Birth plans

Birth plans initially were developed by natural childbirth advocates in the 1980s as a response to pregnant women’s sense of loss of agency in the birth process. As part of a larger movement for women’s rights and patients’ rights, the natural birth movement sought to renormalize birth and give women control over their own pregnancies and birth processes, pushing back against unwanted and unwarranted medical interventions. However, this movement also had an antiscientific cast and was, in many ways, unnecessarily antagonistic toward medical intervention.

Birth plans remain popular, with many women concerned about avoiding unnecessary interventions and wanting to exercise their informed consent. Birth plans are also recommended by several popular pregnancy books and websites, most of which offer some form of birth plan template. Natural birth organizations and teachers also offer birth plan information, which tend to be oriented toward avoiding medical interventions. Many of these birth plan templates appear in the form of checklists of choices regarding interventions, with little guidance about why one would choose to have or avoid them or which interventions preclude the choice of other interventions (eg, continuous internal fetal monitoring while walking during labor). The checklist forms also frequently include both trivial and outdated considerations that do not reflect current practices or significant choices in care, such as preferences around enemas, music, or lighting. Many hospitals now also offer checklist-style birth plans that reflect current practices and options that are available at that facility, but they are likewise limited in utility because they do not include some significant choices or a sense of which options preclude or give rise to other options.

The use of birth plans has also not had the intended effects of facilitating constructive communication between pregnant patients and their providers or providing better informed consent for laboring women. Staff members sometimes feel hostile toward women who have birth plans, and distrust can build on both sides. Some women believe that their values and choices are not respected, and providers frequently believe that women come in with birth plans that are uninformed and unrealistic. One study found that “patients’ birth plans usually provoked some degree of annoyance. This was mainly because the requests were sometimes believed to be inappropriate.” Additionally, “ineffective, authoritarian, paternalistic communication” patterns are sometimes reported by patients in obstetrics. One popular obstetrician blogger described women who develop birth plans as having “tantrums” filled with “ultimatums” given “to defy authority.” In 1 study, 65% of medical staff members falsely believed that women with birth plans had worse obstetric outcomes than women who did not have birth plans. Another study found that some providers believed that time constraints warranted making decisions for women instead of going “through the lengthy process of dialogue and negotiation to find a way to respect the women’s wishes.” Rather, women who develop birth plans usually are seeking to exercise the same right to informed consent regarding medical interventions that all competent adult patients have.

In most cases, women who make birth plans desire to have their experiences of birth reflect their values and to exert reasonable control over what happens to their bodies. Unfortunately, they often receive poor (or no) guidance regarding how to have their values reflected in their care choices. Women may have heard or experienced horror stories about providers who ignored their patients’ choices or threatened that “you or your baby could die” if they refused routine interventions. They are sometimes influenced by natural birth advocates who paint overly rosy pictures of potential pain and complications that arise in birth. And sometimes, providers may push interventions as defensive medicine to avoid any possibility of lawsuits, even if those interventions are not strictly necessary.

Toward the birth partnership

Moving beyond unidirectional birth plans toward the development of a birth partnership can build trust and facilitate constructive 2-way communication and shared decision-making between patient and obstetric care provider. Birth partnerships differ from birth plans in several key ways.

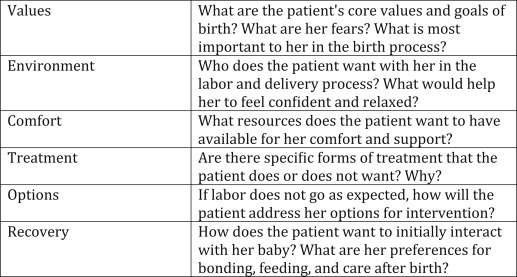

Birth partnerships involve ongoing conversation, before and during the birth process. Early on in the pregnancy, providers should discuss their own philosophies and practices of birth and provide educational materials to the patients to begin dialogue around decision-making and expectations. This can allow both patients and providers to assess early on whether the relationship is a good “fit” based on the underlying values and priorities of each party. This also can allow patients to express their values and goals of care in the birth process, including anything that might be out of the ordinary within the provider’s experience. Over the course of the pregnancy, providers can use discussion tools, such as the VECTOR (values, environment, comfort, treatment, options, recovery) tool ( Figure ) to develop ongoing conversations around patient values and preferences.

Some providers have found that planning for an extended visit at approximately 34–36 weeks gestation is helpful in discussing the woman’s values and preferences in the birth process. This allows the provider to provide appropriate education to the patient regarding what choices are realistic, are available in concert with one another, and may be medically advised in her unique situation. It also allows the provider to listen to what the patient cares about in the birth process. What matters most to her? What are her fears? What are her expectations? The extended educational visit offers an opportunity to learn about what she values, what she knows, and what she does not know and to offer guidance as she approaches labor and delivery. This ongoing conversation should also include labor itself and the changes that happen and the decisions that must be made over the course of labor.

The basic ethical principle of informed consent applies to pregnant and laboring women just as it does to any other competent adult patient, so women retain the right to refuse particular interventions in labor. But there is a great deal that obstetric care providers can do to avoid intractable conflicts proactively, especially for higher-risk patients who are more likely to need interventions. Patients must be reasonably informed about treatment options, and they often rely on a variety of sources to inform themselves. Providers should offer information proactively from high-quality, evidence-based sources to best inform their patients and lead them away from low-quality, inappropriate sources. Women often arrive with information from natural birth advocates, pregnancy books and websites, stories from friends and family, and their own encounters with the healthcare system. Some of these may be helpful, although others may not be, and each woman comes into the birth process with her own values, hopes, and fears. Providing appropriate information and conversation work to build trust so that, when a provider recommends a particular intervention and gives an appropriate reason for the intervention, the relationship stands on solid ground and that patient becomes more likely to accept the intervention or to give a good reason for declining.

Obstetric care providers can best build their patients’ trust by being trustworthy and respectful in their encounters with patients. Even difficult patients and those who are inclined to distrust medical professionals are best encountered with discussion, rather than dismissiveness. They may have come into the encounter with experiences of being harmed, dismissed, or disrespected by providers; ignoring their concerns can magnify this negative perception. These patients may have values that they want to uphold that may not be shared by the provider, such as having a large family or avoiding blood transfusions, but should be respected nonetheless. Providers do not need to offer treatments that are not medically beneficial or that they do not believe are in the patient’s best interest, but “it is not ethically justifiable to evoke conscience as a justification to coerce a patient into accepting care that she does not desire.” One study found that “the great majority of mothers who had experienced episiotomy (73%) stated that they had not had a choice in this decision.” In many cases, especially for primigravid women, they may have received bad advice or heard horror stories from other mothers, and respectful communication will be productive in mitigating their fears.

Interventions should not be offered primarily as a matter of provider convenience, and obstetric care providers should be up to date regarding current guidelines, including diagnoses of stalled labor, macrosomia, and other common reasons for intervention. For women who are candidates for a trial of labor after cesarean delivery, every effort should be made to make this available to them if they are interested, with appropriate communication about what constitutes an appropriate trial and course of action, should the trial not proceed well. Likewise, women who would like to avoid the use of medication for pain control should not be pressured into using medication, but neither should they have such medication withheld if they change their minds during labor. Providers can uphold those choices respectfully and can communicate with patients regarding the reason that they might want or not want medication for pain control and help them avoid feelings of failure if they do choose to use it, including a discussion of how the experience of pain in labor differs from woman to woman and how the use of pain medication in birth is safe and effective. Patient choices around early bonding, feeding, the presence of family, and rooming-in can be upheld in a variety of circumstances, and accommodations should be made to enhance a family’s first days together.

Effective birth partnerships begin at the start of the provider-patient relationship and can take into account the wide variety of experiences and expectations that different patients bring to that relationship. When care providers work consistently to earn their patients’ trust from the beginning and routinely talk with patients about their desires, hopes, and fears in pregnancy, birth, and parenting, they are more likely to work with patients in ways that enhance both objective outcomes and satisfaction for both provider and patient.

When effective communication is used by all physicians in a practice, patients learn that they will be treated with respect regardless of who is on call when they go into labor. Communication breakdowns may occur when women encounter unfamiliar providers, so it is important that any out-of-the-ordinary information be shared quickly and effectively with the on-call provider so that women in labor do not believe that they have to start over in advocating for themselves and their choices. As the birth partnership develops, if the primary provider is not expected to be attending the birth, the provider and patient should work together to develop a short list of key preferences and expectations that the patient has that may differ from the standard protocols that are used by that provider group, which should be shared with the medical team as labor begins. Provider groups also need to develop communication among their teams as patients express unusual choices before delivery so that all of the members of the team may be informed and not surprised by the request once the laboring woman presents at the hospital or birth center. For example, if a woman expresses a religious need for female-only staff or no blood transfusions under any circumstances, these should be identified and shared proactively to ensure that they are respected at the time of labor and delivery. Where there are significant differences in birth philosophy and practices among providers within a group that may be relevant to particular patients, the patients should be made aware of these differences and the rationale behind them as they arise so that both patient and provider can determine a course of action, including the option of a change of provider.

Birth plans were developed as a tool for women to use to communicate their desires, goals, and choices in the birth process, but they often do not function effectively, because they can reflect inconsistent, outdated, or trivial choices. They can alienate medical staff and lead to breakdowns in communication instead of enhancement. A better alternative, the birth partnership, can build trust and effective communication between patient and provider through a process of mutual education. Obstetric care providers who are willing to talk with their patients, to educate them on what options are available and consistent with each other, and to take the time to listen to the patient’s values and concerns can practice effective prevention of many of the conflicts that arise.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree