Chronic pelvic pain is common among women of reproductive age and is associated with significant morbidity and comorbidities. In this Viewpoint, we explore the evolutionary cause of pelvic pain and summarize evidence that supports a menstruation-related evolutionary cause of chronic visceral pelvic pain: (1) lifetime menstruation has increased; (2) severe dysmenorrhea is common in the chronic pelvic pain population, particularly among those with pain sensitization; and (3) a potential biological mechanism can be identified. Thus, chronic pelvic pain may arise from the mismatch between the slow pace of biological evolution in our bodies and the relatively rapid pace of cultural changes that have resulted in increased menstrual frequency due to earlier menarche, later mortality, and lower fecundity. One possible mechanism that explains the development of persistent pain from repeated episodes of intermittent pain is hyperalgesic priming, a physiological process defined as a long-lasting latent hyperresponsiveness of nociceptors to inflammatory mediators after an inflammatory or neuropathic insult. The repetitive severely painful menstrual episodes may play such a role. From an evolutionary perspective the relatively rapid increase in lifetime menstruation experience in contemporary society may contribute to a mismatch between lifetime menstruation and the physiological pain processes, leading to a maladaptive state of chronic visceral pelvic pain. Our current physiology does not conform to current human needs.

Introduction

Chronic pelvic pain remains a major health problem for many women and a socioeconomic burden for societies. The problem of chronic persistent pain remains in spite of helpful medical approaches and surgical interventions. In this Viewpoint, we explore evidence that may support an evolutionary cause for development of some aspects of chronic visceral pelvic pain.

Evolutionary medicine is made up of the intersections where “evolutionary insights bring something new and useful to the medical profession, and where medical research offers new insights, questions, and research opportunities for evolutionary biology.” Human beings and other organisms are molded by natural selection to maximize reproduction, not health, an imperative that causes unavoidable trade-offs. Disease can arise from the mismatch between our bodies and modern environments, given the slow pace of biological evolution and the relatively rapid pace of cultural change. Evolutionary theory indicates a need to study both proximal and evolutionary explanations of a disease. The former is associated with the physiological and pathological processes defining how the disorder affects individuals while the latter is directed to the definition of why the condition occurs. The proximal explanations of chronic pelvic pain are vast in number but include the presence of endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, and interstitial cystitis. Until now there has not been an evolutionary explanation identified to explain this common problem.

Changes in human physiology may happen more rapidly that the processes of adaptation. The theoretical basis for why illnesses occur may be seen as a mismatch between our current human environment and selected traits. Evolutionary biology has been used to understand inflammatory disease among other conditions. We explore the strengths and weaknesses of the dramatic changes in the lifetime frequency of menstruation with the maladaptive state of chronic pelvic pain.

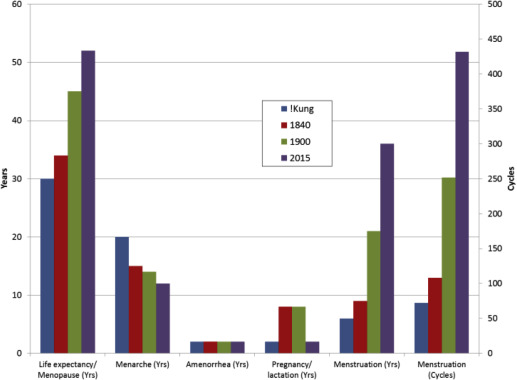

In 1976 Roger Short made the observation that in contemporary society, women are having many more menstrual cycles than the native !Kung hunter gatherer population and many more than women prior to the development of contraception. An evolutionary view supporting the role of increased menstrual frequency in the development of chronic visceral pelvic pain could be considered if: (1) lifetime menstruation has increased; (2) severe dysmenorrhea is common in the chronic pelvic pain population, particularly among those with pain sensitization; and (3) a potential biological mechanism can be identified.

Lifetime exposure to menstruation has increased

Lifetime menstruation is a function of many factors including age at menarche, mortality, menopause, frequency of pregnancy and lactation, and presence of amenorrhea. There has been a dramatic nearly linear decrease in the age of menarche since 1860 when it was reported to occur at age 17 years. The changes in the age of menarche have been attributed to improved nutrition permitting increased fat availability. Based on the linearity of the data, it is possible that menarche may have occurred even >17 years among our ancestors due to nutritional limitations.

Similarly, there has been a significant increase in life expectancy, from 40 years in 1860 to 86-90 years in 2010 in Western counties. Again, the linearity of the data may permit the projection that average mortality rates may have been much lower in our ancestors. For example, it is estimated that !Kung hunter gatherers have a life expectancy between 24-35 years.

The average age of menopause historically is uncertain possibly due to earlier rates of mortality but has been noted currently to be approximately 52 years. The age of menopause has been noted to possibly be earlier among aboriginal communities.

Pregnancy was much more common prior to effective contraception. Canadian and US population studies indicate the average number of births was 7-8 per family in the 19th century. Limited lifetime menstrual function is supported from studies of pre-Civil War populations in New York in 1840. Pregnancies were likely followed with lactational amenorrhea. There are no available data that would contribute additional amenorrhea due to spontaneous abortion. Short has indicated there would have been episodes of amenorrhea due to immaturity of the reproductive system in adolescence and perimenopause and has further provided estimates of reproductive function of the Hutterite population.

The available information regarding the factors associated with menstruation is presented in the Figure . Contemporary estimates are based on menarche at age 12 years, average family size of 2 pregnancies, 1 year of lactation, menopause at age 52 years (in lieu of mortality rate), and 2 years of physiological amenorrhea. Data from 1840 use pre-Civil War information: menarche at age 17 years, 8 pregnancies and lactation, 2 years of physiological amenorrhea, and mortality at 40 years of age. Life expectancy of the !Kung hunter gatherers was estimated previously by Pennington.

Lifetime exposure to menstruation has increased

Lifetime menstruation is a function of many factors including age at menarche, mortality, menopause, frequency of pregnancy and lactation, and presence of amenorrhea. There has been a dramatic nearly linear decrease in the age of menarche since 1860 when it was reported to occur at age 17 years. The changes in the age of menarche have been attributed to improved nutrition permitting increased fat availability. Based on the linearity of the data, it is possible that menarche may have occurred even >17 years among our ancestors due to nutritional limitations.

Similarly, there has been a significant increase in life expectancy, from 40 years in 1860 to 86-90 years in 2010 in Western counties. Again, the linearity of the data may permit the projection that average mortality rates may have been much lower in our ancestors. For example, it is estimated that !Kung hunter gatherers have a life expectancy between 24-35 years.

The average age of menopause historically is uncertain possibly due to earlier rates of mortality but has been noted currently to be approximately 52 years. The age of menopause has been noted to possibly be earlier among aboriginal communities.

Pregnancy was much more common prior to effective contraception. Canadian and US population studies indicate the average number of births was 7-8 per family in the 19th century. Limited lifetime menstrual function is supported from studies of pre-Civil War populations in New York in 1840. Pregnancies were likely followed with lactational amenorrhea. There are no available data that would contribute additional amenorrhea due to spontaneous abortion. Short has indicated there would have been episodes of amenorrhea due to immaturity of the reproductive system in adolescence and perimenopause and has further provided estimates of reproductive function of the Hutterite population.

The available information regarding the factors associated with menstruation is presented in the Figure . Contemporary estimates are based on menarche at age 12 years, average family size of 2 pregnancies, 1 year of lactation, menopause at age 52 years (in lieu of mortality rate), and 2 years of physiological amenorrhea. Data from 1840 use pre-Civil War information: menarche at age 17 years, 8 pregnancies and lactation, 2 years of physiological amenorrhea, and mortality at 40 years of age. Life expectancy of the !Kung hunter gatherers was estimated previously by Pennington.