Genital Trauma

Diane F. Merritt

Accidental female genital injuries involving the vulva, labia, clitoris, vagina, and adjacent urogenital and anogenital structures require an organized approach for diagnosis, triage, and management. Genital injuries in children and adolescents may occur in the context of multiple organ system involvement (as in a motor vehicle accident) or as an isolated injury to the genitals (as in a straddle injury). Some incidents are accidents that are unlikely to ever occur again. Some children are victims of an isolated assault or repeated abuses. A thoughtful approach is necessary to be supportive to the child or teen who may be bleeding, in pain, and frightened, as well as for the patient’s parents or guardians who have concerns about the assessment and repair of an acute injury and the long-term significance for future reproduction.

Patient Assessment

The clinician has an obligation to assess whether the history provided is compatible with the injuries found on the physical examination. Inconsistencies between the history and physical examination should alert suspicion of sexual assault or abuse. Genital injuries may result in minor lacerations and bruising that heal rapidly, or profuse bleeding can occur due to the rich vascular supply in the genital area. Genital injuries alone rarely result in death but may result in chronic discomfort, dyspareunia, infertility, or fistula formation if unattended. Indications for surgical intervention and management will be discussed.

The approach to the injured child follows the traditional assessment of vital signs, airway, breathing, and circulation and evaluation of the sites and sources of trauma. In the case of genital trauma, the severity of the injury and the amount of bleeding determine where and how the examination should best take place. If the injury is not severe, the child may be examined in a doctor’s office or emergency department without sedation. Force or restraint should not be used for a genital examination. When the child or adolescent is unable or unwilling to allow an adequate examination to be accomplished, conscious sedation may be necessary. General anesthesia may allow for a better examination, assessment, and repair (1) (Table 16-1).

Examination in a Child or Adolescent

Evaluating the girl with active bleeding from the genital region following trauma can be challenging (see Chapter 1 for a review of examination techniques in the prepubertal child and adolescent). A study comparing the effectiveness of examination methods in the ability to help the clinician detect acute and nonacute injuries in pubertal and prepubertal girls assessed the three different examination methods: the supine labial separation method, the supine labial traction technique, and the prone knee–chest position (2,3,4,5). Each method had advantages, but by combining the methods the examiner had a greater chance of identifying additional signs of trauma than when using any one technique alone (2).

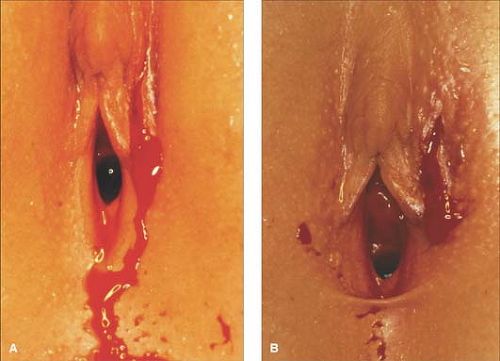

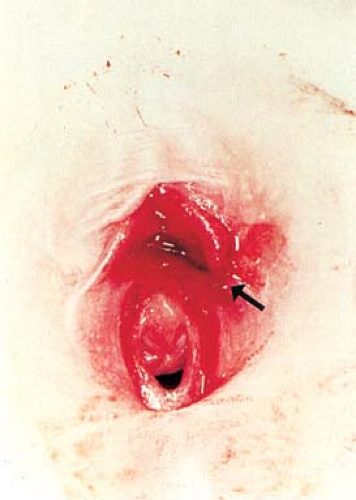

If there is an injury present, such as a vulvar hematoma, a laceration, or vaginal bleeding, the full extent of injury may difficult to determine, especially if the child is unwilling or unable to cooperate for an adequate examination. The bleeding from a vulvar laceration may be profuse and out of proportion to the size of the laceration. As can be seen in Figs. 16-1A and 16-2A, blood is present and it is initially difficult to identify the laceration until the area has been cleaned (Figs. 16-1B and 16-2B). Some suggestions for examining the child are to place 2% lidocaine jelly over the cut, place warm water in a syringe to irrigate the tissue gently, and/or irrigate using intravenous (IV) tubing and solution. The child can also assist by holding cool compresses with strong pressure. As noted in Fig. 16-3, the irrigation allows blood that may have collected to be washed away and the source of bleeding to be identified. If the bleeding is from an abrasion and it is oozing, it can often be treated with ice and compression. If the oozing continues, then Gelfoam or Surgicel can be applied.

In many situations, examination with sedation or under general anesthesia may be necessary. Standard vaginal speculums should not be used to examine a prepubertal child as they are designed for adults. A lighted nasal speculum may be of assistance without being traumatic (see Fig. 1-19). Vaginoscopy is an important tool used by the pediatric gynecologist, and depending on the age and level of cooperation of the child, this procedure may be done with or without anesthesia. Placement of a pediatric cystoscope into the vagina with gentle opposition of the labia provides fluid distension to allow adequate visualization of the vaginal vault in children. In this manner, injuries to the vagina can be assessed, and foreign objects may be found. When examining the vagina of an adolescent, the speculum selected for use should be the proper size for the patient.

Table 16-1 Indications for a Genital Examination Under Anesthesia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diagnosis

Etiology of Accidental Genital Injuries

Straddle Injury

Figure 16-2. A: Presence of blood after straddle injury. B: Identification of laceration after cleaning of the blood. (Courtesy of Marc R. Laufer, M.D.) |

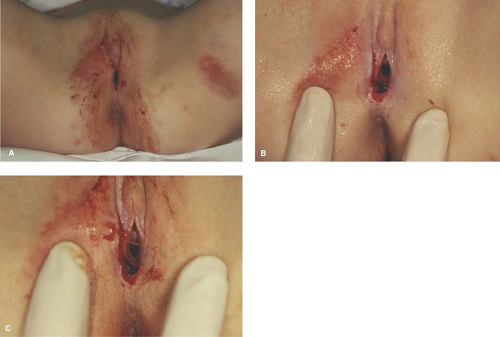

Straddle injuries occur when the soft tissues of the vulva are compressed between an object and the underlying bones of the pelvis. This trauma may result in ecchymoses (bruises), abrasions, and lacerations (see Figs. 16-1A & B and 16-2A & B). Extravasation of blood into the loose areolar tissue in the labia, along the vagina, the mons, or clitoral area, may cause ecchymosis (see Fig. 16-4) and/or hematoma to form (see Fig. 16-5). Examples of commonplace accidental straddle injuries include falling onto the frame of a bicycle, playground equipment, or piece of furniture. Nonpenetrating injuries usually involve the mons, clitoris, and labia and result in linear lacerations,

ecchymoses, and abrasions, sparing the hymen and vagina (see Figs. 16-6 and 16-7). Lacerations may require repair under local anesthesia, conscious sedation, or general anesthesia.

ecchymoses, and abrasions, sparing the hymen and vagina (see Figs. 16-6 and 16-7). Lacerations may require repair under local anesthesia, conscious sedation, or general anesthesia.

Vulvar Hematomas

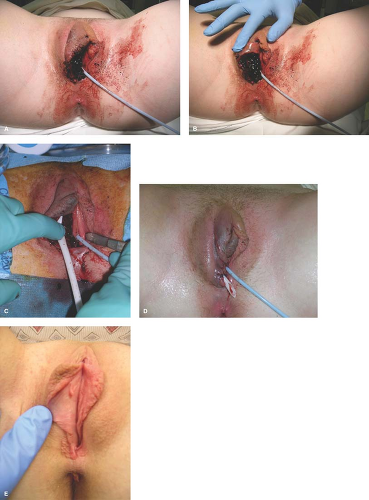

Vulvar hematomas (often sustained as a result of a straddle injury) can be very painful and may prevent a child or adolescent from urinating because of pain and swelling (see Fig. 16-5). The patient can be managed conservatively with immediate application of ice packs and limitations on physical activities if these conditions are met: (a) the hematoma is not large or expanding, (b) the perineal anatomy is not distorted, and (c) the patient has no difficulty emptying her bladder. In patients who are unable to void, placement of a Foley catheter is appropriate; otherwise, urinary retention will result (see Fig. 16-8). As the hematoma resolves, the blood will track along the fascial planes. The ecchymotic discoloration may take weeks to resolve. Pressure from an expanding hematoma may cause necrosis of the skin overlying the hematoma and result in eschar formation and tissue sloughing (3). The hematoma may spontaneously rupture and require evacuation, cleaning, debridement, and closure (see Fig. 16-9A–E) (see also Treatment page 301).

Figure 16-6. Ecchymoses and bleeding in a child following a straddle injury of the perineum. (Courtesy of Marc R. Laufer, M.D.) |

Figure 16-7. Same child as Fig. 16-6. Close-up of the vulva with laceration by the labia minora and periurethral tissues (arrow). Note the normal hymen. (Courtesy of Marc R. Laufer, M.D.) |

Accidental Penetrating Injuries

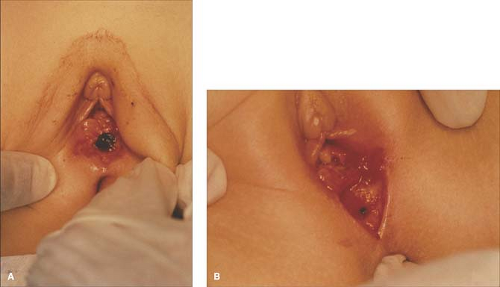

Penetrating injuries occur if the victim falls upon a sharp or pointed object and impales herself. Examples of household objects associated with impalement include in-lawn sprinkling systems, pipes, fence posts, trailer hitches, and furniture. The vagina, urethra and bladder, anus, rectum, and peritoneal cavity can also be pierced by sharp or pointed objects. The physical findings may vary and can appear to be quite minimal, yet the patient may have a more serious underlying injury only appreciated with adequate exposure (see Fig. 16-10A–C). In a report of 34 perineal impalements, several patterns emerged. Most injuries occurred in the home. Many children either slipped or fell in the bathroom on bathtub toys, soap dispensers, or the shower diverter valves or fell onto objects when climbing out of the tub or when running out of the bathroom after bathing. Slippery surfaces and the lack of protective clothing were stated to be the common contributing factors. Bedroom accidents occurred when children were jumping from one bed to another, a common play activity with obvious risk. Infants and children should be supervised in the bathtub as they may be at risk for drowning and scalding injuries if the bath water is too hot. They are also at risk for trauma from falls onto objects, but even the presence of supervising adults did not completely prevent these accidents (4). Accidental penetrating injuries may closely mimic the injuries associated with sexual assault, so corroboration of the events by an eyewitness is very helpful.

Accidental Vaginal Insufflation Injuries

Vaginal insufflation injuries occur when pressurized fluids enter the vagina. The walls may overdistend and tear, resulting in bleeding with significant blood loss. Such injuries may produce no sign of external genital trauma, and only careful vaginal examination (often under anesthesia) will reveal the source of bleeding and true extent of injury. This may occur accidently when girls fall while water skiing or riding jet skis, sliding down water chutes, and coming in direct contact with pool or spa jets. Children and women who participate in water sports can decrease their risk for vaginal insufflation injuries by using protective clothing such as neoprene wetsuits or cut-off jeans while water or jet skiing. When using a waterslide, head-first entries are usually forbidden to prevent head and neck injury, but it is also wise for girls to cross their ankles and/or to keep their feet together when entering water from a waterslide to prevent genital trauma (5,6,7).

Crush or Shear Injuries

Motor vehicle accidents are the most common mechanism of injury resulting in pelvic fractures for occupants, pedestrians, pedal cyclists, and motorcyclists. Shear forces can lead to lacerations when there is a fall associated with rapid abduction of the lower extremities or from the compressive forces associated with being run over by a motor vehicle. Vaginal lacerations with and without associated hymenal injuries have been reported (8,9). Falls or crush injuries during a collapse of a building due to structural problems or stresses from natural catastrophes (earthquakes), bombings, and warfare are the next leading cause of pelvic fractures that may lead to genitourinary injuries. Any time a pelvic fracture occurs, genital injuries may arise when fragments of the pelvic bone penetrate the vagina and lower urinary tract. This may lead to lacerations of the bladder, urethra, or vagina. The overall incidence of a genitourinary injury associated with a pelvic fracture was 3.62% in women (age not specified) in the National Trauma Data Bank. Predictors of bladder injury include widening of the symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joint. Fractures of the inferior and superior pubic rami and widening of the pubic symphysis were associated with urethral injuries (10).

Animal and Human Bites

Animal bites are rare but may be a cause of genital trauma. Most dog bites involve the extremities but in children more commonly involve the head and neck. Many dog bites are inflicted by the family pet or a neighbor’s animal. Human bites tend to occur in children as a result of playing or fighting, while in adults they are usually the result of aggressive behavior or participation in sports or during sexual activity. Mammalian bites may cause significant damage to delicate tissue of the genitalia. Microorganisms contained in saliva may cause infections resulting in local cellulitis or facilitate inoculation and transmission of communicable diseases. Genital bites are at high risk for infection because the loose subcutaneous tissue may facilitate bacterial spread (11,12,13).

Accidental and Inflicted Burns

Scalds are the leading cause of burn-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits for young children. Scalding due to hot tap water may be prevented by reducing the temperature settings in hot water tanks and testing the temperature of the water before placing a child in the bath. Recent awareness indicates that the bulk of scald injuries are non–tap water related and are associated with meal-time preparation of food (14,15,16).

Accidental immersion burns, where a child falls into a container of hot liquid, typically have irregular borders and nonuniform depth as the victim struggles to escape the hot liquid. This thrashing also causes splash marks, which, although they may sometimes be found in forced immersion, are more characteristic of accidental immersion. In accidental splash and spill burns, the head, neck, and trunk are commonly involved as the hot liquid is pulled or knocked over from a higher surface and spilled over by the child. Accidental contact burns are often patchy and superficial as the child quickly withdraws from the hot object or the falling object brushes across the skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree