Essentials of Diagnosis

- • Most individuals with genital herpes are unaware of the infection but are able to transmit it to others.

- • Type-specific serology allows reliable differentiation of chronic type 1 from type 2 infection.

- • Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by diagnostic testing of the genital lesion (culture or polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) or a type-specific serologic assay.

General Considerations

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections are endemic in the United States and are a cause of recurrent genital and oral ulcerative disease. Genital herpes infection can be caused by type 2 virus (HSV-2), or less frequently by type 1 (HSV-1). Although most infections are asymptomatic, genital HSV infection, whether type 1 or 2, can cause vesicular and ulcerative disease in adults and severe systemic disease in neonates and immunocompromised individuals. Genital HSV infection increases the risk of HIV acquisition in infected persons.

HSV-2 transmission is almost always sexual, whereas HSV-1 is usually transmitted through nonsexual skin-to-skin contact. Current estimates place the incidence of HSV-2 infection at more than 1.5 million cases annually. In the general population, HSV-2 seroprevalence is low for persons younger than 12 years of age, rises sharply following onset of sexual activity, and peaks by the early 40s. HSV-2 seroprevalence in the United States rose 30% between 1978 and 1991 to 21.7%. The overwhelming majority of individuals with genital HSV infection have undiagnosed initial infections and unrecognized recurrences. Orolabial HSV-2 infection is rare and is almost always associated with genital infection.

HSV-1 infection frequently occurs as orolabial infection in childhood, and approximately 20% of children younger than 5 years of age are seropositive. The seroprevalence of HSV-1 rises almost linearly with increasing age to approximately 70%. In the general population over the past decade, HSV-1 has become an increasingly common cause of genital infection, with an estimated 50% of newly acquired genital herpes attributable to it in some populations.

Pathogenesis

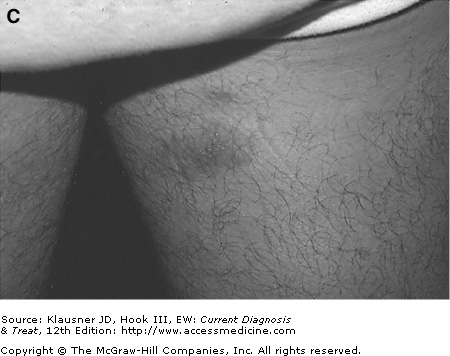

Primary HSV infection occurs at mucosal sites of inoculation (see Figure 14–1), with retrograde infection propagating to sensory nerve ganglia. Following resolution of primary infection, HSV enters a latent state in sensory nerve ganglia from which reactivation may occur to cause active infection at any mucosal sites innervated by the nerve ganglia.

During primary HSV infection, natural killer cells are important effectors of immunity. Their activation depends on the production of several cytokines in response to the infection. These cytokines also have direct and indirect effects that are important for limiting replication of the virus. As the immune response matures, HSV clearance from infected tissues is T-cell mediated, involving cytokine-mediated effector mechanisms and direct cytolysis of virus-infected cells. In mice and humans, both CD4 and CD8 T cells are important in resolution of infection. Antibody may play a limited role in controlling HSV infection as well.

The efficiency of the immune response appears to influence the quantity of virus establishing latency in the ganglia. Although the elements contributing to this control are incompletely known, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) is likely to be important. IFN-γ activates antiviral genes that inhibit HSV replication and may be required for early decrease in local HSV viral titers. However, it appears from murine models that both IFN-γ and T-cell response can maintain viral latency and clear peripheral infections.

Prevention

There are multiple proven ways to prevent the acquisition and transmission of genital herpes. There are no “right” answers for prevention, and each patient must determine those best suited for his or her lifestyle. All patients diagnosed with genital herpes should be educated to recognize genital herpes outbreaks and given the option of daily suppressive therapy as a means to reduce genital herpes transmission. Measures for reducing transmission and acquisition of genital herpes include:

- 1. Disclosure of genital herpes infection to new partners. Although it may be difficult at first for patients to inform new partners that they have genital herpes, medical providers should encourage this important and necessary step to allow sex partners to make informed choices and, if appropriate, modify sexual practices to reduce the risk of transmission.

- 2. Abstinence during outbreaks. Once educated about the typically mild signs and symptoms of outbreaks, most patients are able to recognize symptomatic outbreaks.

- 3. Correct and consistent condom use. Male latex condom use can reduce transmission, especially during the first 6–12 months after initial infection.

- 4. Selection of partners with similar HSV serologic status or a history of genital herpes.

- 5. Chronic suppressive therapy. A recent major study demonstrated a 70% reduction in HSV transmission by infected patients using daily suppressive therapy. The reduction in disease and infection transmission may be attributable to both reduction of genital herpes recurrences and reduction of subclinical shedding.

Clinical Findings

Genital infection with HSV can be differentiated into five categories: first recognized episode, primary first episode, nonprimary first episode, recurrent episode, and subclinical shedding. Symptoms and signs characteristic of each are described below.

The clinical diagnosis of a first episode versus recurrent episodes is unreliable. For the patient, the first recognized episode is an “initial” infection, whether it is a first episode or recurrent infection. The only way to classify a first episode with certainty is to document serologic conversion, but such classification usually serves little clinical purpose. All first recognized episodes can be safely managed as a newly acquired infection given the safety profile of currently recommended oral antiviral medications for HSV. Although both increased frequency of outbreaks and viral shedding are more likely with recent acquisition of infection, recommendations for daily suppressive therapy are based on the patient’s desire to control disease (ie, outbreaks) or reduce the risk of transmission, or both.

This refers to infection with either HSV-1 or HSV-2 in an individual who has never had infection with a herpes simplex virus. In immunocompetent hosts, this event often goes unrecognized.

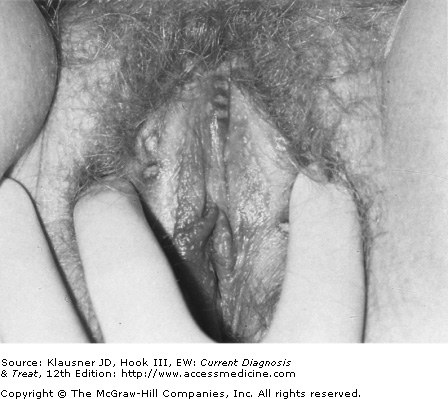

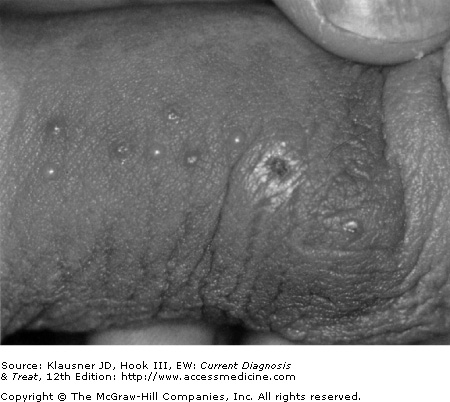

After an incubation period of several days (average, 4 days; range, 1–14 days), a small papule appears that quickly evolves into a vesicle within 24 hours. Vesicles can be clear or pustular, are multiple, and rapidly evolve into shallow, nonindurated, painful ulcers (see Figure 14–2). The appearance of lesions can be associated with dysuria, inguinal lymphadenitis, vaginal discharge, and cervicitis. In primary infection, systemic symptoms including myalgias, malaise, fever, and other “flu-like” symptoms may be associated with the appearance of genital lesions. In the typical presentation, signs or symptoms are minimal and usually are not recognized as primary genital herpes.

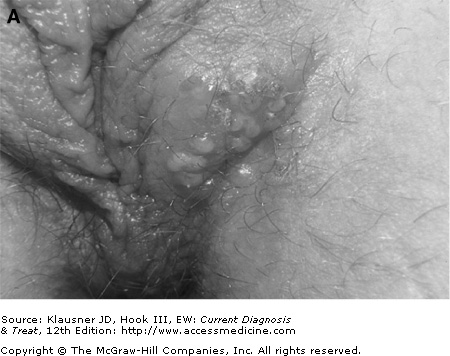

Crops of lesions may occur over 1–2 weeks, and crusting and healing of lesions requires an additional 1–2 weeks (see Figure 14–3).

This refers to infection in individuals who have had a previous infection with either HSV type. The typical scenario is an individual with prior HSV-1 orolabial infection who subsequently acquires new genital HSV-2 infection. Typically, the first genital herpes outbreak tends to be less severe clinically than a true primary episode due to an existing, partial humoral and cellular immunity. Fewer lesions appear, pain and systemic symptoms are less, and lesion resolution is more rapid than with a primary first episode. The first episode usually resolves within 5–7 days. Nonprimary first episodes are clinically similar to recurrent disease and are often mistaken for recurrent genital herpes, if they are recognized at all.