High-Frequency Ventilation

BACKGROUND

Definition

High-frequency ventilation (HFV) is defined by the following:

1. Ventilator rates generally greater than 120 breaths per minute (bpm) or 2 breaths per second (Hz);

2. Tidal volumes (VT) less than dead space.

The use of such small tidal volumes generally requires maintaining higher mean airway pressures (Paw) to avoid atelectasis.

For conventional ventilation,

Minute ventilation ∝ (VT) × (Rate)

However, HFV minute ventilation is more dependent on rate:

Minute ventilation ∝ (VT) × (Rate)2

Types of HFV

High-Frequency Jet Ventilation

High-frequency jet ventilation (HFJV) is a type of HFV that is characterized by the injection of high-velocity gas boluses into the airway over a very short inspiratory time followed by passive expiration. The most common example in US neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) is the Bunnell Jet.

1. The Jet is used in conjunction with a conventional ventilator that requires replacing the endotracheal tube adapter with a special specific adaptor.

2. The conventional ventilator provides positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and allows easy transition between conventional and Jet ventilation.

3. If desired, the conventional ventilator can also provide “sigh” breaths in synchrony with the Jet.

High-Frequency Oscillatory Ventilation

High-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) uses oscillatory movements of a piston in line with the respiratory gas flow, resulting in active movement of air both during inspiration and during the expiratory phase. The most common example in US NICUs is the Sensormedics 3100A.

1. No conventional ventilator is used with the 3100A.

2. A rigid ventilator circuit is needed to avoid volume loss caused by tubing expansion between the baby and the HFOV.

3. The active expiratory phase allows HFOV to run at somewhat higher frequencies than HFJV and smaller VT but makes either gas trapping or atelectasis a concern.

INDICATIONS

High-frequency ventilation was originally developed as a “rescue” treatment of pulmonary air leak situations. Subsequent studies indicated it could be useful for rescue of severe pulmonary hypertension and for patients prior to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Recent trials have demonstrated efficacy for treatment of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). Studies have shown that inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) may be more effective when used in conjunction with HFV.

Improvements in conventional ventilators and their management have tended to obscure the difference between HFV and conventional ventilation. Nevertheless, many centers still resort to HFV when patients:

1. Have persistent hypoventilation despite increased pressures,

2. Have pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) or pneumothoraces while requiring mechanical ventilation at high pressures,

3. Have persistent hypoxemia on high FiO2 despite high Paw, or

4. Are approaching criteria for iNO or ECMO.

TRANSITION TO HFV

Table 87-1 offers values for transitioning to HFV. Baseline preparations include the following:

1. Chest x-rays

a. Determine expansion

b. Check for interstitial emphysema or pneumothorax

2. Arterial blood gases (ABG)

3. Final conventional settings

4. Nurse, respiratory care practitioner, other practitioners are all prepared and present as rapid adjustments may be needed.

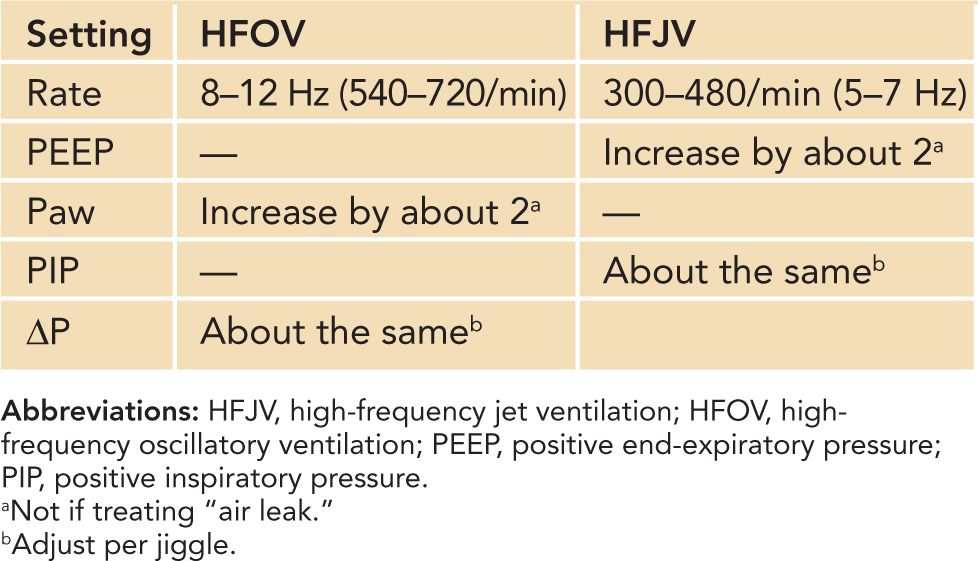

Table 87-1 Transitioning to High-Frequency Ventilation

Make sure the HFV device is calibrated and ready to take over respiratory support before discontinuing conventional ventilation.

1. HFOV: Ensure patient is positioned appropriately for rigid circuit.

2. HFJV: Ensure the heater/humidifier is prepared and the endotracheal tube adapter is ready to be changed.

The following are the starting settings when converting to HFV:

1. PEEP or Paw:

a. The tiny VT used for HFV makes atelectasis a risk.

b. PEEP or Paw is increased 1–2 cm H2O above conventional.

c. Too low a PEEP or Paw increases risk of hyperventilation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree