13 Genital tract disorders

Vulvovaginal Conditions

Vaginitis: thrush

What is thrush?

Thrush (vulvovaginal candidiasis) is an infection caused by Candida species. Candida albicans accounts for 90% of infections and C. glabrata 5%. Less than 5% of cases are caused by C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. kefyr, C. guilliermondii or Saccharomyces cerevisiae.1 These organisms are all yeasts, that is they are microscopic single-celled fungi that reproduce by budding.

When is it most likely to occur?

the organism and specific immunological defects. However, the data supporting each of these factors are conflicting, and to date none is predictive of infection. The evidence related to each of these risk factors is summarised in Table 13.1.

TABLE 13.1 Epidemiological associations with vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC)

| Risk factor | Summary of the evidence |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | |

| Sexual factors | • VVC is not a sexually transmitted disease, as it can occur in celibate women and because Candida is considered part of normal vaginal flora.6 • Candida organisms, however, may be transmitted by vaginal sexual intercourse and other forms of sexual activity.115,116 |

| Oral contraceptive use | |

| Other methods of contraception | There is a higher risk with: |

| Sanitary pads and tampons | Studies have failed to establish a link between thrush and either douching, tampons or sanitary pads.122,123 |

| Tight-fitting clothing | Is anecdotal and unproven.6 |

| Dietary factors | Are anecdotal and unproven; one RCT is too small to draw any conclusions.124 |

What are the classic symptoms and signs?

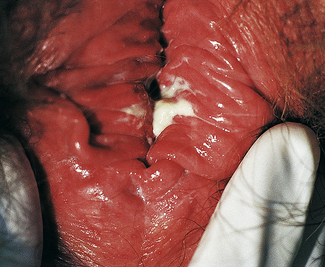

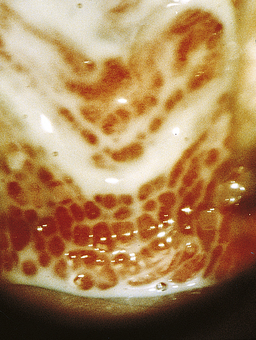

Classically, when women have thrush they complain of vulvovaginal itchiness. There may also be associated vaginal discharge that is white and resembling ‘curd’ or ‘cottage cheese’. As opposed to other forms of vaginitis, thrush is odourless. No symptoms, either individually or collectively, are diagnostic of thrush, as other diseases can cause a very similar pattern of symptoms. On examination, GPs may note vulval erythema with fissuring and the characteristic discharge. For examples of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), see Figures 13.1 and 13.2.

Is it necessary to obtain microbiological confirmation of candidiasis every time a woman presents with symptoms of thrush?

There are several ways to confirm a diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Vaginal cultures of swabs taken from the anterior fornix or the lateral vaginal wall will identify the organism. They are not routinely required, however, but should be considered in all symptomatic cases where microscopy and pH tests are inconclusive and in repeated treatment failures, recurrence or suspicion of non-albicans species.2

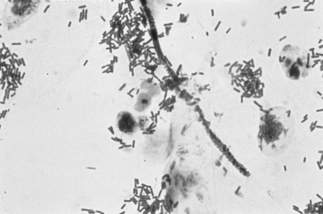

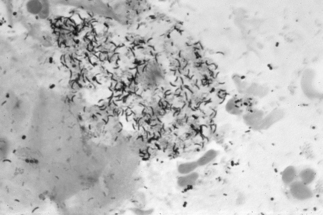

If a microscope is handy, microscopy with saline solution may show yeast budding or pseudohyphae in up to half of infections (Fig 13.3) but will still not pick up all cases. Non-albicans strains are more difficult to recognise.

What is the differential diagnosis of thrush?

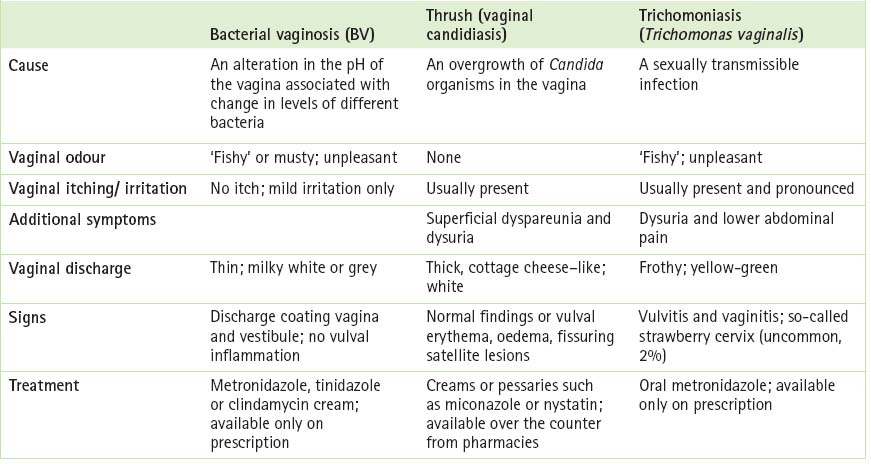

When looking at the differential diagnosis of thrush, GPs should consider other conditions that give rise to the two classic symptoms (pruritus and discharge). Herpes simplex, contact dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen sclerosus or allergies can give rise to acute pruritus vulvae, while trichomoniasis, bacterial vaginosis and, less commonly, the cervical infections Chlamydia or gonorrhoea (the discharge from these two organisms is actually cervical but may emerge from the introitus and appear to be vaginal in origin) can produce vaginal discharge. Table 13.2 (p 228) compares and contrasts three different forms of vaginitis. It is worth remembering that of the three bacterial vaginosis is the most common, followed by candidiasis and trichomoniasis.3

There are many different products available to manage acute thrush: which are the best to use?

Women and their doctors are often confused by the wide variety of products and formulations available for the treatment of candidiasis. Importantly, none of the available drugs are fungicidal. While they can reduce Candida to below detectable levels, they are not necessarily able to eradicate the organism completely. Azoles such as clotrimazole, econazole or miconazole (topical and oral) give an 80–95% clinical and mycological cure rate in acute thrush in non-pregnant women. By comparison, nystatin, an older product, gives a 70–90% cure rate under these circumstances.4

Differences in formulation are not thought to affect treatment outcome, and are more a function of patient preference.5

Women have the option of either topical or oral therapy. Creams are effective and give quicker initial relief than oral agents. Oral azoles, such as fluconazole or itraconazole as a 1-day course, are equally as effective as topicals (but a more expensive option), but they may have a delay in onset of action of 12–24 hours. They may also result in systemic side effects in 10% of users. These effects include gastrointestinal intolerance, headache and rashes, but are usually mild and transient.6 Oral ketoconazole is indicated only in cases not responsive to other agents. It should not be used for superficial fungal infections because of the potential risk of liver toxicity.

Routine use of corticosteroids is not recommended. In severe infections, low-potency topical corticosteroids may rapidly reduce local inflammation and burning, but the application of higher-dose corticosteroids often exacerbates the burning sensation.6

What duration of therapy is recommended?

Topical and oral azoles are effective in short courses. The term ‘short course’ can mean single dose, 3-day or sometimes even 5–7 day courses. As treatment courses have become shorter, the doses used have become higher, with the assumption that the total dose is more important than the duration of treatment, especially in uncomplicated infection.6

Many antifungal agents are available over the counter. Should women use these therapies rather than see a GP?

What about natural therapies like yoghurt?

There are currently no conclusive data on the effectiveness of Lactobacillus-containing yoghurt, administered either orally or vaginally, for the treatment or prevention of thrush.8,9 In addition, the use of oral or vaginal forms of Lactobacillus to prevent post-antibiotic vulvovaginitis10 has not been shown to be effective in a randomized, controlled trial.

What if treatment of an isolated episode fails?

As in any case of treatment failure, a GP should first ascertain that the patient has been compliant with the medication. If the answer is yes, the checklist given in Box 13.1 should be followed. If none of these factors are relevant, a longer course of treatment can be tried (e.g. 7 days if a 1- or 3-day treatment was initially used, or 14 days if a 7-day treatment was initially used). Another option is to combine oral with topical treatment.

BOX 13.1 Reasons for failure of treatment of an isolated episode of thrush

What approach should be taken if the woman gets recurrent thrush (>4 episodes per year)?

In these women, it is essential to be sure that what you are really dealing with is thrush. For this reason, with each individual episode vaginal swabs should be taken for microscopy and culture, and topical contact dermatitis, hypersensitivity or allergic reactions excluded. The patient should also be screened for diabetes, immunodeficiency, corticosteroid use and frequent antibiotic use.4

Recurrent thrush can be a very problematic condition that can prove frustrating to treat, not only for the woman but also for the doctor. The suggested approach is to use a two-phase line of attack. An induction period reduces the Candida and alleviates symptoms. A maintenance period then follows, aimed at preventing recurrence.1

Although the optimal induction period is not currently known, recurrent infections tend to respond less well to short courses of anti-mycotics (e.g. single-dose fluconazole or 7 days of a topical). Therefore, ‘induction’ therapy is recommended with at least 1 week of oral products or 1–2 weeks of topical products.1,6

The maintenance period usually lasts for 6 months. A wide variety of different regimens have been recommended. Commonly cited ones include oral fluconazole 100 mg weekly for 6 months, or topical clotrimazole (in the form of a pessary) 500 mg weekly for 6 months.1,4,6

Unfortunately cessation of therapy results in relapse in at least 50% of women4 and a small percentage of women may require maintenance azoles for years.6

If the woman is using a combined oral contraceptive pill, some advocate switching the pill to a less oestrogenic one (see Chapter 3). In women who are not on the pill who experience recurrent thrush in the week prior to the onset of menstruation, oral fluconazole can be used on a monthly basis at this time.

Another more novel way of treating recurrent or persistent candidiasis is through the use of Depo-Provera®.11 Its mechanism of action is thought to be through its action of lowering oestradiol levels in the blood.

Is there any difference to management if the woman is pregnant or breastfeeding?

While thrush in pregnancy does not pose a risk to the fetus, it can cause considerable distress to the mother, because of persistence and recurrence. Asymptomatic colonisation with Candida species is higher in pregnancy (30–40%) and symptomatic candidosis is more prevalent throughout pregnancy.4

Topical azoles can safely be used in pregnancy. Clotrimazole is safe and effective. Miconazole and econazole can also be used and systemic absorption is negligible.12 Topical imidazole appears to be more effective than nystatin for treating symptomatic vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy. Treatments for 7 days may be necessary in pregnancy rather than the shorter courses more commonly used in non-pregnant women.13

Vaginitis: bacterial vaginosis

What exactly is bacterial vaginosis?

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is regarded as a fairly innocuous condition but it is the most common cause of vaginal discharge in women of childbearing age.14 The condition comes about when the normal hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus spp in the vagina is replaced by high concentrations of polymicrobial anaerobic bacteria. Women with bacterial vaginosis have complex and diverse vaginal infections, with many newly recognised species, including three bacteria in the Clostridiales order that are highly specific for bacterial vaginosis.15

BV ‘infection’ is a superficial one and is characterised by a lack of an inflammatory reaction and an absence of white cells in the discharge. This is why it is called a ‘vaginosis’ rather than a ‘vaginitis’. Previously the condition was known as Gardnerella vaginosis, because the organism Gardnerella vaginalis was commonly found in increased numbers in women with BV. However, it is not always present and has been reported in 16–42% of women with no signs or symptoms of vaginitis.16

What causes BV?

The literature has yet to show a real understanding of why BV occurs or how its recurrence can be stopped. The prevalence of BV varies with ethnicity (with rates of >33% in studies of Indigenous Australian women,17 and >50% in sub-Saharan African and African American women18), low socioeconomic status, a history of STDs, large numbers of sexual partners and a recent change in sexual partner. A high concordance of BV between women in lesbian relationships has also been reported.19

What is the significance of BV?

BV puts women at greater risk of developing other STIs, especially HIV.20 It can also lead to infective complications after surgery and premature birth (see p 233).

What are the symptoms of BV?

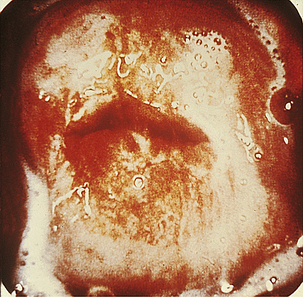

Characteristically, women notice a thin, watery, homogenous discharge and an associated malodorous, ‘fishy’ smell (Figs 13.4 and 13.5). Often women can be completely asymptomatic. Characterised by an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria, it can occur and remit spontaneously.21

How is the diagnosis of BV made?

Examination of a woman with a complaint of a vaginal discharge or odour should include an evaluation for the clinical criteria (Amsel criteria)23 of BV (Box 13.2). At least three of these criteria must be present for a diagnosis of BV to be made.

BOX 13.2 Diagnostic criteria for bacterial vaginosis

Lastly, a wet mount of vaginal secretions should be tested to look for ‘clue’ cells. These are epithelial cells covered with G. vaginalis (Fig 13.6, p 232). They have a ground glass appearance and are the clues to the diagnosis of BV. By comparison, vaginal epithelial cells from women without BV have clear borders.

The Gram stain is the single, best laboratory test for diagnosis of BV. This method is preferable to culture because it has greater specificity. To prepare a vaginal smear for a Gram stain, a swab should be used to obtain vaginal fluid and cells from the vaginal wall (not the cervix). This swab should then be rolled across a slide and the material allowed to air-dry. There is no need to fix the smear prior to shipment to the laboratory: air-dried vaginal smears are stable at room temperature for months.

Is BV a sexually transmissible infection?

This is a very controversial issue. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis has found that there are associations between BV and increasing number of partners and a decrease in the incidence of condom use.24 However, there is opposition to this view because:

How is BV treated?

There are two options, either oral or topical treatment. First-line treatment of BV is either oral metronidazole (Flagyl) or tinidazole (Fasigyn) or the use of the vaginal cream clindamycin. These treatments are outlined in Box 13.3. Oral and topical therapy have the same efficacy, with cure rates of 70–90%.30 There is no evidence of teratogenicity of metronidazole in women during the first trimester of pregnancy.31–33 Regardless of which therapy is used, BV will recur in over half of the women in which treatment seemed effective.34 In this group it may be helpful to suggest condom use because of the associated decreased incidence of BV among female partners35 (perhaps because the pH of semen does not affect the vaginal ecosystem when condoms are used).

If a woman has no symptoms (many women have possible BV reported as an incidental finding on smear), should it be formally diagnosed and treated?

Recent research has shown that BV is associated with post-abortion pelvic inflammatory disease36 and post-hysterectomy vaginal cuff cellulitis.37 In pregnancy BV is associated with:

What is the association between BV and premature birth?

There are many and varied reasons why premature birth occurs. In up to 40% of cases, the cause is infection,45 with one of the strongest correlations with premature delivery being the existence of chorioamnionitis. This condition is also associated with failure of the tocolytic drug therapy that is used to delay or reverse the onset of labour. Examination of the amniotic fluid or chorioamniotic membranes of women who experience premature labour and premature rupture of membranes commonly finds evidence of infection manifested by the presence of organisms and inflammatory cytokines. Most of these microorganisms are thought to come from the vagina, particularly from women with BV.46

In typical obstetric populations, BV is prevalent in 10–30% of women.47 In a study of high-risk pregnant women, the prevalence was 50%.48 Studies looking at the association between BV in pregnancy and premature delivery have found relative risks ranging from 0 to 6.9. A recently published meta-analysis reviewed 19 studies looking at the association and found a 60% increased risk of premature delivery given the presence of BV, or an odds ratio of 1.6.49

This association has enormous clinical significance, but the association between BV and premature delivery is not clear-cut. It is thought that BV is only a marker for something else—presumably subclinical infection of the upper genital tract that then leads to premature delivery. Interestingly, spontaneous regression of BV during pregnancy as assessed by vaginal Gram stain does not appear to improve perinatal outcomes.50

Does treatment of BV decrease the risk of premature birth?

A Cochrane review51 has found that antibiotic therapy was highly effective in eradicating infection during pregnancy. They also found that, while treating BV during pregnancy resulted in a trend towards fewer births before 37 weeks’ gestation, it only significantly prevented births before 37 weeks’ gestation in the subgroup of women with a previous premature birth (odds ratio 0.37, 95% CI 0.23–0.60).

What guidelines for the management of this problem currently exist?

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommends that women be screened for BV during pregnancy only if they have a history of premature delivery or if they weigh less than 50 kg before the commencement of the pregnancy.52 On the basis of current evidence, ACOG maintains that screening for other women is not warranted.

Vaginitis: trichomoniasis

How can a diagnosis be made?

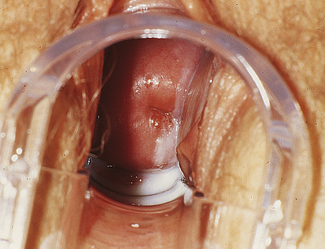

Classically vaginal discharge is frothy, yellowy-green in colour and malodorous (Figs 13.7 and 13.8, p 234). The vulva and vagina appear inflamed (in contrast to BV) and a ‘strawberry cervix’ (this appearance is due to punctuate haemorrhages) is visible to the naked eye in 2% of patients.

The clinical features are not sufficiently sensitive to diagnose Trichomonas vaginalis infection.53 Diagnosis should therefore occur either through microscopy or culture of the organism. A swab is taken from the pool of discharge in the posterior fornix of the vagina. If a microscope is to hand, the Trichomonas can be seen as a unicellular flagellated protozoan in a saline wet mount. Culture requires a special medium. Sometimes Trichomonas infection is detected on a Pap smear as an incidental finding. Cervical cytology has a sensitivity of only 60–80% for Trichomonas, however, and a false positive rate of 30%, so its use as a diagnostic test is not recommended.54

What treatment is there?

Some strains of T. vaginalis have diminished susceptibility to metronidazole. Thankfully, most of these will respond to higher doses of metronidazole. If treatment fails with either regimen, the patient should be re-treated with metronidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days. If treatment fails again, the patient should be treated with a single, 2 g dose of metronidazole once a day for 3–5 days.55

What if the patient is pregnant?

Like BV, vaginal trichomoniasis has been associated with enhanced HIV transmission and increased adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as premature rupture of the membranes, preterm delivery, and low birth weight.56 Unfortunately a study examining the consequences of treatment of pregnant women with metronidazole resulted in increased morbidity.57

Herpes

What causes herpes?

The herpes simplex virus (HSV) belongs to the Herpetoviridae family, the properties of which are described in Box 13.4. It gains access to sensory neurones through abraded skin, causes latency and persists for the life of the host. There are two types of HSV, type 1 and 2. Both types can cause oral and/or genital herpes, although type 1 favours oral sites and type 2 genital infections.

How common is it?

The prevalence and epidemiology of the two types of HSV are quite different. HSV1, traditionally associated with oral infection, is prevalent in about 20% of children <5 years of age and the prevalence rises in a linear fashion thereafter.58 Eventually about 80% of people acquire HSV1.59 Interestingly only a third report ever having a ‘cold sore’.60 HSV1 genital herpes may be increasing in incidence, especially in younger people. In a Melbourne study, the proportion of first-episode genital herpes due to HSV1 increased from 15.8 to 34.9% of cases between 1980 and 2003.61 The rising incidence of HSV1 genital herpes could be the result of decreasing HSV1 seroprevalence and consequently a larger susceptible population and/or an increase in the popularity of oral sex.62

In contrast HSV2 is extremely rare in young people, with most disease being acquired between the ages of 15 and 40, as would be expected of an STD. Approximately 20–25% of sexually active people contract HSV2 during this time.63 Prior infection with HSV1 modifies the clinical manifestations of first infection by HSV2.64

What is the natural history of herpes?

One of the key features of herpes infection that has become more evident in recent years is the fact that the majority of herpes remains undiagnosed, probably because most outbreaks are not recognised and are only mildly symptomatic.65 Less than 25% of HSV2 seropositive people report a clinical diagnosis of genital herpes.60 However, 50–60% of ‘asymptomatic’ HSV2 seropositive people can identify clinical outbreaks if taught how to do so.66 Reasons for failure to diagnose genital herpes infection are given in Box 13.5.