Gynecologic Issues in Young Women with Chronic Disease

S. Jean Emans

Marc R. Laufer

Tremendous medical advances have improved the quality of life of patients with chronic disease as well as their life expectancies. This chapter focuses on gynecologic health issues specific for these young women, including pubertal development, menstrual function, fertility, and pregnancy. Contraception is discussed separately in Chapter 24, approach to girls with developmental delay in Chapter 28, and special reproductive health issues of cancer survivors in Chapter 29. With rapid changes in the field of genetics and obstetric management, clinicians are encouraged to counsel their patients on available reproductive options in advance of conception so the risk and benefits can be discussed with the appropriate maternal–fetal medicine and genetic experts. A list of conditions that may benefit from induction of amenorrhea are provided in Table 27-1 and therapeutic options for the induction of amenorrhea are presented in Table 27-2.

Asthma

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases. By age 18, one in five Americans is diagnosed with asthma (1,2). Asthma is seen three to four times more commonly in boys than in girls prior to puberty, and by age 10 the ratio begins to change such that after puberty asthma is more common in girls and remains so throughout adulthood (1,2,3). The rise of asthma at the time of puberty has been noted to correspond with the change in sex steroids (4,5). Girls with asthma may be more likely to have earlier menarche (6), and irregular menstrual cycles were more common in girls with asthma than controls (7).

Up to 40% of women with asthma report an increase in symptoms and a decrease in 1-second forced expiratory volume (FEV1) during the premenstrual period (3,8). Women with moderate to severe asthma have three to five times more exacerbations premenstrually when compared to women with mild disease (9,10,11). The exact etiology of these menstrual related changes has not been determined. Studies have suggested efficacy of a variety of drugs for suppression of cyclic or hormonally induced symptoms such as: leukotriene receptor antagonists (12), long-acting β2 agonists, progesterone, estradiol, continuous oral contraceptives, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs with add-back therapy (8), but further studies are needed (see Tables 27-1 and 27-2). Optimization of asthma therapies using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines (www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma) prior to the onset of the regular cyclic exacerbations is an important first step.

Asthma and Pregnancy

Women with asthma have fertility rates that do not differ from the general population (13); however, they are at risk for adverse maternal outcomes and close surveillance is essential (14). Pregnancy is not associated with an increase in new-onset asthma, but approximately 5% of those with preexisting asthma will develop problems during pregnancy (3,4). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology have a guideline for asthma management and medications during pregnancy (15). During pregnancy, budesonide is the preferred inhaled corticosteroid and albuterol should continue to be used as a rescue medication.

Cystic Fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is the most common autosomal recessive life-threatening disease among whites and occurs in 1 in 2500 live births. In the past 40 years, the life expectancy of persons with cystic fibrosis (CF) has greatly increased. According to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (www.cff.org), median survival was 10.6 years in 1966, 20 years in 1981, 29.4 years in 1992, 33.4 years in 2001, and 37.4 years in 2008 with more than 45% of people with CF 18 years or older.

Pubertal Development and Menstrual Function

Adolescent girls with CF may have low weight for height and chronic pulmonary infections that delay pubertal development and menarche (16,17,18). In a study in the early 1980s, the mean age of menarche was 14.4 years versus 12.9 years for controls (16). A decade later, a study of Swedish girls with CF found even with improved nutritional and clinical status that the mean age of peak height velocity was 12.9 ± 0.8 years and the mean age of menarche was 14.9 ± 1.4 years (17). Patients who were homozygous for ΔF508 and those with abnormal oral glucose tolerance tests were significantly older at menarche (15.2 ± 1.9 years) compared to those who were not (14.7 ± 0.9 years) (15). Multicystic ovaries, an increased luteinizing hormone–to–follicle-stimulating hormone (LH/FSH) ratio, and decreased sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) without hirsutism have been reported in young women with CF, 50% of whom had diabetes mellitus (19).

Reproductive Issues

Sexuality counseling of adolescent girls is a critical part of their care, which is often neglected (20,21,22,23). Young women with CF generally initiate sexual activity at the same age as other healthy young women but may be less likely to use contraception than control subjects (20). Pregnancies in women with CF are frequently unplanned, as some women may assume that they are infertile. Because adolescent and young adult patients with CF often think of their pulmonologist as their “main doctor,”

they may not receive adequate clinical preventive services and counseling about sexuality (23). Patients with CF have indicated a desire to spend time alone with their “main doctor” between 13 and 16 years of age and wanted their health care providers to discuss risk behaviors, school, work, and finances with them (23).

they may not receive adequate clinical preventive services and counseling about sexuality (23). Patients with CF have indicated a desire to spend time alone with their “main doctor” between 13 and 16 years of age and wanted their health care providers to discuss risk behaviors, school, work, and finances with them (23).

Table 27-1 Conditions that May Benefit from the Therapeutic Induction of Amenorrhea | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Although chronic illness and poor nutritional state may lower the fertility of an individual woman with CF (24,25), some have postulated that the thick cervical mucus (lower water content) may also be a barrier to sperm (26). A woman with CF has approximately a 1 in 40 chance of having an affected offspring if the carrier status of the father is unknown, and a 50% chance if the father is a heterozygote. Combining in vitro fertilization and preimplantation diagnostic testing for CF has resulted in normal offspring (27).

Successful pregnancies have been reported in women with CF (25,28,29,30,31). These studies confirm that pregnancy is well tolerated by women with mild disease with near-normal lung function (32), but that both maternal and fetal outcomes are more guarded for those with moderate to severe disease. Pregnancy should be avoided if pulmonary hypertension or cor pulmonale is present (33). Careful medical assessment of the cardiac, pulmonary, and nutritional status is important before patients undertake a planned pregnancy.

Table 27-2 Medications Used to Induce Therapeutic Amenorrhea | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Other Issues

A pseudopolypoid cervical ectropion has been noted in CF patients, in both users and nonusers of oral contraceptives (OCs) (34,35). There is also increased production of cervical and vaginal mucus, which can cause a bothersome discharge. There is no treatment for this condition and health care providers should avoid destructive (cryotherapy or laser therapy) or surgical procedures to the cervical ectropion as these interventions could result in cervical stenosis and infertility.

Gastrointestinal Disease

Pubertal Development and Menstrual Function in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

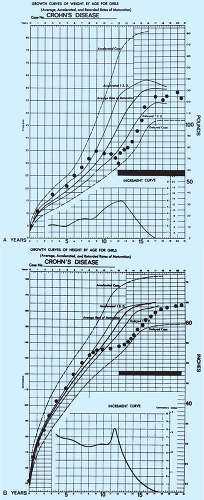

Adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may experience growth failure and delay of puberty and menarche. Delayed growth may be the first sign of IBD, especially in Crohn disease (Fig. 27-1), and may overshadow symptoms of the gastrointestinal dysfunction (36,37,38). In girls with IBD, gonadotropin and estrogen levels are low, implying a depressed hypothalamic–pituitary axis. Nutritional and medical therapies such as enteral nutrition, steroids, immunosuppressive agents, and sometimes surgery (localized resection) to treat active bowel disease are important to ensure normal pubertal growth and development, regular menses, quality of life, and emotional maturation (36,38,39). Although excess corticosteroids typically impair growth, when Crohn disease is adequately treated with steroids or preferably immunosuppressive agents, the patient often has a growth spurt.

Reproductive Issues in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Studies have been conflicting on the fertility of women with IBD in part because these reports may not adjust for factors such as smoking, age, whether the patient was attempting to conceive, or whether she had concerns about heritability, risk of congenital abnormalities, or teratogenicity from medications (37,40,41). Although many women with IBD reported fear of infertility, they were not more likely to visit a fertility specialist to get their questions answered than were normal women (41). Among patients with ulcerative colitis, 90% of patients with this disorder will be able to conceive if pregnancy is desired (40,42,43), but pregnancy rates (without interventions) are significantly lower and C-section rates higher for those treated with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis than controls (44,45). Similarly, fertility in women with Crohn disease may be affected by factors such as lack of a desire for intercourse, pain, fear of infertility, occlusion of fallopian tubes, and perineal fistulas (41,46,47).

The common medications used to treat IBD, azathioprine and corticosteroids, are usually well tolerated in pregnancy (43,47,48), but the risks and benefits require individual counseling of each patient. Most specialists feel that active disease is more deleterious to the pregnancy than maintaining medical

therapy and thus the medications are continued during pregnancy and breastfeeding (49).

therapy and thus the medications are continued during pregnancy and breastfeeding (49).

The majority of women with either ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease complete normal full-term pregnancies with healthy offspring. However, there is an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, prematurity, and low-birth-weight babies, especially if the disease is active (47,50,51). For example, 90% of women with inactive ulcerative colitis completed a full-term pregnancy (52). Successful pregnancy outcome in women with Crohn disease also reflects the predominance of women with inactive disease in these studies (40,53). It has been estimated that 15% to 40% of patients with Crohn disease will have an exacerbation during their pregnancy and about an equal number will remain unchanged or improved (54). The absence of gastrointestinal problems in a pregnancy does not predict the course of IBD in future pregnancies. Postpartum, the patients usually return to their prepregnancy gastrointestinal disease state.

Other Issues

In Crohn disease, ulcers of the perineum may mimic herpetic lesions but in fact are granulomatous lesions (see also Chapters 4, 5 and 17 and Fig. 5-57 and Fig. 17-11). These ulcers as well as labial swelling, which may be bilateral or unilateral, may be the first sign of Crohn disease, and can occur in children and adolescents. The initial symptom may be vulvar pain (55,56,57). The ulcers may last for weeks to months and can progress to fistula tracts that may require long-term antibiotic therapy (e.g., metronidazole) or even surgery (58).

The recommendations for contraceptive methods and IBD are discussed in Chapter 24 and vary with the extent of disease. Most but not all studies suggest that patients with IBD are at increased risk of thrombosis, especially those who are older, have active disease, and have more extensive disease. Prolonged immobilization, fluid depletion, surgery, and inflammation may all play a role; studies are needed to ascertain whether OCs further increase the thrombosis risk in these women (51). OC use does not appear to be associated with relapse (51).

The newest Papanicolaou (Pap) test recommendations suggest initiating screening at the time of sexual activity in immunosuppressed teens; however, studies are conflicting (59,60,61). Several studies have not found an increased risk of abnormal Pap tests in young women with IBD. Clinicians should discuss the options with their patients.

Celiac disease has been associated with delayed puberty and amenorrhea as well as low bone mass in adolescents, and appropriate laboratory studies (antitissue transglutaminase antibodies and immunoglobulin A [IgA] level) should be obtained in the workup of these problems (see Chapters 8 and 9).

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) (gastrointestinal polyposis and oral cutaneous pigmentation) is an autosomal dominant condition with the majority of patients having a causative mutation in the STK11 gene, which is located at 19p13.3 (62). The cancer risks include breast, gastrointestinal, and ovarian. In addition, PJS has been associated with adenocarcinoma of the cervix (63,64). Patients as young as 2 years old with PJS have also been found to have ovarian tumors (see Chapter 21), including granulosa cell tumors, cystadenomas, mucinous adenocarcinomas, Brenner tumors, dysgerminomas, sex cord tumors with annular tubules (SCTAT), and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors (65,66,67,68,69). The associated cervical neoplasia is a specific type of adenocarcinoma termed adenoma malignum. Breast carcinoma has also been reported. There are currently no accepted screening recommendations for girls with PJS, whereas for boys annual testicular examinations with ultrasound of any abnormality is recommended starting from birth to age 12 (62). Ultrasound can be obtained to screen for ovarian tumors in girls, and regular yearly gynecologic examinations are essential in this at-risk adolescent/young adult population.

Liver Disease

Pubertal Development and Menstrual Dysfunction

Women with chronic liver disease may have irregular menses, particularly amenorrhea that resolves if the liver disease improves. Amenorrhea has also been noted to resolve when spironolactone, an androgen inhibitor, was discontinued (70). Women with severe liver disease may also present with severe menorrhagia due to thrombocytopenia and the decreased production of clotting factors. Treatment of menorrhagia should be directed at treating the underlying disease and replacing clotting factors. Patients with this condition may not do well with oral estrogen therapy, as their liver dysfunction precludes adequate metabolism. Hormonal therapies include norethindrone acetate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, GnRH analogs, combination hormonal contraceptive, and transdermal estradiol (see Chapter 10) with an added oral progestin (71). For example,

cholestasis has been reported in a patient with a liver transplant who was taking a 50-μg ethinyl estradiol combined OC (72). Transdermal estradiol has the advantage of avoiding the liver “first-pass” effect. In the rare occasion hormonal manipulation fails, a dilatation and curettage with adequate preoperative coagulation factor replacement may be necessary. Chronic liver disease is associated with anovulation, amenorrhea, and de-creased fertility.

cholestasis has been reported in a patient with a liver transplant who was taking a 50-μg ethinyl estradiol combined OC (72). Transdermal estradiol has the advantage of avoiding the liver “first-pass” effect. In the rare occasion hormonal manipulation fails, a dilatation and curettage with adequate preoperative coagulation factor replacement may be necessary. Chronic liver disease is associated with anovulation, amenorrhea, and de-creased fertility.

Sickle Cell Disease

Pubertal Development and Menstrual Function

Individuals with sickle cell disease and thalassemia can have endocrine complications affecting growth, sexual development, fertility, bone mineral density, diabetes, hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, and hypoadrenalism (73

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree