Introduction

Too many women still die in pregnancy and childbirth in developing countries. The estimated number of maternal deaths has been stable for many years, with between 515,000 and 536,000 maternal deaths per year, most of which occur in developing countries [1,2]. The international community has recognized the gravity of the situation by endorsing the improvement of maternal health as the fifth of its eight millennium development goals (MDG) [3]. International efforts are increasing to meet the MDG-5 target of reducing maternal mortality by 75% from 1990 to 2015 but there are strong signs that this target might not be met [2]. There are many reasons for this, including a lack of political will, human and financial resources, as well as some biologic and demographic factors, such as the impact of the HIV epidemic on women and health systems, and the continuing population growth.

This chapter will review the levels and causes of maternal mortality and morbidity in the developing world, the role of some medical disorders, other reasons for the high levels of maternal deaths and what can be done to improve maternal health in developing countries. It will also consider global issues in obstetric anesthesia.

Levels and causes of maternal mortality and morbidity

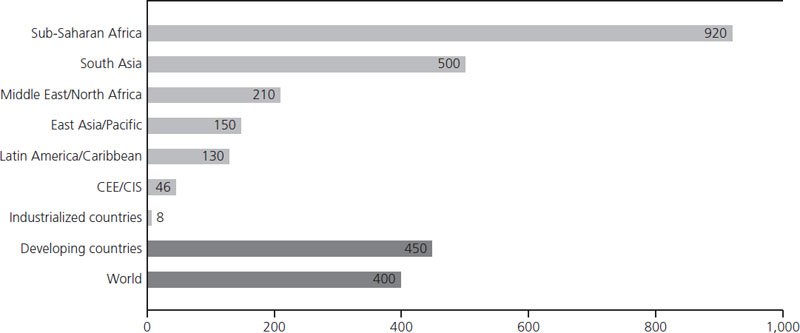

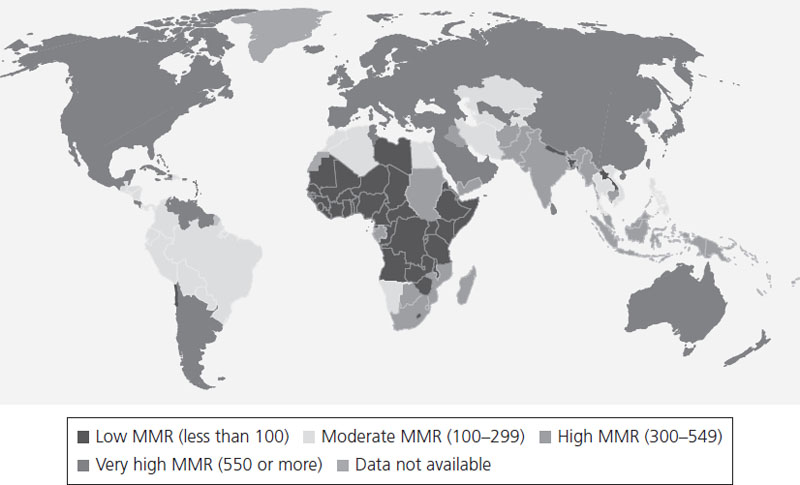

Of the 536,000 maternal deaths estimated in 2007, 99% occurred in developing countries (see Figures 25.1 and Figures 25.2). A further 9 million women have severe obstetric complications every year. The particularly high number of deaths in India (136,000) and Nigeria (37,000) can be attributed in part to the large populations of these countries. Another third of all maternal deaths take place in 11 countries, including Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Angola, China, Kenya, Indonesia and Uganda [4]. However, the risk of maternal death is highest in African countries and in Afghanistan. Women in Sierra Leone and Afghanistan have a lifetime risk of 1 in 6 of dying from a pregnancy, compared to 1 in 29,800 for women in Sweden [5] (see Table 25.1).

Table 25.1 Lifetime risk of maternal death by region, 2005

| Lifetime risk of maternal death | 1 in: |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 22 |

| Eastern/Southern Africa | 29 |

| West/Central Africa | 17 |

| Middle East/North Africa | 140 |

| South Asia | 59 |

| East Asia/Pacific | 350 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 280 |

| CEE/CIS | 1300 |

| Industrialized countries | 8000 |

| Developing countries | 76 |

| Least developed countries | 24 |

| World | 92 |

Figure 25.1 Maternal mortality ratios per 100,000 livebirths, by region, 2005. Reproduced with permission from World Health Organization, UNICEF, United Nations Population Fund and the World Bank, Maternal Mortality in 2005 (2007).

Figure 25.2 Maternal mortality ratios (MMR) per 100,000 livebirths, worldwide. Reproduced with permission from World Health Organization, UNICEF, Progress for Children: A Report Card on Maternal Mortality, Number 7, September 2008.

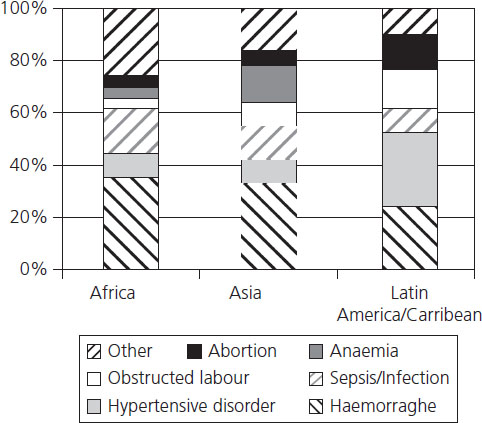

In poor countries, the causes of ill health and mortality in pregnancy can be difficult to establish because of the lack of diagnostic capability and vital registration. In addition, women may die at home or on the way to a provider and we have to rely on “verbal autopsies” to understand the reasons for their deaths. Available data indicate that the majority of deaths occur around the time of delivery and the most common causes are hemorrhage, infection, hypertensive disorders and obstructed labor (deaths associated with obstructed labor are classified separately even though obstructed labor usually causes death through infection, hemorrhage or uterine rupture) (Figure 25.3). Where diagnostic facilities exist, such as in South Africa, some causes of maternal mortality common in the “West,” such as pulmonary embolism, appear to be comparatively rare [6]. In addition, many women still die because of unsafe abortions where abortions are illegal or costly to obtain [7]. Beyond these, there are also reasons related to the status of women and their financial and geographic accessibility to services.

The role of medical disorders in maternal mortality

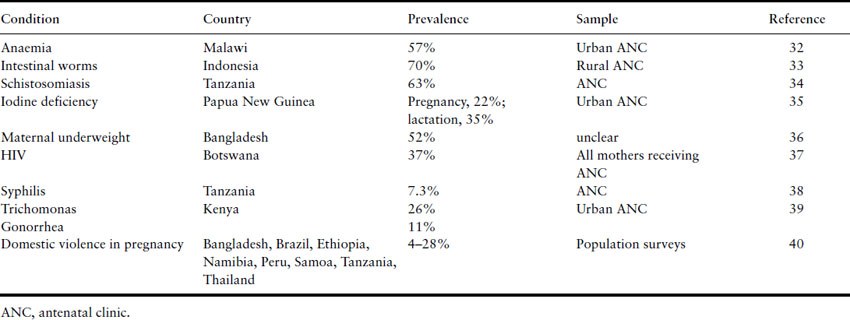

Medical problems have a high prevalence in developing countries and are often detected in pregnancy, as this is often one of the rare occasions when women, including the poorest, use formal services. Nonfatal conditions can be highly prevalent (Table 25.2).

Table 25.2 Selected examples of the frequency of chronic medical conditions in pregnancy

Indirect causes of maternal mortality such as anemia, malaria and HIV are increasingly recognized as important, particularly in Africa. Of these, maternal anemia is likely to be the most common medical problem. It usually results from nutritional deficiencies, intermittent (such as malaria) or chronic infections or hemoglobinopathies. Anemia is itself a cause of severe maternal morbidity [8] and can affect the case fatality rate of obstetric complications. Brabin et al. [9] estimated that the maternal mortality ratio for all-cause anemia was 40.8, 30.5 and 8.1 deaths per 100,000 livebirths for Africa, Asia and Latin America respectively.

In a hospital study of 251 maternal deaths in Zambia, 58% were caused by nonobstetric causes [10]. Of these, 30% were caused by malaria, 25% by tuberculosis and 22% by nonspecified chronic respiratory tract infections. While most studies, including those from Africa [6,11,12], continue to find that the majority of maternal deaths are caused by direct obstetric complications, a recent report from South Africa highlighted the importance of AIDS as the most common cause of maternal death in Durban [13]. In Malawi, maternal mortality level doubled between 1996 and 2000, reaching 1100 maternal deaths per 100,000 livebirths. Much of this is attributed to HIV/AIDS and its medical and social consequences.

In countries where malaria infection is common in pregnancy, such as in sub-Saharan Africa, one in four women has evidence of placental infection at delivery, and malaria-related maternal anemia, low birthweight, preterm delivery and infant and maternal mortality are prevalent [14]. Effective interventions, such as insecticide-treated bed nets and intermittent presumptive treatment, have the potential to reduce the risk of severe maternal anemia by 38%, low birthweights by 43% and perinatal mortality by 27% among women in their first and second pregnancies [14]. Multigravidae with HIV are also at increased risk from malaria [15] and malaria prevention may have to be aimed at all pregnant women in countries with a high HIV prevalence [4].

Reducing deaths from direct obstetric causes has been the focus of global initiatives such as Making Pregnancy Safer, with medical causes of ill health receiving less attention from the maternal health community. Integrating their management into routine obstetric services is important but requires careful attention, as they can create major disruption in service delivery and utilization. For example, well-resourced vertical HIV programs can attract the best staff away and undermine the ability of the routine services to provide skilled care [16]. Antenatal HIV screening programs often report a high loss to follow-up after HIV testing [17], and the fear of learning HIV results may contribute to poor uptake of intrapartum care for some of these women.

Current strategies to reduce maternal mortality

The provision of skilled birth attendants for all women in a health service setting and emergency obstetric care for those who need it are the two main strategies proposed for the reduction of maternal mortality (Box 25.1, Figure 25.4). Preventing unwanted pregnancies may also be able to avert around one-quarter of maternal deaths [3]. In addition to these, there are calls to reduce user fees and other financial or geographic barriers to enable access to obstetric services [18]. Countries which have successfully reduced maternal mortality are often middle-income countries. Lessons learnt from their success include the importance of increasing the professionalization of midwifery, improving access to skilled birth attendants and having an information system in place that monitors progress in maternal mortality [19].