Group B Streptococcus Infections

Morven S. Edwards

Group B streptococci has been a common cause of invasive infection in neonates and young infants for several decades.1 In recent years, it has been understood that group B streptococci also is an important cause of maternal obstetrical morbidity and of fetal loss. Within the past decade, a significant decline in the incidence of early-onset group B streptococcal neonatal infections has been observed in association with universal culture-based screening of pregnant women and administration of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis to women colonized with group B streptococci.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Rates of maternal rectal and vaginal colonization with group B streptococci during pregnancy range from 20% to 30%. Without interruption of transmission, approximately 50% of infants delivered of a colonized mother acquire mucous membrane colonization. The risk for invasive infection among colonized infants is approximately 1%. This risk is increased when there is premature onset of labor, maternal chorioamnionitis, a prolonged interval between rupture of membranes and delivery, twin pregnancy, or maternal postpartum bacteremia, among other factors. Heavy maternal colonization also increases the risk for neonatal infection. Fetal aspiration of infected amniotic fluid can result in the development of congenital pneumonia with symptoms at or shortly after birth.

Group B streptococci are gram-positive cocci that grow readily as white to gray white colony-forming units with a narrow zone of β-hemolysis when inoculated on blood agar. Group B streptococci have been classified, based on capsular polysaccharide antigens, into 8 types. Contemporary data indicate that types Ia, III, and V predominate in early-onset disease, accounting for more than three quarters of isolates from infants with invasive infection.2,3 Together with types Ib and II, these 5 types account for 99% of isolates from infant invasive early-onset disease. Among late-onset cases of group B streptococcal infection, type III strains predominate, accounting for approximately two thirds of infections. Serotype III strains also account for approximately 90% of isolates from infants with meningitis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

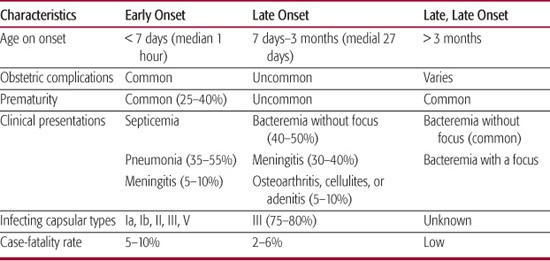

The clinical features of early-onset and later-onset group B streptococcal infections are shown in Table 286-1. Risk for early-onset infection is increased in the setting of maternal obstetric complications but term infants usually present with no risk factors other than maternal colonization. The three common clinical presentations for early-onset disease are septicemia without a focus, pneumonia, and meningitis. In excess of 75% of infants present with respiratory signs, including tachypnea, grunting, or cyanosis. Radiographic findings can be suggestive of surfactant deficiency, transient tachypnea, or congenital pneumonia. Other signs of early-onset infection are those common to neonatal sepsis, including temperature or vascular instability, poor feeding, and lethargy. Clinical signs suggesting meningeal involvement can be unapparent at the initial presentation, but seizures develop within 24 hours of presentation in 50% of infants with meningitis.

Table 286-1. Differential Characteristics of Early versus Later-Onset Group B Streptococcal Infections in Early Infancy

The three common presentations for late-onset infection are bacteremia without a focus of infection, meningitis, and osteoarthritis. The presentation for bacteremia without a focus can be insidious, with detection of infection when a sepsis evaluation is undertaken for an otherwise well-appearing febrile infant. Approximately one third of infants have a history of upper respiratory tract infection that heralds the development of bacteremia. For infants with meningitis, the initial signs of infection include fever, lethargy, irritability, poor feeding, and tachypnea. Some infants with late-onset meningitis have a fulminant presentation with seizures, poor perfusion, and septic shock developing over several hours. These infants have large numbers of bacteria visible in the cerebrospinal fluid Gram stain. They usually respond poorly to supportive care and tend to have a rapidly fatal outcome or, if they survive, to have major neurologic sequelae.

The third clinical presentation for late-onset disease is focal soft tissue infection or osteomyelitis. Group B streptococcal osteomyelitis usually has an indolent presentation and is characterized by single-bone involvement, often the proximal humerus. The signs of infection include swelling, erythema, and pain overlying the involved bone. Inflammatory signs tend to be less prominent than those of staphylococcal osteomyelitis, and group B streptococcal osteomyelitis can be misdiagnosed as Erb palsy. The hip, knee, or ankle joint is a common site of involvement for septic arthritis. Monoarticular involvement is the rule. Adenitis or cellulitis caused by group B streptococci usually is unilateral, and can involve facial or submandibular sites or the genital or inguinal region. Infants with cellulitis or adenitis often are bacteremic, but collections of purulence also yield the organism.

The designation late, late-onset infection is appropriate for infants older than 3 months of age who develop group B streptococcal sepsis. Late, late-onset infection can account for 20% of all late-onset disease. Those infants usually have a history of prematurity and prolonged hospitalization. Bacteremia without a focus is a common presentation.

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Isolation of group B streptococci from a normally sterile body site such as the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or site of focal infection such as bone, joint, or abscess fluid is diagnostic. Abnormalities of the white blood cell count, such as neutropenia or elevation of the ratio of immature to total neutrophils can be found in association with group B streptococcal infection, as well as in neonatal sepsis caused by other bacterial pathogens.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Penicillin G is the drug of choice for the treatment of group B streptococcal infection. Initial therapy for suspected infection should consist of ampicillin and an aminoglycoside. This combination is synergistic in vitro and in vivo for killing group B streptococci and provides broad-spectrum coverage for other potential pathogens in the newborn infant. When the diagnosis is confirmed, penicillin G alone should be continued to complete a 10-day course of therapy for sepsis or pneumonia and a 14-day minimum course of therapy for meningitis. A 2- to 3-week course of therapy is required for the treatment of group B streptococcal septic arthritis, and 3 to 4 weeks is required for treatment of osteomyelitis. The dose of penicillin for the treatment of group B streptococcal sepsis (200,000 U/kg/day) is lower than that recommended for the treatment of meningitis (400,000–500,000 U/kg/day). This higher dose is given for meningitis because the inoculum of bacteria in the cerebrospinal fluid can be as high as 10 million to 100 million colony-forming units per mL, and the goal of therapy is to exceed the minimal inhibitory concentration of the infecting isolate by a substantial margin.

A blood culture should be performed to document that antimicrobial therapy has achieved bloodstream sterility for infants with sepsis. For those with meningitis, a repeat lumbar puncture should be performed after 24 to 48 hours of therapy and before discontinuing therapy. The cerebrospinal fluid findings after 14 days of therapy can suggest inadequate resolution of the inflammatory response as indicated by a proportion of neutrophils exceeding 25% to 30% of the total, or a protein level in excess of 200 mg/dL. In this circumstance, it is advisable to continue antimicrobial therapy for an additional week and to repeat a lumbar puncture. It is rarely necessary to continue antibiotic treatment for longer than 3 weeks.

For infants with meningitis, an enhanced computed tomographic scan or magnetic resonance imaging study of the brain should be obtained before discontinuing antibiotic therapy. Diagnostic imaging gives additional information regarding the adequacy of resolution of cerebritis or ventriculitis. On occasion, cerebral imaging can reveal a previously unsuspected abscess or infarct that will influence the duration of therapy or prognosis.

Supportive care for infants with group B streptococcal infection includes attention to the details of fluid management, ventilation, and support of vascular volume. Seizures should be anticipated in infants with meningitis and controlled to limit brain edema and hypoxia. For infants with bone or joint infection, open or closed aspiration can be required to establish the diagnosis and to drain purulent material. A drainage procedure is required to preserve vascular supply of the hip or shoulder joints.

PROGNOSIS AND OUTCOMES

PROGNOSIS AND OUTCOMES

The mortality rate from group B streptococcal disease has declined markedly and now stands at 5% to 10% for early-onset disease. The mortality rate for late-onset disease ranges from 2% to 6%. Term infants surviving sepsis usually have no sequelae of infection. Premature infants with septic shock and periventricular leukomalacia can have residual neurologic impairment. There are no current data for the long-term outcome of term infants recovering from group B streptococcal meningitis. Approximately one third of infants treated for meningitis in the 1970s had serious neurologic sequelae. Infection, including that caused by group B streptococci, in extremely low-birth-weight infants is associated with poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in early childhood.4 Infants usually recover fully from bone or joint infection, but impairment of joint function or bone growth has occurred.

PREVENTION

PREVENTION

Recognition that intrapartum antibiotic administration could prevent early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal infection dates to the 1980s. National standards for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis were first implemented in 1996. These allowed for intervention to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal infection based on either maternal risk factors or maternal colonization. A program of active surveillance for invasive group B streptococcal disease noted a decline in the incidence of early-onset neonatal infections by 65%, from 1.7 per 1000 live births in 1993 to 0.6 per 1000 live births in 1998.5 Publication in 2002 of a population-based report finding that routine screening of all pregnant women at 35 to 37 weeks of gestation and administration of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis to all carriers prevented more cases of early-onset disease led to the current universal screening recommendations.6 With this culture-based approach, all pregnant women identified as carriers of group B streptococci by cultures performed at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation should receive intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. The average early-onset disease incidence in the era of universal culture-based screening from 2003 to 2005 was 0.33 cases per 1000 live births.7

A risk-based method for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is still recommended for women in whom group B streptococcal colonization status is not known at the onset of labor or rupture of membranes. Factors known to increase the risk for early-onset infection, including onset of labor or rupture of membranes before 37 weeks’ gestation, rupture of membranes 18 hours or more before delivery, or intrapartum fever warrant use of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. The current strategy also targets women with group B streptococcal bacteriuria during pregnancy, as well as women who have had a previous infant with invasive group B streptococcal infection.

Penicillin G is the antimicrobial of choice and ampicillin an alternative for intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. Cefazolin is recommended for women who are allergic to penicillin but at low risk for anaphylaxis.8Vancomycin use is reserved for penicillin-allergic women with a high risk for anaphylaxis for whom the susceptibility pattern of the group B streptococcal isolate does not permit use of clindamycin. Overall, an 80% decline in the incidence of early-onset disease has been documented since guidelines for intrapartum chemoprophylaxis became available.

Management of a neonate whose mother received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is dependent on the infant’s clinical status, the gestational age of the infant, and the duration of prophylaxis before delivery.8 Symptomatic infants and those born to mothers with chorioamnionitis should undergo full diagnostic evaluation and should receive empiric therapy. A limited evaluation and observation for at least 48 hours are indicated for asymptomatic infants less than 35 weeks’ gestation and for those infants whose mothers received chemoprophylaxis for less than 4 hours before delivery. Observation alone is indicated for asymptomatic infants of at least 35 weeks’ gestation whose mothers received chemoprophylaxis at least 4 hours prior to delivery.

Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is considered an interim intervention and its use has not reduced the incidence of late-onset group B streptococcal infection, which remains 0.3 to 0.4 cases per 1000 live births. A comprehensive program for prevention of group B streptococcal infection awaits the licensure of protein polysaccharide conjugate vaccines now under development.

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree