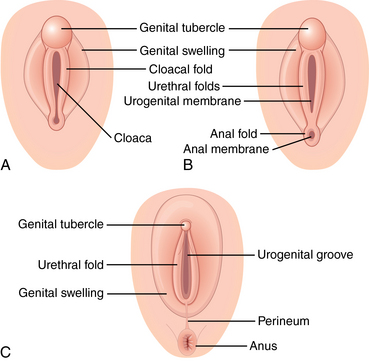

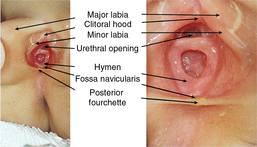

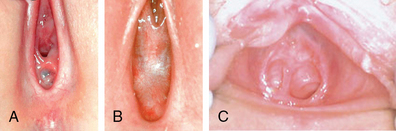

CHAPTER 17 The female genital examination is a recommended yet an under-performed part of the routine physical for pediatric and adolescent girls. Routine performance of the female genital exam allows the health care provider to build skills and familiarity with normal variants in the genitourinary system, and establish a baseline from which to monitor individual development and provide information and reassurance to children, youth, and parents or caregivers. Many health care providers, however, are underprepared to recognize normal genital findings in the prepubescent girl and are unfamiliar with common variations.1 At 5 to 6 weeks of gestation, fetal gonads are bipotential, capable of differentiating into either a testis or an ovary. Both male and female embryos have one pair of primary sex organs, or gonads, and two pairs of ducts, wolffian ducts and müllerian ducts. During the sixth week, the primordial germ cells migrate into the primary sex cords and begin to differentiate. Leydig and Sertoli cells appear in male embryos, producing testosterone and antimüllerian hormone. In female embryos, the gonads do not produce testosterone, and the gonads develop into ovaries. The wolffian ducts deteriorate, and the müllerian ducts develop into the uterus, upper vaginal tract, and fallopian tubes. The external genitalia differentiate at between 8 and 12 weeks of gestation (Figure 17-1). Active mitosis continues and thousands of germ cells, oocytes, are produced. A newborn female may have 2 million primary oocytes at birth. However, after birth, no further oogonia occurs. FIGURE 17-1 Development of the external genitalia. A, Early development before completion of the urorectal septum. B, Separation of the anus from the urogenital sinus lined by the urethral folds. C, Development of the genital swelling. (From Crum C, Nucci M, Lee K: Diagnostic gynecologic and obstetric pathology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.) In preterm neonates, the labia majora may not cover the labia minora, and the clitoris will be prominent. Term newborns will have enlarged labia majora, which usually cover other external structures, a relatively large clitoris, and labia minora with dull pink epithelium, because of maternal estrogen effects (Figure 17-2). A creamy white or slightly blood-tinged discharge is normal for up to 10 days after birth. The hymen is relatively thicker, pink-white, and redundant and may remain so up until 2 to 4 years of age (Figure 17-3). FIGURE 17-2 Newborn with estrogen effect. (From Zitelli BJ, Davis HW: Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, ed 4, St. Louis, 2002, Mosby. Courtesy Ian Holzman, MD, Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY.) FIGURE 17-3 External genitalia of the prepubertal child. (From Baren J, Rothrock S, Brennan J, et al: Pediatric emergency medicine, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.) Disorders of sexual differentiation (DSD) have their genesis in early fetal development and result from developmental variations in one or more of the three components of sex determination and differentiation: chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, and/or phenotypic sex. Manifestations of some types of DSD are evident at birth in the newborn with ambiguous genitalia2; other types may only become evident in early adolescence with variations in secondary sexual development (see Chapter 15 for further discussion). In the absence of congenital anomalies, all female infants are born with a hymen, which can present in a variety of configurations. Commonly, the hymen is fimbriated, annular, or crescentic (Figure 17-4). Annular hymens are more common at birth, whereas crescentic hymens are more common in girls over 3 years of age. Figure 17-5 illustrates hymen types that are rare—septate, cribriform, and imperforate. Table 17-1 presents congenital anomalies in development of the female genitalia. TABLE 17-1 Congenital Anomalies in the Development of Female Genitalia FIGURE 17-4 Variations in normal hymens. A, Crescentic. B, Annular. C, Fimbriated. D, Redundant. (From McCann JJ, Kerns DL: The anatomy of child and adolescent sexual abuse: a CD-ROM atlas/reference, St. Louis, 1999, Intercorp Inc.) FIGURE 17-5 Abnormal hymens. A, Cribriform. B, Imperforate. C, Septate. (A and B from McCann JJ, Kerns DL: The anatomy of child and adolescent sexual abuse: a CD-ROM atlas/reference, St. Louis, 1999, Intercorp Inc; C from Lahoti SL, McClain N, Girardet R et al: Evaluating the child for sexual abuse, Am Fam Physician 63[5]:883-892, 2001.) After the newborn period and before menarche, the clitoris is about 3 mm in length and 3 mm in transverse diameter. Hymens in prepubertal girls are thinner, redder, and more sensitive to touch. With the onset of puberty, the hymen often shows an estrogen effect that makes it pinker and more redundant before the other secondary sexual characteristics appear. The prepubertal vagina is rigid, nonelastic, and thin-walled, lined by columnar epithelium, which normally appears redder than the squamous epithelium lining the vagina of pubertal adolescents and adult women. Adrenarche, the development of pubic and axillary hair, occurs at approximately the same time as thelarche, the development of the breast. The mean age of adrenarche in girls is 9 to 10 years of age, but may occur as early as 7 to 8 years of age, particularly in African-American girls (Figure 17-6). Table 17-2 correlates development and sexual maturity rating (SMR), also known as Tanner stages, which includes breast development and pubic hair distribution in girls. The external genitalia and internal structures—labia majora, labia minora, hymen, vagina, ovaries, uterus—are developing under the influence of increasing estrogens, but they are not included as part of the SMR. Table 17-3 presents pubertal changes of the vagina. TABLE 17-2 *Not part of classic SMR, but important to note in exam findings and for anticipatory guidance. Data from Neinstein LS et al editors: Adolescent health care: a practical guide, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Jenny C: Sexually transmitted diseases and child abuse, Pediatr Ann 21(8):497-503, 1992; Emans SJ and Laufer, MR, editors: Pediatric and adolescent gynecology, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2012, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. TABLE 17-3 Pubertal Changes of the Vagina Data from Jenny C: Sexually transmitted diseases and child abuse, Pediatr Ann 21(8):497-503, 1992. Female circumcision, or female genital mutilation, is prevalent in many parts of the world, particularly sub-Saharan Africa and some Asian countries, and is considered a rite of passage and a prerequisite for marriage in some cultures.3 The procedure is not legal in the United States or Canada, but immigrant girls and adolescents may have had the procedure performed previously in their country of origin.4 Complications include infection, hemorrhage, tetanus, difficulty in urination, sexual dysfunction, and infertility.5 There is evidence the acceptability of female genital mutilation decreases over time in immigrant communities. The Information Gathering table reviews information gathering on preadolescent and adolescent menstrual history and adolescent sexual history. For approach to adolescent information gathering and obtaining sensitive health information, see Chapter 4. Information Gathering for Female Genitalia at Key Developmental Stages Most young children can be examined in the frog-leg position: supine, with knees apart and feet touching in the midline (Figure 17-7). For an apprehensive young child, the parent or caretaker can sit in a chair or on the examination table in a semireclined position (feet in or out of stirrups) with the child’s legs straddling her thighs. Older children can be placed in adjustable stirrups. In cases of suspected trauma or abuse, a foreign body in the vagina, or other suspected structural abnormalities, knee-chest position can be used in a child older than 2 years of age (Figure 17-8). Have the child rest her chest on the exam table and support her weight on bent knees, which are positioned 6 to 8 inches apart. Her buttocks will be held up in the air and her back and abdomen will fall downward. In this position, using a penlight or an otoscope head for magnification and light, the examiner can visualize the lower vagina, and in prepubertal girls often the upper vagina. Lateral separation of the labia will be required to visualize the hymen (Figure 17-9). FIGURE 17-7 Frog-leg positioning. (From McCann JJ, Kerns DL: The anatomy of child and adolescent sexual abuse: a CD-ROM atlas/reference, St. Louis, 1999, Intercorp Inc.)

Female genitalia

Embryological development

Developmental and physiological variations

Condition

Description

Ambiguous genitalia

Partially fused labia, enlarged clitoris; hypospadias, bilateral cryptorchidism in an apparent male are signs of a possible intersex condition (see Chapter 15)

Hydrocolpos

Vaginal secretions collecting behind an imperforate hymen at birth may appear as small cystic mass between labia

Vaginal agenesis

Congenital absence of or hypoplasia of fallopian tubes, uterine corpus, uterine cervix, and proximal portion of vagina; occurring in approximately 1 in 5000 births; in approximately 10% of these births, there is a rudimentary or functional uterus

Commonly diagnosed at puberty when child presents with primary amenorrhea; however, can be recognized at birth; should be diagnosed before onset of puberty

Anatomy and physiology

Sexual Maturity Rating (SMR)/Tanner Stage

Pubic Hair Development

Genital Changes Due to Estrogenization*

1

No growth of pubic hair

Thicker, more elastic labia minora and hymen, change from columnar (red) to squamous (pink) epithelium in vagina (SMR 1-2)

2

Downy, scarcely pigmented straight hair, especially along medial border of labia majora

Physiological leukorrhea (SMR 2-3)

3

Sparse, visibly pigmented curly (coarse and straight in Asian and American Indian girls) pubic hair on labia

Physiological leukorrhea (SMR 2-3)

Onset of menses (SMR 3-4)

4

Hair coarse, curly (coarse and straight in Asian and Native American girls), abundant, but less so than adult; no extension onto medial thighs

Onset of menses (SMR 3-4)

5

Lateral spreading, triangle distribution with some spread onto medial thighs

Vaginal Changes

Prepubertal Girls

Pubertal Adolescents

Vaginal pH

6.5-7.5 (alkaline)

<4.5

Vaginal mucosa

Columnar epithelium (red)

Stratified squamous epithelium (pink); presence of columnar epithelium on ectocervix, surrounding the os

Vaginal mucous glands, discharge

Absent

Present; physiological leukorrhea usually begins at SMR 2-3

Normal vaginal flora

Gram-positive cocci and anaerobic gram-negative bacteria; gonorrhea and chlamydia focally infect vagina

Lactobacilli; yeast part of normal flora; gonorrhea and chlamydia commonly infect cervix

Vaginal length

4-5 cm

11-12 cm

External genitalia

Thin labia, rigid, nonelastic, thin-walled vagina

Thicker labia; thicker, more elastic, wavy, or redundant hymen; more elastic vagina

Family, cultural, racial, and ethnic considerations

System-specific history

Age-Group

Questions to Ask

Preadolescent and adolescent

Menstrual history: Age at menarche, regularity of cycles, any spotting or bleeding between cycles, dysmenorrhea, family history of menstrual problems?

For primary amenorrhea: Age of thelarche and adrenarche, presence or absence of secondary sex characteristics?

For secondary amenorrhea: Any weight loss attempts, including restriction, binging, purging? Significant physical or emotional stress?

Adolescent

Sexual history: Any prior sexual activity, including number and gender of partners, types of activity, use of contraception and/or barrier protection?

Coerced or unwanted sexual activity?

History of prior examinations, prior infections?

Use of over-the-counter medications and cosmetic products or douches? Shaving, waxing or use of depilatories for pubic and thigh hair?

Physical assessment

Examination of prepubertal girls

Positioning

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Female genitalia

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue