3 Contraception

Combined Hormonal Contraception

Contraception for adolescents

Are there any legal issues to consider when prescribing the pill to adolescents?

contraception before becoming sexually active. She is also seeking the GP’s confidentiality and is fearful of the consequences of her parents finding out that she has come to see the GP, let alone the fact that she is planning to become sexually active.

In Sarah’s situation, the ‘mature minor rule’ applies and is based on an English legal precedent called the Gillick case. This case ran in the English courts in 1985. Mrs Gillick was a Roman Catholic mother of 10 children, who was affronted by the prospect of one of her under-age daughters being prescribed the oral contraceptive pill without her mother’s consent.

What form of contraceptive would you choose?

Many would argue that Sarah should just use a condom with emergency contraception as a back up (see p 46). However, even in experienced users, condoms can break and/or spillage occur. In the inexperienced hands of teenagers, where lubrication is not always prevalent, condom failure is likely to occur more often. Sarah may also have problems in getting her partner to accept condom use. Sex may also occur after alcohol or drug use. For all of these reasons, Sarah is best off using hormonal contraception as well as condoms. However, GPs should make adolescents aware of the existence of emergency contraception and how to access it, should they need it in the future.

Sarah would therefore benefit from hormonal contraception either in the form of a combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) or a long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) such as Implanon® or Depo Provera®. While the COCP has both contraceptive and non-contraceptive benefits (Table 3.1), LARCs offer higher efficacy because they are not as user-dependent. It is important, however, to offer Sarah a choice of contraceptive methods so that she is informed and able to choose the method that suits her best. For example, if she has a chaotic lifestyle or a poor memory and is fearful of forgetting to take the pill every day (especially if the packet has to be kept out of sight of her parents), then Depo-Provera® or Implanon® is probably the more suitable alternative.

TABLE 3.1 Benefits of the combined oral contraceptive pill

| Contraceptive benefits | Other benefits |

|---|---|

Summary of key points

Dispelling myths about the pill

How commonly are myths about the pill believed?

CASE STUDY: ‘I’ve heard the pill causes cancer.’

‘I’ve heard the pill causes cancer.’

‘I don’t want to put on any weight.’

‘My skin is pimply enough as it is and I don’t want it to get worse.’

It is important also to explain to young women why it is that all these myths have arisen about the pill. The pills that women take today are not the same as the ones taken by their mothers. The dosage has come down from 100 mg of oestrogen, which used to make women vomit and was related to strokes and heart disease, to 30 mg or less. The COCP is one of the most researched pharmaceutical products in the world. Provided women are healthy, have normal blood pressure and do not smoke, these events are no more likely to occur than if they were not on the pill.1

How safe is the pill?

An British study of 46,000 women (which began in 1968) tracked users of oral contraceptive pills containing 50 mg of oestrogen for 25 years.2 This study showed that over the entire follow-up period the risk of death from all causes was similar in never-users of the pill to ever-users. For women who had stopped using the pill more than 10 years previously, there were no significant increases or decreases either overall or for any specific cause of death.

Does the pill cause cancer?

The pill acts in a preventive fashion against ovarian and endometrial cancer. Use of combined oral contraception decreases the risk of a woman developing ovarian cancer by 40%. The longer a woman uses the pill, the greater the effects. Ovarian cancer is associated with many factors, such as family history, decreased parity, late age of menopause and early menarche. It is thought that women who do not bear children have a 2–2.5-fold increased risk of developing ovarian cancer, and this is perhaps because of the increased opportunities for monthly follicular development. The pill suppresses follicular activity and is therefore associated with a relative risk of 0.6 in ever-users and 0.4 in women who use the pill for >5 years.3 The increasing protection with increased duration of use has been confirmed in other studies.4

Endometrial cancer occurs in 0.1 per 100,000 women aged 20–24 and in 12 or more women per 100,000 in those aged 40–44. The risk factors for this cancer are similar to those of ovarian cancer and include obesity, nulliparity, early menarche and late menopause, and the administration of unopposed oestrogen. The effect on endometrial cancer of taking the pill is similar to that of ovarian cancer, with use of the pill decreasing risk of endometrial cancer by 50%. This effect is maintained for at least 20 years after discontinuation of the pill.4

While the explanation is unclear, several studies have found that ever-users of the COCP have a 60% reduction in bowel cancer.5

Unfortunately, use of the pill may increase the risk of a woman developing breast cancer. The relationship between breast cancer and the pill has now been the subject of numerous studies. Collectively they suggest the following:6

It is important to assist women to gain some perspective about this increased risk, given the degree of awareness of breast cancer in the community. This can be done using the information given in Table 3.2 (p 42). Given that the incidence of breast cancer increases with age naturally (1 in 500 women have breast cancer by age 35 compared with 1 in 100 by age 45 and 1 in 12 by age 75), the risk attributable to COCP use by women increases in older women.7

TABLE 3.2 Excess number of breast cancer cases/10,000 women who had used the COCP for 5 years and were followed up for 10 years after stopping, compared with never-users

| COCP use for 5 years up to age: | Excess cases of breast cancer in 10,000 women |

|---|---|

| 20 | 0.5 |

| 25 | 1.5 |

| 30 | 5 |

| 35 | 10 |

| 40 | 20 |

| 45 | 30 |

(From Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer98)

The COCP appears also to increase the risk of cervical cancer (five extra cases per 100,000 women per year), but it is unclear whether this is a causal relationship.8 Long-duration follow-up studies certainly show a clear effect of duration of pill use, with the odds ratio of developing cervical cancer being 2.9 after 4 years of COCP use and 6.1 after 8 years.4 Despite this, it is important to remember that HPV is the primary carcinogen and that smoking is probably a more important co-factor than the COCP.9

Regarding other cancers, liver cancer might be increased by the pill (but it is a rare cancer anyway), and the role of the COCP in the development of malignant melanoma remains controversial.7

Are women who take the pill at increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events?

The COCP magnifies all of these underlying risks and usage of the pill should be carefully considered in women who have any of these risk factors.6

Is the pill associated with weight gain?

Another major misconception held by young women concerns weight. Every patient can recount stories of friends who put on ‘massive’ amounts of weight when on the pill. A recent systematic review, however, has found no evidence supporting a causal association between combination oral contraceptives, or a combination contraceptive skin patch, and weight gain.10

In conclusion

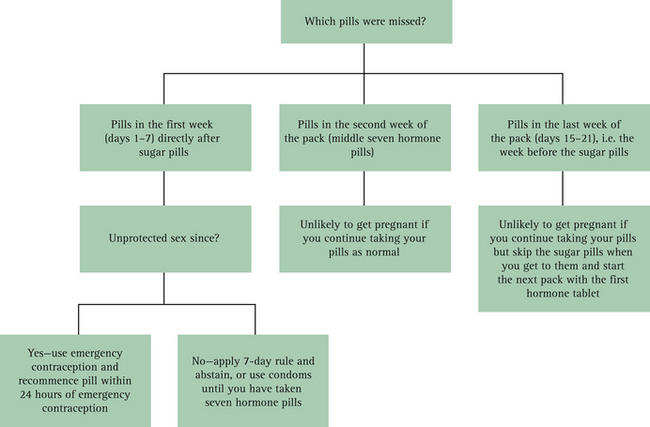

Explaining the beneficial effects of COCP use is only one aspect of contraceptive counselling. It is important to take the time to explain the mechanism of action of the pill and to ensure that the woman knows how to take it correctly and understands the importance of not missing pills. What to do when a pill is missed should be explained, together with the fact that the most dangerous ones to miss are the hormone pills taken immediately before and after the sugar pills. This information should be accompanied by written instructions that the woman can refer to in a time of need.

Summary of key points

Starting a woman on the pill

What are the contraindications to the pill?

Before starting a woman on the pill, a GP must rule out any contraindications to its use. These contraindications have been classified by the World Health Organization11 into four categories (Box 3.1, p 44).

BOX 3.1 Contraindications to use of the COCP

(From WHO11)

What examination needs to be carried out before a woman starts the pill?

The only examination routinely required prior to first prescription of the COCP is blood pressure. In asymptomatic women, breast and pelvic examinations are unnecessary. Blood tests are also unnecessary unless there is a specific clinical indication.12

What messages need to be conveyed to women starting the COCP for the first time?

The quick-start method

To overcome this problem the ‘quick-start’ method has been devised.13 It involves starting the COCP on the day of the consultation, regardless of the patient’s menstrual cycle day, and means that no counselling about when to begin is necessary. The woman swallows her first pill in the clinic immediately after prescription, and continues to take a pill each day. All patients who receive the first pill during the clinic visit first undergo a urine pregnancy test and emergency contraception if needed and receive at least one pack of the COCP so that they do not have to go to a pharmacy to fill a prescription before beginning. The quick-start method is outlined in Box 3.2.

Missed pills

After asking the young woman to show you the most dangerous times to miss a pill, explain that this is in fact immediately before and after the sugar pills. This fits in nicely with the analogy of putting the ovaries to sleep. If the pills before or after the sugar pills are missed, the ‘pill-free interval’ is lengthened, thereby allowing the ovaries to wake up and release an egg. (The pill-free interval has been set arbitrarily at 7 days by manufacturers in order to replicate a normal 28-day cycle, except for Yaz, which has a 4-day pill-free interval—see Box 3.3.) If more than 7 days go by (i.e. if more than seven pills are missed), there is a chance that ovulation, and therefore pregnancy, could occur.

There has recently been some controversy over whether advice to women regarding missed pills should differ according to the oestrogen dose in the pill.9,14 The simplest advice (erring on the side of caution) for pills that have the traditional 21 active pills and 7 sugar pills is outlined in Box 3.4 and Figure 3.1 (p 46). Where a pill like Yaz (24 active pills and 4 sugar pills) is used, the advice for missed pills is dependent on whether more than 7 pills have been missed.

BOX 3.4 Missed pills

One pill missed (late by up to 24 hours)

More than one pill missed (>24 hours)

As well as 1–3 (above), avoid sex or use condoms for 7 days.

In a case of vomiting or diarrhoea

Should a woman vomit within 2 hours of taking a pill, the absorption of the hormones is questionable and another active pill should be taken (from the end of the pack). If the replacement pill and a second one taken 25–26 hours later fails to stay down then the missed pill rules should be followed. Diarrhoea without vomiting is not a problem unless it is ‘cholera-like’.9

When antibiotics are prescribed

No study has reliably investigated if the efficacy of the COCP is reduced with concurrent antibiotic use. Short-term antibiotic use alters gut flora and reduces the enterohepatic circulation of oestrogen. Gut flora recovers after 3 weeks of antibiotic use.15

If a woman starting the COCP has been using a non-liver-enzyme-inducing antibiotic for ≥3 weeks, no additional contraceptive behaviour is required unless the antibiotic is changed, when it should be managed as for short courses (<3 weeks) of antibiotic use. Women using the COCP who are given a short course (<3 weeks) of non-liver-enzyme-inducing antibiotics should be advised to use additional contraceptive protection while taking the antibiotic and for 7 days after stopping the antibiotic.16

Side effects

One of the most common reasons women avoid using the pill is fear of weight gain. This is especially true of adolescents, who can sometimes be obsessed with their weight and dieting. While progestogens such as levonorgestrel may stimulate the appetite, young women starting contraception are often at the end of their pubertal growth spurt and may be putting on weight anyway. In a study of women who used the COCP for 12 cycles, approximately equal numbers of women gained or lost more than 2 kg in weight, with the majority (74%) being unchanged or within ± 2 kg of their baseline weight before starting the COCP.17 Other side effects, such as nausea and break-through bleeding, usually lessen with time, and young women starting the pill should be advised to continue for at least 3 months in order to see whether commonly experienced side effects dissipate. Many young women chop and change their pills too quickly. Such moves result in added problems that make them declare that they are unable to use the pill. This is a shame, as they have 30 or so potentially reproductive years ahead of them and may well need to use the pill in the future.

Drug interactions with the pill

What is the mechanism of drug interaction with the pill?

Some anticonvulsants are well known to induce liver enzymes that cause the breakdown of oestrogens

and progestins. Anticonvulsants most likely to have this effect are:

The argument becomes interesting because the bioavailability of orally administered ethinyloestradiol is usually 40%, but varies markedly from 20% to 65% in different individuals. This variation in initial bioavailability may account for the sporadic cases of pregnancy that occur with concurrent antibiotic use. For example, if the woman had a low background availability of ethinyloestradiol, coupled with a large enterohepatic circulation and gut flora sensitive to the antibiotic being prescribed, she might be more likely to fall pregnant. The problem is that the very small subgroup of women who may have all these factors concurrently cannot be identified by any routine diagnostic tests.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree