of care: this includes location of medical care (clinics, hospitals, and emergency service systems) and the community in which the child lives (home, respite care, school, and times of community based transportation)

• Individuals involved in the child’s care: family, health care proxy, home care nurses, providers of care in foster care or group homes, school nurses and teachers, respite care providers, bus drivers, health care teams and palliative care/hospice teams

• Information to include in documentation: goals of care and how these goals guide decisions, heath care and symptom management plans that meet these goals, location of health care for acute illness, resuscitation status, care plans for home and school in the event of a life-threatening event, contact information for individuals to assist at times of acute events

SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT FOR COMFORT

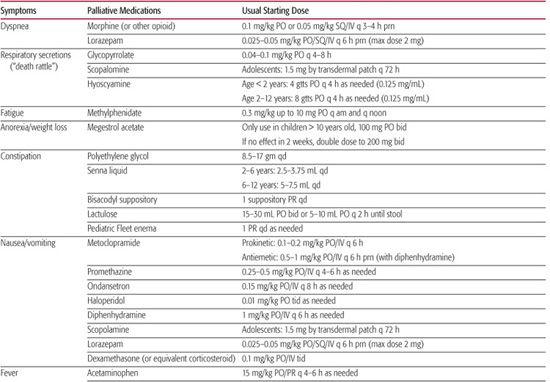

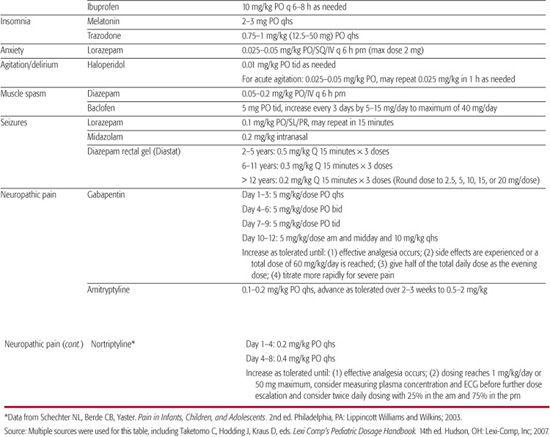

Symptoms commonly identified in children with cancer include pain, fatigue, dyspnea, decreased appetite, gastrointestinal problems (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea), delirium, depression, and anxiety.61,62 Medications commonly used for treatment of these symptoms are shown in Table 126-1. Similar symptoms have been identified in studies that have included children with neurodevelopmental impairment63 or focused exclusively on such children.64,65

PAIN ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

PAIN ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

The assessment and management of pain is discussed in Chapter 113. The discussion below is focused on the management of pain in the child a chronic condition requiring palliation.

Pain Assessment in Children with Chronic Conditions

Pain is assessed through either self-report or observational assessment. Assessment that utilizes reporting and rating of pain must be appropriate to the child’s cognitive level. Understanding of the child’s functional level should be sought from parents and caregivers, often indicated as a developmental age. Clinicians should use a validated pain rating system appropriate for the level of intellectual function.

Pain assessment tools involve the concept of placing and understanding things in order of magnitude. Children from age 5 or 6 are developing the ability to create a series in order of size. Pain rating tools appropriate for this functional age include poker chips and Oucher.66 Children from ages 7 to 10 can more reliably use tools to quantify pain, such as the Wong-Baker faces pain rating scale.67 Adolescents develop the ability to use a numerical rating scale, such as a 0 to 10 scale to rate their pain without the use of a tool.

Younger children or children with developmental disabilities may have an ability to indicate the presence, location and severity of pain but this depends upon their cognitive skills. Observational tools have been developed for use in non-verbal children or those unable to report pain. Specific distress behaviors have been associated with pain and are very helpful in quantifying pain in children unable to provide self-report. Behavioral measurement must be assessed in the context of sources of distress, since it may be difficult to distinguish between pain behaviors and behaviors resulting from other types of distress, such as hunger or anxiety.68

Table 126-1. Medications Used for Palliative Treatment of Common Symptoms (maximum weight 50 kg)

Observational Tools These assess vocalizations, facial expression, consolability, interactivity, mood, eating and sleeping, protective actions, movement, tone and posture, and physiological measures. When assessing children with severe to profound cognitive impairment, it is important to note that they were identified to have elevated scores at baseline on two pain assessment scales.69

The FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability)71 assessment tool provides a simple consistent method of pain assessment in nonverbal or preverbal children. The FLACC tool was revised (r-FLACC) to include behaviors specific to children with cognitive impairment.72 The Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist-Revised (NCCPC-R)73,74 is a standardized pain assessment tool for children with severe cognitive impairment. It is validated to be significantly related to pain intensity ratings provided by caregivers, consistent over time, sensitive and specific to pain, and demonstrated as effective for different levels of cognitive impairment.69,73,74 Although it provides a comprehensive pain assessment method for children with intellectual disability it is cumbersome for frequent pain assessment in the clinical setting. The Pediatric Pain Profile (PPP)75,76 is a 20-item behavior-rating scale designed to assess pain in children with severe to profound cognitive impairment that is available to download from the web following registration at www.ppprofile.org.uk. The Individualized Numeric Rating Scale (INRS)77 is a tool designed to incorporate parents’ knowledge of their cognitively impaired child’s pain expression.

Characterization of Pain

Pain is usually classified as either somatic nociceptive pain, caused by stimulation of intact nociceptors as a result of tissue injury. This can be a result of somatic pain, which is caused by stimulation of nociceptors in skin, soft tissue, skeletal muscle, and bone; nociceptive visceral pain, caused by stimulation of nociceptors and stretch receptors in the viscera; and neuropathic pain, caused by stimulation or abnormal functioning of damaged sensory nerves. Nociceptive somatic pain is well localized, and usually described as sharp, aching, squeezing, stabbing or throbbing. Visceral nociceptive pain is poorly localized and often described as dull, crampy or achy. Neuropathic pain is usually described as burning, shooting, or tingling.

Disease-related sources of pain may include nociceptive somatic pain from bone metastases or tumor; nociceptive visceral pain, such as from cholelithiasis or bowel distension; and neuropathic pain from tumor infiltration of peripheral nerves. Treatment-related pain may include mucositis and neuropathic pain.

The degree of pain experienced following a stimulus varies markedly within and among individuals. Previous pain exposure modulates responses such that one can either increase of decrease the pain response to a specific stimulus. The mechanisms controlling individual pain responses include differences in central pain processing functions that vary with previous life events, descending inhibition of pain transmission within the spinal cord and periphery, and a host of other factors. Thus, in one individual, the same stimulus may result in varied responses at different times.

Children with neurological impairment experience pain more frequently than the general pediatric population.78-81 Identifying a source of pain in a nonverbal child with a developmental disability poses a unique and significant challenge. Common recognized pain sources in these children include acute sources, such as fracture, urinary tract infection, or pancreatitis; and chronic sources, such as gastroesophageal reflex (GER), constipation, feeding difficulties from delayed gut motility, positioning, spasticity, hip pain, or dental pain. eTable 126.2  outlines etiologies of acute and chronic pain to consider.

outlines etiologies of acute and chronic pain to consider.

A source of pain may not be identified. Greco et al82 described the disorder of “Screaming of unknown origin” to indicate children with neurologic disorders, severe developmental delay, neurodegeneration, or severe motor impairments with persistent agitation, distress, or screaming. Evaluation often cannot identify a specific nociceptive cause of the pain.83 Breau et al79,84 identified gastrointestinal as the most frequent source described for episodes of pain in children with severe cognitive impairment.

Houlihan et al80 reported significantly higher rates of pain in children with a gastrostomy tube and those taking medications for feeding, gastroesophageal reflux, or gastrointestinal motility. This association may be due to the nonspecific nature of symptoms and signs but in the absence of other findings, it is reasonable to consider the hypothesis that this type of pain and may include a component of hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to painful stimuli) or allodynia (pain induced by nonpainful stimuli). These patients potentially could benefit from therapy with treatments utilized for neuropathic pain85 (see Chapter 113).

MANAGEMENT OF PAIN

MANAGEMENT OF PAIN

General Principles

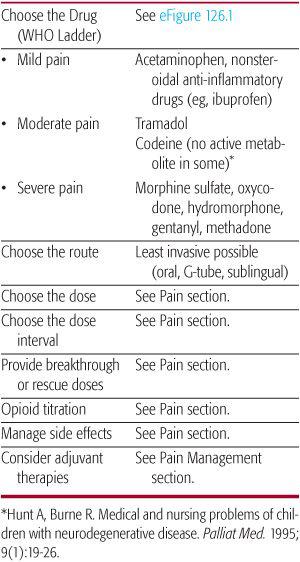

The World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder (eFig. 126.1  and Table 126-2) provides general guidelines for choosing the drug based on the degree of pain. When managing chronic pain several caveats should be considered. Nonopioids used for mild pain often can be used as adjuvant therapy when using opioids for moderate to severe pain. Codeine is ineffective in approximately one third of individuals due to a lack of metabolism to morphine.90 Meperidine should not be avoided for chronic use, particularly in those with reduced renal or hepatic function, because its metabolite can cause seizure. Methadone pharmacodynamics is complex confounding its chronic use. In addition, one should be aware that other adjuvant therapies can be used at any point on the analgesic ladder, especially for those with neuropathic pain (see Chapter 113 and Table 113-3). Other therapies including Complementary and Alternative Medicine approaches such as guided imagery, meditation, hypnosis, storytelling, music, art therapy, acupuncture may all be useful (see Chapter 14). Acupuncture, hypnosis, and mind-body therapies have proven efficacious interventions for pain and anxiety in children.96,99,100 Hypnosis specifically has been effective in lessening procedural distress, reducing procedural time, and reducing procedural pain and anxiety for children.96,101

and Table 126-2) provides general guidelines for choosing the drug based on the degree of pain. When managing chronic pain several caveats should be considered. Nonopioids used for mild pain often can be used as adjuvant therapy when using opioids for moderate to severe pain. Codeine is ineffective in approximately one third of individuals due to a lack of metabolism to morphine.90 Meperidine should not be avoided for chronic use, particularly in those with reduced renal or hepatic function, because its metabolite can cause seizure. Methadone pharmacodynamics is complex confounding its chronic use. In addition, one should be aware that other adjuvant therapies can be used at any point on the analgesic ladder, especially for those with neuropathic pain (see Chapter 113 and Table 113-3). Other therapies including Complementary and Alternative Medicine approaches such as guided imagery, meditation, hypnosis, storytelling, music, art therapy, acupuncture may all be useful (see Chapter 14). Acupuncture, hypnosis, and mind-body therapies have proven efficacious interventions for pain and anxiety in children.96,99,100 Hypnosis specifically has been effective in lessening procedural distress, reducing procedural time, and reducing procedural pain and anxiety for children.96,101

Table 126-2. General Guidelines to Pain Management

Safe and Effective Use of Opioids

Commonly used opiod medications and dosing is shown in Table 113-2. Opioids are the most effective agents for management of discomfort and pain. However, fear of the development of respiratory depression or addiction remains a barrier to the appropriate use of opioids, even at the end of life. This is unwarranted as opioid-induced respiratory depression is unlikely with appropriate dosing and titration, when adjusted for renal or hepatic impairment, and if titrated in a standardized manner in individuals with altered mental status or compromised respiration. When used appropriately and for stated goals, opioids do not hasten death but can assure comfort throughout life.

Unless pain is infrequent, an opioid should be given scheduled around the clock (ATC) based on the duration of analgesic effect of the specific opioid, typically every 4 hours. Once the opioid requirement is determined it can be converted to a sustained release given two or three times daily with immediate release used as needed for breakthrough pain. A reasonable trial dose for breakthrough pain is 10% of the 24-hour opioid requirement. It can be given as often as every 1 to 2 hours to achieve pain relief. Based on the patient response and the requirement for breakthrough analgesia, the daily dose of analgesics may be increased by 25–50% per day until adequate analgesia is achieved, or until there are intolerable or unmanageable side effects. For most opioids there is no fixed upper limit for the effective dose. It is beneficial to use the same opioid for sustained release and immediate release as it facilitates estimation of opioid requirement and eliminates confusion as to the source of opioid side effects. In renal impairment, fentanyl and methadone are considered the safest, oxycodone and hydromor-phone should be used with caution, and morphine sulfate should be avoided.91,92

Opioid side effects are common (see eTable 126.3  ) and management of these is important to assure continued use of necessary analgesics. Laxatives should be initiated when opioids are prescribed to prevent constipation. For many other side effects, such as sedation and nausea, symptom improvement may occur without dose adjustment after several days.

) and management of these is important to assure continued use of necessary analgesics. Laxatives should be initiated when opioids are prescribed to prevent constipation. For many other side effects, such as sedation and nausea, symptom improvement may occur without dose adjustment after several days.

Use of sustained release options in children is often limited by route of administration and required dosage. Methadone is an important long-acting option given its availability as a liquid. However, titration of methadone can be complicated given its rapid distribution phase (half-life 2–3 hours) followed by slow elimination phase (half-life 4.2–130 hours).87,103 This extended elimination phase may result in drug accumulation and toxicity 2 to 5 days after starting or increasing methadone.

When switching from one opioid to another, it is important to use a dose 25% to 50% lower than the calculated equivalent analgesic dose and then increase as needed, to avoid possible overmedication. Equivalent dosing information is shown in eTable 126.4  . For a systematic approach to management of escalating symptoms see eTable 126.5

. For a systematic approach to management of escalating symptoms see eTable 126.5  .

.

MANAGING OTHER SYMPTOMS

Dyspnea

Dyspnea is the experience of shortness of breath, difficulty of breathing, or painful breathing. It is a common symptom of numerous medical disorders including pulmonary parenchymal and obstructive disorders, neuromuscular disease, congestive heart failure, weakness and chest wall disorders (see Chapter 505). Measures of respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, blood gas levels, and family perception do not necessarily correlate with the patient’s perception of breathlessness.

Treating dyspnea is typically focused on identifying and aggressively treating the underlying cause. If dyspnea persists despite maximal medical management of identified causes, interventions include an oxygen trial, cool air from a fan or open window, repositioning, hypnosis, lorazepam for associated anxiety, and morphine sulfate. A recent review by the American College of Physicians concluded that treating adults with dyspnea with short-term opioids is beneficial, resulting in improvement of refractory dyspnea without significant sedation or respiratory depression.106-111 A suggested starting dose for an opioid naïve patient is 25% to 30% of the dose used for pain with a maximum starting dose of 5 mg orally or if already on an opioid increasing the dose by 30%.

In the child with cancer, dyspnea can be due to airway obstruction from tumor, pleural effusion, pulmonary fibrosis from chemotherapy, superior vena caval syndrome, pulmonary edema, and anemia. Interventions include radiotherapy for tumor-related airway obstruction, thoracentesis for pleural effusion, diuretics to decrease pulmonary edema and transfusion for significant anemia. Treatment decisions are guided by their ability to achieve comfort, and whether the intervention requires hospitalization.

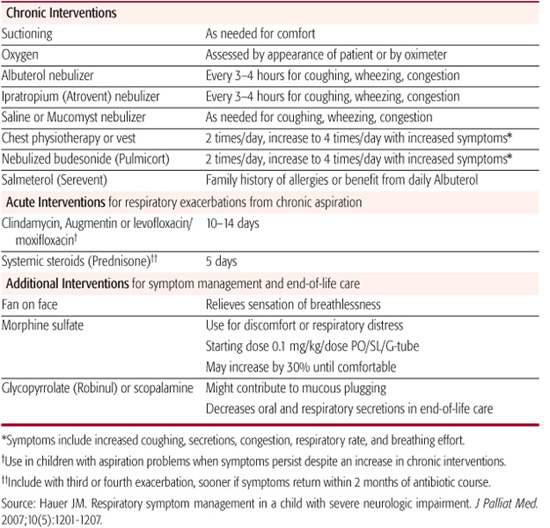

In children with severe neurological impairment recurrent respiratory problems often lead to respiratory failure and mortality.113-116,24,25 As in adults with chronic respiratory disorders, these children require symptom management that incorporates elements used for both chronic and acute respiratory management. Table 126-3 outlines chronic and acute home care strategies, based on experience and evidence, for individuals with severe developmental disability and associated aspiration of oral secretions.117 Note that the table includes consideration of use of morphine sulfate as goals shift from medical treatment to comfort when a decline in health status is observed. Further study is needed to determine when best to integrate morphine sulfate into the care plans of patients who have chronic aspiration and recurrent distressing respiratory exacerbations.

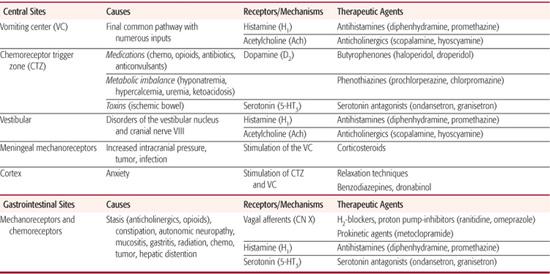

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Nausea, vomiting, and retching are commonly encountered in oncology patients, in children with severe developmental disability, and at the end of life. An understanding of the pathophysiology of nausea and vomiting and the neurotransmitters involved can guide evaluation and selection from the management options available (see Chapter 382). In children with developmental disability retching and vomiting is commonly attributed to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)123 but stimulation of the emetic reflex is likely an underreported source of symptoms in these patients so management options other than treatment of GERD should be considered.124-129

Table 126-3. Respiratory Home Management—Medical Treatment and Comfort Strategies

Symptom management strategies based on involved receptors and origin of symptoms are outlined in Table 126-4. Management of nausea and vomiting includes evaluating for treatable causes in addition to utilizing medications that block involved receptors.

Constipation is a common cause of discomfort and pain at the end of life,61,62 particularly because of opioid use but other causes include decreased mobility and decreased fluid and nutritional intake. In some patients spinal cord compression or bowel obstruction may result from tumor. Bowel obstruction from a tumor may cause refractory vomiting. This can be relieved by placement of a venting gastrostomy tube, or sometmes with use of corticosteroids and octreotide.134-136

Cachexia and Anorexia

Cachexia is a common finding in advanced cancer patients. Poor nutritional intake and increased metabolic demands, impaired taste, and depression may all contribute to weight loss. Treatment should be directed at identifiable causes.137,138

Severe cancer-related wasting is associated with poor outcomes in adult cancer patients139 yet nutrition does not reverse this process.140,141 Physicians can address concerns about starvation by explaining that the cancer itself may be responsible and that increased nutritional intake often cannot halt or reverse this process. Goals for management should instead focus on associated symptoms and maintenance of the child’s level of function.142

When considering enteral or parenteral nutrition it can be helpful to discuss that less benefit may occur along with the potential for complications as the child’s cancer progresses.143 This allows defining a plan to reassess and to discontinue if the patient experiences more harm than benefit. Discussion at the time of institution of supplemental nutrition may make reconsideration of this intervention less distressing for families as the child’s illness progresses.

Pharmacologic interventions include corticosteroids, which can increase appetite and nutritional intake although their effect tends to wane after 4 weeks. Cannabinoids such as dronabinol and megestrol acetate may also increase appetite.144 Megestrol acetate should be used with caution as it is associated with severe adrenal suppression in children with cancer; some have recommended routine steroid replacement for children on megestrol acetate.145

Artificial Nutrition and Hydration (ANH)

Discussing nutrition and hydration can be difficult given the primal need for parents to provide nutrition to their children. Understandably, this makes it difficult for families to consider that artificially provided nutrition may not provide benefit, or may actually cause harm. Discussion should focus on strategies that meet the child’s goals of care.

Certain patients, such as those with brainstem involvement of a central nervous system tumor or with a progressive neurological disease, may develop swallowing impairment, and can be evaluated as discussed in Chapter 31.

For some children, placement and use of a gastrostomy tube may undermine the identified goals of care. When eating provides significant pleasure to the patient, choosing to maintain oral feeding may positively impact quality of life despite known risks. Some may choose to use a gastrostomy tube for most nutrition but to give tastes for pleasure by mouth. As the end-of-life care period nears, nutritional strategies can be reassessed.

Feeding Intolerance

Feeding intolerance can be a source of distressing symptoms for children with severe developmental impairment receiving fluid and nutrition through a feeding tube. As with recurrent respiratory exacerbations as a result of chronic pulmonary aspiration, the initial benefit from treatment interventions may lessen over time. At such times it can be beneficial to integrate medical and symptom management strategies.

Management includes treating contributing problems such as constipation and delayed gastric emptying. Experience shows that some children may benefit from an empiric trial of medications used for nausea and vomiting, being mindful of which medication targets which receptor to avoid duplication. Unfortunately, there is no evidence to guide physicians in such patients; one must be careful not to introduce too many trial options when there is no evidence to support benefit from any one medication. Other intervention strategies include adjustment of feeding schedules, an empiric trial of an elemental formula, an empiric trial of metronidazole for small bowel bacterial overgrowth, and replacing a gastrostomy feeding tube (G tube) with a jejunostomy feeding tube (G-J tube).

Unfortunately, some of these children will have persistent problems despite utilizing these intervention options. At such times, some children will benefit from a decrease by 25% to 30% or greater in the total amount of formula provided by feeding tube. Certain observations may suggest benefit of such a trial: Has feeding intolerance occurred or worsened as there has been a decline in the overall functional status? Is weight gain out of proportion to the linear growth on the same nutrition? Does the child appear puffy or edematous at times? Families again benefit at such times from a reflection on primary goals and determining approaches that meet these goals.

Table 126-4. Treatment of Nausea and Vomiting

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

FATIGUE

FATIGUE

Fatigue is identified by parents as the most common symptom in the last month of life and the source of greatest distress for children with cancer.61,63 Fatigue is also the least likely to be treated.61

Multimodal approaches to treatment may be most effective. Psychostimulants such as methylphenidate can be used to increase wakefulness, particularly when patients have opioid-related somnolence.152 Patients can control the timing of doses, given the short duration of action, to coincide with important events during the day, such as time with family and friends. Other interventions include: treatment of depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, psychosocial interventions, blood transfusions, exercise programs, acupuncture, rest, and relaxation.148,149,153

Psychological Symptoms, Depression, and Anxiety

Children with cancer commonly experience symptoms of depression and anxiety, including the spectrum from “feeling sad and anxious” to meeting diagnostic criteria.61,63,154,155,157-162

It is essential to utilize psychotherapeutic along with psychopharmacologic treatment options. Guided imagery and hypnosis can be effective tools.166 Child life specialists, child psychologists, or other trained experts are essential members of the team to assist children with expressing emotional symptoms of distress through age appropriate activities.

Psychopharmacologic treatment can be considered for symptoms of depression and anxiety that persist despite nonpharmacologic interventions or that meet diagnostic criteria and are of greater severity. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have some safety data in medically ill children, although efficacy has been difficult to demonstrate.167-169

Methylphenidate has been used for the treatment of depression in medically ill adults.170,171 The more rapid onset of effects than occurs with antidepressant agents can be an advantage in the palliative care setting. The disadvantage is the potential to exacerbate anxiety and anorexia.

Benzodiazepines may have some short-term benefit for anxiety symptoms. They should be used cautiously if at all long term given the lack of evidence to indicate long-term benefit and the development of dependence from long-term use.

Delirium and Agitation

Delirium is a disturbance of consciousness with an acute onset over hours to days. Associated features include fluctuating course, disordered thinking, change in cognition, inattention, altered sleep–wake cycle, perceptual disturbances, and psychomotor disturbances.172,173 Symptoms in agitation overlap with anxiety, although these are noted to have more motor than psychological manifestations. Causes include medications (opioids, anticholinergics), metabolic disturbances (infection, dehydration, renal, liver, electrolyte, brain metastases), and psychosocial contributors (pain, emotional distress, vision or hearing impairment).

Management of delirium and agitation first involves evaluating for treatable medical causes, including medications, metabolic disturbances, and sources of discomfort (pain, dyspnea, muscle spasms, position, constipation). It is also helpful to consider conditions that mimic the appearance of agitation, such as akathisia (an unpleasant state of motor restlessness) from antidopaminergic medications, myoclonus or withdrawal from opioids, and paradoxical reactions. Medications that can help manage the symptoms of delirium and agitation include benzodiazepines and neuroleptics.

Sleep Disturbance

Sleep disturbance in children who are seriously ill can include difficulties in falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, early morning awakening, complaints of nonrestorative sleep, and periods of too much sleep.

There are two general approaches for treatment of sleep problems. Pharmacologic treatments include melatonin,183 antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and trazo-done,184-186 clonidine,187 and antipsychotics (especially for patients with delirium).180,188 Benzodiazepines tend to be overused, leading to dependency and tolerance and should only be used in a time-limited manner.189 Psychological and behavioral interventions include stimulus control, sleep restriction, sleep education, and relaxation training.188 When sleep problems are linked to symptoms or correlated with a disorder, treatment of the underlying condition may improve sleep.

Anemia and Bleeding

For a child with fatigue, dyspnea, or significant dizziness, a red blood cell transfusion may add to quality of life.190 As time progresses, the symptomatic benefit from a transfusion may decrease as the disease progresses, offsetting the benefit compared with the risk of transfusion-related complications.

Mucosal bleeding can sometimes be controlled with aminocaproic acid given orally or intravenously to inhibit fibrinolysis.191 Topical options include fibrin sealants.191 The tannins present in black teas can also help to stop bleeding. At home, patients can press a wet tea bag onto bleeding gums. Anticipating the possibility of profuse bleeding can include a plan to have dark sheets and towels readily accessible to mask the color and quantity of blood.

Profuse bleeding in the setting of thrombocytopenia at the end of life can be terrifying if family members are not prepared for this possible event. Most often, platelet transfusions are not possible in the home setting; therefore, careful planning and consideration are necessary so as not to disrupt the child’s last days. Preparing a plan for families can allow them to remain with their child. This can include having dark sheets and towels readily accessible to mask the color and quantity of blood. Management plans for potential distressing symptoms should also be defined, including medication doses for an opioid and benzodiazepine, with medications and syringes readily available. The possibility of intracranial bleeding should also be anticipated and managed symptomatically including a medication plan if a seizure occurs.

Other Symptoms

Fever and infection, seizures, increased intracranial pressure and spinal cord compression all can be disturbing to parents. The desire to treat or investigate is guided by the overall plan of care. Seizures can be managed by rectal diazepam or sublingual/nasal midazolam. Increased intracranial pressure and spinal cord compression due to tumor can be managed with shunting or dexamethasone. Often the shunt becomes obstructed.

MANAGEMENT OF SYMPTOMS AT END OF LIFE

Symptoms that may require management at end of life include pain, respiratory distress, agitation, and secretions. Management of escalating symptoms is outlined in eTable 126.5  . Algorithms or templated orders can improve management of escalating pain, dyspnea or agitation.196 In addition to opioids for pain and dyspnea, adjuncts for agitation and anxiety should include a benzodiazepine (intermittent lorazepam or continuous midazolam) or a neuroleptic (haloperidol).

. Algorithms or templated orders can improve management of escalating pain, dyspnea or agitation.196 In addition to opioids for pain and dyspnea, adjuncts for agitation and anxiety should include a benzodiazepine (intermittent lorazepam or continuous midazolam) or a neuroleptic (haloperidol).

Ketamine has been identified as beneficial as a co-analgesic with opioids for nociceptive pain to reduce the development of opioid tolerance and for neuropathic pain that is poorly responsive to opioids and traditional neuropathic pain medications. Both clinical situations are based on ketamine’s N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist property.197-199 Starting doses used for ketamine were 0.1 mg/kg/hour as a continuous intravenous infusion.

Palliative Sedation

Palliative sedation is the practice of sedating a patient to the point of unconsciousness and is used as a last resort when all other methods of controlling suffering have failed.200,201 Refractory symptoms identified as leading to palliative sedation included agitation, pain, respiratory distress, and myoclonus.202 Though rarely needed, when a child’s refractory symptoms cannot be managed with opioids, benzodiazepines and other adjuncts, palliative sedation may be warranted.200-202 Typically, either benzodiaze-pines or barbiturates are used as sedatives, although propofol has also be useful for this purpose.203,204

A summary of points to consider and to review with family and health care providers include the following:

• The child has a terminal illness and is experiencing an unbearable symptom that is refractory to other interventions.

• Evaluation and management of symptoms has utilized the expertise of palliative care and/or pain specialists.

• Palliative sedation is ethically (including Principle of Double Effect) and legally acceptable and is distinguished from active euthanasia.

• The Principle of Double Effect includes the fact that the intended benefits (comfort) outweigh possible unintended but foreseeable consequences (sedation to unconsciousness and death).

• The decision and principles involved must be discussed with all staff involved.

• After agreement is reached with the child’s health care team, the information is shared with the family with all questions and concerns addressed.

• Consent is obtained and documented.

• Families are prepared that their child may live “hours to days.”

• An appropriate level of nursing care and monitoring is ensured.

• A peaceful, quiet setting, with a minimum of intrusions is created.

• A detailed plan is developed, including drugs, doses, and criteria for increasing medication by boluses or increased hourly infusions.

• The procedure is documented in the medical record.

• Orders not contributing to comfort are discontinued (eg, vital sign monitoring, laboratory studies, certain medications).

• The team should continue to elicit and respond to concerns, questions, and suggestions.

• After the patient’s death, arrange follow-up discussions with the family and with the health care team.

When managing escalating symptoms at end of life, the Principle of Double Effect is often cited.201 This principle includes the following:

• The action must not be immoral in itself.

• The action must be undertaken with the intention of achieving only the good effect. Possible bad effects may be foreseen but must not be intended.

• The action must not achieve the good effect by means of a bad effect.

• The action must be undertaken for a proportionally grave reason (rule of proportionality).

• All medical treatments have both intended benefit and unintended risk, including death.

Examples include: total parenteral nutrition (TPN), chemotherapy, and surgery. When managing escalating symptoms, the interventions are ethical; when the intent is to relieve suffering and not hasten death, death is a possible and not inevitable outcome of the interventions, and there is fully informed consent. When guidelines for symptom management are properly used, concerns about unintended consequences are no greater than normal and concerns about double effect rarely apply to management of escalating symptoms.

Forgoing Artificial Nutrition and Hydration (ANH)

Like other medical interventions, ANH should be evaluated by weighing its benefits and burdens in light of the clinical circumstances and goals of care.209,210 It is permissible to discontinue ANH when it is prolonging or contributing to suffering.

Forgoing artificial nutrition and hydration can lessen discomfort at the end of life as a result of decreased oral and airway secretions with reduced choking and dyspnea. Mouth dryness can be relieved with moistened swabs, ice chips, petroleum jelly on the lips, and careful oral hygiene. Chronically ill individuals often have no hunger when ANH is discontinued and the resulting ketosis produces a sense of well-being, analgesia, and mild euphoria. Carbohydrate intake even in small amounts blocks ketone production with blunting of the positive effects of total caloric deprivation.

Individuals at the end of life without ANH often naturally take in less as physiology, including intestinal function, slows down. Individuals at the end of life with ANH are at risk for vomiting, pulmonary secretions, and edema when the body is no longer able to process the same quantity of nutrition or hydration. It is imperative that we monitor for unintended consequences in individuals with feeding tubes or receiving intravenous hydration and adjust intake accordingly during the end-of-life care period.

When ANH is prolonging or contributing to suffering and is therefore discontinued, it is helpful to estimate for families the length of time that may pass until death occurs, usually 10 to 14 days. This can be shorter when there is a decline in the function of other organs but can be longer when fluids are used to flush a G-tube after medications have been given.

PREPARING FAMILIES FOR END OF LIFE

Issues not related to the management of specific symptoms that are central to providing quality palliative care are discussed in the Chapter 125. These include preparing the family for the end of life, planning the location of death, preparation of home care and/or hospice services, and issues such as autopsy, organ bank donation and any desired tissue banking. In addition, the process of bereavement and care of the medical staff is discussed.

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree