Gastrointestinal Infections

Matthew B. Laurens and Michael S. Donnenberg

Gastrointestinal infections account for a large burden of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide. In developing countries, gastrointestinal infections are the second leading cause of death in children, resulting in an estimated 2 to 3 million fatalities annually.1 The incidence of diarrhea peaks between 6 and 12 months of age, with an annual incidence of 4.8 episodes per child.2 In the United States, acute diarrhea leads to more than 1.5 million outpatient visits, 200,000 hospitalizations, and 300 deaths among children per year.2

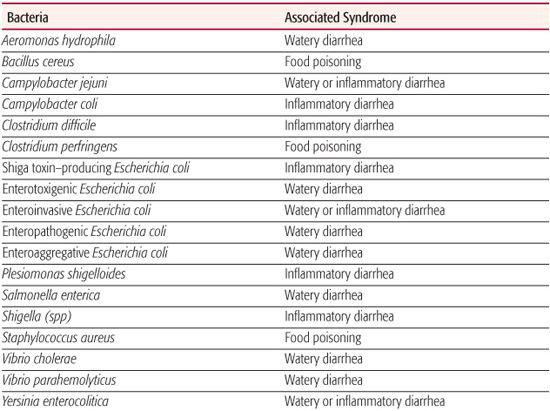

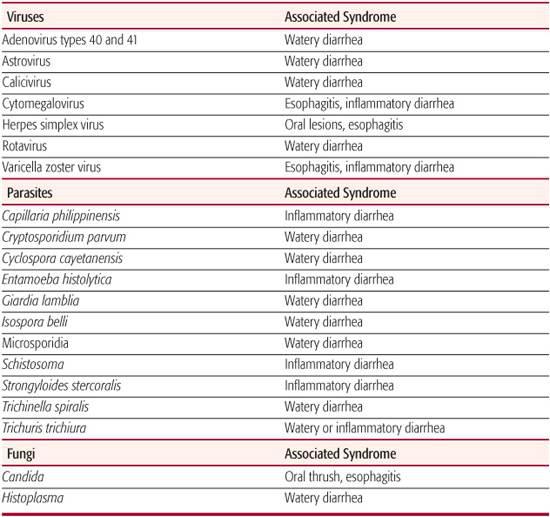

Table 236-1 lists the common gastrointestinal pathogens in children and the common syndromes they cause. This chapter will focus on common gastrointestinal infections in the pediatric population, including acute watery diarrhea, acute inflammatory diarrhea. Specific infections causing esophagitis are discussed in Chapter 394; and those causing gastritis or peptic ulcer disease in Chapter 409.

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Acute watery diarrhea is a ubiquitous symptom in childhood. Good global data on the etiology of diarrhea is lacking, but worldwide, rotavirus is the most common etiologic agent of acute gastroenteritis in children.3 Rotavirus is seasonal in temperate climates, with peak incidence occurring in late winter, but shows no seasonal pattern in the tropics. The highest incidence of rotavirus infection occurs in children ages 6 months to 2 years. Rotavirus is spread via the fecal-oral route and can be acquired nosocomially. The incubation period for rotavirus is 1 to 3 days.

Other important viral causes of acute watery diarrhea in the United States include adenovirus and norovirus. Adenovirus gastroenteritis is predominantly caused by types 40 and 41 in children younger than 2. Adenovirus gastroenteritis is seen year-round. The incubation period is 3 to 10 days. Norovirus, a type of calicivirus, causes acute watery diarrhea that is generally associated with outbreaks in which the virus is spread via the fecal-oral route, with an incubation period of 1 to 2 days. Other causes of acute watery diarrhea include astrovirus and other caliciviruses. In developing countries, bacterial infections account for many cases of watery diarrhea. Important bacterial causes of watery diarrhea include Vibrio cholerae, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E coli (EPEC), and enteroaggregative E coli (EAEC).

Table 236–1. Gastrointestinal Infections in Children: Common Pathogens and Commonly Associated Clinical Syndromes

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Rotavirus is excreted in high concentration in stool (perhaps more than 109 virions per gram). The virus infects mature enterocytes of the small intestinal villi to induce watery diarrhea by inhibiting the sodium/glucose cotransport system and causing a net chloride secretion.5 The virus also decreases the disaccharidase enzyme activity of the small intestinal brush border to cause malabsorption of carbohydrates and nutrients. The end result is a combined osmotic and secretory diarrhea that does not contain blood.

Gastrointestinal adenoviruses, unlike strains found in the respiratory tract, have enhanced the ability to attach to gastric and intestinal epithelium in an acidic environment because of their basic charge and stability in the face of intestinal enzymatic activity.6 Patients may continue to shed the virus in stool months after the acute infection has resolved. Caliciviruses do not grow in culture, which has made characterization of their properties and pathogenesis difficult. Acute calicivirus infection is associated with villous changes in the jejunum and infiltration of monocytes in the mucosal layer. Like rotavirus, caliciviruses have been associated with decreased intestinal enzymatic activity.

Bacteria that produce enterotoxins without cellular invasion cause increased intestinal secretion, but may also cause histological damage. V cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 cause severe watery diarrhea by producing an enterotoxin (cholera toxin) that indirectly activates adenylyl cyclase. Elevated levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP) induce chloride secretion in crypt cells through the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, and sodium and water follow passively. In villous cells, sodium and chloride transport from the lumen into the intestinal cells is inhibited. ETEC strains colonize the epithelium via surface adhesins known as colonization factor antigens and produce either a heat-labile toxin (LT), a heat-stable toxin (ST), or both toxins. Heat-labile toxin has a structure very similar to that of cholera toxin and an identical mechanism of action, whereas heat-stable toxin directly stimulates apical guanylyl cyclase. Enteropathogenic E coli strains cause severe diarrhea and vomiting in infants in developing countries. Typical enteropathogenic E coli strains produce bundle-forming pili that enable the bacteria to adhere in clusters to epithelial cells, whereas all enteropathogenic E coli strains inject a receptor known as Tir into the host cell membrane using a type III secretion system (T3SS). A surface protein called intimin binds to Tir and the host cell forms a cuplike pedestal composed of cytoskeletal proteins upon which the bacteria rest. The loss of intestinal microvilli and intimate adherence induced by enteropathogenic E coli is known as the attaching and effacing effect. Enteroaggregative E coli produces pili that cause a distinctive aggregative pattern of adherence and enterotoxins including Pet and EAST 1, which resembles heat-stable toxin.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The etiology of watery diarrhea cannot be determined on the basis of clinical features because there is much overlap in symptoms and signs. Moreover, agents that cause inflammatory diarrhea can also induce watery diarrhea without fever or mucus or blood in the stool. In addition to acute, watery diarrhea, symptoms may include vomiting and fever. Rotavirus infection is more likely to cause watery diarrhea in young infants, and severe vomiting is the predominant symptom in those > 2 years of age.7 Rotavirus is commonly associated with fever, and cough and coryza may precede the onset of intestinal symptoms. Rotavirus stool rarely contains blood, mucus, or white blood cells. The dehydration that accompanies rotavirus diarrhea is often associated with increased losses of sodium and chloride, isotonic dehydration, and a compensated metabolic acidosis. The most common complication is dehydration, and children with malnutrition seem to be at highest risk. Vomiting often lasts 2 to 3 days and diarrhea 5 to 8 days.

Enteric adenoviruses are generally characterized by fever and diarrhea, occasionally with vomiting. Diarrhea tends to be more prolonged when compared to rotavirus infections, lasting 9 days on average. Respiratory symptoms may also accompany enteric adenovirus symptoms.

Calicivirus infection is generally associated with an extremely abrupt onset of vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, headache, low-grade fever, myalgia, anorexia, and malaise. These last only 24 to 48 hours.

Enteric adenoviruses are generally characterized by fever and diarrhea, occasionally with vomiting. Diarrhea tends to be more prolonged when compared to rotavirus infections, lasting 9 days on average. Respiratory symptoms may also accompany enteric adenovirus symptoms.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Rapid diagnosis of rotavirus and adenovirus can be accomplished by solid-phase immunoassays of stool. Diagnosis of caliciviruses can be accomplished using nucleic acid sequence-based amplification or enzyme immunoassay detection.8 Diagnosis of V cholerae infection in the appropriate geographical and clinical context can be made by culture, while the diarrheagenic E coli causing watery diarrhea can only be confirmed using tissue culture assays, gene probing, or PCR in reference laboratories. When watery diarrhea is persistent, agents of inflammatory diarrhea should be investigated with appropriate testing (see below). Nonenteric infections and conditions can occasionally present with diarrhea and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

The cornerstone of acute watery diarrhea management is oral rehydration therapy. The evaluation and treatment of diarrhea is discussed in detail in Chapter 385.

PREVENTION

PREVENTION

Because most causes of acute, watery diarrhea are transmitted via the fecal-oral route, the availability of safe drinking water and routine hand-washing are the foundations of prevention. Also important to the prevention of rotavirus is the recent approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of a new live, orally administered vaccine, RotaTeq, administered as a 3-dose series between ages 6 and 32 weeks. RotaTeq is a pentavalent vaccine that contains five reassortant viruses and was tested in more than 70,000 children before licen-sure.9 Rotarix, a second vaccine used to prevent rotavirus, is derived from an attenuated human strain of rotavirus and is currently under evaluation for FDA licensure. Both vaccines are currently used in the Americas and Europe and have proven highly effective in preventing rotavirus disease. They are also safe from the possible complication of intussusception, which was associated with a rotavirus vaccine licensed by the FDA from 1998 to 1999.

ACUTE INFLAMMATORY DIARRHEA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Inflammatory diarrhea often results from infections caused by bacteria that are transmitted via the oral-fecal route. Risk factors for inflammatory diarrhea include day care and hospital settings, antibiotic use, travel to endemic areas, and animal exposure.

Campylobacter jejuni is the most common cause of inflammatory diarrhea in the United States and especially affects children younger than age 5 and young adults (see Chapter 256). The incubation period is usually 2 to 5 days, but may be up to 10 days. Other important causes of inflammatory diarrhea in the United States include enterohemorrhagic E coli (EHEC) and other Shiga toxin–producing E coli (STEC), Shigella, Salmonella enterica, Yersinia enterocolitica, Entamoeba histolytica, and Clostridium difficile (see Chapters 250, 283, 293, and 341).

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Inflammatory diarrhea is associated with abnormal stools that may contain blood, pus, mucus, and fecal leukocytes. Other associated symptoms include fever, chills, vomiting, abdominal pain and/or cramping, tenesmus, and frequent defecation. The clinical characteristics for each pathogen may allow for subtle differentiation of the etiology. Abdominal pain that mimics appendicitis may be caused by Campylobacter or Yersinia. Patients with Shiga toxin–producing E coli typically have bloody diarrhea without fever. Typhoid fever is associated with high fever that lasts for weeks if untreated, classically with a discordantly low heart rate. C difficile colitis may be associated with hypoalbuminemia in 25% of patients.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Because of the public health implications of outbreak identification and control, stool specimens should be sent for testing for Shiga toxin–producing E coli from all patients with bloody diarrhea. Although O157:H7 enterohemorrhagic E coli strains can be identified on sorbitol-Mac-Conkey medium, other Shiga toxin–producing E coli strains cannot, and therefore a stool enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Shiga toxins is extremely helpful. For patients with bloody diarrhea and those with suspected inflammatory diarrhea without blood, stool culture for Campylobacter, Shigella, and Salmonella is indicated. If a child has diarrhea and risk factors for C difficile, such as recent antibiotic use or hospitalization, then stool should be tested for the presence of C difficile toxins, although these can be present in stool specimens of children without gastrointestinal disease, especially infants and young children.12 Children with chronic diarrhea or a history of travel to a developing country or who are immunocompromised should have specimens tested for ova and parasites, including Entamoeba histolytica. Evaluation and treatment of the child with diarrhea is further described also in Chapter 385, but we will reemphasize here that only some of the causes of bacterial enteritis require specific therapy, and antimicrobial therapy is contraindicated for E coli O157:H7. The differential diagnosis of acute, inflammatory diarrhea includes other causes of colitis such as Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, necrotizing enterocolitis, intussusception, and food allergy.

PREVENTION

PREVENTION

Preventive efforts aimed at causes of inflammatory diarrhea target appropriate food preparation; hygiene; vaccination for preventable causes, including typhoid fever vaccination before travel to endemic areas; and control and containment measures to prevent the spread of disease. In daycare centers, careful attention should focus on good hygiene when changing diapers. For hospitalized patients with inflammatory diarrhea, contact precautions should be strictly followed and meticulous hand hygiene should be maintained to prevent nosocomial transmission. Wider acceptance of food irradiation could make the food supply much safer and prevent many cases of infection.

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree