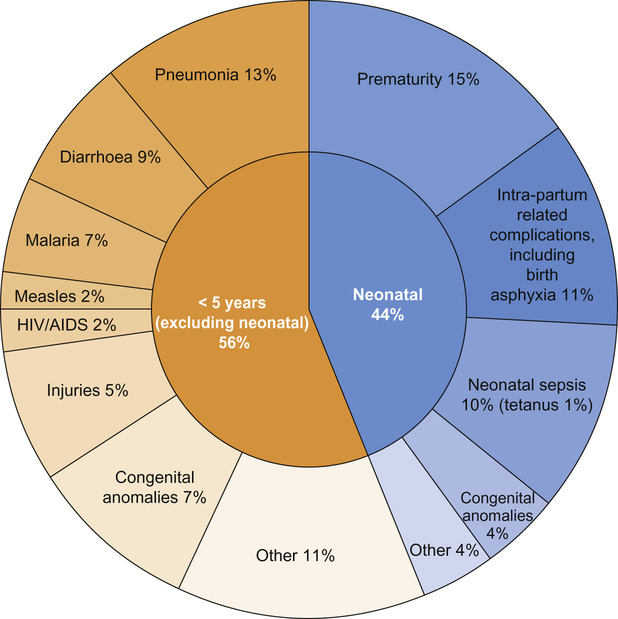

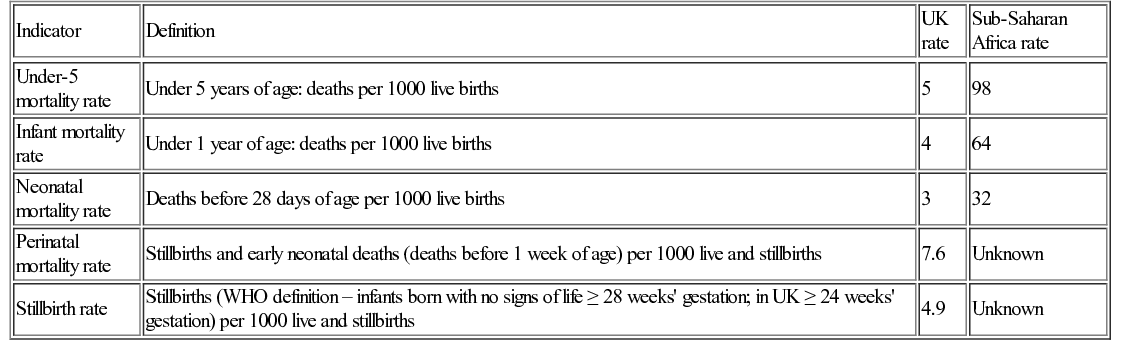

Dan Magnus, Anu Goenka, Bhanu Williams Large population size combined with high mortality rates mean almost half (49%) of child deaths occur in just five countries: India, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Pakistan, and China. Data capture and ascertainment of causes of death are fraught with difficulty in countries without proper systems in place for birth and death registration. Of the 12 million deaths in 1990 only 2.7% were medically certified. Many countries use techniques such as verbal autopsy, which involves questioning family members regarding the child’s symptoms immediately prior to death in order to retrospectively assign a diagnosis. Data suggest that the major causes of under-5 mortality are pneumonia (13%), preterm birth complications (15%), complications during birth (11%), diarrhoea (9%) and malaria (7%) (Fig. 33.1). Malnutrition is a major underlying cause of death and undernutrition is thought to contribute to 45% of under-5 deaths. There are important inter-country and inter-regional differences that need to be considered before planning specific public health interventions. For example, malaria is a more significant threat in Africa, where it is responsible for 15% of deaths in children under 5, compared with south-east Asia, where it contributes just 1% to under-5 mortality. Though neonatal causes still account for a substantial proportion of under-5 deaths in most low-resource settings, their contribution varies, e.g. 52% of under-5 deaths in south-east Asia, compared with 30% in Africa. In the post-neonatal period in South and Central America, it is injuries that are the single largest threat to under-5 survival, causing 16% of mortality. There are marked inter- and intra-country inequalities in child health. In 2012 the under-5 mortality rate was 147/1000 live births in Somalia, 56/1000 in India and 5/1000 in the United Kingdom. Marked inequalities in health also occur within countries. The poorer the child, the more likely they are to be exposed to risk factors for ill health. Unclean water and poor sanitation lead to diarrhoeal disease, while inadequate housing, air pollution and overcrowding promote the spread of respiratory pathogens. Poorer children are more likely to experience worse clinical outcomes for most illnesses compared with children from more wealthy backgrounds. This is partly because children living in poverty are more likely to be underweight and micronutrient deficient, have less resistance to disease, are less likely to be able to reach a health facility and less likely to receive adequate care. As well as poverty, mortality is higher in rural rather than urban areas and to a mother with little or no education. In addition, preventive public health measures such as vaccination, vitamin A supplementation and insecticide-treated net distribution tend to have the worst coverage amongst the poorest populations with the greatest need. Child health can be measured using a variety of numerical indicators. The most common, showing the rates for sub-Saharan Africa, are displayed in Table 33.1. Most child deaths are preventable through the scaling up of evidence-based child health interventions, adapted according to country-specific local disease epidemiology, with an emphasis on targeting the most vulnerable children. Educating girls is likely to have a positive impact on reducing child mortality and studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between maternal education and child mortality. However, it has been argued that maternal education may be a proxy measure of socio-economic status; once paternal education and access to piped water and sanitation is taken into consideration, the impact of maternal education has been shown to be less marked, although still significant. As well as rising wealth in many countries, the reduction in child deaths may be attributed to the implementation of child survival initiatives. Despite impressive reductions in child mortality in some countries, such as Rwanda and Bangladesh, the slowest improvements have been in West and Central Africa and it is unlikely that the MDG4 target will be met globally. The greatest gains in reducing post-neonatal under-5 mortality have occurred with the scaling up and improved coverage of preventative interventions, such as vaccinations and insecticide-treated nets for prevention of malaria. In stark contrast to the progress achieved in reducing post-neonatal under-5 mortality, efforts to reduce neonatal mortality have been hampered by a lack of a continuum between maternal and child care, which is discussed further below. Individual governments fund and facilitate important global health programmes, often through government organizations, e.g. USAID (United States Agency for International Development) and DFID (UK Department for International Development). However, it is intergovernmental organizations such as the United Nations or the International Labour Organization that often exert the greatest influence through cross-country collaborations and large, well-funded global partnerships. It is under the auspices of the United Nations that the World Health Organization, the World Bank and UNICEF are able to function and to deliver some of the most influential child health initiatives. The field-level implementation of such child health improvement initiatives is often achieved in collaboration with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), who rely on public and donor funding, e.g. Oxfam, and the Malaria Consortium. NGOs may operate internationally (e.g. Médecins Sans Frontières), nationally or regionally. Effective co-ordination between NGOs as well as government programmes are critical factors in determining the success of child health improvement initiatives. Governmental, intergovernmental and NGO partnerships only form part of the global picture on efforts to improve child health. Public–private partnerships also play an important role in financing and rolling out global health initiatives; GAVI (Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) is a good example of this. Private foundations, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, also provide significant investment and funding into global health programmes and research. Tomoka’s clinical presentation encompasses diarrhoeal disease and possibly pneumonia. They account for the majority of child deaths outside the neonatal period and the global burden is highest in Africa and south-east Asia. Pneumonia and diarrhoea are often considered together as they share common risk factors and programmatic solutions, including tackling poverty, undernutrition, poor hygiene, suboptimal breastfeeding, zinc deficiency as well as improving access to vitamin A and vaccination. The World Health Organization (WHO) has streamlined its case definitions to stratify the clinical severity of pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease. Pneumonia is now simply classified as ‘pneumonia’ and ‘severe pneumonia’ and diarrhoea is divided into syndromes (acute, persistent, bloody, etc.) with assessment of level of dehydration (none, some and severe). These classifications rely on objective clinical symptoms and signs that can be easily elicited by community health workers and staff working in primary care, facilitating the early referral of appropriate cases to secondary care. Oral rehydration solution (ORS) remains the cornerstone of management of diarrhea, coupled with continued feeding. Effective management of pneumonia relies largely on access to antibiotics. The treatment of hypoxaemia with oxygen has also been shown to reduce pneumonia deaths. Approximately one third of severe episodes of diarrhoea and pneumonia are preventable by vaccination. Despite increased vaccination coverage, the majority of pneumonia deaths are attributable to vaccine-preventable organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). Roll-out of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) lags behind Hib vaccine, despite the benefits of PCV even extending to children with viral pneumonia. Rotavirus vaccine continues to be introduced into the immunization schedules of many countries and effective coverage reduces mortality attributable to diarrhoea. Tomoka’s clinical presentation does not immediately suggest malaria but it is important to assess all febrile children who live in endemic areas for malaria. Most deaths from malaria occur in children under 5 and pregnant women. There has been some progress in reducing morbidity and mortality attributable to severe malaria, which is usually caused by Plasmodium falciparum. Plasmodium vivax and ovale cause less severe disease but have a liver hypnozoite stage that requires specific treatment to effect eradication. While Plasmodium malariae is seldom associated with severe disease, it can be associated with nephrotic syndrome. The WHO 2013 malaria report stated there were 627,000 deaths from malaria in 2010, 77% of which were in children under 5. The Roll Back Malaria Partnership has been coordinating international efforts since 1998 to scale up preventative diagnostic and therapeutic interventions with the overarching vision of freeing the world of the burden of malaria. Central to prevention of malaria is the use of long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs), which reduce the vector population of Anopheles mosquitoes. Currently, approximately 40% of children in sub-Saharan Africa sleep under an ITN. Households can be further protected from mosquitoes by indoor residual spraying (IRS) with insecticides. Various candidate malaria vaccines are in development, which, even if partially efficacious, could substantially reduce mortality and morbidity. The clinical presentation of malaria involves non-specific symptoms such as fever and headache. Clinical assessment alone carries the risks of both over-treatment and under-treatment. It is therefore essential to confirm the diagnosis before initiating treatment. The diagnosis of malaria in low-resource settings has been facilitated by the use of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), which are cost effective, require minimal training and can be used by community health workers. The management of acute severe malaria depends not only on prompt access to appropriate antimalarial drugs, but also effective treatment of hypoglycaemia, anaemia and convulsions. The superiority of artemisinin-based antimalarial treatment over quinine was demonstrated in two large multicentre trials involving more than 6500 children: the SEAQUAMAT study in south-east Asia and the AQUAMAT study in sub-Saharan Africa. The latter trial, a multicentre randomized controlled trial of children with severe malaria, showed significantly reduced mortality (relative risk reduction 22.5%, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 8.1–36.9; odds ratio for death 0.75, 95% CI 0.63–0.9) and reduced coma and seizures with artemisinin compared with quinine. Since the publication of these landmark studies, the WHO recommends artemisinin combination treatment (ACT) as first line in severe malaria. Artemisinin is combined with partner drugs to delay the development of drug resistance. Nonetheless, artemisinin resistance has emerged in south-east Asia. Exclusive formula feeding reduces the risk of HIV infection, although risk of death from gastroenteritis and other causes may be increased. Delivery by caesarean section reduces the risk but may not be indicated if the mother’s viral load is suppressed. Giving all women antiretroviral therapy irrespective of CD4 T-cell count or clinical staging is now WHO recommended policy. Tomoka’s mother died recently after a wasting illness. In a setting with high rates of HIV transmission, suspicion should be raised that Tomoka may have been vertically infected with HIV. Approximately 2 million children globally are currently living with HIV, most of whom acquired the infection perinatally. The rate of new paediatric infections has significantly declined, primarily due to the success of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) interventions. Maternal-to-child transmission of HIV without any of the preventative interventions listed in Box 33.1 can be between 30% and 40%; with intervention, this can be reduced to <1%. Tomoka’s HIV status should be ascertained as soon as possible. As Tomoka is 2 years old, a positive antibody test would indicate she is HIV-infected. HIV antibody is placentally transferred, and therefore a positive antibody test before the age of 18 months may indicate maternal HIV infection only. HIV proviral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the diagnostic test of choice in infants. At birth, HIV PCR has a low sensitivity (due to low viral load) and does not rule out infection. By 3 months, sensitivity is almost 100%. HIV infection is very unlikely if the child has two negative PCRs (one after 3 months) or two negative antibody tests if <12 months or one negative antibody test after 18 months. Tomoka needs to be assessed for the clinical features and complications of HIV infection. HIV infects CD4+ T cells, macrophages and neuronal cells, amongst others. Primary HIV infection is a mostly mild, mononucleosis-like illness, which resolves spontaneously, with the virus entering a phase of clinical latency. As infection progresses, the CD4+ cell count drops, determining the further clinical course of manifestation of opportunistic infections and malignancies. HIV can cause a chronic encephalopathy with developmental delay and faltering growth. The advance to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining diseases in children is highly variable; however, untreated infants and children have a high risk of progression to severe infections and death. In contrast, some vertically infected children may be asymptomatic into their teenage years. The CD4+ cell count and the HIV viral load are therefore the most important laboratory parameters to monitor in HIV-infected children. A randomized controlled trial (CHER trial) involved 377 HIV-positive infants assigned to receive early antiretroviral therapy (ART) at diagnosis in early infancy, or delayed ART until such time that immunological (CD4+ count) and clinical (WHO Clinical Stage) criteria were met. The study demonstrated a 75% reduction in mortality and disease progression with early antiretroviral therapy (ART) at diagnosis compared with delayed treatment. WHO guidelines now recommend the commencement of lifelong ART for all HIV-infected children and adolescents irrespective of CD4 count. Some countries have not yet incorporated this guidance owing to the cost. However, even prior to this revised WHO guidance, a significant number of HIV-infected children in low-resource settings found themselves within the ‘treatment gap’: in 2011, only 23% of eligible HIV-infected children were receiving ART compared with 51% of adults. The integration of HIV into the host genome (CD4+ lymphocytes) and subsequent virion replication is reliant on the error-prone reverse transcriptase enzyme. This process provides many opportunities for the virus to develop resistant mutants to ART. To minimize this, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), a combination of a minimum of 3 drugs, is used. First-line antiretroviral therapy involves 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (usually abacavir and lamivudine) and either a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (usually efavirenz in children over 3 years of age) or a protease inhibitor (usually lopinavir/ritonavir). Recent data from the ARROW study has shown it is possible to keep children well and virally suppressed in low-resource settings without regular laboratory testing for efficacy (CD4+ cell counts) and toxicity (haematology and biochemistry). The results of this study suggest that ART roll-out and adherence support services should take priority in low-resource settings where there is no comprehensive HIV care programme.

Global child health

Epidemiology and child survival

In which countries do most child deaths occur?

What are the major causes of child mortality worldwide?

What indicators can be used to measure child health and inequalities of child health?

Why have child deaths fallen?

International child health programmes

The role of international organizations in delivering programmes for improving global child health

Major threats to child survival

Pneumonia and diarrhoea

Malaria

HIV

Global child health

Chapter 33

Learning objectives

By the end of this chapter the reader should: