Gastroesophageal Reflux and Other Causes of Esophageal Inflammation

Colin D. Rudolph

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX

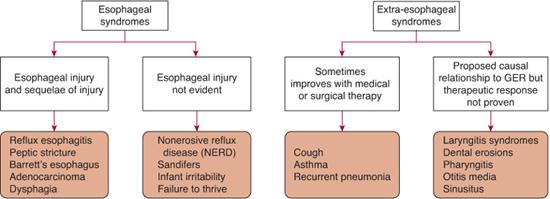

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the spontaneous passage of gastric contents into the esophagus. It is a normal physiologic process that occurs throughout the day in healthy infants, children, and adults. In infants, refluxed material often is expelled from the mouth, a benign process known as “spitting-up,” “spilling,” or “posseting.” Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) results from failure of the normal protective mechanisms that prevent damage to the aerodigestive tract following GER and is purported to manifest with a variety of symptoms and signs, shown in Figure 394-1. For almost all of these symptoms and signs, alternative etiologies must be considered prior to concluding that GERD is causative. This is particularly true in the infant and younger child because it is difficult to differentiate in young patients between GER and vomiting, and their symptoms are nonspecific.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Half of all infants between 0 and 3 months of age and two thirds of 4- to 6-month-old infants regurgitate at least once per day. The prevalence of regurgitation decreases dramatically after 8 months of age1,2 (eFig. 394.1  ). Typically, these infants are otherwise thriving and outgrow this problem by 18 to 24 months of age. Infants with GER are not at increased risk of ear, sinus, upper respiratory infections, or wheezing compared to a control population, but there may be a higher likelihood of feeding refusal than was found among the control infants.1 Gender, breast-feeding, and environmental tobacco smoke exposure are not significant factors related to infant regurgitation.2 In children between 3 to 9 years of age, symptoms of heartburn are reported in 2% to 5 %, epigastric pain in 7%, and regurgitation in 2% to 4 %.2,3,4 About 5% of adolescents report symptoms of heartburn, epigastric pain, or regurgitation.3 Follow-up studies of children and adolescents with GERD suggest that chronic symptoms may persist and require continued management through adulthood.4,5 Hiatal hernia (Fig. 394-2),6 obesity,7 and family history8,9 all may increase the risk of GERD. In a small number of infants and children, GER may cause chronic symptoms, but the true GER-related incidence for each of these is uncertain.

). Typically, these infants are otherwise thriving and outgrow this problem by 18 to 24 months of age. Infants with GER are not at increased risk of ear, sinus, upper respiratory infections, or wheezing compared to a control population, but there may be a higher likelihood of feeding refusal than was found among the control infants.1 Gender, breast-feeding, and environmental tobacco smoke exposure are not significant factors related to infant regurgitation.2 In children between 3 to 9 years of age, symptoms of heartburn are reported in 2% to 5 %, epigastric pain in 7%, and regurgitation in 2% to 4 %.2,3,4 About 5% of adolescents report symptoms of heartburn, epigastric pain, or regurgitation.3 Follow-up studies of children and adolescents with GERD suggest that chronic symptoms may persist and require continued management through adulthood.4,5 Hiatal hernia (Fig. 394-2),6 obesity,7 and family history8,9 all may increase the risk of GERD. In a small number of infants and children, GER may cause chronic symptoms, but the true GER-related incidence for each of these is uncertain.

A higher prevalence of GERD is observed in several special populations, including children with neuromotor impairment,10 repaired esophageal atresia or other congenital esophageal conditions,6,11-13 and those with chronic respiratory disease such as cystic fibrosis.13 Although pre-term infants often receive treatment for presumed GERD,14 the true incidence of GERD is clearly overestimated.15

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Most episodes of physiologic GER are confined to the distal esophagus, last less than 3 minutes, and cause no symptoms. GER occurs when transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), unaccompanied by swallowing, allow the escape of gastric contents into the esophagus.16 Less important causes of reflux include failure of the LES to adapt to sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure and chronically reduced resting LES pressure. Refluxed gastric contents are cleared by a combination of factors, including bulk clearance by gravity (when in an upright position) and peristalsis as well as neutralization of residual acid by the swallowing of alkaline saliva. Complications of GER ensue following failure of a variety of protective mechanisms (eTable 394.1  ). Prolonged exposure to acid is associated with a higher risk of esophagitis, but extraesophageal complications of GER may occur despite esophageal acid exposure being in the normal range. When the esophagus is filled following gastroesophageal reflux, the upper esophageal sphincter opens and the airway closes, allowing the gastric refluxate to pass into the pharynx without being aspirated into the airway. Stimulation of esophageal or pharyngeal afferents may induce brief apnea, cough, or vomiting. Following an episode of pharyngeal reflux, the material is cleared from the pharynx by either vomiting or swallowing, and breathing resumes. Abnormalities of these airway protective mechanisms will potentially result in airway symptoms from inadvertent exposure of the larynx and airway to caustic materials.

). Prolonged exposure to acid is associated with a higher risk of esophagitis, but extraesophageal complications of GER may occur despite esophageal acid exposure being in the normal range. When the esophagus is filled following gastroesophageal reflux, the upper esophageal sphincter opens and the airway closes, allowing the gastric refluxate to pass into the pharynx without being aspirated into the airway. Stimulation of esophageal or pharyngeal afferents may induce brief apnea, cough, or vomiting. Following an episode of pharyngeal reflux, the material is cleared from the pharynx by either vomiting or swallowing, and breathing resumes. Abnormalities of these airway protective mechanisms will potentially result in airway symptoms from inadvertent exposure of the larynx and airway to caustic materials.

FIGURE 394-1. Classification schema for gastroesophageal reflux disease.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a normal physiologic event; therefore, the key to evaluation and diagnosis is to determine when GER is the cause of disease. Diagnostic approaches vary depending on the presenting symptom, and in all cases, other treatable causes of the disorder must be considered during the diagnostic evaluation.17 No test serves as the gold standard for making a diagnosis of GERD. Rather, a series of tests is often required to determine if a particular disorder is being caused by GER.

Upper Gastrointestinal Radiography (UGI) This test is often included in the evaluation of the vomiting infant. It is useful to diagnose anatomic abnormalities that present with nonbilious vomiting as with GER, such as esophageal stricture, pyloric stenosis, antral webs, or disorders of esophageal motility such as achalasia. The UGI is not useful for diagnosis of GER because reflux of ingested radiographic contrast often occurs in healthy individuals.

Esophageal pH Monitoring and Impedance Monitoring This test utilizes a pH sensor with or without a series of sensors that measure electrical impedance. This allows evaluation of the number and duration of acid and nonacid reflux episodes into the lower and/or upper esophagus. Prolonged esophageal mucosal exposure increases the risk for esophagitis. Measurement of 24-hour esophageal acid exposure should not be used as the sole determinant of whether GER is responsible for airway symptoms such as apnea, recurrent pneumonia, wheezing, or hoarseness. Esophageal pH and impedance monitoring should be combined with a pneumogram that measures oxygen saturation and chest wall and airflow movements. If one is attempting to establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship between apnea episodes and GER, however, these time-consuming and technically challenging tests often fail to clarify if apnea is caused by GER. If esophageal pH monitoring is abnormal, there is a somewhat higher probability that GER is a contributing factor causing airway symptoms such as recurrent wheezing or pneumonia, but a normal study does not exclude GER as a potential factor, and an abnormal study does not prove a causative relationship.

FIGURE 394-2. Endoscopic photograph of hiatal hernia. (Source: Reprinted with permission from Gastrolab, Vasa, Finland: http://www.gastrolab.net.)

Upper Endoscopy with Biopsy of the Esophagus This test is useful to evaluate if there is esophagitis or other sequelae of chronic esophageal acid exposure such as stricture or Barrett esophagus. In addition, it allows diagnosis of other disorders, such as Crohn disease and eosinophilic or infectious esophagitis.

Nuclear Scintigraphy This test evaluates the distribution of isotope-labeled formula or food following normal feeding. Episodes of GER are monitored for up to an hour after feeding. Because GER may occur in normal individuals, documentation of these episodes is of little pathophysiologic use unless aspiration into the lungs is detected. If this occurs, it is a clear indication that airway protective mechanisms are deficient.

Other Diagostic Approaches Other tests may be utilized to evaluate children with airway symptoms. These include chest radiographs or computed tomography scans, laryngoscopy, and bronchoscopy with alveolar lavage for pepsin and/or lipid-laden macrophages. Often, empiric therapy may be administered on the basis of history, but a treatment response does not necessarily confirm a diagnosis of GERD, since other acid-related disorders or a placebo response may also result from treatment.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The approach to the evaluation and management of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) varies depending on the symptoms presenting with possible GERD. GER is a normal physiologic event, and the evaluation is therefore directed toward determining if GER is either causing or contributing to a specific symptom or sign.

Uncomplicated Reflux

A thorough history and physical examination is generally sufficient to arrive at a diagnosis of uncomplicated GER, which obviates the need for any diagnostic testing. Other potential causes of vomiting should be considered in an infant with warning signs (Table 394-1) such as forceful or bilious vomiting, abdominal tenderness or distension, gastrointestinal bleeding, diarrhea, constipation, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, a bulging fontanelle, macrocephaly or microcephaly, seizures, or an onset of vomiting after age 6 months. Infants with complications purported to be due to GER, such as weight loss, excessive irritability because of esophageal pain, feeding difficulties, apneic episodes, recurrent stridor, or pneumonia, require different management approaches.

Table 394-1. Warning Signs in the Vomiting Infant

Gastrointestinal bleeding: hematemesis, hematochezia |

Consistently forceful or bilious vomiting |

Consistent vomiting after 6 months of life |

Abdominal tenderness, distention |

Neurologic signs: bulging fontanel, macro/microcephaly, seizures, focal findings |

Protracted diarrhea |

Constipation |

Fever |

Lethargy |

Hepatosplenomegaly |

Faltering growth/failure to thrive |

Recurring Vomiting and Poor Weight Gain

The infant with recurrent vomiting and poor weight gain presents a more challenging problem. Other potential causes of poor weight gain need to be considered as outlined in Chapters 29 and 30. Often, inadequate calories are offered to the infant as parents attempt to reduce the frequency or volume of vomiting. In these situations, parental education is usually sufficient to resume weight gain. If appropriate calories are consumed but vomiting is severe enough to limit weight gain, thickening of the formula or increasing the caloric density of the formula is useful. No widely available prokinetic agent has been shown to be useful. Rarely, supplemental nasogastric feeding or jejunal feeding may be required to achieve weight gain. The severity of GER usually gradually decreases, and the infant can resume a more normal eating pattern by 3 to 6 months of age. Surgical therapy is almost never required to achieve good weight gain. If it is contemplated, a pediatric gastroenterologist should be consulted to consider other potential causes of vomiting.

Esophagitis

Esophagitis may be caused by GER, presenting with symptoms including hematemesis, anemia, and atypical seizurelike movements with torsion of the neck known as Sandifer syndrome. Symptoms of excessive irritability and feeding refusal are purported to be due to GERD, but no studies demonstrate improvement of these symptoms following GERD treatment in infants.18 However, adults with esophageal pain and dysphagia improve following pharmacologic treatment.19 The approach to the infant with feeding refusal is discussed in Chapter 31 and to the infant with excessive crying in Chapter 83. The differential diagnostic approach to gastrointestinal bleeding is reviewed in Chapter 387. In the older child, esophagitis may present with complaints of substernal or chest pain. In the older child with heartburn, an empiric trial of antisecretory therapy is generally the most reasonable initial approach to therapy. If symptoms resolve, therapy can be continued for 3 to 4 months, and further evaluation is required only if symptoms recur at the cessation of therapy. Definitive diagnosis of esophagitis requires that visible breaks in the esophageal mucosa are observed with endoscopy (Fig. 394-3). Esophageal biopsy is necessary to differentiate between other potential causes of esophagitis, such as infectious etiologies or eosinophilic esophagitis. Treatment of GER-induced esophagitis should focus on reducing the acid exposure of the esophagus with adequate doses of antisecretory agents; generally, a proton pump inhibitors is used and provides effective treatment.20-24 Severe, prolonged erosive esophagitis can result in the development of either peptic strictures or a Barrett esophagus (eFig. 394.2  ). Peptic strictures can be dilated, and recurrence can be prevented with either long-term, aggressive medical therapy with a proton pump inhibitor or antireflux surgery. Barrett esophagus presents with intestinal metaplasia in the distal esophagus.25 It is thought to represent a premalignant lesion, with evolution to esophageal adenocarcinoma over many years. There is no definitive treatment, but vigorous medical therapy or antireflux surgery is usually recommended. Because of the long-term risk of adenocarcinoma, children with this diagnosis should undergo surveillance esophagoscopy and biopsy every 3 to 5 years.26

). Peptic strictures can be dilated, and recurrence can be prevented with either long-term, aggressive medical therapy with a proton pump inhibitor or antireflux surgery. Barrett esophagus presents with intestinal metaplasia in the distal esophagus.25 It is thought to represent a premalignant lesion, with evolution to esophageal adenocarcinoma over many years. There is no definitive treatment, but vigorous medical therapy or antireflux surgery is usually recommended. Because of the long-term risk of adenocarcinoma, children with this diagnosis should undergo surveillance esophagoscopy and biopsy every 3 to 5 years.26

Nonerosive Reflux Disease

Nonerosive reflux disease exhibits typical symptoms of GERD but normal esophagoscopy in children and adolescents.27 These patients rarely progress to actual erosive esophageal disease, but symptoms may be troubling. Diagnosis of this disorder in infants and younger children is challenging because symptom reporting is inaccurate and lacks specificity. Symptoms of irritability have previously been used as an indication of GERD, but placebo-controlled trials demonstrate a lack treatment efficacy.18 Therefore, definitive diagnosis requires documentation of symptom correlation with GER episodes by pH probe and/or esophageal impedance.

Acute Life-Threatening Events

Acute life-threatening events have been associated with GER in infants but may be caused by other disorder, as described in Chapter 119. Episodes associated with GER typically are obstructive in nature and occur while the patient is awake, supine, and within 1 hour of a feeding.28 Central apnea has not been clearly associated with GER, and apneic episodes in premature infants15 have not been shown to be improve with GER therapy. Diagnosis is generally best made from the typical history. Episodes occur infrequently, so even carefully performed combined 24-hour esophageal pH and monitoring combined with measurements of air flow and chest wall impedance may be unable to document episodes. Therapeutic options include thickened feedings and acid-suppressant therapy. Position therapy with prone positioning after meals can be considered, but generally the fear of an increased potential of sudden infant death syndrome in an infant with previous acute life-threatening events limits the advisability of this approach. Antireflux surgery is effective, but because the episodes are self-resolving and decrease in frequency after age 6 months in most infants, surgery is very rarely indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree