Gynecologic Pain: Dysmenorrhea, Acute and Chronic Pelvic Pain, Endometriosis, and Premenstrual Syndrome

Marc R. Laufer

A vast array of gynecologic entities and conditions exist that can result in pain for adolescent girls and young women. Pain can be primary (not due to pelvic pathology), secondary (due to pelvic pathology), cyclic, noncyclic, acute, or chronic. Pain is the physiologic response to many pathophysiologic conditions such as distension, stretching, compression, irritation (chemical or infectious), ischemia, neuritis, and necrosis. Pelvic pain can also be referred from another anatomic site. Pelvic pain can arise from numerous causes, including diseases or conditions affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the urinary tract, the reproductive tract, and the musculoskeletal system. Stress and psychosocial issues may increase the intensity of the symptoms and affect the individual’s response to pain and the ability to cope with it. This chapter discusses the approach, diagnosis, and treatment of the adolescent with dysmenorrhea, acute and/or chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, and premenstrual syndrome.

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea, or pain with menses, is very common in adolescents and has been reported in 20% to 90% of adolescent women. The variation in reporting is vast due to how the question is asked and the patient’s family history and frame of reference. Fifteen percent of adolescent women describe their dysmenorrhea as severe. In studies from the 1980s, Klein and Litt (1) found that 59.7% of 2699 girls ages 12 to 17 years reported dysmenorrhea, and of those with dysmenorrhea, 14% frequently missed school because of cramps. In a survey of private school girls (mean age 15.5 ± 1.1 years) done by our faculty in the 1980s, dysmenorrhea was reported as mild by 32%, moderate by 15%, and severe by 6% (2). Many adolescents with dysmenorrhea will not access formal medical care (3). Most dysmenorrhea in adolescents is primary (or functional), but it may also be secondary to endometriosis (see later), obstructing or partially obstructing reproductive tract anomalies (see Chapter 12), or other pelvic pathology.

Typically, the 14- or 15-year-old teenager, 1 to 3 years after menarche, begins to experience crampy lower abdominal pain with each menstrual period. Usually, the pains start within 1 to 4 hours of the onset of the menses and last for 24 to 48 hours. In some cases, the pain may start 1 to 2 days before the menses and continue for 2 to 4 days into the menses. Nausea and/or vomiting, diarrhea, lower backache, thigh pain, headache, fatigue, nervousness, dizziness, or rarely syncope may accompany the cramps.

Etiology

Historically, the etiology of primary dysmenorrhea was poorly understood, and many myths and hypotheses were promoted. Pickles (4) was the first to suggest that dysmenorrhea might be related to a “menstrual stimulant” found in human menstrual fluid that induced smooth muscle contractions. In later studies, he found that the substance was a mixture of prostaglandins F2α (PGF2α) and E2 (PGE2) (5,6). Menstrual fluid prostaglandin levels were several times higher in ovulatory than in anovulatory cycles. Uterine jet washing, endometrial sampling, and collection of menstrual fluid have generally confirmed higher endometrial prostaglandin levels in women with primary dysmenorrhea than in those without symptoms (6,7).

In the uterus, phospholipids from the dead cell membranes are converted to arachidonic acid, which can be metabolized by at least two enzymes: lipoxygenase, which begins the production of leukotrienes, and cyclooxygenase (COX), which leads to cyclic endoperoxides (PGG2 and PGH2). The cyclic endoperoxides are then converted by specific enzymes to prostacyclin, thromboxanes, and the prostaglandins PGD2, PGE2, and PGF2α. Prostaglandin PGF2α mediates pain sensation and stimulates smooth muscle contraction, whereas PGE2 potentiates platelet disaggregation and vasodilatation (8). Exogenously administered PGE2 and PGF2α can produce uterine contractions as well as systemic symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, and dizziness, and are commonly used by obstetricians for the induction of labor. Although plasma levels of prostaglandins are normal in dysmenorrheic women, increased sensitivity or generalized overproduction of prostaglandins may occur. High local levels of estrogen induce transcription of COX-2 synthesis of prostaglandins, which results in expression of aromatase with further increases in estrogen (9).

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (see Table 13-1) have both analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties. The principal action of NSAIDs is inhibition of cyclooxygenase, the enzyme that catalyzes the production of cyclic endoperoxidases from arachidonic acid for the production of prostaglandins. Two isoforms of the COX enzyme have been identified, COX-1 and COX-2. Prostaglandins produced by COX-1 are mainly involved in maintaining the GI mucosal barrier, renal hemodynamics, platelet function, and vascular homeostasis, and also play some role in inflammation (10,11,12,13). The COX-2 enzyme is induced in inflammation, resulting in prostaglandin production (11,12). Nonselective NSAIDs (ibuprofen and naproxen) inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2, whereas selective COX-2 inhibitors (celecoxib, rofecoxib, valdecoxib) exert their actions more specifically on inflammatory processes (13).

Table 13-1 Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The prostaglandin hypothesis has been further strengthened by the observation that drugs that inhibit prostaglandin synthesis can relieve dysmenorrhea and the associated symptoms (8,14,15,16,17,18,19). Several clinical studies have found that NSAIDs are effective in the relief of pain. NSAID agents (see Table 13-1) are divided into different groups: carboxylic acids, propionic acids, acetic acid derivatives, fenamates, enolic acids, napthylkanones, and selective COX-2 inhibitors, each with variability in effectiveness for specific illnesses/processes (8,19,20,21,22).

The carboxylic acid, acetic acid, propionic acid, and fenamate groups are most frequently used in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. The carboxylic acids appear to inhibit cyclooxygenase, but aspirin has little potency compared with some of the other NSAIDs in reducing prostaglandin synthesis, and it may increase menstrual flow (23). Thus, aspirin is used less often in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. Indomethacin is the best-known drug of the acetic acid group for treating dysmenorrhea, but its side effects have prevented its use by most, if not all, patients. Thus, the clinician selects chiefly from the propionic acids and fenamates for clinical treatment of dysmenorrhea.

Ibuprofen and naproxen have been most widely studied for the relief of pain in dysmenorrhea. For example, Chan and associates (15) correlated the relief of dysmenorrhea by ibuprofen with the reduction in menstrual prostaglandin release as measured by a method that can detect menstrual prostaglandin activity in tampon specimens. Total menstrual prostaglandin release per cycle fell from a control level of 59.8 ± 7.2 to 16.8 ± 2.3 (gram PGF2α equivalents) with the use of ibuprofen (15). Numerous clinical studies have found these agents to be effective in both adult and adolescent women, giving pain relief in 67% to 86% of patients. The sodium salt of naproxen has a more rapid absorption than naproxen and can give very rapid relief of symptoms. The prostaglandin inhibitor flurbiprofen also appears to be very effective in the relief of dysmenorrhea (24).

The fenamates are potent inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis and in addition can antagonize the action of already formed prostaglandins (18). This increased activity may give this class of drug a theoretic advantage in treatment. Clinical studies of meclofenamate have shown effectiveness (25,26); this drug also inhibits the activity of 5-lipoxygenase, but the clinical importance of the inhibition of leukotrienes is unknown. These medications are useful when less expensive NSAIDs have not been beneficial.

Combination hormonal therapy (CHT), such as oral estrogen/progestin contraceptive pills, and vaginal ring, has been shown to lessen dysmenorrheal symptoms (27,28). This therapy is effective in part owing to its antiovulatory actions as well as its ability to produce endometrial hypoplasia, less menstrual flow, and subsequently fewer prostaglandins (15,27,28,29).

With the advent of the research on prostaglandins as the cause of dysmenorrhea, the potential influence of psychological issues on dysmenorrhea has received little attention. However, a study of adolescents treated for dysmenorrhea with naproxen sodium found that girls with increased life crisis events experienced greater severity of symptoms in the first month of therapy than did other girls (30). It is possible that prostaglandins may increase in response to physical and psychological stress or that the patient may be more keenly aware of pain when distressed by other problems in her life. As therapy was continued, life stress ceased to have a significant influence on the severity of dysmenorrhea. Those with persistent symptoms, however, did have lower self-concept at follow-up, perhaps because of their initial high expectation of receiving relief.

Patient Assessment

In assessing the adolescent with dysmenorrhea, the physician needs to know her menstrual history and the timing of her cramps, pain, and/or premenstrual symptoms, as well as her response to them. The key questions are these: Is she missing school? If so, how many days? Does she miss other activities? Social events? Does she feel disadvantaged compared to other young women and/or men? Does she have nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or dizziness? What medications has she used to treat the symptoms? What makes the pain better? Worse? What is the nature of the mother–daughter interaction? Does or did her mother or sister have cramps? Is there a family history of endometriosis? Young women whose cramps are disabling out of proportion to the apparent severity may have confounding

factors contributing to their symptoms, such as a reluctance to attend school, a history of physical or sexual abuse, or significant psychosocial problems. The questions about previous medications are particularly crucial, because with the availability of over-the-counter NSAIDs, many adolescents have tried these medications in subtherapeutic doses and have subsequently discarded the concept of their usefulness.

factors contributing to their symptoms, such as a reluctance to attend school, a history of physical or sexual abuse, or significant psychosocial problems. The questions about previous medications are particularly crucial, because with the availability of over-the-counter NSAIDs, many adolescents have tried these medications in subtherapeutic doses and have subsequently discarded the concept of their usefulness.

A physical evaluation should be individualized. A young woman may fear a pelvic examination and thus not speak up about her symptoms. If the pain is cyclic and the young woman is using a tampon without difficulty, then she most likely has a normal vaginal tract and thus may not require further physical assessment. For the virginal adolescent who has mild symptoms, a normal physical examination, including inspection of the genitalia to exclude an abnormality of the hymen, is reassuring. Adolescents with moderate or severe dysmenorrhea who are sexually active should have a speculum and bimanual pelvic examination. In the majority of adolescents who are carefully prepared, a vaginal examination is atraumatic. A rectoabdominal examination with the patient in the lithotomy position is all that is necessary for non–sexually active girls, and this exam will exclude adnexal tenderness and masses. A speculum examination is not necessary if it is not easily tolerated. For the non–sexually active adolescent, a Q-tip can be inserted into the vagina to help determine the presence or absence of a hymenal abnormality and/or a transverse vaginal or longitudinal vaginal septum. The Q-tip is inserted to document the length of the vagina and can be moved from side to side to rule out a fenestrated transverse vaginal septum (see Chapter 12). If the pelvic anatomy needs to be further evaluated and a rectoabdominal examination is noncontributory or not an option, ultrasonography may be necessary. Ultrasonography is useful in defining suspected uterine and vaginal anomalies with obstruction but will not detect abnormalities such as intra-abdominal or pelvic adhesions or endometriosis (see Chapter 23).

Treatment

Treatment includes a careful explanation to the patient of the nature of the problem and a chance for her to ask questions regarding her anatomy. If the results of the examination are normal, treatment should be directed at symptomatic relief. The most common approach is to prescribe one of the NSAID compounds (19) (see Table 13-1).

Most patients can obtain effective relief by starting the antiprostaglandin medicine at the onset of the menses and continuing for the first 1 to 2 days of the cycle, or for the usual duration of cramps. The patient should be told to begin taking the medicine as soon as she knows her menses are coming: “at the first sign of cramps or bleeding.” A loading dose is important in patients with symptoms that are severe and occur rapidly. For such patients, a rapidly absorbed drug such as naproxen sodium would be preferable. Generally, giving the medicine at the onset of the menses prevents the inadvertent administration of the drug to a pregnant woman. However, a patient who is not sexually active and has severe cramps accompanied by early vomiting, and thus is unable to take medication, may often benefit from starting the drug 1 or 2 days before the onset of her menses. A patient may respond to a higher dose or to another NSAID. Since life stresses may lessen the pain relief in the first cycle, the determination of effectiveness in an individual patient should be based on the response in more than one cycle. Usually, medication is prescribed for two to three cycles before it is changed. In addition, a patient may have previously taken inadequate doses of a medicine, particularly ibuprofen, to obtain relief. There is variability in response to NSAIDs, with 70% to 80% of individuals responding to a particular NSAID; lack of response to one NSAID does not preclude a response to another (9,31,32,33,34,35).

The NSAID compounds should be avoided in preoperative patients and patients with known or suspected ulcer disease, GI bleeding, clotting disorders, renal disease, allergies to aspirin or NSAIDs, or aspirin-induced asthma. All of the NSAIDs should be taken with food, even though some patients prefer only liquids on the first day of the cycle. The side effects of these drugs appear minimal in short-term use, but the possibility of allergy and GI irritation and bleeding should be explained to the patient. Some patients complain of fluid retention or fatigue with the use of these agents.

In some patients, NSAID drugs are contraindicated or produce undesirable side effects. In these adolescents, an alternative is tramadol hydrochloride tablets. Tramadol is a centrally acting analgesic that acts by binding to μ-opioid receptors and inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin; it is not a member of either the NSAID or narcotic drug groups. It is indicated for moderate to severe pain. Its efficacy is comparable to that of codeine (30 mg) and oxycodone (5 mg). It is prescribed as 50-mg pills that are taken as 50 to 100 mg every 6 hours; an individual should not take more than eight pills in 24 hours. Caution should be used with this medication if there is a history of seizures. In addition, it should be noted that patients can develop drug dependence with this medication.

In addition to traditional Western medical therapies, patients should be encouraged to exercise, eat a well-balanced diet, and work to reduce stress in their lives. Some girls can continue to exercise or participate in competitive sports during their menses; others may find the discomfort to be too great. Some herbal teas, fruits, and vegetables have been reported to be beneficial to women with dysmenorrhea (36). Magnesium functions in controlling muscle tone and has been studied in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. A decrease in magnesium in women in the luteal phase of the cycle has been demonstrated (37). Some studies have shown a benefit from treating dysmenorrhea with magnesium therapy (see Chapter 31) (38).

The adolescent should be seen initially every 3 or 4 months to evaluate the effectiveness of the therapies. Such visits also facilitate the rapport between health care provider and patient that is essential in the treatment of this problem. Only a few adolescents use their symptoms for secondary gains, such as an excuse to stay out of school or to gain sympathy from their parents. The vast majority of adolescents need to be encouraged to discuss their symptoms and should not be made to feel emotionally unstable because they complain of pain.

If the patient fails to respond to antiprostaglandin drugs and continues to have severe pain or vomiting, or if at the initial evaluation she needs birth control, a course of cyclic CHT (see Chapter 24) should be initiated (see Fig. 13-1). Cramps are usually substantially, if not completely, relieved with the anovulatory cycles and scantier flow. If severe cramps persist despite two to three cycles of ovulation suppression therapy, laparoscopy

is indicated to exclude endometriosis or other organic causes (39,40,41).

is indicated to exclude endometriosis or other organic causes (39,40,41).

If dysmenorrhea is relieved by CHT, medication is usually prescribed for 3 to 6 months and then discontinued (frequently during the summer, when school attendance will not be disrupted). Often, the patient will continue to have relief from cramps for several additional (commonly anovulatory) cycles before the more severe dysmenorrhea recurs. When the cramps recur, a trial of other antiprostaglandin drugs may again be attempted as the sole therapy before CHT is reinstituted. The adolescent with severe dysmenorrhea usually prefers to continue with long-term CHT. The return of increasingly severe dysmenorrhea in spite of continued use of CHT again raises the possibility of organic disease such as endometriosis and calls for a reevaluation and consideration of laparoscopy for definitive diagnosis (see Chronic Pelvic Pain/Persistent Dysmenorrhea below). Symptoms of pain should not be “normalized,” which delays a definitive diagnosis.

Pelvic Pain

Pelvic pain is common in adolescent women and can be characterized as acute or chronic. Pelvic pain can result from gynecologic and nongynecologic etiologies. An extensive listing of nongynecologic and gynecologic causes of acute and chronic pelvic pain is given in Table 13-2 (42,43). Some adolescents may suffer from acute or chronic pelvic pain and not seek attention due to embarrassment or fear.

Acute Pelvic Pain

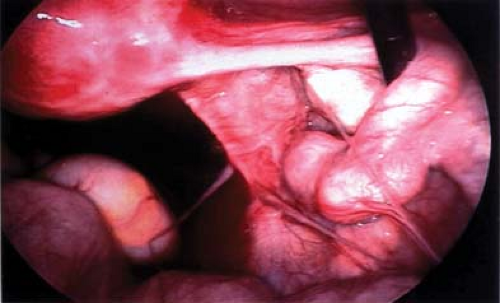

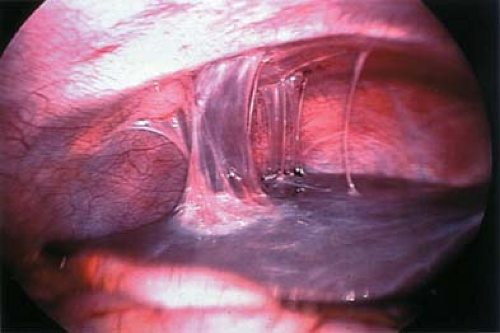

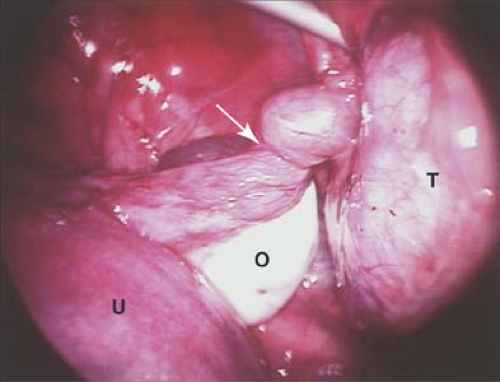

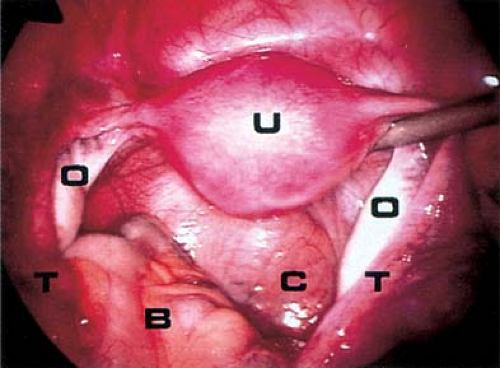

The adolescent girl with acute pelvic pain should receive aggressive evaluation and management, as the differential diagnosis includes life-threatening conditions. The gynecologic causes of acute pain include infections (endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease (see Figs. 13-2 and 13-3), ovarian cysts (see Chapter 21 and Fig. 13-4), endometriosis (see below), ectopic pregnancy (see Chapter 25 and Fig. 13-5), and adnexal torsion (see below). A genital tract obstruction (see Chapter 12) may cause acute symptoms at the time of menarche, although these anomalies can also result in chronic or cyclic pelvic pain. Symptoms associated with infection usually occur over several days. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) (see Chapter 18) is extremely important

to consider in the differential diagnosis of acute pelvic pain in the sexually active adolescent; it has been identified as the most common gynecologic disorder leading to the hospitalization of reproductive-age women in the United States (44,45). PID can result in acute pain or chronic pain from pelvic adhesions (Fig. 13-2) or perihepatic adhesions (Fig. 13-3). The onset of pain associated with adnexal torsion (ovarian [Figs. 13-6, 13-7, and 13-8], tubal [Figs. 13-9 and 13-10], tubal/ovarian [Fig. 13-11], presence of an ovarian cyst with or without rupture [see Chapter 21]) or an ectopic pregnancy (see Chapter 25)

can be abrupt, sharp, and severe. Nausea and/or vomiting may occur with severe pain and is commonly seen with adnexal torsion. However, intermittent or partial adnexal torsion, or an unruptured ectopic pregnancy, may produce crampy pain for several days to weeks prior to an acute episode of complete torsion with infarction of the fallopian tube and/or ovary, or rupture of the ectopic pregnancy.

to consider in the differential diagnosis of acute pelvic pain in the sexually active adolescent; it has been identified as the most common gynecologic disorder leading to the hospitalization of reproductive-age women in the United States (44,45). PID can result in acute pain or chronic pain from pelvic adhesions (Fig. 13-2) or perihepatic adhesions (Fig. 13-3). The onset of pain associated with adnexal torsion (ovarian [Figs. 13-6, 13-7, and 13-8], tubal [Figs. 13-9 and 13-10], tubal/ovarian [Fig. 13-11], presence of an ovarian cyst with or without rupture [see Chapter 21]) or an ectopic pregnancy (see Chapter 25)

can be abrupt, sharp, and severe. Nausea and/or vomiting may occur with severe pain and is commonly seen with adnexal torsion. However, intermittent or partial adnexal torsion, or an unruptured ectopic pregnancy, may produce crampy pain for several days to weeks prior to an acute episode of complete torsion with infarction of the fallopian tube and/or ovary, or rupture of the ectopic pregnancy.

Table 13-2 Differential Diagnosis of Pelvic Pain in Adolescents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In deciding whether the pain is gynecologic in origin, the health care provider must consider GI causes, such as appendicitis, intestinal obstruction or perforation, volvulus, inflammatory bowel disease, infections (e.g., Giardia, Shigella, Salmonella), lactose intolerance, irritable bowel syndrome, or constipation (see Table 13-2). Urinary tract infections and calculi may result in acute pain, and interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome can cause either acute or chronic symptoms (46) (see Chapter 15). Orthopedic causes of pain are frequently forgotten and can be missed initially; the evaluation should include a complete history, an examination of the range of motion of the hips and spine, and tests of the sacroiliac joints.

A complete pain history must include its location, nature, intensity, and radiation; factors that relieve and exacerbate the pain such as walking, exercise, eating, urination, or bowel movements; the date of the last menstrual period; contraceptive and sexual history; associated symptoms such as fever, chills, diarrhea, vomiting, or dysuria; and previous pelvic pain and/or surgery. The psychosocial history should be elicited to assess whether stress, substance use, or sexual abuse might be contributing factors to any case of pelvic pain.

A complete physical examination should be undertaken, special attention being given to palpation of the abdomen, in a search for evidence of masses, tenderness, organomegaly, or peritoneal irritation (peritonitis). Depending on the age of the patient and the size of the hymenal opening, a bimanual vaginal–abdominal, rectoabdominal, or rectovaginal–abdominal examination should be done, if possible, to assess the size of the uterus, the presence or absence of cervical motion tenderness, and/or ovarian/adnexal tenderness. A speculum examination

to assess the vagina and cervix may be done in all sexually active patients and may be considered in virginal patients if the examination can be accomplished without trauma. Tests for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae should be obtained in all patients who have ever had consensual or nonconsensual sexual activity, but these tests can be obtained without the need for a speculum examination with the utilization of vaginal swabs or urine samples for testing (see Chapter 18). Laboratory tests depend on the initial assessment and may include complete blood count (CBC) with differential; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); C-reactive protein (CRP); urinalysis; urine culture; cervical, vaginal, or urinary nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for chlamydia and gonorrhea; sensitive urine or serum pregnancy test; and stool specimen for occult blood. A high leukocyte count (white blood cell [WBC] count) usually indicates infection or inflammation; the WBC count may be slightly elevated or high in cases of ischemia, as may occur secondary to adnexal torsion or bowel obstruction. In acute hemorrhage, the hematocrit may not reflect the extent of blood loss, as there may not have been time for intravascular equilibration to have occurred.

to assess the vagina and cervix may be done in all sexually active patients and may be considered in virginal patients if the examination can be accomplished without trauma. Tests for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae should be obtained in all patients who have ever had consensual or nonconsensual sexual activity, but these tests can be obtained without the need for a speculum examination with the utilization of vaginal swabs or urine samples for testing (see Chapter 18). Laboratory tests depend on the initial assessment and may include complete blood count (CBC) with differential; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); C-reactive protein (CRP); urinalysis; urine culture; cervical, vaginal, or urinary nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for chlamydia and gonorrhea; sensitive urine or serum pregnancy test; and stool specimen for occult blood. A high leukocyte count (white blood cell [WBC] count) usually indicates infection or inflammation; the WBC count may be slightly elevated or high in cases of ischemia, as may occur secondary to adnexal torsion or bowel obstruction. In acute hemorrhage, the hematocrit may not reflect the extent of blood loss, as there may not have been time for intravascular equilibration to have occurred.

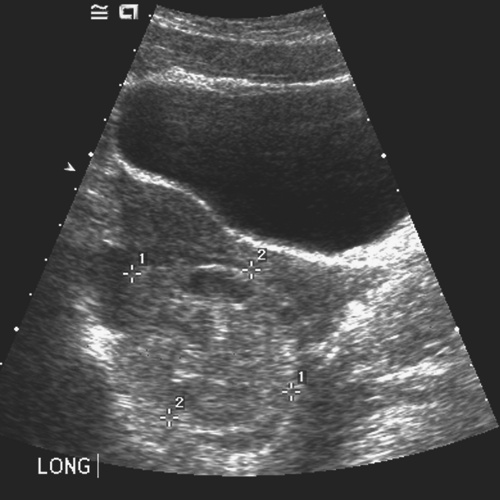

In children or adolescents in whom a pelvic or adnexal mass is palpated or an adequate pelvic examination is not possible, ultrasonography (transabdominal and/or vaginal probe for those who have been sexually active) can be used to aid in the evaluation. It is important to remember that adolescents normally have 1- to 2-cm ovarian follicles, which, though often termed simple cysts on ultrasound evaluation, are normal findings. In addition, children can have numerous small simple ovarian cysts, which usually measure 1 to 5 mm. Endometriosis and PID cannot be excluded by a normal ultrasound. Ultrasound is not ideal for identifying vaginal congenital anomalies (transverse vaginal septum) and thus a single Q-tip insertion and documentation of a normal vaginal length is important to document in addition to the ultrasound. As described in Chapter 12, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and 3-D ultrasonography are the imaging studies of choice for the evaluation of congenital anomalies of the reproductive tract.

Figure 13-12. Laparoscopic view of blood and clot filling the pelvis from a ruptured corpus luteal cyst. |

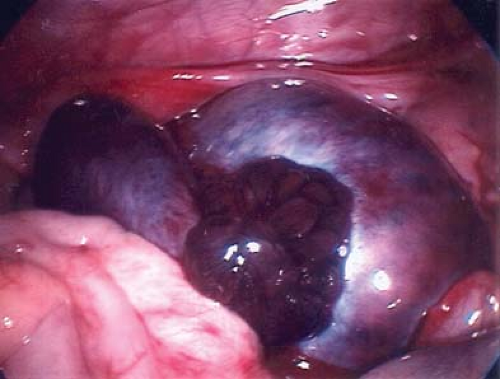

Cul-de-sac free fluid can be present with ruptured simple or hemorrhagic ovarian cysts (see Chapter 21 and Fig. 13-12), leaking or ruptured ectopic pregnancies (see Chapter 25), or endometriosis (see below). The free fluid can be serous clear fluid or blood. The type of free fluid may be determined by the ultrasonic appearance, or it can be definitively determined by culdocentesis. Although rarely utilized any longer, culdocentesis can be performed in an ambulatory setting to aspirate fluid from the posterior cul-de-sac. Cul-de-sac free fluid from a ruptured simple cyst or endometriosis is clear or straw colored, whereas that from a ruptured hemorrhagic cyst or ectopic pregnancy demonstrates free blood. If the blood does not clot, it most likely originates from an intraperitoneal process, whereas if it does clot, it is most likely the result of a misdirected intravascular aspiration. The utility of culdocentesis in the clinical setting of a sensitive and rapid pregnancy test and ultrasound has been questioned (47). At our institution we do not utilize this procedure due to the availability of a sensitive pregnancy test and ultrasound, and also because of the severity of pain during the procedure.

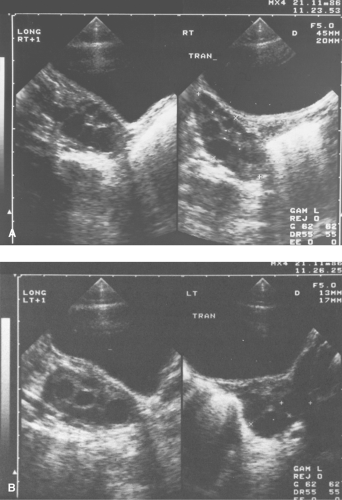

Adnexal (Ovarian and/or Tubal) Torsion

Figure 13-13. “String of pearls” appearance of ovarian follicles with torsion and stromal edema. (Courtesy of Carol Barnewolt, M.D., Children’s Hospital Boston.) |

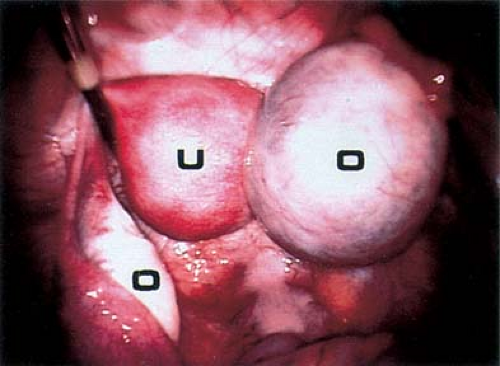

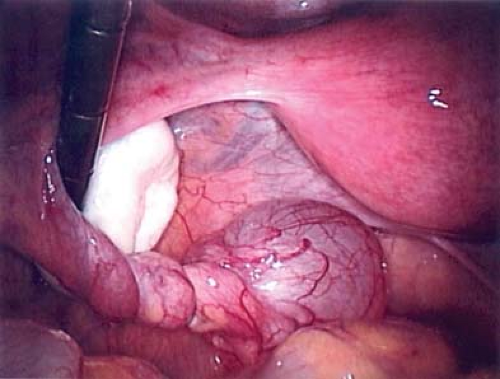

A patient experiencing “waves” of acute pelvic pain with or without nausea and/or vomiting may be experiencing complete, partial, or intermittent torsion of an ovary and/or fallopian tube (Figs. 13-6 to 13-11). Ultrasonography in a case of ovarian torsion may reveal an echogenic mass within the ovary, or an enlarged ovary without a discrete mass with a “string of pearls” appearance of peripheral follicles (Fig. 13-13). A normal ovary can torse in addition to one containing an ovarian/tubal cyst or mass. A ratio of the torsed adnexal volume to the normal adnexal volume >20 is predictive of an ovarian mass within the torsed ovary; conversely, a ratio <20 is predictive of the absence of an ovarian mass (48). The median volume of the torsed ovary was 12 times that of the contralateral normal ovary

in cases of surgically proven torsion (48). Ultrasound Doppler flow studies may be helpful in the assessment of ovarian torsion but are controversial since it is frequently difficult to determine the presence of Doppler flow in normal ovaries and torsed ovaries may still contain Doppler flow if the blood supply has not been completely obstructed by the torsion (48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61) (see also Chapter 23).

in cases of surgically proven torsion (48). Ultrasound Doppler flow studies may be helpful in the assessment of ovarian torsion but are controversial since it is frequently difficult to determine the presence of Doppler flow in normal ovaries and torsed ovaries may still contain Doppler flow if the blood supply has not been completely obstructed by the torsion (48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61) (see also Chapter 23).

Ovarian torsion is more common on the right side and may mimic acute appendicitis, with right lower quadrant pain, vomiting, rebound tenderness, and leukocytosis. For unclear reasons, girls in the 7- to 11-year-old range are especially prone to this problem.

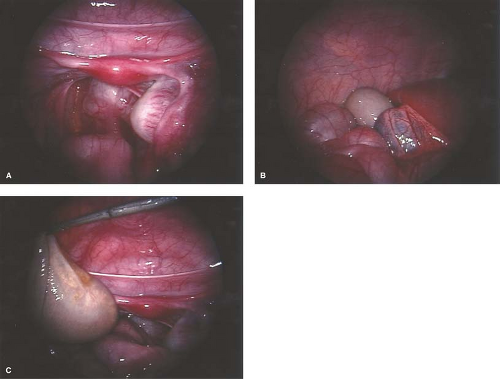

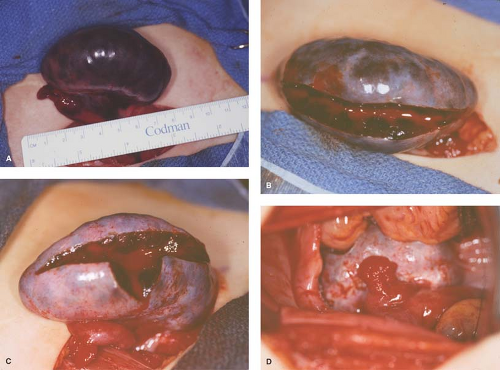

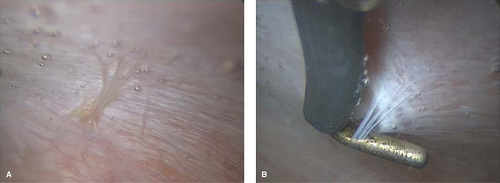

A torsed ovary should be surgically “detorsed” with salvage of the ovary, even if the ovary appears discolored (see Fig. 13-14A) (see Chapter 21). A platelet count may be helpful in cases of an ovarian mass with torsion, as platelet counts may be elevated with malignancy and are readily available in the emergency room setting (62). Since the chance of malignancy is so low and the goal is to save any viable ovary, we have described a bivalve technique that is based on the concept that with torsion there is venous occlusion and thus increased pulse pressure. With the bivalve technique, the ovarian cortex is incised, thus decreasing the pressure within the ovary and permitting arterial blood into the ovary and perfusion of the tissue (63) (see Fig. 13-14B–D). Several weeks to years later, these same individuals may experience torsion of the other adnexa, and if the second torsed ovary is not salvageable the individual is sterile (44,49,50,51,60). Prophylactic oophoropexy (of the contralateral normal ovary) should be considered at the time of the surgery for detorsion of the torsed adnexa. Whether oophoropexy of the contralateral ovary can be helpful in preventing a second asynchronous episode of ovarian torsion of a normal ovary needs evaluation (51). If oophoropexy is elected, it can be safely accomplished by an operative laparoscopic approach (60,64) (see Chapter 21). When evaluating pelvic pain, gastrointestinal and skeletal radiographs and other imaging should be ordered as clinically indicated by the history and physical examination.

Depending on clinical and laboratory assessment, patients with pelvic pain will fall into one of several categories requiring further surgical evaluation, nonsurgical evaluation, or discharge with follow-up (65). Some conditions such as acute hemoperitoneum, ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess, appendicitis, and other GI surgical emergencies require definitive surgery. Some conditions such as gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, and PID require medical management; others (e.g., urinary calculi) require further investigation.

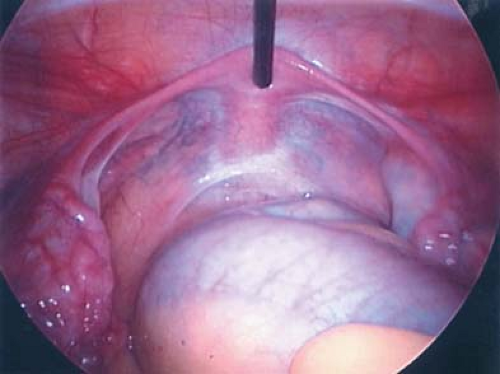

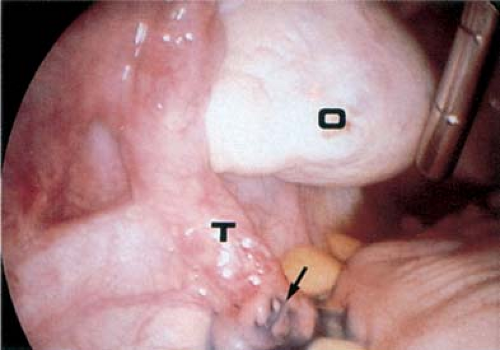

Laparoscopy in Cases of Acute Pelvic Pain

Not infrequently, the diagnosis remains in doubt, and diagnostic and/or operative laparoscopy may be invaluable for a definitive assessment. Laparoscopy is a safe means of evaluating the pelvis in adolescents and young adults and is also used in the management of general surgical, urologic, cardiovascular, and thoracic neurosurgical conditions in infants and children. At the time of laparoscopy, the appendix should be visualized to confirm that it is normal. Laparoscopy has been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of salpingitis (66,67,68,69,70), although its use for this diagnosis is not the current standard of care in the United States because of the risks of general anesthesia. When PID or appendicitis may exist, laparoscopy may help to define the underlying disease process. Microlaparoscopy with the utilization of conscious sedation has been shown to be a feasible option for the evaluation of presumed PID for adolescents in an emergency room setting (70). Visualization of a “normal pelvis” (see Figs. 13-15, 13-16, and 13-17) rules out the need for further surgical intervention and can help direct the subsequent evaluation and therapy. Often, in cases of ruptured ovarian cysts or hemorrhagic corpus luteum, free blood and clots (see Fig. 13-12) can be aspirated and hemostasis ensured by fulguration of areas of bleeding via laparoscopy. Hemoperitoneum is not a contraindication to laparoscopy as long as the patient is not hypotensive. Laparoscopy should be implemented in a standard operating room fashion utilizing a 1.6-, 1.8-, 2-, 3-, 5-, 7-, or 11-mm laparoscope and general anesthesia. Although laparoscopy can be accomplished with local anesthesia, this is not easily tolerated or routine standard of care in the adolescent (70,71,72). Emergent surgery is reserved for cases of adnexal torsion, hemorrhagic ruptured ovarian cysts with hemodynamic compromise, and management of appendicitis.

Figure 13-16. Laparoscopic view of normal pelvis. B, bowel; C, cul-de-sac; O, ovary; T, fallopian tube; U, uterus. |

Acute pain in the adolescent may also occur at menarche if there is an obstructive müllerian anomaly. This can result in hematometra or hematocolpos. The presentation, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of anomalies of the reproductive tract are discussed in Chapter 12.

Mittelschmerz

Mittelschmerz is the term applied to ovulatory pain. The patient typically experiences dull pain at the time of ovulation in one lower quadrant, lasting from a few minutes to 6 to 8 hours. In rare instances, the pain is severe and crampy and persists for 2 to 3 days. The cause of this pain is unknown, but the spillage of normal follicular fluid as the follicle cyst ruptures and expels the oocyte may irritate the peritoneum. It should be noted that ultrasonography studies have detected small quantities of fluid at midcycle in 40% of normal women’s cycles (73), although the presence of free fluid in the posterior cul-de-sac does not indicate a recent ruptured ovarian cyst. Mittelschmerz can be associated with significant bleeding in patients on Coumadin or with Von Willebrand disease.

In most cases, the diagnosis of mittelschmerz is evident from the recurrent nature of the mild discomfort. Documentation of the midcycle occurrence of the pain by menstrual charts is helpful, but many adolescents do not have regular periods and thus the pain may not be able to be documented as “midcycle.” If the patient is being examined for the first episode or for an

exceptionally severe episode, other diagnoses must be excluded, including appendicitis, ovarian torsion, rupture of an ovarian cyst, endometriosis, and ectopic pregnancy.

exceptionally severe episode, other diagnoses must be excluded, including appendicitis, ovarian torsion, rupture of an ovarian cyst, endometriosis, and ectopic pregnancy.

Therapy for mittelschmerz should aim first at a careful explanation to the young woman and her family of the benign nature of the pain and its cause. A heating pad and analgesics such as prostaglandin inhibitors (ibuprofen, naproxen sodium) are helpful. If the pain becomes repetitive in an expected cyclic fashion, CHT can be used to inhibit ovulation.

Chronic Pelvic Pain/Persistent Dysmenorrhea

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is a common and serious health issue for women, and is usually defined in adult women as 3 to 6 months of pain. CPP is estimated to have a prevalence of 3.8% in women aged 15 to 73, which is higher than that of migraines (2.1%), and similar to that of asthma (3.7%) and back pain (4.1%) (74,75). One study found that although CPP occurred in one of seven women in the United States between the ages of 18 and 50, only 49% of those with pain reported that the cause was known (76). For adolescents, CPP can lead to suffering, inability to participate in social interactions, and frequent or prolonged school absence. It is for these reasons that we recommend an evaluation if pain persists for 2 to 3 months, and not waiting 3 to 6 months as in adults.

The diagnosis of CPP in an adolescent is similar to that for acute pelvic pain except that the tempo of the investigation is usually not urgent. An accurate assessment of psychosocial issues and the impact of the pain on the life of the child or adolescent is essential. Chronic pain can be a significant source of frustration for the patient and her parents, and it is not unusual for them to search for multiple opinions from the medical community. Many of these teenagers will have missed many days of school and will be far behind in their schoolwork. If, for example, bowel spasm resulted in the initial symptoms of pain, reluctance to return to school may intensify the pain, causing further absences. Although short-term tutoring may be essential, the clinician should work with the adolescent and her family to encourage her to return to normal social interaction and to school. Granting a request for long-term home tutoring is rarely in her best interests. On the other hand, a definitive diagnosis is extremely important because parents and patients are often concerned that cancer or some other life-threatening condition is present. The girl/young woman’s complaints should be assessed thoroughly so that she feels that her symptoms are taken seriously by the health care provider. A recommendation “to see a counselor” may be interpreted by the adolescent as meaning “the pain is in your head.” In addition, important diagnoses such as PID or endometriosis may be missed unless a complete assessment is undertaken in the patient with persistent pelvic pain. The health care provider needs to reassure the patient that efforts will be made to sort out her problem and that she will not be abandoned even if no diagnosis can be established.

The evaluation of the child or adolescent with CPP requires a history and physical examination similar to that just described for acute pelvic pain. The common problems included in the differential diagnosis are shown in Table 13-2. The history and assessment should take into account the possible gynecologic, GI, urologic, musculoskeletal, and psychosomatic causes. It is helpful to differentiate pelvic pain from nonpelvic abdominal pain (above or below the umbilicus). The patient can be asked to grade the pain on a scale of 1 to 10. This can be helpful in deciding on the long-term management of the chronic pain. A complete history must include questions relating to past or present sexual abuse, as sexual abuse and physical abuse have both been noted to be associated with CPP (77,78,79,80,81). It is important to note the history of abuse, but a history of abuse does not exclude the possibility of an organic etiology for the pain.

The International Pelvic Pain Society (82) has developed an adult pelvic pain questionnaire that can be adapted to an adolescent practice. A complete physical examination including abdominal palpation, musculoskeletal evaluation (including identification of trigger points), assessment for hernias, external genital and reproductive tract assessment, and rectal examination should be performed. It is helpful to ask the patient during the examination to point with one finger to the location of the pain and then to ask her what factors (e.g., exercise, sexual activity, food, urination, bowel movement) relieve or exacerbate the pain. For example, girls with endometriosis may have a constellation of symptoms that include cyclic severe dysmenorrhea, rectal pressure and other bowel problems, and dyspareunia. Activity may increase the symptoms in patients with adhesions and with many of the musculoskeletal problems. Since constipation and other GI disorders (irritable bowel syndrome, lactose intolerance) are such common causes of pelvic discomfort in adolescents, a careful bowel history, dietary history (including information about gum chewing and carbonated beverages), and rectal examination are important. Constipation is very common in the adolescent population due to diet, lack of adequate water and fiber intake, and the lack of time to actually permit regular bowel movements. A trial of stool softeners, high-fiber diet, and increased fluid intake is often essential before other diagnoses are considered.

When considering the next step in the evaluation, a decision point may arise between further exploration with a gastroenterologist or a gynecologist. The symptoms may overlap. Asking the family if there is a history of gynecologic issues such as endometriosis or adenomyosis, infertility, or early hysterectomy among either maternal or paternal relatives may be helpful in directing the young woman toward a gynecologic evaluation prior to a gastrointestinal evaluation.

The practitioner performing the musculoskeletal examination should assess the range of motion of the hips and spine, straight-leg-raising test, symptoms with pelvic compression, and bone tenderness. One study found that “trigger points” were identified in 10.2% of adolescents with chronic pelvic pain and other musculoskeletal etiologies were common (83). Neoplasms of the pelvis and lower spine may be missed on plain radiographs and may require additional imaging for detection. Stress fractures of the pubic ramus and ischium can occur in runners, who may present with hip or groin pain, exacerbated by activity, and bone tenderness.

As noted previously, the pelvic examination should be performed with the patient in the lithotomy position so that the reproductive structures can be adequately assessed. A vaginal assessment is important to identify genital tract obstruction and anomalies. This can be accomplished with a visual inspection and a Q-tip insertion into the vagina to document vaginal tract patency, or with a speculum examination. In addition, samples should be obtained for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae tests, if the patient was ever or is possibly sexually active. The bimanual palpation (rectoabdominal or rectovaginal–abdominal) should attempt to localize tender areas, and the posterior cul-de-sac should be assessed for pain. It is important to remember that

the presence of uterosacral nodularity is found in advanced endometriosis and thus most likely will not be found in an adolescent; a bimanual examination in an adolescent with endometriosis will most likely be normal. With this in mind, it is important to make sure that the perceived need for a pelvic examination should not preclude or be a barrier to the evaluation of the adolescent with persistent dysmenorrhea and possible endometriosis.

the presence of uterosacral nodularity is found in advanced endometriosis and thus most likely will not be found in an adolescent; a bimanual examination in an adolescent with endometriosis will most likely be normal. With this in mind, it is important to make sure that the perceived need for a pelvic examination should not preclude or be a barrier to the evaluation of the adolescent with persistent dysmenorrhea and possible endometriosis.

The laboratory evaluation usually includes a CBC with differential, ESR or CRP, urinalysis and urine culture, urine, vaginal or cervical NAATs for gonorrhea and chlamydia (if ever sexually active), and a sensitive test for pregnancy. As described above, pelvic ultrasonography can be used to assess a mass or a suspected genital tract malformation and to screen patients in whom a satisfactory pelvic examination is not possible. It is advisable to ask the radiologist to screen the kidneys by ultrasound to look for unilateral renal agenesis or other renal anomalies if a genital tract anomaly is suspected.

In our practice, we have evaluated several young adolescents in the earliest stages of pubertal development who have persistent pelvic discomfort and large tender multifollicular ovaries (Fig. 13-18); we have treated them symptomatically with analgesics and low doses of NSAIDs, and the symptoms have resolved with further pubertal development. When prepubertal ovaries are found to be enlarged and multicystic, an evaluation for thyroid disease is indicated (84). In many young girls or adolescents, multicystic ovaries are asymptomatic and are noted when ultrasonography is done for other indications. Operative evaluation should be avoided unless ovarian torsion or tumor is suspected. A full presentation of the diagnosis and management of ovarian masses is presented in Chapter 21. Gastrointestinal series, urologic studies, bone scans, and consultations by specialists should be obtained as needed, not routinely in all adolescents with CPP.

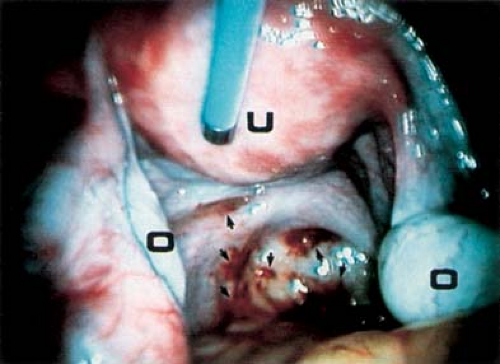

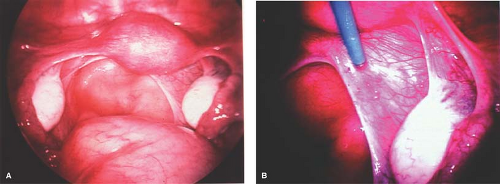

When working with adolescents, the clinician should understand that 3 to 6 months of debilitating pain may interfere with school success and social activities and thus we advocate for an evaluation after 2 to 3 months of symptoms. Adolescents with dysmenorrhea are offered a trial of CHT as noted above. For nonresponsive dysmenorrhea and undiagnosed CPP in adolescents, laparoscopy has become an invaluable aid to diagnosis and therapy (39,40,41,65,83,84,85,86). Laparoscopy allows the physician to make or confirm a specific diagnosis, obtain samples for biopsy, lyse adhesions, and perform operative therapeutic procedures. Before the procedure, the gynecologist should discuss with the patient and her family the possibilities and limitations of operative surgery during the laparoscopy, and determine whether the patient desires a laparotomy in the rare scenario where the procedure cannot safely be performed by laparoscopy. This preoperative counseling can avoid the need for a later second anesthetic for a laparotomy. Negative findings (40,41,42,43) at laparoscopy can be equally valuable in reassuring the patient and her family and in helping her accept the fact that she has a functional problem that is likely to respond to medical and psychological therapy (65,83,84,85). It should be stressed that a gynecologist who is performing a laparoscopy on an adolescent must know what endometriosis looks like in this age group (see Figs. 13-19 to 13-23 and Videos 13-1 to 13-3). If the gynecologist or surgeon is not familiar with lesions of adolescent endometriosis, the diagnosis will be missed.

At our institution, laparoscopy in the evaluation of the adolescent or young adult with CPP is indicated if the patient’s pain is unresponsive to prostaglandin inhibitors and CHT over a 2- to 6-month interval. As previously noted, laparoscopy is useful for the confirmation or exclusion of clinically suspected

endometriosis, chronic PID, ovarian cysts, or pelvic adhesions. Change to a different CHT or waiting longer for relief is usually not productive and only delays the diagnosis and disease-specific therapy.

endometriosis, chronic PID, ovarian cysts, or pelvic adhesions. Change to a different CHT or waiting longer for relief is usually not productive and only delays the diagnosis and disease-specific therapy.

Figure 13-20. A: Normal-appearing pelvis from a distance. B: Clear lesions of endometriosis appreciated with the use of laparoscopic magnification. |

Figure 13-21. A: Clear plaque-like lesion seen under liquid media. B: Same lesion pulled away from sidewall peritoneum. |

Laparoscopy for Chronic Pelvic Pain

At Children’s Hospital Boston, laparoscopy is performed with the patient under general endotracheal anesthesia, in the ambulatory surgery unit. A 5-mm laparoscope is used through an umbilical vertical incision (directly through the base of the umbilicus), and a secondary trocar site is established in the suprapubic area. We do not use a uterine mobilizer/manipulator attached to the cervix, and thus the procedure is performed in the dorsal supine position. A uterine mobilizer/manipulator can be placed in the cervix if a chromopertubation is needed to help define anatomy, but it is usually not necessary in the majority of patients. If a uterine manipulator is used, the patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. A Foley catheter is placed in all patients, as it is unclear how long the surgical procedure will take, and if a catheter is used to empty the bladder and is then removed the bladder may refill to a point of obstructing the surgeon’s view. An oral–gastric tube is helpful in emptying the stomach, and the patient’s respirations are temporarily ceased during the moments of insertion of the insufflation needle and trocar. We prefer to utilize the radially expanding trocar dilation technique as there is no cutting of the fascia with this method and thus decreased risk of postoperative hernias (87). In addition, the surgeon should be aware of adolescent-specific issues that increase the risks of laparoscopy such as low or very high BMI (increased risk of injury with the insufflation needle insertion) (88).

A thorough systematic evaluation of the peritoneal cavity should be undertaken at the time of laparoscopy. The surgeon should avoid going directly to evaluate only the pathology; a systematic approach for complete evaluation of all structures should be undertaken to assure that nothing is missed. We begin with an evaluation of the peritoneal contents directly below the umbilical port to ensure against an iatrogenic injury. Next the patient is placed in steep Trendelenburg position and the bowel is pushed over the pelvic brim. The inguinal regions are then evaluated to see if there is a patent processus vaginalis (see Fig. 13-24) or inguinal hernia. Next the anterior cul-de-sac is evaluated and then the laparoscope is directed to the right ureter. The ureter is identified at the level of the pelvic brim and followed down to the uterine vessels. The right tube and ovary are then evaluated and the ovary is lifted so that the ovarian fossa can be evaluated. The uterus and posterior cul-de-sac are then evaluated. The left pelvic brim is then identified and the ureter and its path visualized. The left tube and ovary and the left ovarian fossa are explored. Once the pelvis is evaluated, the upper abdomen is explored. The appendix, liver, gallbladder, stomach, and intestines are inspected. The diaphragm and anterior abdominal wall are also evaluated.

Figure 13-24. Laparoscopic view of an enlarged left inguinal ring with round ligament entering ring (patent processus vaginalis), a potential hernia site. |

The most likely diagnosis is that of endometriosis (see below), but other findings include PID (see Chapter 18), ovarian cysts (see Chapter 21), genital tract malformations with obstruction (see Chapter 12), and cases of ileitis, infarcted hydatid of Morgagni, inguinal defects, and adhesions. More experienced surgeons will have a higher rate of identification of endometriosis, especially in adolescents. No apparent gynecologic cause of the chronic pain is rarely encountered. At other centers, a larger percentage of normal laparoscopic examination results have been reported. The much higher number of patients with early endometriosis in the Children’s Hospital Boston series reflects the difficulty of identifying very early endometriosis (see Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Endometriosis below), thus underscoring the need for a gynecologic surgeon familiar with the appearance of adolescent endometriosis. In a study at Children’s Hospital Boston, adolescent women aged 13 to 21 were evaluated when their pelvic pain had lasted longer than 3 months and had not responded to NSAIDs and CHT (39). Approximately 70% had endometriosis; the laparoscopic findings are shown in Table 13-3. It should be noted that the data from this study were collected prior to the utilization of

high-definition camera equipment and thus are probably an underestimate of the current rate of identification of endometriosis. The presenting symptoms of the patients with and without endometriosis are shown in Table 13-4. A study by John Rock and colleagues showed a similar rate of endometriosis in their adolescent patient population with chronic pelvic pain (89).

high-definition camera equipment and thus are probably an underestimate of the current rate of identification of endometriosis. The presenting symptoms of the patients with and without endometriosis are shown in Table 13-4. A study by John Rock and colleagues showed a similar rate of endometriosis in their adolescent patient population with chronic pelvic pain (89).

Table 13-3 Laparoscopic Findings in Adolescent Patients with Chronic Pelvic Pain not Responding to Oral Contraceptives and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 13-4 Characteristics of Subjects with and Without Endometriosis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

An association between CPP and bowel-to-pelvic sidewall adhesions (Fig. 13-25) has been debated, as this finding could represent adhesions or normal peritoneal reflection. The cause of adhesions is unknown, but they are believed to be the result of infection, previous surgery, or endometriosis. In women with CPP, a recent study found a higher rate of colon-to-sidewall adhesions than in controls (93.3% vs. 13.3%) (90). The authors also found that adhesions may occur with or without the presence of endometriosis, but that those patients with CPP had a higher rate of endometriosis than controls (46.7% vs. 6.7%). Others have suggested that a causal relationship between adhesions and pelvic pain is unproved (91). At our institution, when bowel adhesions are identified in adolescents with CPP, a laparoscopic lysis of adhesions is undertaken, and then a random posterior cul-de-sac biopsy specimen is obtained for microscopic evaluation to rule out microscopic endometriosis (see below). Our studies have shown a correlation of adhesions with endometriosis in patients with pelvic pain; as shown in Table 13-3, no cases of adhesions were identified in patients without a history of previous surgery or the existence of endometriosis (39). Patients who have undergone prior surgery may have adhesions as a result, or may have a herniation of bowel or omentum at the site of a previous laparoscopy incision.

Figure 13-25. Bowel adhesions (arrows) to sidewall. B, bowel; LO, left ovary; RO, right ovary; U, uterus. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree