Gastrointestinal Disorders Associated with Immunodeficiency

Richard J. Noel

Children with primary or acquired immunodeficiency are at increased risk for infectious and inflammatory gastrointestinal disorders.1 The risk and severity of infection depends on the type of immunodeficiency. Individuals with deficiencies of antibody response are predisposed to extracellular bacterial infections and intestinal pathogens. Patients with deficiencies of T cells are predisposed to both intracellular and extracellular infections. In addition, patients with primary immunodeficiencies are more prone to develop autoimmune disorders because of their decreased ability to distinguish self-organisms from foreign organisms. Autoimmune diseases and celiac disease are more common in the IgA-deficient patients.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Gastrointestinal disorders in children with immunodeficiencies can be associated with infectious (viruses, bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, or protozoa) and noninfectious disorders (autoimmune and alloimmune). Dysmotility, malabsorption, and malnutrition can be associated with any of these disorders. In addition, medical treatments prescribed for children with immunodeficiencies may have important gastrointestinal complications.

Gastrointestinal Infections

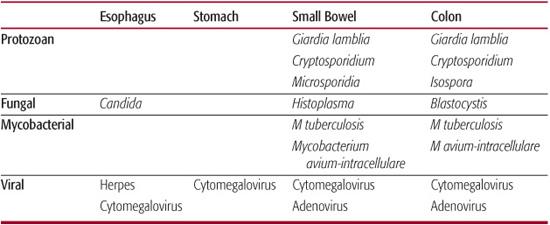

The pandemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) has heightened our awareness of opportunistic infections, most of which have been described either in patients with primary immunodeficiencies or in immunosuppressed patients with malignancies. These infections are listed in Table 391-1 according to the sites of gastrointestinal involvement and are discussed in more detail in Section 17. In addition to those listed, immunodeficient patients also are at increased risk for common bacterial and viral pathogens or infections with multiple organisms.

Cytomegalovirus, rotavirus, adenovirus, and herpes simplex virus are the most common viral agents. Cytomegalovirus is commonly identified in children with immunodeficiency and can cause inflammation or ulceration throughout the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including the pancreatobiliary system. Symptoms may include diarrhea, dysphagia, vomiting, abdominal pain, and GI bleeding. Histologic identification of cytomegalovirus within the intestinal tissue is required to establish a pathogenic role because cytomegalovirus commonly is excreted in the urine or stool of asymptomatic individuals. Rotavirus is a cause of vomiting and diarrhea in immunocompromised children and may disseminate into the liver parenchyma. In contrast, rotavirus rarely is a pathogen in normal or immunocompromised adults, most of whom have previously established immunity. Adenoviruses is reported to cause colitis in adults with AIDS and fulminant hepatitis in immunocompromised children. Diagnosis of adenovirus infection depends on histologic identification, which should be confirmed by culture.2 Herpes simplex virus usually causes oral and esophageal lesions and produces symptoms of dysphagia and odynophagia. Other viruses, such as astrovirus, picornavirus, and calicivirus, have been identified in the stool of HIV-infected adults with diarrhea, and they also may have a role in pediatric patients with diarrhea. In individuals without an identifiable pathogen, HIV itself may cause both esophagitis and enteritis with either dysphagia or diarrhea and malabsorption.

Table 391-1. Opportunistic Gastrointestinal Infections

Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, Escherichia coli, and Clostridium difficile are the most common bacterial infections in normal or immunocompromised hosts. In the presence of bowel dysmotility, overgrowth or normal bacterial flora in the small bowel can contribute to intestinal inflammation and malabsorption. In the immunocompromised host, infections such as Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter can be severe and prolonged, with a tendency to relapse and spread systemically. In a reported series of bacteremia in HIV-infected children, Salmonella was the second-most common bacterial isolate from blood. The common use of antibiotics in immunocompromised patients increases their risk of Clostridium difficile. Probiotic prophylaxis, sometimes presumed to be beneficial to prevent opportunistic infections, should probably not be used in the management of immunodeficient patients without further controlled studies, since an increased incidence of bacterial sepsis has been reported in this population.3 In developing countries, strains of enteropathogenic E coli are important causes of diarrhea in young HIV-infected children. In the United States, gastroenteritis caused by enteropathogenic E coli is rare, but it should be considered in patients with a recent history of travel.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, or M avium complex (MAC), accounts for the great majority of disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infections, involving bone marrow, liver, kidneys, and the GI tract. Approximately 12% of children with HIV infection have disseminated MAC. Although the rate of GI involvement by MAC is uncertain, 90% of children with disseminated MAC have GI symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, anorexia, and diarrhea. Hepatosplenomegaly is a common physical finding. Children with disseminated MAC often have very low CD4 T-cell counts and also have a poor prognosis, with a median survival period of 9 months. M tuberculosis also can infect the GI tract, usually the ileocecal region, and has been reported to cause peritonitis secondary to intestinal perforation.

Candida and Histoplasma are the most common fungal infections affecting immunodeficient children. Candida usually causes oral thrush and esophagitis (see Chapter 394). Fungal balls in the stomach can cause obstructive symptoms. Histoplasma has been reported to infect villi of the small intestine, resulting in abdominal pain and diarrhea. Both fungi can disseminate systemically.

Giardia is common in normal and immunocompromised children but often causes more severe diarrhea and abdominal pain and has a more protracted course in children with immunodeficiency. Cryptosporidium typically causes a chronic secretory diarrhea in immunocompromised patients, but the severity of the diarrhea may vary. Cryptosporidium also may colonize the biliary and pancreatic ducts and cause inflammation and obstruction. Isospora has been reported as a cause of diarrhea in immunodeficient adults, but it very rarely causes diarrhea in US children. Microsporidia are intracellular protozoan organisms that infect small intestinal epithelial cells. They are found in a significant number of HIV-infected adults with diarrhea but have yet to be reported in children.

Immune-Mediated Injury

Although infections are responsible for most cases of diarrhea, immunologic reactions also can play a significant role in gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Graft-versus-host disease and alloimmune reactions can occur in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency from either maternal-fetal transfusion or transfusion of nonirradiated blood products; graft-versus-host disease more commonly results from bone marrow transplantation in older children with hematologic malignancies. Clinical signs and symptoms include skin rash, hepatitis, diarrhea, GI bleeding, and eosinophilia. Rarely, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency results from chronic graft-versus-host disease. Autoimmune mechanisms, as suggested by the presence of antiepithelial cell antibodies, may be responsible for intestinal injury in some patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Autoimmune enter-opathy more commonly begins in infancy and presents with chronic diarrhea that frequently requires therapy with total parenteral nutrition. Immunologic reactions to food proteins, either cell-mediated or antibody (IgE)-mediated, also can cause eosinophilic intestinal inflammation and malabsorption. Eosinophilic inflammation may also be the result if immune dysregulation in the absence of allergic reactions. High titers of antigliadin and antimilk protein antibodies have been reported with HIV infection and other intestinal disease such as Crohn disease. The clinical relevance of these findings is unknown.

Medication-Induced Gastrointestinal Disorders

Medications used in the management of immunodeficiencies, whether congenital or acquired, frequently lead to nausea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. Mucosal injury, manifested by oral ulcers or diarrhea, can result from bone marrow suppression caused by agents such as methotrexate. Pancreatitis has been associated with such drugs as the reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (didanosine and lamivudine), antibiotics (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and pentamidine), and valproic acid. Elevated serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels, possibly caused by mitochondrial damage in the hepatocytes, have been reported in patients treated with the protease inhibitor ritonavir. Most children with immunodeficiency are receiving multiple medications, so the evaluation of potential causes of gastrointestinal symptoms should always include a careful review of potential medication side effects.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Primary immunodeficiencies likely affect as many as 1 in 2000 to 1 in 10,000 live births.4 A child with immunodeficiency can present with any one or a combination of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including diarrhea, growth failure, hepatosplenomegaly, GI bleeding, abdominal pain, emesis, and dysphagia. Of these symptoms, diarrhea probably is the most common. Suspicion of a possible immunodeficiency disorder is further suggested when these disorders are associated with abnormal skin/hair findings, cardiac disease (Williams syndrome), ectodermal dysplasia, severe food allergies/eczema, or recurrent oral thrush.

If a child with a known immunodeficiency presents with diarrhea, studies on the stool should include occult blood (hemoccult), culture (for Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, and C difficile), immunoassays for rotavirus Giardia antigen, and acid-fast stain or immunofluorescent stain for Cryptosporidium and Isospora belli. A complete blood count and blood culture should be obtained if there is fever. An elevated eosinophil count suggests a diagnosis of severe combined immunodeficiency, graft-versus-host reaction, or an allergic gastroenteritis. Testing for IgE antibody against a suspected food (eg, milk or soy protein) by a radioallergosorbent test (RAST) may be warranted. Following extensive evaluation, an identifiable cause of diarrhea can be found in 50% to 85% of patients. However, the vigor of investigation must be individualized and tempered because patients may have multiple infections, and many known infectious causes have no specific therapy. After treatable infections have been excluded, optimal management includes symptom relief and aggressive nutritional management to improve the overall quality of life.

In a child with known immunodeficiency presenting with abdominal pain and vomiting, a partial bowel obstruction, cholangitis, or pancreatitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Serum aminotransferase levels as well as amylase and lipase concentrations should be measured. Imaging studies such as an upright abdominal radiograph to look for evidence of intestinal obstruction and abdominal ultrasonography to detect biliary/pancreatic ductal dilatation or edema of the pancreas may be helpful. Radiographic evidence of intramural air in the small or large bowel (ie, pneumatosis) suggests either bacterial overgrowth or severe tissue necrosis.

Assessment of absorptive function includes testing of stool for reducing substance, pH, and fecal fat, as detailed in Chapter 408. A lactulose breath hydrogen test may help to diagnose small bowel bacterial overgrowth (see Chapter 408), but empiric therapy with metronidazole or other antibiotics is a reasonable option. Testing the stool for α1-antitrypsin may identify patients with protein-losing enteropathy. Serum protein, albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin levels are helpful in assessing the severity of protein malnutrition in a child with poor growth.

Fiberoptic endoscopy is indicated in evaluating patients with dysphagia unresponsive to empiric therapy for Candida; upper or lower gastrointestinal bleeding, or chronic diarrhea in whom no pathogen or cause has been found by other tests. Diagnosis of esophagitis caused by acid reflux, Candida, or cytomegalovirus can be made by esophageal biopsy. Pathogens that can be identified in biopsies of the small intestine and colon include Cryptosporidium, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, Histoplasma, Microsporidia, and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Both specific and supportive treatments are needed in treating a gastrointestinal disorder in a child with immunodeficiency. Specific therapy is directed at the cause of the disorder. If an infectious agent is found, appropriate therapy is initiated. Human immunoglobulin has been used in conjunction with ganciclovir to treat cytomegalovirus infection; oral human immunoglobulin has led to clearance of Cryptosporidium in 2 patients with immunodeficiency secondary to hematologic malignancies, but this therapy is not well proven.5 A somatostatin analog that reduces gastrointestinal secretion, octreotide, has been used with some success as a supportive therapy in patients with HIV infection and chronic diarrhea. Conditions that are caused by rotavirus, adenovirus, and Microsporidia have no known effective specific therapy. In these situations, optimizing nutritional status and controlling symptoms are of prime importance. The use of pharmacologic agents that decrease the gastric acidity should be limited in duration in the immunocompromised child to reduce the risk of bacterial or fungal overgrowth that is associated with the loss of the gastric acid barrier.6 For patients with bile duct obstruction associated with either pancreatitis or cholangitis, a biliary stent placed endoscopically can lead to significant symptomatic relief. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered when endoscopy is performed in patients with neutropenia or with an indwelling central venous catheter.

The approach to nutritional management depends on the degree of intestinal injury and malabsorption. Because most diarrhea illnesses in the immunocompromised host are prolonged, after correction of fluids and electrolytes, an “elemental” diet consisting of small peptides, glucose polymers, and medium-chain triglyceride is most easily absorbed.7 If tolerated, the diet can then be advanced to include more complex carbohydrates, long-chain fats, and intact proteins. Patients who are nauseous and anorectic may require placement of gastrostomy tube for feeding and administration of medications, whereas patients who have intractable diarrhea, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, or pancreatitis may require total parenteral nutrition. Prolonged placement of a nasogastric feeding tube in the immunocom-promised child should be avoided because it increases the risk for sinusitis. In patients who require total parental nutrition or have prolonged diarrhea or malnutrition, serum levels of micronutrients such as selenium, zinc, vitamins, and carnitine should be determined. Deficiencies of these micronutrients can potentiate immunodeficiency.

Several studies have demonstrated that megestrol acetate can stimulate appetite and improve weight for adults and children infected with HIV. However, the weight gain appears to be mostly in the form of body fat.8 Growth hormone, on the other hand, has been shown to maintain lean body mass in adults with AIDS, and pediatric trials show promise in decreasing protein catabolism in children with HIV/AIDS.9 It is remarkable, but not surprising, that since the advent of HAART (highly active anti-retroviral therapy) for patients with HIV infection, severe gastrointestinal complications such as intractable diarrhea and wasting seem to have diminished in frequency.10 Despite this progress, adolescents with HIV have lower growth parameters when compared to the general population, implying that gastrointestinal infections are not the sole cause of growth failure in children and adolescents with HIV.11 Combined antiretroviral therapies reduce mortality and morbidity from diarrhea in HIV-infected children who receive vitamin A supplements. Zinc supplements may also reduce frequency, duration, and severity of diarrhea in immunodeficient children.

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree