19.1 Growth and variations of growth

Genetic factors

The genetic background of individuals is the major determinant of growth potential: tall parents generally have tall children, whereas short parents have short children. Although children’s heights at maturity resemble those of their parents, little is known about the exact location of the individual height controlling genes, how many genes are involved or how they direct cellular growth. Major genetic disturbances such as chromosomal abnormalities are often reflected in poor growth patterns. For example, with loss of a sex chromosome in 45,XO Turner syndrome, as shown in Figure 19.1.1 (see also Chapter 10.3), adult stature is severely compromised. Other less severe chromosomal abnormalities also may result in abnormalities in stature.

Many inherited genetic conditions can also result in growth disturbance. The most striking of these are the skeletal dysplasias, which often follow an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance. The classical example of a skeletal dysplasia is achondroplasia, described in Chapter 10.3. Chromosomes may also influence tall stature, as seen in the case of an individual with an extra sex chromosome, for example Klinefelter syndrome XXY, which frequently leads to an adult height above that anticipated from the family pattern.

Hormonal factors

Those of significance in growth are:

Thyroid hormone

Thyroxine is very important for postnatal growth. Children with untreated hypothyroidism may show both intellectual impairment and profound growth retardation, with delayed bony maturation (see Chapter 19.2).

Phases of growth

There are three main phases of growth: fetal growth, childhood growth and the pubertal growth spurt.

Pubertal growth spurt

Puberty

• The earliest sign of puberty in females is breast budding, at an average age of 10–11 years.

• The earliest sign of puberty in males is testicular enlargement, at an average age of 11 years.

• Pubic and axillary hair development usually follow the onset of breast development in girls and of testicular enlargement and genital development in boys.

• The pubertal growth spurt occurs at an average age of 11.5 years in females and 13.5 years in males.

• The growth spurt in puberty is the most rapid phase of postnatal growth.

Assessment of growth

Percentile charts

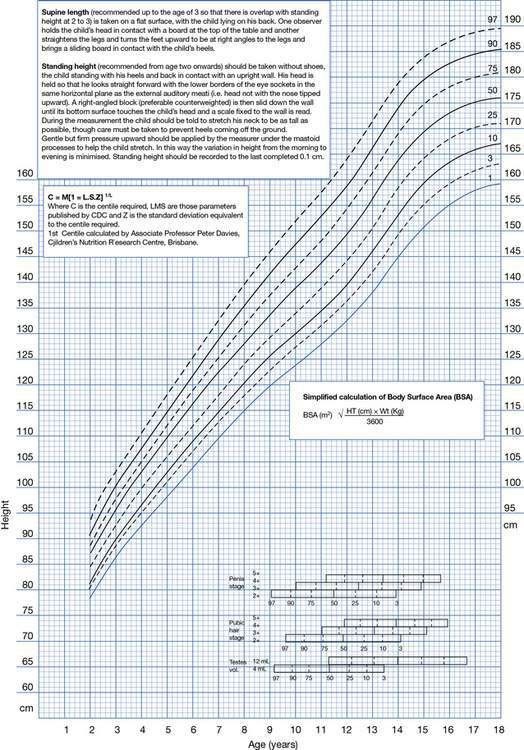

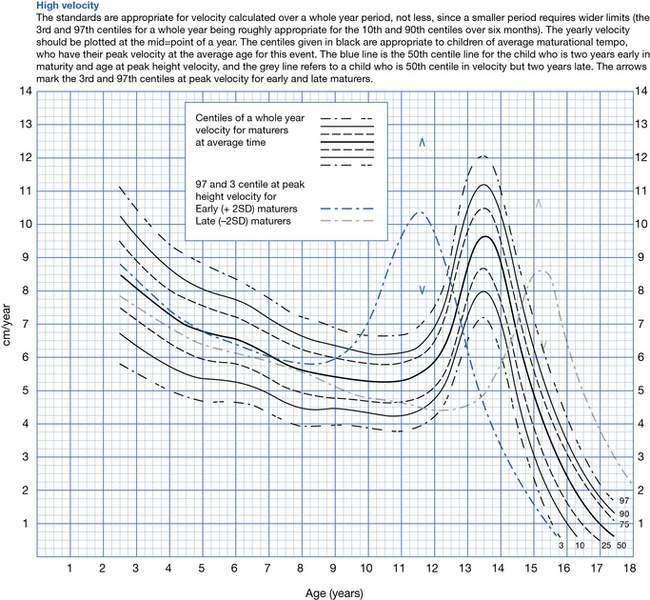

Any health professional who deals with children must have a working knowledge of normal variations in growth and development, and must be able to use a percentile chart. Childhood and pubertal growth patterns can be appreciated by examining growth charts, including linear height and weight charts (Fig. 19.1.2) as well as height velocity charts, indicating annual rate of growth (Fig. 19.1.3).

Fig. 19.1.2 Male height centile chart. A similar chart is available for females. CDC, Centers for Disease Control.

(Reproduced with permission from Pfizer.)

Fig. 19.1.3 Male height velocity chart. A similar chart is available for females.

(Reproduced with permission from Pfizer.)

These charts demonstrate the range of normal growth, expressed either as percentiles or as standard deviations (sd) from the mean for age. The percentile curves are derived from the normal distribution (bell-shaped curve) of the data. The median is the 50th percentile and indicates that 50% of the measurements of a normal group of children are above and 50% are below that point. The 50th centile ‘final’ height value for males is 176 cm and for females is 163 cm. Children whose height or weight are 2 sd above or below the mean fall approximately between the 3 rd and 97th percentiles (Fig. 19.1.2). There will be three normal children in every 100 who will be at or below the 3 rd centile and three in every 100 who will be at or above the 97th centile.

Assessment of growth velocity (Fig. 19.1.3) is of far greater clinical significance than single measurements of height, and should be based on sequential measurements taken at 3-monthly intervals during a period of 6–12 months. When measured over this time period, a normal child will tend to follow the same height percentile (Fig. 19.1.2). A child with an organic or endocrine disease will tend to deviate from the percentile and may move across percentile lines. Thus serial measurement of children is the key to the assessment of their growth status.

Short stature

The management of a child with short stature requires consideration of a number of issues. It is important to realize that the majority of short children will have no pathology but will either be following a familial pattern or have a variant of normal growth. The main causes of short stature in order of frequency of diagnosis are summarized in Box 19.1.1. As can be seen, endocrine causes of short stature are the least common.

Variations from normal

Familial (genetic) short stature

Important features of familial short stature are as follows:

• Height will track parallel to and below the 3rd centile.

• The growth rate (growth velocity) is usually normal.

• The adult height percentiles of both parents should be plotted on the child’s growth chart to assess whether the child’s height is appropriate for the heights of the parents.

• Pubertal development usually occurs at the appropriate time.

• Markers of physical maturation such as bone age tend to be consistent with chronological age.

Constitutional delay in growth and puberty

• affects boys more commonly than girls, and boys are more likely to present to medical attention

• often there is a family history of a parent being short as a child, with delayed puberty and eventual catch-up with peers

• these children are the so-called ‘slow growers and late bloomers’

• markers of physical maturation such as bone age are delayed

• the delay in puberty and associated delay in fusion of bony epiphyses means that both the pubertal growth spurt and the completion of growth will be delayed

• these children (most often boys) tend to grow into their late teenage years or early twenties.

Pathological causes

Small for gestational age

Babies may be born small for gestational age (SGA) as a result of a number of fetal, maternal and environmental factors (see Chapter 11.2). Some SGA children fail to demonstrate catch-up growth in the first 2 years of life and remain small.

Chronic disease

Chronic disease is a major cause of growth failure:

• Usually the growth failure is associated with a similar fall off in weight velocity.

• An endocrine problem is unlikely to be the cause of poor growth if both the weight and height are affected.

• Nutritional insufficiency may contribute to the growth failure of chronic disease as a result of inadequate or inappropriate intake, poor absorption or impaired or excessive tissue utilization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree