Fecal Incontinence and Constipation

Most patients who require repair of an ARM suffer from some degree of a functional defecation disorder. All have some degree of an abnormality in their fecal continence mechanisms. One-quarter of them are deficient enough to the point that they are fecally incontinent and cannot have a voluntary bowel movement.1 The majority are capable of having voluntary bowel movements but may require treatment of an underlying dysmotility disorder, which most often manifests as constipation.2,3 A small, yet significant, number of patients with Hirschsprung disease suffer from fecal incontinence because of a lost anal canal or damaged sphincters that occurred during operative repair.4–6 To varying degrees, patients with spinal problems7,8 or injuries9 can lack the capacity for voluntary bowel movements.

Patients with true fecal incontinence require artificial means to be kept clean. This regimen is termed bowel management and involves a daily enema.10 On the other hand, patients with pseudoincontinence require proper medical treatment for either constipation or loose stools. This involves finding the right consistency for the stool so that they can have a bowel movement that they voluntarily control. Understanding this major differentiation is the key to deciding the correct bowel management program.

Mechanism of Continence

Fecal continence depends on three factors: voluntary sphincter muscles, anal canal sensation, and colonic motility.2

Anal Canal Sensation

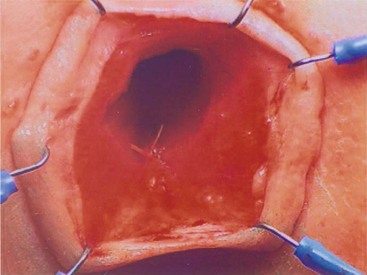

Exquisite sensation in normal individuals resides in the anal canal. Except for patients with rectal atresia, most patients with ARMs are born without an anal canal. Therefore, sensation does not exist or is rudimentary. Patients with spinal conditions may lack this anal canal sensation as well.7,8 Those with Hirschsprung disease are born with a normal anal canal, but this can be injured if not meticulously preserved at the time of their pull-through (Fig. 36-1).5,6 Also, perineal trauma may result in an injured or destroyed anal canal.9

FIGURE 36-1 Loss of the anal canal (with no visible dentate line) is seen after a Soave pull-through operation. In this patient, the anal dissection was begun too distally.

It seems that most individuals can perceive distention of the rectum. This point is important for patients undergoing pull-through procedures for imperforate anus as the distal rectum and anus must be placed precisely within the sphincter mechanism. This sensation seems to be a consequence of stretching of the voluntary muscles (proprioception). The most important clinical implication of this point is that patients might not feel liquid or soft fecal material because such stool consistency does not distend the rectum. Thus, to achieve some degree of sensation and bowel control, the patient must have the capacity to form solid stool. This is especially important in a patient without a good anal canal to give sensory cues. This point is relevant in children with ulcerative colitis who have undergone an ileoanal pull-through procedure. They can suffer from varying degrees of incontinence due to their incapacity to form solid stool, but their normal sphincter muscles and anal canal allow them to overcome this problem. Most need treatments that bulk up the stool.

Bowel Motility

Most patients with an ARM suffer from some disturbance of this sophisticated bowel motility mechanism. Patients who have undergone a posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) or any perineal approach in which the most distal part of the bowel was preserved can develop an overefficient bowel reservoir (megarectosigmoid) (Fig. 36-2). The main clinical manifestation is constipation, which seems to be more severe in patients with lower defects.3 Constipation that is not aggressively treated, combined with an ectatic distended colon, eventually leads to more severe constipation. A vicious cycle ensues, with worsening constipation leading to more rectosigmoid dilation, leading to more severe constipation, and then to overflow incontinence.

FIGURE 36-2 This contrast enema shows a megarectosigmoid colon. (From Peña A, Levitt M. Colonic inertia disorders in pediatrics. Curr Prob Surg 2002;39:681.)

Patients with an ARM, who are managed with operations in which the most distal part of the bowel was resected (Fig. 36-3), behave clinically as individuals without a rectal reservoir. Depending on the amount of colon removed, the patient may have loose stools. In these cases, medical management consists of enemas, a constipating diet, and medications to slow down the colonic motility. Patients with Hirschsprung disease undergo operative resection of the distal aganglionic colon and rectum. However, their normal anal canal and sphincter mechanism (if properly preserved) allows the vast majority of them to be continent despite the lack of a rectal reservoir. Some patients with Hirschsprung disease have bowel hypermotility and need medications to slow the colon. Amazingly, some patients with an injured anal canal can be continent if their motility is normal because the regular contraction of the rectosigmoid can translate into a successful voluntary bowel movement.

FIGURE 36-3 This contrast enema was performed in a patient who had resection of the rectosigmoid colon. Often these patients act like they do not have a rectal reservoir. (From Levitt MA, Peña A. Treatment of chronic constipation and resection of the inert rectosigmoid. In: Anorectal Malformations in Children. Heidelberg: Springer; 2006. p. 417.)

True Fecal Incontinence

True fecal incontinence means the patient cannot have voluntary bowel movements and therefore requires an artificial mechanism to empty the colon. We have found that the ideal approach is a bowel management program consisting of teaching the patient and the parents how to clean the colon once daily with an enema so they stay completely clean for 24 hours until the next enema. This is achieved by keeping the colon quiet between enemas. Laxatives will make such a patient soil more. The program, although simplistic, is ideally implemented by trial and error over a period of one week.10 The patient is seen each day and an abdominal radiograph is obtained to look for the amount and location of any stool left in the colon. The presence or absence of stool in the underwear is also noted. The decision as to whether the type and/or quality of the enemas should be modified, as well as any changes in diet and/or medication, is made each day (Fig. 36-4).10

FIGURE 36-4 (A,B) This series of abdominal radiographs was obtained during inpatient bowel management showing progression toward a completely clean colon with daily adjustment of the enema. (C) After five days, a postcontrast abdominal film shows minimal evidence of retained fecal material.

Which Children Have True Fecal Incontinence?

In children with ARMs, 75% who have undergone a correct and successful operation have voluntary bowel movements after the age of 3 years.1 About half of these patients occasionally soil their underwear. These episodes of soiling are usually related to constipation. When the constipation is treated properly, the soiling frequently disappears. Thus, approximately 40% overall have voluntary bowel movements and no soiling, and behave normally. Children with good bowel control still may suffer from temporary episodes of fecal incontinence, especially when they experience diarrhea.

Some 25% of all patients with ARMs suffer from true fecal incontinence, and are the patients who need bowel management to be kept clean. As previously noted, certain patients with Hirschsprung disease and those with spinal problems can suffer from true fecal incontinence as well. For these patients, similar principles of bowel management learned from treatment of patients with ARMs can be applied.10

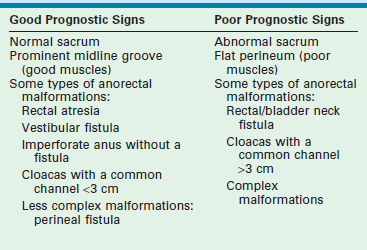

For children with ARMs, the surgeon should be able to predict in advance which patient will likely have a good functional prognosis and which child will have a poor prognosis. Table 36-1 shows the most common indicators for a good or poor prognosis. After primary repair and colostomy closure, it is possible to establish a functional prognosis (Table 36-2). Parents should be given the information regarding their child’s realistic chances for bowel control to avoid needless frustration at the age of toilet training.

TABLE 36-1

Prognostic Signs in Patients with Anorectal Malformations

| Good Prognosis Signs | Poor Prognosis Signs |

| Good bowel movement patterns: one to two bowel movements per day, no soiling in between | Constant soiling and passing of stool |

| Evidence of sensation with passing stool (pushing, making faces) | No sensation (no pushing) |

| Urinary control | Urinary incontinence, dribbling of urine |

Once the diagnosis of the specific anorectal defect is established, the functional prognosis can be predicted. If the child’s defect is associated with a good prognosis such as a vestibular fistula, perineal fistula, rectal atresia, rectourethral bulbar fistula, or imperforate anus with no fistula, one should expect that the child will have voluntary bowel movements by the age of 3 years provided the sacrum and spine are normal. These children will need careful attention to avoid fecal impaction, constipation, and soiling.3

In patients who have undergone repair of an imperforate anus and who have fecal incontinence, reoperation to relocate a misplaced rectum or repair a rectal prolapse should be considered if the child was born with a good sacrum, a good sphincter mechanism, and a malformation with good functional prognosis. A repeat PSARP can be performed and the rectum relocated within the sphincter mechanism.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree