Family and Community Violence

Renée Boynton-Jarrett and Robert Sege

Violence is among the leading causes of death and disability for American children and adolescents. The epidemic of murder took the lives of approximately 2000 young people annually between 1980 and 2002. During this period, approximately 1 of every 4 youth homicides was committed by juveniles. Overall, homicide was the third leading cause of death for youth aged 13 to 21 and the leading cause of death for African American young men in this age category. Despite a recent national decline in the homicide rate, the United States continues to have one of the highest homicide rates in the world.1,2

While homicide is the most extreme form of community violence, many more young people are injured: The ratio of nonfatal to fatal assaults is estimated to be 100 to 1. Over 780,000 youth were treated in US emergency departments for nonfatal injuries in 2004, and twice as many are victims of physical dating violence each year. When surveyed, over one third of high school students report having been in a physical fight in the past 12 months (40% and 25% of males and females respectively); in fact, the rate of injuries due to fighting has remained steady for decades. One in 8 youths reported carrying weapons for protection, and 1 in 9 report avoiding school due to fear of violence.3

The quality of the family and community environment during childhood and adolescence has profound and lasting effects, which persist into adulthood. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to violence is among the earliest and most pervasive adverse experiences.4 Childhood adversities have been linked to future physical, mental, and developmental health and to all major causes of morbidity and mortality in adulthood.5,6 One of every 10 children attending a Boston, Massachusetts, city hospital pediatric primary care clinic witnessed a shooting or stabbing in their homes or communities before the age of 6.7 This high prevalence of violence exposure underscores the importance of violence as a public health problem.

Pediatricians play a crucial role in preventing, identifying, and intervening in such situations. Contrary to the perception that violence consists of random acts in society, violence is most likely to be perpetrated by individuals known to the victim. Hospital readmission for subsequent assaults and homicide are high. Moreover, violence is associated with known risk and resilience factors that may be routinely assessed during the course of medical care.8

Well-established risk factors for violence-related injury include access to firearms, history of fighting or injury, violent discipline, alcohol and drug use, exposure to familial violence, media violence, and gang involvement. As this list of risk factors makes evident, distinct forms of violence rarely occur in isolation. In addition to these individual risk factors, violence also tends to be highly correlated with other social adversities, particularly poverty, substance abuse, housing insecurity, parental mental health challenges, and neighborhood disadvantage.9

The accumulation of violence exposure and other social risks may overwhelm a young person’s ability to cope with adversities effectively.10 Indeed, the adverse effects of exposure to violence on mental, physical, and developmental health are often cumulative.11

This chapter reviews the epidemiology, health, and developmental impact of familial, dating, and community violence and violence exposure. The intent is to provide an overview of the pattern of violence exposure among youth in the United States and useful approaches to prevention, identification, and intervention for pediatricians in the clinical setting.

FAMILY VIOLENCE

Family violence refers to acts of violence between family members. While all forms of family violence may have grave consequences, this section highlights intimate partner and sibling violence. Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes the actual or threatened emotional, physical, psychological, or sexual abuse between 2 individuals in a close (ie, current or former dating/marital) relationship. Although IPV is present in relationships across class, culture, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation, this phenomenon is characterized by a gender disparity; in 2001, the US Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that 85% of victims of IPV are women. Between 3 and 10 million children are exposed to IPV annually. The risk of child maltreatment increases as the level of violence in the household increases: Children exposed to IPV are 6 to 15 times more likely to be abused. Children who witness IPV in their homes are at an increased risk of violence in future intimate relationships. Parental history of abuse in childhood, substance abuse, and poor mental health increases the likelihood of family violence. Although IPV spans the socioeconomic gradient, poorer children may be at higher risk of exposure.9

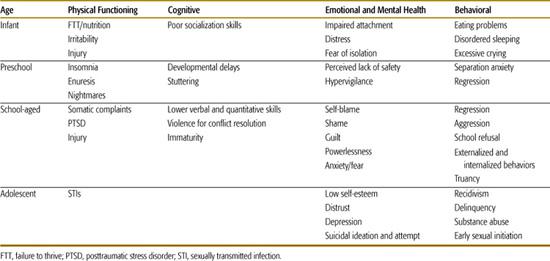

The impact of intimate partner violence on child health, behavior, cognitive development, and academic performance may vary by age and developmental stage (see Table 36-1). An expansive body of research has documented an association between toxic family environments and mental health problems, including externalizing symptoms such as aggression, conduct disorder, and antisocial behavior, and internalizing symptoms such as anxiety disorders, depression, and suicidal behavior.12 Moreover, the association between childhood adversities, such as IPV exposure and household dysfunction, with subsequent poor physical health is well-established.9,10,13 Youth residing in environments characterized by aggression, conflict, and neglect are more likely to exhibit health-threatening behaviors (eg, smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, and risky sexual practices). Violence exposure may impact development of strategies to process emotions and coping responses and ultimately lead to higher emotional reactivity. Social competence—social skills, cognition, and prosocial behaviors—may be impacted by deficits in the ability to temper emotions and by lack of role modeling and socialization in the home. Not surprisingly, adaptation to school, academic performance, and peer relations may be subsequently influenced.

When the family environment is a source of threat as well as protection, the parental role as physicaler emotional reactivity. Social and emotional caregiver can be severely compromised. Parent-child relationships may be strained by caregiver depression, emotional unavailability, feelings of helplessness to protect the child, and social stress associated with battering. Therefore, the parental response to violence may compound the child’s vulnerability in the context of violence exposure. Witnessing a life-threatening act against a caregiver is ranked among the most traumatic experiences a child can face and may lead to posttraumatic stress disorder or associated symptoms.7,12,14

SIBLING VIOLENCE

SIBLING VIOLENCE

Sibling violence is commonly discounted as more benign and less harmful than other forms of peer violence. Approximately 35% to 50% of children report being hit or attacked by a sibling annually.15 Overall, sibling violence tends to result in fewer serious injuries than peer violence and involves the use of fewer potentially injurious weapons; however, sibling violence is more likely to be chronic and therefore may hold greater potential for trauma symptoms. Sibling violence may vary depending on the age of the perpetrator; for example, impulsivity and inability to foresee consequences may imbue child aggressors with the greatest potential to cause harm.16

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

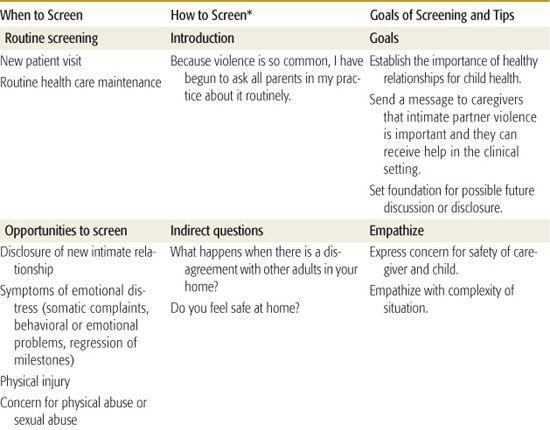

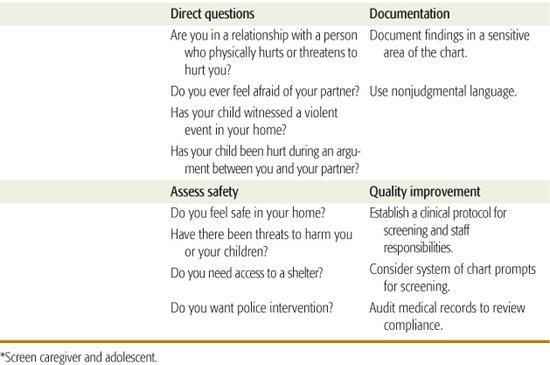

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association recommend incorporating screening for Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) into routine health care maintenance. Screening should take place during new patient visits, annual well-child visits, if a new intimate relationship is disclosed, or if concerning symptoms arise. Symptoms of emotional distress, including somatic complaints and behavioral and emotional problems, or an obvious physical injury should prompt screening for family violence. Among younger children, regression from established milestones for language, communication, and bowel and bladder control should raise concern for the possibility of family violence. Details on whom, when, and how to screen are summarized in Table 36-2.

Table 36-1. Potential Effects of Witnessing Family Violence by Age and Developmental Stage

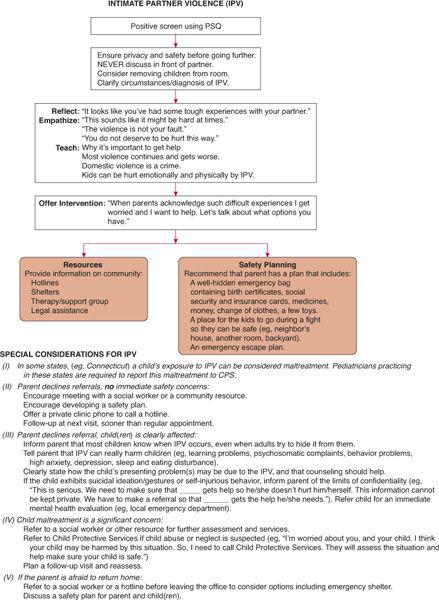

An approach to management following disclosure of IPV is provided in Figure 36-1. Safety planning may be complex and time consuming; many physicians refer affected caregivers to a social worker or advocate. Clinicians can establish a clinical protocol for IPV screening, assessment, anticipatory guidance, and response if familial violence is identified. Establishment of a multi-disciplinary team or collaboration with community agencies may enhance clinical training and resources available for patient care.

Children may benefit from referral to comprehensive mental health services or to specific programs that provide trauma-informed care and allow parent and child to communicate about violent episodes safely. Referrals are particularly warranted in the setting of behavioral change, symptoms persisting longer than 3 months, witnessing severe violence, or an emotionally unavailable caregiver. In those cases in which a report to the state child protective services is warranted, the report should include information regarding the presence of IPV, and the response of child protective services should be designed in a way to promote safety for both adult and child victims.

The acceptability of screening for IPV in the pediatric setting is high and is associated with improved parental satisfaction.17,18 Many abused parents will not seek medical care for themselves but will seek care for their children, further supporting the inclusion of IPV screening in routine care.

Parents and youth should be screened routinely regarding the nature and pattern of sibling disagreements. Screening provides a valuable opportunity for prevention and early identification. The introduction of alternative forms of conflict resolution is important. Sibling violence resulting in injuries or trauma symptoms should be referred to mental health specialists, family counselors, or family crisis intervention. Serious intentional injuries or threats and repeat injuries should be referred or reported to appropriate services.

DATING VIOLENCE

Teen dating violence may represent a bridge between exposure to family violence in childhood and violent adult intimate relationships. Patterns of intimacy are established during adolescence. Unfortunately, approximately 10% to 25% of adolescents report experiencing physical and/or sexual dating violence.19

Dating violence includes physical, sexual, verbal, and emotional violence. Although both young men and young women inflict and receive physical abuse, females are more likely to experience severe physical and sexual violence; they are 3 to 6 times more likely to experience dating violence than males. The lifetime prevalence of dating violence is 1 in 5 among adolescent girls. In fact, 10% of intentional injuries experienced by adolescent females are perpetrated by dating partners.20 Dating violence is associated with risky health behaviors, including earlier sexual debut, a greater number of sexual partners, inconsistent condom use, and alcohol and drug use.21 Youth exposed to dating violence are more likely to have sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy during adolescence, and a history of social adversities, including exposure to family and community violence.22

Youth in same-sex relationships are at a particularly elevated risk of violence in intimate relationships. Among young men, the number of same-sex male partners correlated with higher frequency of dating violence.23 Vulnerability to violence may be linked to social isolation; moreover, concerns for social acceptance may increase challenges to seeking care.

Pregnant teens also experience a sharply elevated risk of violence in intimate relationships. An estimated 7% to 26% of adolescent females report violence during pregnancy inflicted by a partner or family member. Unfortunately, violence during pregnancy predicts continuing violence: 75% of teens who report exposure to violence during pregnancy also report violence 2 years postpartum.24,25

There is consistent evidence that both the perpetrators and victims of youth dating violence are at an elevated risk of serious health concerns, including suicidal ideation, lower health-related quality of life, risky sexual behaviors, illicit drug use, antisocial behaviors, disordered eating, and unhealthy weight control behaviors. Greater awareness of the multiple health risks associated with dating violence may elevate the index of suspicion and lead to more timely identification and intervention.

Table 36-2. Intimate Partner Violence: When, Who, and How to Screen

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Pediatricians should routinely screen for both victims and perpetrators of dating violence. Screening should occur during visits for annual health maintenance, family planning, emergency contraception, and following disclosure of a new intimate relationship. Recommended screening questions are included in Table 36-3. Special attention should be paid to pregnant and postpartum teens who should be screened repeatedly. Additionally, young people with a history of school failure, multiple pregnancies, repeat sexually transmitted infections, and multiple requests for emergency contraception may be particularly vulnerable to dating violence. A climate that avoids assumptions of a heterosexual orientation will allow for an open dialog on intimate relationships with all teens.

Pediatricians should routinely provide anticipatory guidance on the characteristics of healthy relationships and strategies for resolving conflicts. Providers should assess the safety of youth who reveal dating violence, seek support from mental health specialists, and refer patients and their parents to community-based youth development and asset-building programs. As discussed later in this chapter, resources related specifically to the prevention of dating violence are available to clinicians from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

COMMUNITY VIOLENCE

In modern society, youth are at heightened risk of being victims of, witnessing, and hearing about violence or knowing a relative or peer who died violently. In comparison to suburban youth, youth residing in urban areas report higher rates of witnessing severe violence—stabbings and shootings—while youth in rural areas report high rates of witnessing threats, psychological abuse, and beatings by peers.12,14

Minority youth are at particularly high risk of exposure to community violence. Racial/ethnic disparities in the homicide rate exist, and African American young men are at greater risk of homicide; between ages 18 and 24 years, they are 8 times more likely than their white counterparts to be murdered. In addition, all children, regardless of race, are at high risk of violence-related injury. The risk of being killed at home increases dramatically whenever there is a handgun in the home. Alcohol and drug use are associated with violent events and injury.

Witnessing violence has been associated with psychological, social, academic, cognitive, and physical challenges as well as with propensity to engage in violent acts in the future. Young persons in violent communities have a higher likelihood of weapon-carrying and aggression. Although exposure to firearm violence has been associated with a heightened risk for perpetration of serious violence, the majority of youth exposed to violence do not perpetrate abuse or engage in criminal behavior. Moreover, youth are less likely to carry concealed firearms if they reside in neighborhoods that are safe, have greater social and physical order, and have higher collective efficacy—social cohesion and informal social control.

Exposure to community violence influences perceptions of safety and security, which may undermine development of trust and autonomy and thereby hinder efforts to obtain mastery of the social environment. Somatic symptoms, anxiety, depressive symptoms, irritability, sleep disturbances, and posttraumatic stress disorder and associated symptoms result from acute or chronic exposure to community violence. Approximately one third of urban youth exposed to community violence meet criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder, and nearly two thirds of adolescent girls exposed to community violence have the symptomatology.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree