Foreign-Body Aspiration

Margaret A. Kenna

EPIDEMIOLOGY

According to the National Safety Council, choking was the fourth leading cause of unintentional injury-related death in the United States in 2000, and the leading cause of death for children under age 12 months. In the same year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 160 children under age 14 years died from inhaled or ingested foreign bodies. Of the objects that caused death, 41% were food items and 59% were nonfood. Although children of all ages are at risk, most (75–90%) documented aspirations of foreign bodies by children involve preschoolers. The approximate distribution by age is under 1 year is 10% to 15%; 1 to 2 years 40% to 50%; 2 to 3 years 15% to 25%; and over 3 years 15% to 20%. Statistics show that boys aspirate foreign bodies more often (2:1) than girls. Fortunately, most choking episodes are nonfatal. They are common, however, an estimated 17,537 children younger than 14 years were treated in US emergency departments (ED) for choking episodes in 2001. Sixty percent of nonfatal choking episodes were associated with food items, whereas 31% were nonfood. Coins were involved in 18% of all choking-related ED visits for children ages 1 to 4 years.1

During their orally focused phase of development, infants and younger children are likely to place anything, both edible and inedible, into their mouths. Choking and aspiration may occur because they have not yet developed molar teeth; the coordination of the mechanisms for swallowing and airway protection are not fully mature; the object is inedible in the first place, or they are trying to climb and run at the same time as they are chewing. Adolescents most often aspirate nonfood items; they may absent-mindedly chew on objects such as pen caps, or hold items that are in use, like head scarf pins, in their mouths. Large case studies indicate that nuts, peanuts, raw carrots, apple slices, and beans account for over half of all foreign-body aspirations by children. Toys and toy parts, and other small objects such as Velcro diaper tabs and button batteries, make up the rest. One report of 103 asphyxiation deaths of young children by food identified hot dogs (17%) as the single most common aspirated food, followed by candy, peanuts, nuts, and grapes.

Although foreign bodies in the larynx and tracheobronchial tree are most likely to cause airway obstruction, occasionally an esophageal foreign body will also result in airway obstruction (see Chapter 395). Therefore, if the patient develops symptoms of airway obstruction after swallowing a foreign object, a diagnostic workup that may include radiographic evaluation and endos-copy are still required for management and removal. It is also possible for a patient to cough up, and subsequently swallow, a foreign body from the larynx or tracheobronchial tree; conversely, a patient may regurgitate a foreign object or piece of food from the esophagus into the airway. Finally, foreign bodies may lodge in the nasopharynx, either primarily or as a result of being inhaled, coughed, vomited up, or occasionally lodged there through the nose. It is reasonable to inspect these other anatomic areas in the operating room if the foreign body is not found in the tracheobronchial tree or if the history or radiographic evidence suggests that it might be lodged in one of these other locations.2-4

PATHOGENESIS

When a foreign body enters the posterior pharynx, discomfort and irritation cause the child to cough or cry. The initial phase of this response is a vigorous inspiration that causes foreign-body aspiration and subsequent impaction within the airway. This impaction can occur anywhere from the level of the oropharynx or hypopharynx distally. In the confined space of the airway, the foreign body increases resistance to inspiratory and expiratory flow. Because it can create a valve-like effect, a foreign body trapped in the intrathoracic airways can cause more airflow obstruction during expiration than inspiration and can produce generalized or asymmetric gas trapping (one of the signs of foreign-body impaction in a bronchus). As surface sensory receptors of the respiratory mucosa become stimulated, they initiate a strong reflex cough. This can last for as long as several minutes to a half hour. If the foreign body fails to move within the airway, then the mucosal receptors will become adapted to the prolonged pressure caused by the lodged foreign body so that the initial coughing will often subside. Coughing will not recur until other sensory receptors are stimulated, either by movement of the foreign body or by secretions. Thus, a latent period free of symptoms may occur and last from hours to months or even longer.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

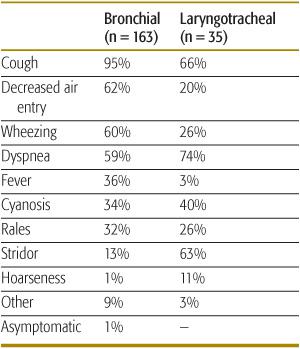

Aspiration of a foreign body can cause a variety of respiratory signs, although cough is the most common (Table 118-1). The manifestations are determined by many factors, including the size, shape, composition, and location of the aspirated material, as well as the time elapsed since the aspiration. Symptoms may change over time if the foreign body moves or swells up (common for vegetable materials such as peas and beans). The acute event is frequently marked by a sudden onset of choking or coughing and often followed by wheezing, dyspnea, stridor, and possibly hoarseness. Symptoms and signs are somewhat different, depending on whether the aspirated foreign body has lodged in a bronchus (most common) or in the larynx or trachea (Table 118-2). Objects lodged in the larynx may cause hoarseness or aphonia. If the foreign body has been present for several days or longer, fever may result from trapped secretions with resulting inflammation. If the foreign body is lodged below the carina, then auscultation may reveal decreased air entry on one side. This will frequently be associated with localized gas trapping initially and with alveolar collapse later. Wheezing and asymmetric breath sounds are more common if the foreign body is in a bronchus, while stridor and hoarseness are more often associated with laryngeal or tracheal foreign bodies. Even if the foreign body aspiration is not observed, a history of sudden onset of choking, coughing, dyspnea, and stridor; or otherwise unexplained chronic cough, wheezing, or recurrent or chronic pneumonia, should signal the possibility of foreign-body aspiration. Finally, unexplained hemoptysis may result from laceration of the airway and, over time, from formation of friable granulation tissue.

Table 118-1. Signs and Symptoms Associated with Impacted Foreign Bodies

The diagnosis of foreign-body aspiration is frequently delayed. As many as 15% to 20% of cases of foreign-body aspiration are diagnosed more than 1 month after the event. A similar proportion of children with subsequently retrieved airway foreign bodies have been reported to be completely free of clinical symptoms and radiologic signs when first examined by a physician. Delay may be due to lack of a suspicious history, minimal symptoms, incorrect diagnosis (wheezing treated as asthma rather than a foreign body), or limited access to appropriate health services.5

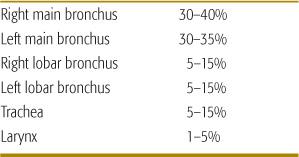

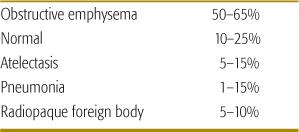

Although many aspirated foreign bodies are radiolucent, including much of the vegetable matter and many plastic toys, posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs, anterior posterior, and lateral soft tissue films of the neck are useful initial diagnostic methods (Table 118-3). For bronchial foreign bodies, the most commonly demonstrated abnormality on chest radiograph is obstructive asymmetric hyperinflation, which is present in up to 65% of the cases. Inspiratory and expiratory or decubitus films have long been recommended. However, these studies can be difficult to obtain and their diagnostic predictive value is only modest. Ten to 25% of children with subsequently documented airway foreign bodies (up to 60% of those in a laryngotracheal location) will demonstrate no abnormality on plain-chest radiographs. Other diagnostic techniques, including fluoroscopy, spiral and three-dimensional computed tomography of the chest, and virtual bronchoscopy, have been utilized as supplemental tools, especially in the diagnosis of radiolucent foreign bodies, or if the history of aspiration is confusing or absent. However, if the history or physical examination strongly suggests foreign-body aspiration, even if the radiographic evidence is negative or equivocal, diagnostic endoscopy should be undertaken.6

Table 118-2. Location of Impacted Foreign Bodies

MANAGEMENT

Table 118-3. Radiographic Findings Associated with Impacted Foreign Bodies

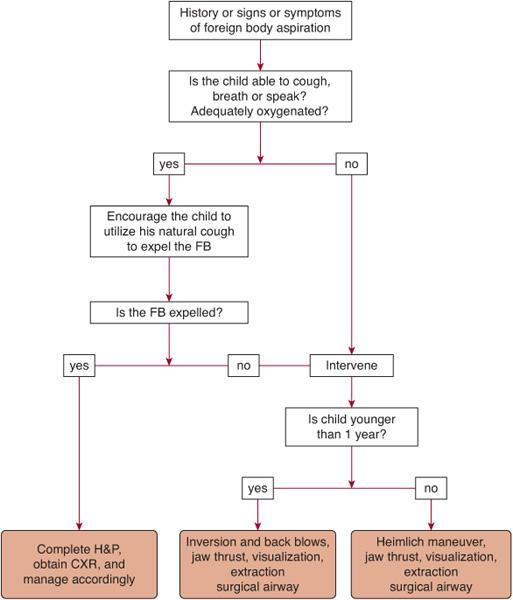

The management of foreign-body aspiration (Fig. 118-1) varies according to presentation of the disorder and age of the patient. If the child presents with acute signs and symptoms of airway obstruction due to foreign-body aspiration but is conscious and can cough, breathe, or speak, then the child should proceed to the hospital for foreign-body removal. However, if the child appears to have complete obstruction of the airway, and becomes unconscious and cyanotic, then the rescuer should intervene. Blind finger sweeps are to be avoided in infants and children because the foreign body could be pushed back into the airway, causing further obstruction. If the foreign body can be visualized, it should be manually removed, using Magill or other large forceps if available. When initial interventions fail, a jaw thrust should be performed, with the hope of partially relieving the obstruction. In the unconscious, non-breathing child, a tongue-jaw lift can be performed by grasping both the tongue and lower jaw between the thumb and finger and lifting. If these maneuvers fail, and based on current American Heart Association recommendations, the most appropriate intervention for infants under the age of 1 year consists of holding the infant face down along the rescuer’s arm and delivering a series of sharp back blows between the shoulder blades. For children over the age of 1 year, the Heimlich maneuver (subdiaphragmatic abdominal thrusts) should be the first mode of intervention. If all of these methods of reestablishment of adequate air exchange fail, and the child remains cyanotic, unconscious, and obstructed and is not ventilating adequately, an attempt to establish a surgical airway, such as a tracheotomy or cricothyroidotomy distal to the suspected site of obstruction, should be considered. Although the performance of both tracheotomy and cricothyroidotomy can be technically challenging, cricothyroidotomy may be even more difficult than tracheotomy due to the performance of the technique through a very small opening and the marked mobility of the laryngeal, tracheal, and esophageal structures in young children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree