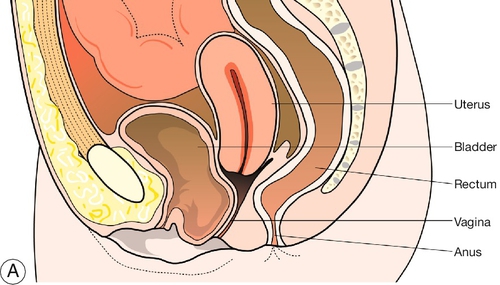

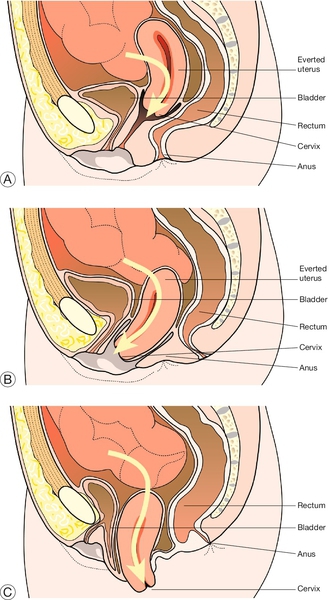

16 Uterovaginal prolapse is described as the descent of one or more of the pelvic organs (urethra, bladder, uterus, Pouch of Douglas (POD) and rectum) into the vagina. While prolapse of a single organ independently can happen, typically more than one organ will be involved. This is because all of the organs which can prolapse (with the exception of the POD) are attached either directly or indirectly to the pelvic floor musculature. Of women who have had children, 30% will develop prolapse. The lifetime risk of requiring surgery for prolapse is around 11%. The aetiology of genital prolapse is pelvic floor muscle weakness. Other contributing factors are listed in Box 16.1. In addition, obesity, chronic cough and constipation, which all raise intra-abdominal pressure, can aggravate the condition. Childbirth results in trauma to the pelvic floor and loss of tissue support to the female pelvic organs. While direct trauma can happen at the time of vaginal delivery, the biggest problem in the long term is pudendal nerve damage, which causes a gradual weakening of the fascia and neuromuscular tissue of the pelvic floor. A prolonged labour, in particular a prolonged second stage and a large baby are the biggest risk factors. The pudendal nerve is crushed against the bony pelvis during labour and the longer the patient is in labour, the worse the damage is likely to be. This explains why prolapse seldom happens immediately after childbirth but rather many years later. The same aetiology is responsible for stress urinary incontinence, which demonstrates the same time scale. While the aetiological problem starts in labour, some of the factors mentioned below, along with obesity, are typically the triggers for the development of symptomatic prolapse. The menopausal state, characterized by oestrogen deficiency and loss of connective tissue strength, is a causative factor in the development of prolapse. Congenital weakness and neurological deficiency of the tissues account for prolapse in a small proportion of women. Rarely, children may be born with prolapse or they may develop significant prolapse during childhood. There may also be anatomical variants that may make certain women more susceptible to prolapse in later life. Although surgery is often used to treat prolapse, it may be responsible for a small number of cases. Suprapubic surgical procedures for urinary incontinence (e.g. Burch colposuspension – see History box) alter the anatomy such that the bladder neck is approximated behind the symphysis pubis. This increases gravitational effects on the pouch of Douglas, prolapse of which leads to enterocele. Prolapse of the vaginal vault is a not uncommon long-term consequence of a hysterectomy. Genetic factors have been implicated in the development of prolapse. It is uncommon, for example, in the African population, possibly related in some way to the different collagen content of tissues. The classification of prolapse, and the main symptoms, are summarized in Table 16.1. Table 16.1 Types of genital prolapse a In addition to the general symptoms of discomfort, dragging, the feeling of a ‘lump’, and, rarely, coital problems. A urethrocele is descent of the part of the anterior vaginal wall which is fused to the urethra. This is approximately the first 3–4 cm of the anterior wall superior to the urethral meatus. Any descent of this tissue may alter the urethrovesical angle and disrupt the continence mechanism, predisposing to stress urinary incontinence (SUI). The bladder base lies immediately above this. Descent of this area is termed a cystocele (Fig. 16.1). Urethroceles and cystoceles may prolapse together, and when both are present the term cystourethrocele is used. The cervix occupies the upper third of the vagina and descends when there is uterine prolapse. Uterine prolapse may be described as first, second or third degree (Fig. 16.2):

Genital prolapse

Introduction

Aetiology

Childbirth

Menopause

Congenital

Gynaecological surgery

Genetic

Classification

Original position of organs

Prolapse

Symptomsa

Anterior

Urethrocele

Cystocele

Stress urinary incontinence

Poor bladder emptying, residual urine, frequency and urinary infection

Central

Cervix/uterus (1st-, 2nd-, 3rd-degree and procidentia) and vaginal vault

Bleeding and/or discharge from ulceration in association with procidentia

Backache

Posterior

Enterocele (POD)

Rectocele

Pressure, backache

Difficulty in bowel emptying

Urethrocele

Cystocele

Uterus and cervix

![]() first degree – there is descent of the uterus and cervix within the vagina but the cervix does not reach the introitus

first degree – there is descent of the uterus and cervix within the vagina but the cervix does not reach the introitus

![]() second degree – descent of the cervix to the level of the introitus

second degree – descent of the cervix to the level of the introitus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree